- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

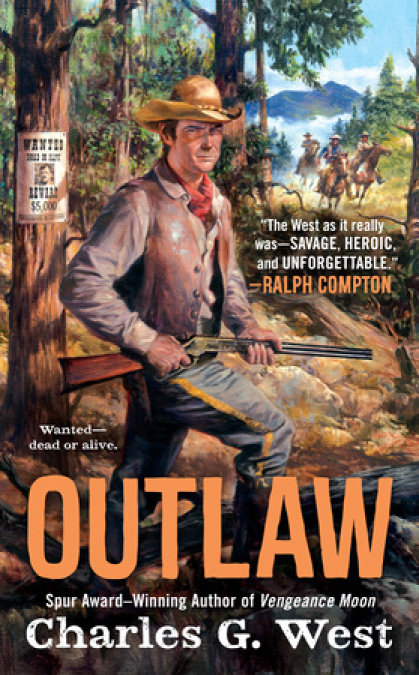

Action-packed western adventure from the author of Crow Creek Crossing.

AN OUTLAW IS BORN

When war came to the Shenandoah Valley, Matt Slaughter and his older brother joined the Confederate army. But three years defending his homeland as a sniper has weighed heavily on Matt’s conscience. With the cause lost, the brothers desert—only to find upon their arrival home that Owen’s farm has fallen into the hands of swindlers…

Then, after his brother accidentally kills a Union officer, Matt takes the blame. But now—facing a sham trial and a noose—he escapes to the west, where he saves the life of another fugitive down-and-outer. Both men are a breed apart from other outlaws. Neither kills for pleasure or steals for profit. But that doesn’t matter to the cold-blooded men who are going to give them hell to pay—and get the same in return…

Release date: May 2, 2006

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 288

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Outlaw

Charles G. West

YANKEE JUSTICE

Captain Belton turned his attention to the prisoner. He studied the young man intently. “Another belligerent Rebel who doesn’t know he’s been whipped,” he remarked. “What unit did you serve with, Reb?”

Matt, who had been studying the captain just as closely, hesitated a moment before replying, “Twenty-second Virginia Cavalry.”

“Twenty-second, eh? I guess they didn’t teach you to stand up in the presence of an officer.”

“Not a Yankee officer, I reckon they didn’t,” Matt replied.

A wry smile creased the captain’s face. “Still got a few burrs, ain’t you? Well, let me tell you what happens to smart young men like yourself who murder an officer of the U.S. Army. We’re gonna take you back to Lexington in chains, so all the other Rebs can see you. Then we’re gonna hold a trial, so that everybody knows we stand for justice. Then we’re gonna hang you in the square to teach the rest of your kind a lesson.”

There was no doubt in Matt’s mind that a trial would be no more than a formality and the prelude to a hanging. The question before him was when to escape, for he knew he would rather a bullet in the back than a rope around the neck.

OUTLAW

Charles G. West

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Making his way silently up through the dark forest that covered the east slope of the ridge, a Confederate sniper stopped and dropped to one knee to listen to the sounds of the night. Above him a Union picket passed in the darkness, following the narrow path that circled the crest of the hill. He had spotted the Union soldier when still some twenty yards away from where he presently knelt, and now he paused to allow time for the unsuspecting sentry to reverse his post. On the neighboring ridge, an owl hooted softly in the darkness. Several yards to his right there was a gentle rustle of leaves as a rodent scurried to seek a hiding place, aware that he might be prominent on the owl’s menu. Matt paid the rodent no attention. He was accustomed to the night sounds of the forest, and he had his own neck to worry about.

Come on, dammit, I ain’t got all night, he silently urged the sentry, impatient to make his way across the ridge. Unaware of the Confederate marksman less than a few yards directly below him, the Union soldier paused to light his pipe. A dense cloud of tobacco smoke spiraled around the man’s head as he pulled vigorously on his pipe, tamped the load down, and relit it. Satisfied that it was lit to stay, he began his tour again, completely unaware of the inviting mark he presented. It was this Yankee’s good fortune that he was not this night’s primary target. Matt had been sent to seek a more specific target. He had been told only that part of Sheridan’s troops, under General George Crook, were encamped along the bluffs overlooking Cedar Creek. His orders were to infiltrate the Union picket lines, and if possible, to take out any officers he could get in his sights. It would be unlikely that he would be able to get close enough for a shot at Crook himself, but the higher the rank, the more demoralizing it would be for the Union soldiers.

