- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

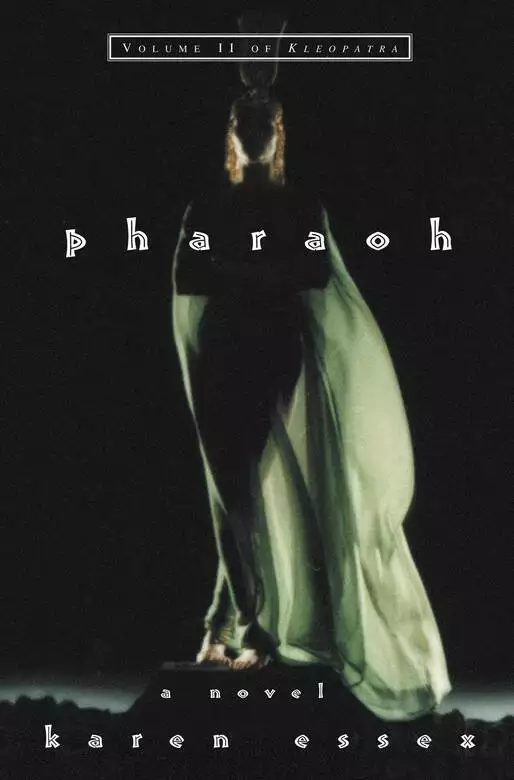

Synopsis

Following on from Kleopatra, the glittering epic of Egypt's queen continues as she allies herself with Anthony and begins a love story that immortalizes her as one of history's greatest political players and most tragic heroines.

Release date: May 30, 2009

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

PHARAOH - VOLUME II

Karen Essex

tense, confused, they await her inspection and her command.

Charmion, the weary sergeant, the old warhorse long attached to an unpredictable commander in chief, has herded them to Kleopatra’s

chambers in utter silence. A great feat of intimidation, the silencing of a gaggle of whores. But that is the way with Charmion,

who executes every duty with a diligence unanimat-ed by emotion of any kind. She retains an implacable expression even while

carrying out the bizarre wishes of the sovereign to whom she has sworn her life. An aristocratic Greek born in Alexandria,

Charmion is not tall, but casts the illusion of towering height. Her bearing shames the carriage of a queen, even of the queen

she serves. Though she is fifty-one, her sallow skin is smooth. Three wrinkles, delicate as insects’ legs, trace from the

corners of her brown-yellow eyes. Her mouth is full, a burnt color, like a river at sundown. Two tributaries, both southbound,

run from her lip-locked smile, tiny signals of age, a result of the anxiety she suffers over the queen’s behavior.

Unlike the queen, Charmion dislikes all men. Wordlessly, she has endured Kleopatra’s relations with Antony with lugubrious

countenance, as if she has suffered all these years from an intense constipation. Antony, charmer of maidens, actresses, farm

girls, and queens, never elicits a smile from the woman. In her youth, the queen heard, Charmion had bedded with other women,

though she

could never confirm the rumors. Of Caesar, and of the queens relations with him, however, she had approved, though her sanction

was expressed only by absence of criticism.

Charmion has dressed the prostitutes herself, forcing Iras, the temperamental eunuch, Royal Hairdresser to the queen, to weave

tiny jewels and trinkets of gold into their locks. For a prim woman, she possesses a talent for seductive costume. Knowing

the Imperator’s inclinations, she has chosen many large-breasted girls. On the most obscenely endowed, she has encased their

sumptuous glands in loosely woven gold mesh so that the nipples, rouged to an incarnadine red, appear trapped in an elegant

prison, eager for release. “Antony shall enjoy that,” thinks the queen.

The courtesans regard their monarch, wondering what kind of queen, what kind of woman, sends prostitutes to her husband, much

less approves their comeliness before she allows them to go to him. The queen, nervous, reading their thoughts, attempts to

cover her trepidation with characteristic chilling authority. She rises to scrutinize her troops who are wrapped not with

the armor of war, but with the luxurious weaponry of seduction. Reddened lips, slightly parted. Little invitations. Nipples:

crimson, erect, acute, like hibiscus buds against stark white skin. Bare, nubile shoulders soft as dunes. Teasing one, an

auburn tendril; grazing another, a crystal earring, sharp as a dagger, threatening to stab the perfect flesh. Luminous, kohl-rimmed

eyes; vacant eyes, eyes without questions. Eyes that do not accuse, do not interrogate. Eyes that know how to lie. A naked

belly and then another, larger, stronger, with a garnet chunk-or is that a ruby?-tucked in the navel. And of course, the prize-the

female motherlode, coy, apparent, beneath transparent gauze. Some shaven, some not. Good work, Charmion, she thinks. Like

all men, her husband craves variety.

A detail: long fingers, slender toes, adorned with rings, jewels. Excellent. Ah, but not this one. “She must leave,” the queen

says sharply, not to the half-breed beauty before her with fat, choppy hands, but to Charmion, who waves the girl out of the

room. Antony, connoisseur of the female form, dislikes “peasant digits.”

“Have we more?” she demands of her lady-in-waiting, knowing how thoroughly prepared she is for any situation, any disaster.

“Yes, Your Royal Grace. There are twelve alternates in the antechamber.”

“Bring me two thin girls. Boyish. Young, please. Two waif-faced pretties without inhibition.”

With a nod, Charmion leaves the room, returning with twin girls of thirteen, draped in the simple robes of a Greek boy, with

one small breast peeking from the

fold. The androgynous creatures curtsy low, remaining on the ground until the queen passes them, rising only at the snap of

Charmion's fingers. Compliant in nature, schooled in ritual. That should please her husband. A fine mix.

“Yes, I believe we are complete now. Twelve in all.

“Ladies,“she says in her most imperious voice. They stand at attention, but only Sidonia, the voluptuous red-headed madam

of the courtesans, meets her gaze. “Marcus Antonius, my husband, my lord, proconsul of Rome, commander of the armies of the

eastern empire, sits alone, inconsolable, gazing over the sea. He is despondent.

“I do not explain myself to the highest ministers in my government, much less to court prostitutes. But you, ladies, are the

foot soldiers in my campaign. No longer are you mere vessels of pleasure, actresses in the erotic arts, receptacles of spilt

semen. Today you are elevated. Sacred is your cause, urgent your mission. At stake is the Fate of Egypt, and your Fate and

my Fate. At stake is no less than the world.”

Now the ranks stare at her in disbelief, for what queen makes an army of whores? Puts the Fate of her kingdom in the hands

of a dispatch of painted strumpets?

“You must revive my husband. It is as simple as that.”

One of the girls, the one with the tough stomach and bejeweled navel, struggles to stifle a giggle, but Sidonia sees the stern

raised eyebrow of Charmion arched in warning. She slaps the girl, who crumples to the ground in tears. Sidonia bows apologetically

to the queen, kicking the girl with a sandaled foot, reducing her cries to a choked dog-whimper

The queen is amused but remains nonplussed-a countenance at which she excels, thanks to her apprenticeship with the late Julius

Caesar. “Tonight, ladies, you serve one of the greatest men in history. His courage is legend. His conquests span the world.

His loyalty, his heroism, unparalleled. But he sulks alone in his mansion by the sea. The mighty lion cringes and licks his

wounds. He must rally. He must become a man again. And we know, ladies, don’t we, what makes a man a man?”

Every whore smiles. For all their differences-the queen of Egypt and courtesan slaves-they share the same intuitive knowledge.

What every woman knows. What every woman uses.

“I am aware that there is gossip. And I am aware of those who spread it. They will be dealt with. As for you, you are to let

all those who visit your chambers know that your queen sailed home into the harbor of Alexandria flying the flagsof victory after the war in Greek waters. You are to say that the Imperator, my husband, is your most virile and demanding

client, that you have heard with your own ears and seen with your own eyes his plans for victory against Octavian, the fiend

who will terrorize our world if his ambitions are allowed to go unchecked. As you know, I do not allow soldiers to have their

way with court prostitutes, politically convenient as it would be at times. The Roman army, should it descend upon our city,

will not follow these rules. I encourage each of you to meditate on the Roman reputation for cruelty and degradation to conquered

women and then imagine your Fates, ladies, in the event that the Imperator does not overcome his depressed condition and refuses

to defend you against the Romans.

