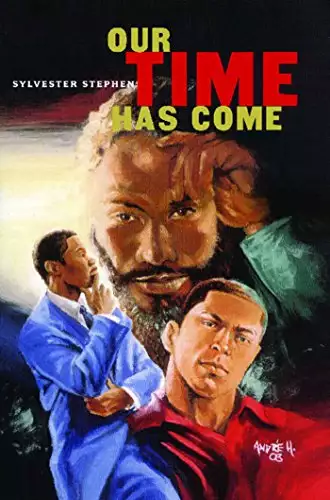

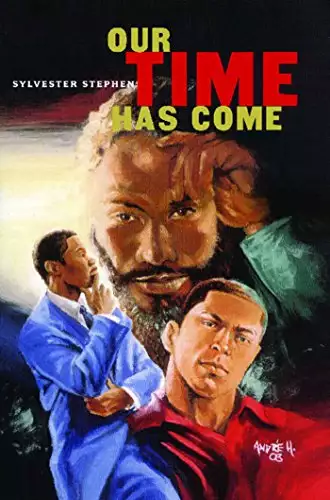

Our Time Has Come

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

An ENGAGING and PROVOCATIVE new novel that CHALLENGES all the political, social, and economic INADEQUACIES of the AMERICAN CIVIL RIGHTS System. In a dazzling display of political insight and masterful storytelling, Sylvester Stephens presents a new novel about what has been wrong throughout America's past -- and what can be made right in its future. Solomon Chambers is born in Saginaw, Michigan, in 1940. His parents and his uncle moved to Michigan from Mississippi years earlier, hoping to avoid the racism of their home state. Solomon eventually becomes a lawyer, and when his uncle is murdered in Mississippi he serves as a witness for the prosecution -- and has his first real brush with the reality of racism. Later, in the year 2007, Affirmative Action and the Voting Rights Acts are abolished. When African-Americans charge the United States government with violating their constitutional rights, Solomon is called to try the most significant case of his career, and one of the most important in history. Full of powerful political commentary and dramatic narrative, Our Time Has Come is the inspiring story of a man who must confront himself and his own history -- and fight for a just future that can heal the pains of a violent past.

Release date: October 4, 2011

Publisher: Strebor Books

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Our Time Has Come

Sylvester Stephens

SAGINAW, MICHIGAN, 2008

Every family has a story. A chronology of time, where names and people in the history of that family serve as a vessel from the past to the present. This is the story of my family. A story about the prophecy of a man named Alexander Chambers, told through the hearts and souls of his children. A story that tells of three generations to fulfill one prophecy. The first generation was given the prophecy, the second generation interpreted the prophecy, and the third generation fulfilled the prophecy. I am the fourth generation of the Chambers legacy, and though my father Solomon Chambers would fulfill the prophecy, I am blessed with revealing the prophecy to you.

My great-grandfather, Alexander Chambers, was born in a place called Derma County, Mississippi, in 1855. He was an only child, and a slave. He was college-educated, and not accepted very well by white people because of it. He met my great-grandmother Annie Mae while they were children growing up on the West Plantation in Derma County, Mississippi. After the Emancipation Proclamation, slavery was abolished, and Negro people were freed. However, my great-grandparents continued to work on the West Plantation. They eventually married and had one child, a son they would name Isaiah, my grandfather. He met and wedded my grandmother, Orabell, whom I loved with all of my heart. They, too, were blessed with only one child, Solomon, my father. We are generations of ones, for I, too, am an only child.

My great-grandfather Alexander decided his family would not be just another colored family satisfied with being free on paper, and not free in life. He wanted his family to be prideful, and understand that freedom is given to all men at birth. Great-grandfather Alexander believed that his son Isaiah had the hands of God upon him, and he was destined for greatness.