While he waited for the picket to move on, Matt glanced around him in the darkness to make sure he was still undiscovered. He unconsciously reached up to stroke a small St. Christopher’s medal that hung on a silver chain around his neck, a gift from his mother. His brother wore one just like it. Not really sure who St. Christopher was, both boys considered the medals to be good luck charms.

Matt Slaughter had spent a good portion of his young life in the hills and forests of the Shenandoah Valley, hunting every wild critter that dwelt there. He felt at home in the forest, alone, away from the confusion of his cavalry unit. His commanding officer, Captain Miles Francis, had recognized the wildness in the young volunteer from the central valley and was not at all surprised that the quiet young man proved to be the best marksman in Company K. Consequently, Francis was quick to use Matt’s woodland skills to the regiment’s advantage.

Thoughts of his service since joining the 22nd Virginia Cavalry flashed through Matt’s mind as he readied himself to continue his climb up the slope. It had seemed a long time since the summer of 1863 and the formation of the 22nd. He had participated in most of the fighting in the Shenandoah Valley from the time his unit was thrown into the Third Battle of Winchester a little over a year before. It was a glorious effort, and a decisive victory for the South. But things had not gone well for the Confederate Army in the Shenandoah Valley since, for the Union troops had regrouped and come back with a vengeance. Now his regiment was engaged in little more than harassing attacks against an overpowering Union force—fighting and retreating—with the sickening knowledge that the valley was no longer theirs.

Slowly rising to his feet again, Matt paused to look around once more, the careful precaution of a man who had no one to rely on but himself. It was late October. The leaves were already changing color on the hardwoods, but in the gray predawn light, they appeared cold and lifeless. He thought of his role in this fight: marksman, sharpshooter, sniper. By any name, the term that lodged in his mind was assassin. At first, he looked upon his assignments as no more than soldiering. Like any other soldier in the line, he was doing his duty as ordered. But after a while, it soured on him. In an infantry or cavalry charge, an individual was simply part of one army against another army. But when he killed, it was a personal thing, and the thought was beginning to weigh heavily on his conscience. In his mind, there was nothing heroic about slipping silently through the forest to wait in ambush, to kill, and then to slip away again. He no longer took pride in being the best shot in the regiment. In fact, many times he felt no better than a low-down bushwhacker. Best get my mind back on my business, he reprimanded himself, before I get a Yankee miniball in my behind.

He paused only briefly to glance in both directions when he crossed over the path the picket paced. Then he disappeared into the trees that covered the crown of the hill. Making his way down the other side, he continued until the fires of the Union camp were in sight on the bluffs above the creek. Slinging his rifle so he could free both hands to help scale the steep bluffs, he climbed up to a point high enough to be able to see into the camp. Edging a little closer, he positioned himself to look over the encampment, making note of the sentries posted about the perimeter. Satisfied that he had a clear view of the officers’ tents, he next determined his route of escape, for he would not be able to retreat the way he had come. His primary means of escape, his horse, was tied to a gum tree a quarter of a mile beyond the other side of the ridge he had just crossed. After giving it a couple minutes’ thought, he decided his best route would be to follow the creek to a point where the bluffs were steepest. From there, he could scramble down and cross over. Carrying nothing more than his rifle and ammunition, he was confident that he could outrun anyone giving chase. With that decision made, he settled himself in a thicket to wait for a target.

In no particular hurry now—for it would be at least an hour before daylight—he readied his weapon. One of only two issued to his company, the long, British-made Whitworth was especially suited for his purpose. With its tubular telescopic sight mounted on a hexagonal barrel, he could hit a target up to eighteen hundred yards away. And that was six or seven hundred yards more range than the Enfields carried by most of the infantry companies attached to the regiment. The Whitworth had to be loaded down the muzzle, which was not ideal in a skirmish. But for accuracy, there was no better weapon.

Now came the part he hated—waiting—for there was too much time to think over what he was about to do. If the opportunity presented itself, and it usually did, somebody’s wife was about to become a widow. What seemed unfair about it was the simple fact that his victim would not be prepared to die. There would be no battle raging, no suicidal charge upon an enemy position, no anticipation of the possibility of the fatal shot. Assassin. The word kept coming back to haunt him. He hated it. It was a word without honor.

The only person with whom he had discussed the issue was Lieutenant Gunter. Gunter was a favorite among the men of K Company. A giant of a man, the jovial second lieutenant always seemed to have a word of encouragement for everyone. He had sensed the basic decency in the young soldier from Rockbridge County, and often took time to talk with Matt about his job. It was Gunter who advised Matt to think not of his targets as individuals, but to picture them only as faceless bluecoats. If further encouragement was needed, the lieutenant suggested thinking of the beautiful Shenandoah Valley, now laid waste by Sheridan’s invading troops. Matt had tried to think of these things, but the word that lingered most in his mind was assassin.

First light finally began its gentle intrusion upon the darkened forest, creeping almost imperceptibly until the individual trees began to take shape in the morning mist. A light fog lay across the creek bottom, but was not dense enough to obscure the tents above the creek. Captain Francis had ordered him to hold his fire until first light, which should be around five o’clock. The captain would not elaborate, but Matt figured that the company was to be involved in an early morning assault upon General Crook’s division. It shouldn’t be long now. A thought of his brother, Owen, flashed through his mind then.

About twelve miles back down the Valley Pike, his brother was most likely stirring from his blanket. Owen always woke before first light, a habit ingrained from long years working a farm. Unlike Matt, Owen was a family man. Older by two years, he had volunteered to fight for the sole reason that the valley was his home, and he felt a strong sense of duty to defend it and his family from the Union invaders. Poor Owen, Matt thought, he’s got no business in this fight. He should be home with Abby and his two sons. Both brothers thought the war would never come to the Shenandoah, but come it had, like a deadly plague of locusts, leaving the very ground gutted in its wake. Only ten days before, at Tom’s Brook, Matt’s unit had fought over ground less than thirty miles from his little parcel of land near the river before being forced to retreat back to Woodstock. They had been whipped badly on that day. The memory of it still smarted. The Yankees chased them twenty miles up the Valley Pike and then eight miles up the Back Road. The inglorious retreat came to be known as the Woodstock Races. He wondered now if his cabin and Owen’s house had been spared when the Union troops swept through. There had been no opportunity to find out.

Suddenly his senses were brought back to the present, for the Union camp came to life as soldiers crawled out of tents and blankets. Soon fires were reborn all along the bluffs, and the sounds of a waking army filtered through the hardwoods. Matt sat motionless as a Union sergeant walked out among the trees, approaching to within ten yards of him before stopping to empty his bladder. With no thought of panic, Matt watched until the soldier finished and returned to the camp. Then he turned his attention back to concentrate on the officers’ tents. In a few minutes time, a soldier appeared at the flap of the closest tent carrying a cup of coffee. Time to go to work, Matt told himself, forcing himself to ignore the feeling of reluctance that always came. Rising to one knee he brought his rifle up and rested the barrel in the fork of a young dogwood. Sighting through the long telescopic sight, he trained the weapon on the tent flap. Moments passed. Then a gray-whiskered face appeared and stepped outside to accept the coffee. He wore no tunic, so his rank could not be determined. But since he was the one who was served coffee, Matt guessed that he was in command.

Matt took careful aim. His intent was always to make the shot count, to kill his target as quickly as possible with minimal suffering. At a range of one hundred yards, he was confident enough to take a head shot, so he trained his sights slightly above the gray whiskers. He waited a few moments to allow his victim a sip or two of hot coffee before squeezing the trigger. The face in the telescopic sight disappeared with the sharp report of the Whitworth rifle. With no hesitation, but without unnecessary haste, Matt reloaded his weapon, ramming home another bolt, as the odd-shaped bullets were called. Although the sudden shot had caused pandemonium in the Union camp, with soldiers running for cover, Matt was not yet concerned with escape. He felt reasonably sure that his muzzle blast had not been seen, especially with the fog rising from the creek. His rifle loaded, he turned to sight on the second tent. As he expected, an officer emerged from the tent, a pistol in his hand. He took one step toward his fallen commander before collapsing on the ground, shot through the heart.