“Therefore, you shall succeed splendidly in rehabilitating the manhood of my husband and you shall spread with conviction

to every man, minister, artisan, and soldier alike who enters your bed that the great Antony fights a war the way he makes

love-with vigor, with passion. That his prowess in the sport of war is excelled only by his prowess in the sport of love.

Let the word spread to all corners of the city, and let it be heard by sailors who will take the tales to other ports. I know

you have the power to convince. I requested not only the most beautiful of you for this mission, but the most intelligent.

The most shrewd.

“As you are cunning, I shall make you a bargain. If you do your job to perfection, you shall be given your freedom after Octavian

is defeated. If you fail and my husband remains in his tower sulking like a baby, you shall be put into the fields to harvest

the crops, or sent to the Nubian mines. Let me be plain: If you betray the throne, if you are heard uttering one word about

the Imperator’s melancholia, if rumors of his ill-humor are traced back to you, if you do not follow my orders to the letter,

you shall die, or wish you had.”

The smiles fade. To Charmion: “They may go.”

Kleopatra looked out the window at the scene that had greeted her all the mornings of her days before her flight into exile.

There was little in the Royal Harbor to suggest Julius Caesar’s occupation of Alexandria. The pleasure vessels of Egypt’s

Royal Family rocked lazily at the dock. The morning fog had lifted, revealing a sky already white with heat above vivid blue

waters, and she was grateful that she was no longer breathing the deadening summer air of the Sinai.

Could it have been just yesterday that she was in the middle of that great blue sea, stowing away on a pirate’s vessel to

sneak back into her own country? She had dressed herself as well as she could without her servants, knowing that the last

leg of her journey would be a rigorous one, and that she could not be recognized when she arrived in the harbor of Alexandria.

She had let Dorinda, the wife of Apollodorus the pirate, help with her toilette, fixing and bejeweling the locks that had

been neglected while she was in exile. She would have done it herself, but her hands shook with anxiety; she had fought with

her advisers, rejecting their claims that it was too dangerous to reenter Egypt, and now she was faced with the task of using

stealth to slip past both her brother’s army and the Roman army to meet with Caesar.

Dorinda produced a silken scarf of spectacular colors and tied it about the queen’s waist, making an impressive show of her

young

strong figure. Kleopatra looked in the mirror and wondered if, in the woman’s hands, she looked like a queen or a prostitute

in training. But that was a look that men liked as well as the royal demeanor. Perhaps Apollodorus might try to pass her off

as a prostitute being taken to the mighty Caesar. Whatever got her into his quarters and whatever kept her there under his

goodwill would do.

The queen allowed the woman to kiss her hand, giving her a pair of heavy copper earrings and a bar of silver for her personal

purse before Apollodorus helped her lower herself to the small boat that awaited them just outside Egyptian waters. Dorinda

put on the earrings and shook them wildly, jiggling her extravagant body as she waved good-bye.

Now it was just Kleopatra and Apollodorus in the small vessel. She wondered what might happen if they faced adverse winds.

Would she have to row like a slave to get them to shore? No matter. She would do whatever was necessary and dream that it

was an adventure, like when she and her girlhood companion Mohama fantasized their important participation in political efforts.

She did not know at the time that such dangerous intrigues would someday be the reality of her waking, adult life. How she

would love to have the company of that beautiful brown Amazon-like woman now. But Mohama, along with the rest of Kleopatra’s

childish fantasies, was dead, all victims of the political realities set in motion by Rome and its determination to dominate

the world.

Apollodorus completed his duties at the sail and settled down next to her.

“What do you suppose moves this man Caesar?” she asked. Apollodorus was a pirate, an outlaw, a thief, yet Kleopatra had come

to value him as a sharp interpreter of human nature. But the pirate allowed that he could not figure the man, so paradoxical

were the reports of his character. Talk of his cruelty and his clemency were mixed. In the war against the Roman senators,

Caesar had spared almost everyone. He had captured Pompey’s officers in Gaul and let them go. Some he had seized as many as

four times during the war, and each time freed them again, telling them to say to Pompey that he wanted peace.