My great-grandfather created a book to chronicle our family's history. He said it would be our family Bible. He wrote the title of our family Bible: Our Time Has Come! Our Time Has Come originated from his inspiration that his family would one day overcome the manacles of slavery, and rise to the pinnacle of humanity. He started the Chambers Bible with the first verse. Each generation was to incorporate his, or her, new verse to pass on to the next generation to come. And these are the words of our family Bible:

"Our Time Has Come"

Alexander and Annie Mae Chambers -- 1902

The dawning of a new millennium, sing songs of freedom, Our Time Has

Come. Our God send signs it's time for unity, this is our destiny,

Our Time Has Come.

Isaiah and Orabell Chambers -- 1939

Today begins the day, thought never be, when we rise, in unity, One God,

One Love. Our voices be the sound of victory, when we, stand proud

and sing, Our Time Has Come!

Solomon and Sunshine Chambers -- ????

These are the inspirational words of my great-grandfather, and my grandfather. But here it is in the year of our Lord 2008, and my father has yet to add his generation's verse to the family's Bible. He is a sixty-eight-year-old man and his opportunity to pass the Bible to me with his verse inscribed, is rapidly decreasing.

My father does not believe in the prophecy as my grandfather, and great-grandfather. He believes in today, and making the most of it. He wants his legacy to be remembered for what he has done as a scholar and professional, and not as a martyr, or activist. He does not believe in the struggle for the advancement of Black people. He believes that every man should make his own way through the means of education; regardless of the circumstances. He believes that success is colorblind. All that he sees is determination and hard work. Any circumstance can be overcome by determination and hard work. I adamantly disagree with my father. I believe that success, first of all, is a relative word. I think that one can dream of success, but when one arrives at the reality, he has lost so much of himself that the passion for success has turned into a mere achievement.

My father has a lifetime of achievements: certificates, honorary degrees, memorials, foundations. If you can think of any outstanding award that is bestowed upon a human being, my father has one somewhere with his name on it. He is one of the most famous attorneys in the United States. His name alone is said to have settled cases without ever going into litigation. And yes, this man, is my father. A man of strong character, and resiliency, of course he has suffered as all men have suffered. But through his sufferings, he emerged a stronger and more determined man than he was before his crisis.

A "trailblazer" in the field of law for African-Americans who follow in his footsteps; a title he publicly denounces. He is called a paramount of an attorney not just for African-Americans, but for all Americans. When asked of his contributions to law, he humbly refers to Thurgood Marshall and says, "Without his contributions, there would be no place for my own." This man is my father.

At this hour, my father is doing what he has done his entire life; searching for the perfect solution to his current problem. This time the issue he faces is greater than any other he has faced in his life. For the issue is not about losing or winning a case. It is not about the prestige of his name, or his crafty courtroom tactics. It is not about awards, certificates, or foundations. It is about an issue he has eluded, and escaped for sixty-eight years. It is time for my father to relinquish his past, and embrace the present. The time has come for my father to face his ultimate nemesis: himself.

• • •

WASHINGTON, D.C., 2008

"As I stand here before you, Lord, my mind reflects upon the past sixty-eight years of my life. And I wonder why destiny has led me to this place, and this time. I am an old man, Lord. If You had given me this task twenty years ago, I would have been more than able to fulfill it. But tonight, what good am I to you?

"I have spent the last year working, and trying to do Your will but I am tired, Lord. I don't know if my old feebly body can hold on until tomorrow.

"But I do know one thing, Jesus. When I leave this courtroom tomorrow, one way or the other, I won't have to worry about ever coming back into another one again in my life. I'm going to have to rest these old bones.

"Well, Lord, I'm almost through praying. My knees hurt so bad I can hardly stand up. Wait a minute, Lord. I've changed my mind. I'm not quite through yet. I wonder how my father would feel if he knew that his only son had grown up to be in this dubious position. My guess would be very afraid. Afraid that I may die in the same manner in which he died. Could You tell him I'm sorry, Lord? Aw, don't worry about it. As old as I feel, I may be able to tell him personally in a day or two.