There it was, that little sick feeling Matt always experienced when he assassinated an unsuspecting victim. It made no difference that the two officers were the enemy, and would send troops forward to kill him and his comrades. In his mind, it was outright murder. As Lieutenant Gunter advised, he tried to think of the officers as barbarians, laying waste to the Shenandoah.

His job done, Matt wasted little time withdrawing from the thicket that had shielded him. There were probably two or three more officers in the camp, but he wasn’t willing to risk another shot. His assignment had been to demoralize the enemy by killing the commanding officers. At this point in the war, it seemed a pointless task, but he had done it one more time, and had accepted it as his duty.

Making his way along the creek at a steady trot, he listened to the excited sounds behind him, alert to any that might indicate pursuit. He knew from experience that at first the soldiers would be seeking cover in anticipation of an attack upon their position. Not until they realized that there was no Confederate force about to descend upon them would they mount a hunting party to go after the sniper. By that time, he planned to be long gone.

He had barely crossed over to the other side of the creek when he heard the opening barrage of the battle behind him. Confused, he immediately turned and worked his way back along the bank to see for himself. “Damn!” he uttered as he spotted a wave of Confederate infantry sweeping along the bluffs, flanking the Union position. They must have marched all night to get here, he thought. This was what Captain Francis had hinted at the day before. From his vantage point on the creek bank, Matt could see that the Confederate attack was successful, for Crook’s soldiers were already falling back in retreat. God, he thought, we damn sure need a victory after Tom’s Brook.

Giving no thought toward joining in the Rebel assault, he continued to watch until the Confederate infantry succeeded in driving the Union soldiers back toward Middletown. His reasoning was simple: he was apt to get shot by one of his own comrades if he came running out of the woods to join them. He elected to withdraw and go back to retrieve his horse. He had done enough killing for one day.

* * *

When he found his company later in the morning, he was greeted by several of his friends. Still basking in the heady wine of victory, they offered good-natured derision. “Well, lookee who decided to show up,” a lanky farm boy from Lexington called out.

“Damn, Slaughter,” another asked, “where the hell were you? You missed a helluva party.”

Matt just smiled in reply. He looked around him at the soldiers taking their leisure. “Anybody seen my brother?”

“I saw him earlier this morning,” the lanky farm boy replied. “He was with Lieutenant Lowder when we charged up the bluffs. I expect he’s down the line a piece.” He pointed toward the lower end of the camp. Matt nodded and took his leave.

He found Owen perched on a log, drinking a cup of coffee. His brother’s eyes brightened when he spotted Matt striding toward him. When Matt approached, Owen got up to greet him, extending his coffee cup. “This is the last of the coffee beans,” he said.

Matt accepted the cup and took a quick swallow of the fiery-hot liquid, then handed it back. “Thanks. I didn’t expect to see you today.”

“We didn’t expect to be here,” Owen replied. “General Gordon ordered everybody out for a night march. We got here at about four o’clock this morning and waited around for about an hour before the attack.”

Matt smiled, grateful that his brother had survived another skirmish. Although Owen was the elder, Matt felt a sense of responsibility to make sure his brother returned home safely to Abby and the boys. He had always felt responsible for Owen, ever since their parents had perished in a cabin fire. He sat down on the log. “Yeah, if I’d have lingered a few minutes longer this mornin’, one of you boys mighta shot me. I’d just left that creek bank when I heard all hell break loose behind me.”

“We heard two rifle shots not more than ten or fifteen minutes before we got the signal to advance,” Owen said, nodding his head as he recalled. “Was that you? It sounded like that Whitworth, come to think of it.”

“I was wishin’ I had my carbine with me when I heard all the shootin’. I thought it was the Union Army coming down on me.” He gave Owen a wide grin, happy with the knowledge that both he and his brother had survived yet another battle.

* * *

The men of General Early’s Confederate forces were not to celebrate their victory long, for General Sheridan returned to take command of his demoralized Union troops. He mounted a counterattack at around three o’clock that afternoon, driving the men in gray back up the valley in an all-out retreat. There were several more battles fought in November, but the Confederate forces were so badly outmatched that the Shenandoah Valley was virtually lost before spring of 1865. Through it all, Matt and Owen Slaughter managed to stay alive. In a final crushing blow by Union forces near Waynesboro, backed up to the South River, their company put up a fight for as long as they had ammunition. Finally, it was every man for himself as General Early fled along with some of his aides, leaving the valley in the hands of the Union Army. Seeing what was developing, Matt grabbed Owen by the arm. “The officers have cut and run,” he exclaimed. “Come on, we ain’t stayin’ here to get captured!” Along with droves of others, the two brothers escaped up the mountainside. The war was over for the Slaughter boys.

Chapter 2

It took four days of hard riding along mountain trails and back roads before they reached the last low ridge between them and Owen’s farm. During that time, they sighted only occasional Union patrols along the main road. Still, they thought it best to avoid the Valley Pike. With no ammunition to spend, the two were unable to take advantage of any game they happened upon except an occasional squirrel or rabbit curious enough to get caught in a snare.

When at last they reached the ridge that protected his farm on the eastern side of the little valley, Owen galloped ahead to the crest, unable to contain his excitement. When Matt joined his brother at the top of the ridge, he found Owen sitting silent and disconsolate. Below them, the fields were black and scorched. The house was a pile of charred timbers around the stone fireplace, its chimney standing like a solitary grave marker. The two brothers stared dejectedly at the remains of the second Slaughter homestead burned to the ground, the first having been the cabin that had claimed the lives of their parents.

With thoughts of his parents’ fate with the burning of the original cabin, it was all Owen could do to keep from choking on a sob. He looked fearfully at his brother and gasped, “Abby.” Then he kicked his horse hard with his heels and drove recklessly down the slope. Matt followed, instinctively scanning the valley back and forth with his eyes, cautious in case there were Union soldiers about.

Owen was out of the saddle before his horse came fully to a halt, frantically pulling burnt timbers this way and that, searching for what he hoped he would not find. He picked up broken pieces of dishes and scraps of singed cloth, remnants of his life, now destroyed. Finding nothing whole, he finally sank to his knees defeated, tears streaming down his face.

Matt watched his brother’s sorrowful return to his home, in silence to that point. Then he sought to comfort him. “We’ll find Abby and the boys,” he said. “We’ll rebuild the house. The Yankees burned the crops, but they couldn’t hurt the ground. We’ve still got time to plant this spring.” He paused to judge if his words were enough to rally his brother. “You know, Abby most likely took the boys to my cabin. Maybe the Yankees didn’t find my place.”

Owen looked up hopefully. “Sure, that’s probably where they are. Come on!” In the saddle again, they loped off along the river, following a narrow trail that led through a wooded gulch to a small meadow beyond. There, at the far end of the meadow, the simple log cabin remained, apparently unmolested by Union troops. The brothers galloped across the open expanse of grass.

“Ma!” Jeremy exclaimed, “Somebody’s comin’.” The nine-year-old ran to fetch his mother. Abby Slaughter moved to the window. Six-year-old David clung to his mother’s skirt as she peered out to see who it might be. Not certain if her eyes were deceiving her, she continued to stare at the two riders driving hard toward the cabin. In the next instant she was sure. It was Owen and Matt. Suddenly she felt as if her strength had deserted her and she almost collapsed, forcing her to hold on to the windowsill for support. There had been no news after the fighting at Cedar Creek and the Confederate retreat. The only word that had reached the tiny valley was that hundreds of men on both sides had been killed. Abby had tried to steel herself to the possibility that Owen would not be coming back. But in her heart she feared she could not survive if he had perished.

She wiped the tears from her eyes, her fearful expression replaced by one of joy as the riders approached. She ran to the door, almost knocking David to the floor in the process, hurrying to greet her husband. Owen leaped from the saddle to meet her. Matt, grinning with pleasure, dismounted and watched the joyful reunion. Abby released Owen long enough to give Matt a hug, then flew into her husband’s arms again, her sons clinging to their father’s legs.

“We saw the house,” Owen said, “at least where the house once stood.” He looked at his wife, reassuring her. “Don’t you fret, honey, me and Matt’ll build us a better one.” Matt nodded in agreement. Owen continued. “It’ll soon be time for spring plowin’. We’ll have us a garden goin’ in no time, and we can stay here till Matt and I can build the house back.” He turned to his brother. “If that’s all right with you, Matt.”