“If you submit to Caesar, he spares you. If you defy Caesar, he kills you,” said the pirate. “Perhaps that is the lesson Your

Majesty should take into the meeting. The towns in Greece that opened their gates to him have been rewarded. But the poor

inhabitants of Avaricum-they

are with the gods now-were turned over to his men for a drunken massacre. Merciful, cruel, I cannot judge. A complex man,

but I am sure, a great man.”

Suddenly it was dusk, and the pirate drew her attention to the harbor. In the fading sunlight, she saw the familiar Pharos

Lighthouse, the landmark of her youth, and one of the great hallmarks of her family’s reign over Egypt. The tower was bathed

in diffuse red light that lingered as the sun sank behind her into the depths of the Mediterranean. The eternal flame in its

top floor burned vigilantly. The imposing structure that had served as a marker of safe harbor for three centuries was the

genius of her ancestor, Ptolemy Philadelphus, and his sister-wife Arsinoe II, and now it welcomed her home. This was not the

first time she had approached her country from the vantage point of exile. But it was the first time she had returned to find

a flotilla of warships in a V formation pointing dangerously toward her city.

“These are not Egyptian vessels,” she said, noting their flags. “Some are Rhodian, some from Syria, some from Cilicia.”

“All territories from which Caesar might have called for reinforcements,” said Apollodorus.

“Warships in the harbor? What can this mean? That Alexandria is already at full-scale war with Caesar?” asked Kleopatra.

“So it appears. And now we must get you through Caesar’s navy and the army of your brother’s general, Achillas, before you

can have a conference with Caesar. I do not know if my contacts at the docks can help us in these circumstances. As Your Majesty

is well aware, in wartime, all policies change to meet the dire times. I’m afraid that our simple scheme of disguising you

as my wife may not serve us in these hazardous conditions.”

“I agree,” she said. Her heart began the now-familiar hammering in her chest, its punch taking over her body and consuming

her mental strength, pounding away at her brain. No, this cannot happen, she said to herself. I cannot submit to fear.

Only I and the gods may dictate my Fate. Not a heart, not an organ. I control my heart, my heart does not control me, she repeated over and over until the thud in

her ears gave way to the benevolent slurp of the placid waters, calming her nerves as they slapped haphazardly against the

boat. She put her head down and prayed.

Lady Isis, the Lady of Compassion, the Lady to whom I owe my fortune and my Fate. Protect me, sustain me, guide me as I make

this daring move so that I may continue to honor you and continue to serve the country of my mothers and fathers.

When she looked up from her prayer, she saw that they had drifted closer to the shore. Trapped now between the Rhodian and the Syrian flotillas, she realized

that she must take some kind of cover. How could she have so foolishly thought that she could just slip into the city where

she was known above all women? She must do something quickly to get herself out of sight.

She shared these thoughts with Apollodorus.

“It is not too late to turn around, Your Majesty-” he offered.

“No!” she interrupted him. “This is my country. My brother sits in the palace as if he were the sole ruler of Egypt. Caesar,

no doubt, is in receipt of my letter, and he awaits my arrival. I will not be shut out by these maritime monsters.” She raised

her hands as if to encompass all the vessels in the sea. “The gods will not have it, and I will not have it.”

Apollodorus said nothing. Kleopatra made another silent plea to the goddess. She stared into her lap waiting for inspiration

to descend upon her. She was for a moment lost in the intricate pattern of the Persian carpet that the men had thrown aboard

the boat at the last minute for the queen to sit on. An anonymous artisan had spent years of his life stitching the rows and

rows of symmetrical crosses into the silk. Suddenly, she pulled her head up straight and focused on the rug, mentally measuring

its dimensions. Its fine silk threads would not irritate the downy skin of a young woman, should she choose to lie upon it.

Or to roll herself inside of it.

The sun cast its final offering of light. Her companion’s square rock of a body sat helplessly waiting for the decision of

the queen as his boat drifted precariously close to the shore.

“Help me,” she said as she threw the rug on the floor of the boat and positioned herself at one end.

Apollodorus stood up and stared down at the queen, who lay with her hands over her chest like a mummy.

“But Your Majesty will suffocate,” he protested, stretching his palms out to her as if he hoped they would exercise upon her

a modicum of reason. “We must leave this place.”

The sun had set, and the boxlike form that hovered above her was only a silhouette against a darkening sky.