"Lord, my mother always said that you won't put any more on us than we can handle. How much more do You think I have left, Lord? Give me my strength for one more day, Lord; just like you did Sampson. Please, Lord, just one more day." Solomon continued to stay on his knees as he held the back of the pew in front of him for support. He said, "Amen," to conclude his prayer, and looked up to see an old man entering the rear of the courtroom.

"I'm sorry, sir, this courtroom is not open to the public. You are not

supposed to be in here. This is a top security building. How did you get in here, anyway?" Solomon asked.

"That's the one good thang 'bout bein' a broke-down old man. Nobody ever pay you no 'tention. 'Course they don't pay you no 'tention when you need it, too. I walked up to that do' and walked straight through it, and ain't nobody said one word to me. When you old like this, son, you 'come invisible." The old man laughed.

"I know the feeling of being old," Solomon said.

"Why, you just a baby, Solomon." The old man laughed again.

"You know my name?" Solomon asked.

"Who don't know Solomon Chambers, the modern-day Moses," the old man whispered. "We need you, son. We need you bad."

"What can one man do against the powers that be?" Solomon asked.

"You ain't just one man. You God's man, and like the good book say, if God be fo' you, who can be against you? If God is in you, son, then you the powuh that be. Who can stand against you?" the old man said with his chest stuck out and shoulders pulled back.

"The United States government!" Solomon sighed.

The old man laid his cane to his side, and slid onto one of the benches.

"Let me tell you somethin', son. Sixty-eight years ago I was convicted of robbin' somebody. I was only sixteen years old. They stuck me in a prison with old overgrown men. I was only a boy. Sixteen years old! And they stuck me in that hole and let me rot for sixty-eight long years. I don't have no family. I don't have no friends. I don't have no nothin'!

"They only let me out so I can die, and they won't have to foot the bill. My whole life is gone. Just wasted! You know I done asked God a million times to just let me die. But He wouldn't. As a matter of fact, I ain't never been sick a day in my life until they let me out of jail. And even now, my body ailin' me, but I ain't been down sick. Who say God ain't got no sense of humor, huhn?" The old man laughed.

"Well, thank Jesus you're a free man now," Solomon said.

"Free? What make me free? I ain't got no place to live. I ain't got nobody to love, and I ain't got nobody to love me. I ain't even got nowhere to die. My freedom was taken from me when I was sixteen. I'm an eighty-four-year-old man; the only freedom I got waitin' for me is death. And I can't wait for it to come neitha! I spent my last cent, and probably my last breath comin' all the way up here to talk to you about how important this trial is, Solomon, and I thank God I did."

"I know that this is a high-profile trial. But the bottom line for me is that I see this as yet another trial that I must bring to a just and strategic conclusion."

"Is that why you was prayin' to the Lord? 'cause this is just another trial?"

"I was praying to the Lord because I need him."

"You don't have to worry about the Lord helpin' you, son! You know He gon' do that. You gotta help yo'self!"

Solomon sat up, and tried to stand. It took him a while, but he eventually completed the task. He grabbed his briefcase and thanked the old man for the words of inspiration.

"Thank you, sir, for the words of confidence. I am curious about one thing, sir," Solomon said. "How in the world did you possibly get sixty-eight years in prison for robbery?"

"Hell, I sat in prison for two years befo' they even stuck a charge on me."

"No trial, no conviction, no due process?" Solomon asked.

"Due process? In 1940? In Mississippi? I was happy fuh due life!"

"Did you come all the way up here to tell me that story?"

"No, son, that ain't the story."

"Well, why did you travel all of this way to talk to me?"

"I came to tell you about a man. But befo' I tell you 'bout anybody else, do you know who you are? I ain't talkin' 'bout you bein' no lawyer. Do you know who you is inside? If not, you need to think. Think, son! Before I go any furtha," the old man said.

• • •

DERMA COUNTY, MISSISSIPPI 1935

It was a small county where the colored people made up seventy-two percent of the population. However, the imbalanced number of white people were the beneficiaries of wealth, and power from prior generations. Most of the white people were the children of former slave owners, while most of the colored people were children of former slaves.

The white families had spacious plantation homes, with long driveways that started so far from the house, it was impossible to see the house from the road. There was a social and economic status that was commonplace for mostly all of the white people.

Derma was a rich county, and there were only a few white families who were not wealthy, or financially established. Those few lived in small houses, and worked for the wealthy whites. They also socialized with coloreds, more than whites. The coloreds still called them "Ma'am" and "Sir" and entered through the rear of their homes. They had to respect the color barrier, because the laws of Jim Crow were in full effect.

Jim Crow Laws were the laws formed by Southern states to fight the federal laws incorporated by the Emancipation Proclamation. It kept the spirit of the old South alive.

The colored people lived in large groups in small houses, only a few feet apart. Two or three generations often shared one- or two-bedroom cabins. There were some colored people who moved far into the woods where land had not been claimed to create breathing room for their families. These few families often broke the mold of the poverty-stricken coloreds and became educated and financially stable themselves.

One of those families was the Chambers family, Alexander and Annie Mae Chambers. Alexander was college-educated and worked as a teacher, which was the most prestigious profession for a colored man in Derma County, outside of the clergy. Annie Mae worked on the West Plantation as a maid. She and Alexander were raised together on the West Plantation.

Alexander left Mississippi and went to college up north in Pennsylvania. There he witnessed colored people who were respected and accepted in everyday society. He met a young minister who would later move to Mississippi and hire Annie Mae from the West Plantation. When he returned to Mississippi he could no longer accept the blatant discrimination against colored people without voicing his opinion.

Alexander and Annie were married in 1883 and had their only child, Isaiah, eighteen years later in 1901. Alexander taught Isaiah that he was the equal to any man on this planet: colored, white, rich, or poor. Alexander instilled in his son that the only way to fight discrimination was through education. He made Isaiah believe that an education may not stop some doors from closing in your face, but it can sure open a lot of doors that have always been locked. Annie Mae, on the other hand, taught Isaiah how to be an educated man in Derma County without ending up with his neck at the end of a rope.

In 1911, Alexander's inability to adapt to Mississippi's growing defiance of the advancement of colored people caused him to rally colored families together and speak out against their mistreatment from whites. He told them to save money and buy plenty of land, as he had done, and farm it to support themselves. He told them to learn to depend upon themselves for survival, and not white men.

Alexander explained that coloreds in Derma County outnumbered whites three to one, and they should be a part of the decision-making process. He was met with angry and violent resistance from the white politicians.

On Christmas Eve of that same year, Alexander went out to fetch Christmas dinner for his family, and never returned. Isaiah and one of his friends found his body two days later hanging from a tree in the woods. They dragged his body on a blanket four miles to their house. Ironically, the boy who helped him carry his father's body from the woods was a white boy named John, who lived on the next acre of land with his mother. Isaiah had nothing to give the boy to repay him for his kindness. So he made him a necklace out of the twine used to hang his father. The boy may not have realized where the material to make the necklace came from, but nevertheless, being an impoverished child himself, he was happy to receive it.

Annie Mae was devastated, and never mentally recovered from Alexander's death. Later, her land was confiscated and all that remained for her to support herself and Isaiah was her job working as a maid; a job most colored women sought for employment. But Annie Mae had become accustomed to Alexander's income from farming their land. The land was gone, and the income went with it. Her strength for living was to protect and provide for her son. Isaiah, at the age of ten, suddenly became the man of the house.

Annie Mae raised Isaiah to be a God-fearing man, to believe in God's book, and not man's book. Isaiah, although having been raised by Alexander for only ten short years, was truly his father's son, for he decided to believe in both.

Isaiah grew up to be a strong-willed, but gentle man. His father's murder left an indelible mark on his heart and soul. Like his father, he, too, went up North to attend college. He also witnessed the acceptance of colored people in society, and the conspicuous difference between Negroes in the North, and coloreds in the South.

After college, Isaiah went back to Mississippi to take care of his mother and the land his mother's bossman had purchased for her while he was away. He did not want his mother to lose her land again to the manipulating scoundrels who had stolen their land after his father's death.

He became a schoolteacher and a leader in the colored community. He was respected by coloreds and whites. He had an even temper, and was respectful to every person he met.

In 1934, Annie Mae was stricken with a severe case of pneumonia and died peacefully in her sleep. On her death bed, she revealed to Isaiah certain secrets she had kept hidden from him. The news paralyzed Isaiah's emotions and, after Annie Mae was buried, he became more involved in the church.

A year later Isaiah met a young lady by the name of Orabell Moore in church, where he taught Sunday School. Most people said he had missed his calling to be a preacher. Isaiah started to invite Orabell to church functions, and they fell in love and wanted to be married. He knew that before they discussed marriage any further he had to discuss it with her parents, whom he had never met personally. Mrs. Moore was the sweetest old lady you'd ever find, but Mr. Moore was stubborn, and settled in his ways. He was notorious for carrying a shotgun named Susie and shooting it at people. Though his reputation preceded him, no one ever found proof that he had actually shot someone.

Mr. Moore was a balding, white-haired old man with light skin and sharp, gray eyes. His eyebrows and mustache matched the white color of the hair on the top of his head. He was a small man who spoke fast with a high-pitched voice. He often stuttered, which made it difficult to understand him sometimes. He was in a hurry to get things done; even when there was nothing to do. He wore baggy pants held up by suspenders and corduroy shirts with a white undershirt even in the midst of summer. And he capped it off with a gray and black evening hat. He was a religious man, with the tongue and temper of the devil, who often spoke before he thought.

Mrs. Moore was dark-skinned with long white hair that she kept plaited in one big ball. She wore the long thick skirts that tied around the waist. Her shoes were black with buckles on top. She was the exact opposite of her husband. She was humble and courteous and often resolved issues instead of create them. Mrs. Moore had long patience and tough skin. But when her patience ran out, she could be as vicious as anyone.

The Moores lived back in the woods on land founded and owned by Mr. Moore's father. As most black men in those days, Mr. Moore's father died young, and he had to take over being the man of the house. After he and Mrs. Moore were married they lived together in the house with his mother until her death in 1889. Mr. Moore farmed the land until his body would no longer allow him.

Mr. Moore was proud of his house and his land. His house was huge with a grand porch. The driveway was long like the white folks' driveway and led to the front door of the house. The house sat back far from the road with trees in the yard that hid most of its view until you were almost directly in front of it. There were six stairs leading to the porch making the house appear to be sitting high off of the ground. The porch had two rocking chairs and a porch swing. You entered through the front door and into the living room. The walls were painted with bright colors. The floor was hardwood and shiny. The furniture was antique but in new condition. The kitchen was huge and green. It had a green floor, green cabinets, green walls, and white sink. Upstairs there were five bedrooms. The Moores occupied one, their daughter Orabell and son Stanford occupied one apiece, and the other two were for occasional visitors.

Isaiah had taken notes on all of the habits, beliefs and ideas of the Moore family, and he was going to use them to his advantage when he was courageous enough to go to the Moores and ask for their daughter's hand in marriage.

Mr. Moore refused to allow Orabell to court any man, and she was twenty years old. In that day, an old hag. Isaiah felt that he could convince Mr. Moore to change his mind. He was nervous and perspiring when he walked up the porch stairs to the Moores' home. They looked at him strangely when he stood before them but did not say a word. Finally he found the courage to speak.

"How are you doing this evening, Mr. Moore, Mrs. Moore?" Isaiah asked. "Wonderful evening, isn't it?"