Matt grinned, surprised that Owen would even bother to ask. “Of course it’s all right,” he said. “I’m just sorry it’s so small.”

Abby placed a hand on her brother-in-law’s arm. “I don’t know what we would have done if the Yankees had burned this cabin down. I don’t know where the children and I would have gone.”

He patted her hand gently. “Well, you know you’re welcome to the cabin as long as you need it.” He smiled at Owen. “Matter of fact, I think I’ll sleep in the barn. I’ve spent so many nights sleepin’ with my horse till I’m not sure I can stand being shut up in a cabin.”

“Bless you, Matt,” Abby whispered. Then realizing that the two men were probably hungry, she said, “Come on inside, and I’ll fix something to eat. I’ve got some corn left, and a little piece of side meat. There may be enough flour to make a little gravy.”

Matt and Owen exchanged glances. Then Owen spoke. “Is that all the food you’ve got?” When she nodded silently, he asked, “What happened to the money I buried under the comer of the corn crib?”

“Owen,” she exclaimed in despair. “It’s all gone—long ago.” When she saw his look of disbelief, she insisted, “You’ve been gone for over a year. All we’ve had to eat for the last six months is some corn and some side meat from time to time from Reverend Parker and his wife. The only way I could get food for the children was to borrow money from Zachary Boston.” She read his eyes and pleaded her case. “I had no choice. My babies were hungry. He said it was all right, and that you could just pay him back when you came home.”

Owen shook his head. Zachary Boston was about as unlikely a man to help a neighbor in need as anyone Owen could think of. I guess the war does peculiar things to people, he thought. Maybe it taught an ol’ skinflint like Zachary Boston to give a helping hand. “I’m real sorry, honey. I’m sorry it’s been so hard for you. But I’m home now. We’ll get that place up and runnin’ again.”

Abby pulled a chair back from the table and sat down, suddenly overcome with a feeling of exhaustion. She had not let herself dwell on the hardship of having spent so many long months of waiting, not knowing if her husband would return to her. It had been her endeavor to never look beyond the day that was presently before her, trusting in God to take care of things. It had not been easy when weeks would pass with no word of Owen’s unit, or even where the fighting was. But now she sank back against the chair, watching the two brothers eat the meager repast she had scraped together, and she knew that everything would be all right again. Owen was home.

She didn’t realize that she was smiling as she gazed at the two strapping young men. Though dirty and unshaven, they looked beautiful to her. Owen was the shorter by an inch, but heavier through the chest and darker of complexion. She turned her gaze toward her brother-in-law. Matt, the fairer of the two, had always put her in mind of a mountain lion, moving with a wild grace that seemed effortless. There was something different about him. He had grown a mustache. She smiled warmly at him when he glanced up to meet her gaze. Then she looked back at her husband. It was so good to have them back, both of them. The long, empty months were finally over.

* * *

The next month passed quickly, with the two brothers working every day to restore the house and prepare the scorched fields for planting. Seed was supplied by Reverend Parker, who insisted that Owen could repay him by coming to services every Sunday. Matt even attended one Sunday in order to personally thank Parker for his help.

Owen’s farm and Matt’s small strip of land by the river were not subject to much traffic from the world outside. It was almost May when word of Lee’s surrender reached the little hollow deep in the valley. The news was met with stoic regret from both Matt and Owen, but it came as no surprise. As far as they were concerned, the war had ended in March when they had retreated up that mountain along with their officers.

Some of the men at church had brought news that Union soldiers had been posted in Lexington, and the area was officially under martial law. The news was somewhat unsettling, but the brothers and their closest neighbors didn’t anticipate seeing any soldiers in their isolated part of the valley. There was no time to worry about who won, anyway. Now was the time to recover what had been lost in that unfortunate struggle between North and South. All that mattered was the land. There were no plantations in the Shenandoah Valley, no slaves to be freed. Every man they knew worked the land with his own back, and the two brothers set out to reclaim Owen’s farm with a determination that already showed dramatic results. By the first of June, crops were in the fields, and the house

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...