“Help me quickly, and do not waste our time with questions,” she said. “Julius Caesar is waiting.”

When the squatty Sicilian entered Caesar’s chamber to announce that he had a gift from the rightful queen of Egypt to lay

at Great Caesar’s feet, the dictator’s soldiers drew swords. But Caesar simply laughed and said he was anxious to see what

the exiled girl might smuggle through her brother’s guards.

“This is a mistake, sir,” said the captain of his guard. “These people are ready to take advantage of your good nature.”

“Then they, too, shall learn, shan’t they?” he replied.

The pirate lay the carpet before Caesar, using his own knife to clip the ties that bound it. As he slowly and carefully unrolled

it, Caesar could see that it was a fine example of the craftsmanship that was only to be found in the eastern countries, the

kind he had so envied when he was last at Pompey’s house in Rome. Suddenly, as if she were part of the geometrical pattern

itself, a girl rolled out from its folds, sat up cross-legged, and looked at him. Her small face was overly painted, with

too much jewelry in her thick brown hair, and a meretricious scarf tied about her tiny waist, showing off her comely body.

The young queen must be a woman of great humor to have sent Caesar a pirate’s little wench. She was not precisely lovely,

he thought, but handsome. She had full lips, or so he assumed under the paint. Her eyes were green and slanted upward, and

they challenged him now to speak to her, as if it was Caesar who should have to introduce himself to this little tart. But

it was the pirate who spoke first.

“Hail Queen Kleopatra, daughter of Isis, Lady of the Two Lands of Egypt.”

Caesar stood-a habit, though he remained unconvinced that the girl was not a decoy. She stood, too, but quickly motioned for

him to sit. Surely only a queen would have the guts to do that. He took his chair again, and she addressed him in Latin, not

giving him the opportunity to interrogate her, but telling him the story of how her brother and his

courtiers had placed her under house arrest and forced her to flee Alexandria and go into exile; how her brother’s regents

were representative of the anti-Roman faction in Egypt; how she had always carried out her late father’s policy of friendship

with Rome; and how, most importantly, once restored, she intended to repay the large loan that her father had taken from the

Roman moneylender, Rabirius, which she must have guessed was the real reason that Caesar had followed Pompey to Alexandria.

Before Caesar might reply to her speech, the queen said, “Shall we converse in Greek, General? It is a more precise language

for negotiation, don’t you agree?”

“As you wish,” Caesar replied. From there, the conversation was held in her native tongue and not his-not that it mattered.

He spoke Greek as if he had been born in Athens. He admired her ploy of simultaneously demonstrating her command of his native

tongue while diminishing it in comparison to the more sophisticated Greek language. There was no pride like that of the Greeks,

and this girl was obviously no exception.

But she had great charm and intelligence, so Caesar pledged her restoration, in accordance with her father’s will and the

nation’s tradition. He would have done so anyway, but now he could do it with pleasure. Not only would it please the young

queen, it would also irritate Pothinus, the dreadful eunuch whom Caesar despised. For Kleopatra’s part, she pledged a great

portion of her treasury that he might take with him back to Rome to satisfy Rabirius. A relief, he assured her, to have that

clacking old duck paid and off his back. Kleopatra laughed, remembering the sight of Rabirius’s great waddling ass as he was

chased out of Alexandria.

“I do hope you are enjoying our city,” Kleopatra said. “Are we occupying you as satisfactorily as you occupy us?”

Caesar felt he had no choice but to laugh. He told the girl about a lecture he had recently attended at the Mouseion, the

center for scholarly learning that he’d heard about all his years. She had studied there herself, she said, and in her exile

what she most had longed for was not her feathery bed nor the kitchen staff of one hundred who prepared for her the finest

meals on earth, but the books at the Great Library, and the visits of scholars, poets, and scientists who engaged her mind.

Now secure that she was once again at home and in charge, she relaxed in her seat and called for wine, stretching her thin,

shapely arm over the back of the couch and stretching her small sandaled feet in his direction. Caesar was startled at the

way she so easily issued commands in his presence, but it was her palace, after all. Before he knew it, however, they were

discussing the philosophy of domination, and he was drunk and praising Posidonius while she disputed every point.

“Posidonius has demonstrated that Rome, by embracing all the peoples of the world, secures all humanity into a commonwealth

under the gods,” Caesar explained. “Through submission, harmony is realized.”

A tiny laugh, almost a giggle, escaped Kleopatra’s lips despite herself. “Does Rome embrace, General? Is ’suffocation not a more appropriate word?” she asked, her eyes wide and twinkling. He did not know if she was

agitating him for the purpose of argument or to arouse him sexually. But with her enchanting voice that sounded almost like

a musical instrument, and the way she moved her body with sensuous fluidity, she was succeeding more at the latter.

“Suffocation, perhaps, but only in the service of the common good.”

“Whose good?”

“In Gaul, where I spent many years, tribes of men of the same bloodlines who speak the same language, who share common heritage,

have fought to destroy one another since time out of mind. I soon realized that while my army was at war with the tribes,

there was all the while a secret war in progress, one in which the tribes fought incessantly against one another. The same

is true in Illyricum and in Dacia. What you might perceive as an effort at domination is really a means to force peace. Only

by thralldom have they bought freedom from the tyranny of eternal tribal factions. But the first step is always the submission

of the collective will to a man of resolute vision. Do you take my meaning?”

“I see,” she said agreeably, and he wondered if she was storing up her thoughts to deliver an unexpected blow. “You do not

aim to suffocate, but rather to unite.”

“You are too young to have known Posidonius, my dear, but you would certainly have benefited by his acquaintance. He was most

well-traveled, having studied the arts and sciences over most of the known world.”

“Odd, we did not see him here, where the greatest philosophers in the world are known to gather,” she answered, much to Caesar’s annoyance. “And in any

event, this unity of peoples you describe, General, is only pertinent to those whom you believe you must improve. How might

it apply to we civilized Greeks, who require no improvement? How is it that we thrive under domination from a culture whose

arts and philosophies are so thoroughly derived from our own?”

It was too much, really, but she said it so charmingly, knowing as surely she must that she held no real power over him. He

could afford to be generous. She was so young, one and twenty, she had said, younger than his Julia would have been had she

lived. “Surely the gods were drunk on the day they made an imperious Greek girl the queen of a filthy-rich nation. Surely

I must be intoxicated to ensure the power of such a girl.”

“The Crown thanks you.”

“As you know, my child, as we have witnessed here in your own land, there must be a master. It’s as simple as that. In accordance

with the laws of the gods and the laws of nature. Otherwise, it’s a muddle. ’The strong do as they will while the weak suffer

what they must.’ If I may quote a Greek to a Greek.”

By this time, they were entirely alone. She had long ago dismissed the pirate, and Caesar his men. They sat facing each other

on two white linen couches with a table of refreshments between them. The queen regarded Caesar for some time, and he allowed

it, enjoying the flush of color across her high cheekbones and the way flashes of inspiration seemed to leap from her eyes.

“Is it not possible for the two civilized peoples, Greek and Roman, to rule side by side; one race of men of military might

in cooperation with another whose strength lies in the world of the intellect, the world of Art, Knowledge, and Beauty?”

“Possible, but not probable. If given the opportunity, men of means will always seek power and fortune.”

“And women of means as well,” she said.

“Yes, I have not seen that women lack ambition,” he replied. “And if a woman has sufficient means, then perhaps many things

are possible.”

“I’m relieved you think so.” She sat back, satisfied, her small hands folded in her lap, a quiet smile on her face as if she

shared some lovely humor with herself alone. Caesar was sure that they had not finished

with this line of discussion. But he wanted, at that moment, to seize her mind in his hands as if she were another territory

to be conquered in the name of Rome and of unity. Yet she was not a woman to be merely taken. Here was a woman, he thought,

who if giving herself of her own volition, would give the world.

“But we have parried enough, Your Majesty,” Caesar said, rising. “You’ve vexed an old man quite enough for one day. Now come

to bed. You are under my protection.”

But she did not rise with him. “General, just when I thought your command of Greek was beyond reproach, I find that you make

a linguistic mistake.”

“Caesar does not make linguistic mistakes,” he replied. What now? More argument with this fetching creature? Was she determined

to try his patience?

“You said, come to bed, when surely you meant go to bed.” Again, she looked at him as if she was either laughing at h

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...