Isaiah was about five feet, ten inches tall, fair-skinned, with dark black curly hair. He had very broad shoulders with light brown eyes, and spoke softly and articulately. He had finally gotten up the nerve to ask for his girlfriend's hand in marriage. A girlfriend whose parents had no idea she was dating.

"It sho' is, son. What might you be payin' us a visit fa tonight?" Mrs. Moore asked.

"Ya look too old to be runnin' around wit my boy, so ya must be comin' fa somethin' else. I hope it ain't fa my gal. Tell me dat ain't why you here, son?" Mr. Moore snapped.

"Well sir, here is the situation. I want to explain this properly so that you won't get the wrong understanding of my intention. I've been a little sweet on your daughter. Yes, sir, I'll admit that to you face to face, like a man, and get that out of the way. I know I am talking a little fast, sir, but that's because I'm nervous...not shady like I'm trying to be crooked, sir, but

nervous...nervous. OK, sir, here it is! I am a schoolhouse teacher, and a Sunday School teacher. I give my tithes every Sunday. Even more than the ten percent the Bible tells us to give. I...I...I...I don't drink, I don't run around chasing after a bunch of different women...I don't have any children running around here either, sir! You can believe that straight from the horse's mouth," Isaiah rambled nervously.

"Hey, boy! You tryin' ta court me, or my daughta?" Mr. Moore asked.

"I'm sorry, sir. I want your daughter, sir," Isaiah said calmly.

"AHA! I knew that's all you wonted!" Mr. Moore screamed.

"No! No, sir! I don't want anything...well, I want Orabell, but that's it!"

"Henry, stop it! You 'bout to scare that boy halfway to death." Mrs. Moore laughed.

"You sure are, sir; you're about to scare that boy halfway to death," Isaiah cried.

"See what you done did, Henry? That boy done fuhgot who he is," Mrs. Moore whispered.

"Mr. Moore, please listen to me, sir. I plan on taking care of your daughter. I have a big house that I built, outside of the West Plantation; I have just as much land as any white man in Derma County. If we ever needed money I could always sell my land so that Orabell would never want for anything," Isaiah said.

"You might not be shady, but you sho' sneaky. You think we don't know 'bout you creepin' round here wit' Orabell?" Mr. Moore asked. "Hadn't been fuh my wife, and me bein' a Christian, me and ol' Susie woulda came and paid you a visit, boy!"

"Mr. Moore, I stand to tell you that yes, I have been courting your daughter, Orabell, but only to church picnics, and revivals. I am not tied up, nor have I ever met anyone named Susie."

"Boy, are you sho' you from Derma County?" Henry asked. "Susie is my shotgun!" Mr. Moore said, erupting in a very loud laugh.

"Oh," Isaiah said, feeling embarrassed.

"Say what you gotta say, son. I gotta get ready fa bed," Mr. Moore mumbled.

"Well, Mr. Moore, all that I have to say is that I love your daughter, and I came over here to ask you for her hand in marriage."

"Son, if I'm right, and I figur' I am, you 'bout twice my daughta age, ain't ya?" Mr. Moore asked.

"No, sir. I am approximately fourteen years older than Orabell, but that doesn't matter."

"The hell it don't!" Mr. Moore shouted. "You done had women, grown women, and my baby ain't had no exper'ince wit' no grown man...ha' she?"

"Oh no, sir! No! No! No! No!"

Mr. Moore looked at Isaiah out of the corner of his eye, as if to let him know that he was watching him to see if he was lying or not.

"We gon' have to pray on it, son. Like my husband say, you near 'bout twice huh age. She don't know nothin' 'bout bein' wit' a man, 'cause I ain't taught huh yet." Mrs. Moore smiled.

"Ma'am, I don't mean any disrespect, but what do you think you can teach her about me, if you don't know me?"

"I don't aim to teach huh nothin' 'bout you, son. She might not even end up wit' you. I'll teach huh what she need ta look out fa in any man. You seem like a good enough fella. You just too old fa my baby. I don't think huh daddy too happy 'bout dis either."

"Hell naw, I ain't happy!"

"Stop all dat cussin', Henry!"

"Well, dis boy could be a crook, a bank robba', anythang! Hell, we don't know!" Mr. Moore said, pointing at Isaiah. "Son, I had my baby when I was almost sixty years old. She is the most preshus thang I got. I can't just let anybody walk up here and take her off."

"I understand what you're saying Mr. Moore," Isaiah said, walking backwards down the stairs. "I think it's about time for me to leave, but 'm happy to have met you and your beautiful wife, and I wish you both a lovely evening."

"Boy, you sho' know how to suck up, don't ya?" Mr. Moore laughed.

"Henry, leave dat boy alone! Thank you fuh stoppin' by, Isiaer," Mrs. Moore said.

"You're welcome," Isaiah answered, nodding his head and holding up his hat.

Isaiah walked off of the porch, and down the driveway to his car. Mr. and Mrs. Moore immediately began to discuss their opinion of his visit.

"I'm gon' tell you sumthin', Cornelia; dat is da fanciest talkin' nigga' I have evuh seen in my life. Talk like a ol' fashion woman. Ain't no man dat good, and he a fool if he think I believe one word of dat mess."

"Well, I believe him. He sound like he was tellin' da troof."

"Lissen at you, ol' woman. A young man come 'round here talkin' fancy to ya, and ya ready to just give ya daughta off to him. Don't dat beat ev'rythang?"

"Say what you wont 'bout his age, but dat's a good man, and ya know it. You just don't wanna give ya baby up."

"You dam' right I don't, and I ain't neitha!"

"You gon' have to one day, if ya wont to, or not."

"Where O'Bell at? Get out here, O'Bell!" Mr. Moore yelled.

Mrs. Moore stood up and yelled through the screen door.

"O'Bell, come see what ya daddy wont!"

Orabell took her time, but eventually she stepped through the screen door to see what her father wanted. Orabell was stunningly beautiful. Dark, smooth skin. Naturally wavy hair, that trickled down her back. An hourglass figure, which displayed every curve on her body, even in the loose-fitting dress she wore. Although she was quite petite in stature, her presence was amazingly noticeable.

"Yes, Daddy?" Orabell asked.

"Ya new beau came ovuh here askin' fuh ya hand in marriage. Nah you wanna tell me what dat's all about?"

"What you talkin' 'bout, Daddy?"

"You know what I'm talkin' 'bout, guhl. Don't talk to me stupid! I'm talkin' 'bout dis grown man comin' up to my house askin' fuh ya hand in marriage. Where you meet dis man? And what make you think I'm gon' let you run off wit' him?"

"Daddy, I ain't runnin' off with nobody. Isaiah and me, we go to church together. He taught me how to read good, and not like how they taught us in school. He's a good man, Daddy, and I love him...I just love him."

"You love him? What you know 'bout love, O'Bell? What make you think dis man gon' make a good husban'?"

"He treat me special. He always askin' how I'm doin', or what can he do to make me happy." Orabell sobbed. "Sometime, Daddy, I wonder why God even let me be born. Think about it, Daddy, what do I have to live for? All I do is take care of you, and Mama. I ain't complainin' 'bout that, but who am I goin' to live for when y'all ain't here no mo'? What's gon' happen to me when I have to live my life all by myself? You ever think about that, Daddy? I don't care how old Isaiah is, he love me for me. And I'm goin' to marry him if you say yes, or if you say no. Now I love you and Mama with all my heart, and I ain't never in my life stepped against nothin' y'all ever told me to do. But I ain't goin' to let this man get away from me," Orabell said with tears in her eyes.

"Cornelia, you ain't gon' say nothin' to dis guhl, talkin' crazy like dis?" Henry shouted.

"It ain't my place to say no mo', Henry, and yours neitha. That guhl know if she love dat man or not. She right, she gon' have to live huh own life. And if she know she love dat man, and dat man love huh

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...