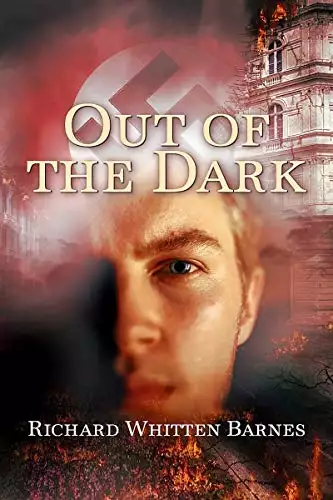

One

1933

First memories are hard to distinguish between what was truly experienced and events one has merely repeatedly heard about since those nascent years. But

since the time I was seven, I have a clear memory of the year 1933—probably due to two indelibly fixed images.

We had moved from Cologne to Berlin when the government took control of Luft Hanse AG where my father worked as a pilot. The company was being renamed Deutsche Lufthansa.

On that first day in the capital, we were taken on a short tour en route to our new apartment. I clearly recall being impressed with the ride down Unter den

Linden, the huge poster of the Führer, the Brandenburg Gate, and the destroyed building they told me had been the Reichstag.

I asked, “What happened, Papa?”

“A fire,” was his terse response

“I mean, how did it—”

“No one knows,” he said, seeming to wish the topic to end.

Our driver, who was in a uniform with a swastika armband opined, “They got the dirty Red, and he’ll hang!”

“One can’t be sure,” my father quietly said, and I saw my mother place a cautionary hand on his arm.

The driver looked up at his mirror. “It’s true! I heard Herr Göring say it!”

“Who is Herr Göring?” I wondered aloud.

“Quiet, Erich,” my father said.

The driver responded. “Oho! He’s the famous fighter pilot from the Great War, young man, and now in charge of the police called the Gestapo. He knows

everything, so be a good boy. You don’t want him after you!”

“My father is a pilot, too,” I began, but Pappas’s vise grip in my arm cut me off.

The driver only nodded and conversation ceased for the duration of the trip to our new home.

~ * ~

The new apartment was in the northern part of the city. It was large enough for my younger sister Käte and me to have separate rooms. Our building was on a

boulevard in a prosperous neighborhood where,opposite, fashionable shops lined the street. For a boy who had spent his entire life playingn open fields, my new environment was strange. Two

paces from the curb led to a heavy door that opened into a tiled vestibule. Rows of brass mailboxes lined one wall. Another door, accessed only with a key, led to carpeted stairs. The stairway smelled like the mothballs Mutti would use to store our winter things.

Our apartment was on the third of four floors. Where would I go to play?Out of the Dark Richard Whitten Barnes

I remember spending a lot of time that first year playing in my bedroom. It wasfrom my bedroom window that I had my first encounter with overt anti-Semitism. At that age, I had heard talk outside of my family about the Jews being, somehow, not to be trusted, but what I saw from my window was more

pronounced. Young men dressed in brown shirts and caps were painting shop windows with the word “Jude” and star symbols. Others were preventing entry

into the shops.

These men, to my mind, were people of authority. No one was stopping them. Perhaps what I had heard about the Jews was true. This was the adult world

sanctioning anti-Semitism and I had no reason to question it.

A week later, the same people and others in civilian clothes were throwing papers and books onto a large fire that had been built in the center of the boulevard. I saw a similar fire on the next block. When

I asked my parents about it, the subject was changed.

Undeterred, I found out later the books were about or written by Jews.

~ * ~

Käte was a year to the month younger than I. In Cologne, we had lived near the airfield, in a rural setting well away from the city. We were inseparable.

It was a paradise for us with a nearby pond fed by a brook and a copse of trees that was a forest to us. We, however, had few other children to play with and the

days were spent making up adventures.

She was like a twin brother, willing to climb trees and skip stones in the pond. That is not to say we were alike in other respects. Käte seemed to have a different, less obvious way of looking at things, analyzing possibilities, whereas I tended to jump to conclusions.

