Chapter One Yes, your life is good. But there should be more, so much more. Camelot. Camelot out of her mind. It put her in a strange, dreamy mood, even as she got out at her station and mechanically stopped at the grocery store for dinner.Yes, yes, I know. She had already mailed the card that afternoon, as Aunt Tessie most certainly would have guessed. Tessie simply wanted to hear about Julie's social life, the glamorous New York niece living an oh-so-glamorous existence in the city. Not that Julie had ever uttered a single word to reinforce the notion of such a life. That was not necessary -- Aunts Tessie and Fran had already filled in the blanks on their own. And they had indeed created a wondrous life for their niece.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

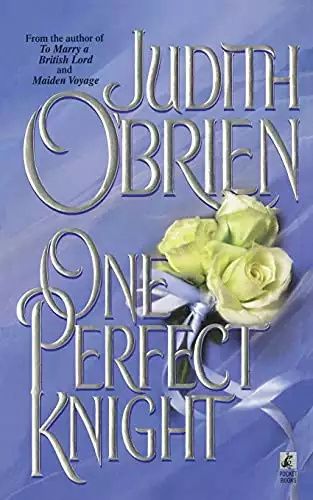

One Perfect Knight

Judith O'Brien

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved

Close