She would take chances, but only after thoughtful consideration of the outcome. In Berlin, we were assigned to separate schools, and while we still shared

confidences, our separate bedrooms muted the influence each of us had on the other.

My recollections of school in those first months in Berlin are also clear. Foremost in my memory is that of my new teacher, Herr Maurer. Until this time, I had had

only two teachers, both women, who maintained discipline while still allowing an easy dialogue with their young charges. Herr Maurer was a radical change for me.

He was not a tall person, rather plump, black hair slicked down on his scalp, round black-rimmed spectacles, and every day the same black-frocked coat

over suspenders and a not-so-white shirt. He had a deep, resonant voice that belied his mundane appearance. While less than imposing, he maintained

an atmosphere of respect approaching fear in this class of seven-year-olds. I accepted every word he uttered as gospel.

Maurer taught by rote. Rarely would he recognize a raised hand unless he had specifically addressed a student. We were lectured on arithmetic, geography,

and history—the latter being highly seasoned with the abuses Germany had suffered by the allied powers since the 1918 armistice and the promise of the New Reich.

It was in this class that I was introduced to the concept of the purity and superiority of the Aryan race.

My mop of blonde hair made me a favorite of Herr Maurer. It was easy for me to accept his ideas as truth. I was a good student and rarely bore the brunt of his inevitable scolding for a wrong answer.

Here is where I first noticed some of the older boys wearing the smart-looking uniforms of the Deutsches Jungvolk. The previous year in Cologne, such uniforms were unknown in our small suburban

school. I was impressed! I wanted one of those peaked military caps, the shiny belt buckle, neckerchief, and leather shoulder strap.

Surprisingly, my parents were not as enthusiastic as I. Other similar organizations had been recently banned by the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche

Arbitepartei (NSDAP, or Nazi) party, and they thought it unfair that I could not join the Boy Scouts as my father had. It turned out I wasn’t old enough in any

event. But it was September, and in four months I would reach the required age of eight. Herr Maurer was a zealous Nazi. Aphotograph of Herr Hitler—we had been instructed to begin referring to him only as “Führer”—was prominently displayed

over the blackboard behind his desk. Each morning we stood and with arms upraised in the Hitlergruß, we pledged our fealty to Adolf Hitler.

Maurer had a way of injecting National Socialist ideas into almost every subject. He politicized the learning of the new handwriting style, saying the old

script was a throwback to the days of the Weimar Republic and insisted we dispense with any of the old letterings in anything we wrote. He could be instructing us on something as sterile as arithmetic and have the session devolve into a rant on the current depression

and how the American Wall Street Jews caused it.

It was in this school that I became aware of the tendency of my peers to follow my lead. Perhaps the fact that I was tall for my age and smart in my schoolwork gave me a mien of leadership. Whatever

the reason, I accepted the role, one I never thought to relinquish.

At home, it was a completely different story. I have said that I revered my father; a hero in my young eyes. He, like the famous Göring, had been a Fliegertruppen fighter pilot in the war. He rarely talked about his experiences, but my mother would let me look at his Iron Crosses (Grades I and II) and his

Friedrich Order Star which she told me was for exceptional bravery.

Mutti had been an amateur athlete as a young woman growing up in Hannover where her future husband’s squadron, or Jagdstaffel, was disbanded in 1918. She was more demonstrative of her affection than

Papa, but also a no-nonsense disciplinarian. I never put anything past her.

Käte, while a half head shorter and smaller, was in no way my inferior at home or elsewhere. She knew me well and was quick to put straight whatever nonsense I might utter or do. I never resented that trait but admired and respected her opinion from my earliest memory.

Perhaps these three strong personalities I encountered at home influenced my own as well. This, plus the adjustment of moving from our bucolic life near Cologne to a Berlin apartment and a new school

resulted in 1933 being a pivotal year in forming who I would become in later life.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved