- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

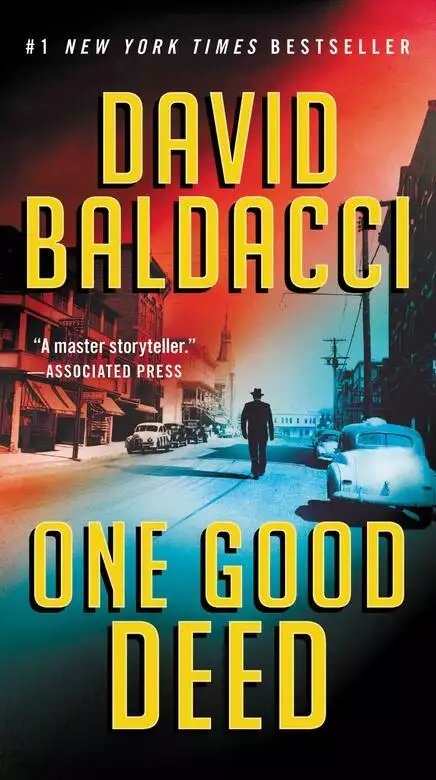

The number one New York Times best-selling author David Baldacci introduces an unforgettable new character: Archer, a straight-talking former World War II soldier fresh out of prison for a crime he didn't commit.

It's 1949. When war veteran Aloysius Archer is released from Carderock Prison, he is sent to Poca City on parole with a short list of do's and a much longer list of don'ts: do report regularly to his parole officer, don't go to bars, certainly don't drink alcohol, do get a job — and don't ever associate with loose women.

The small town quickly proves more complicated and dangerous than Archer's years serving in the war or his time in jail. Within a single night, his search for gainful employment — and a stiff drink — leads him to a local bar, where he is hired for what seems like a simple job: to collect a debt owed to a powerful local businessman, Hank Pittleman.

Soon Archer discovers that recovering the debt won't be so easy. The indebted man has a furious grudge against Hank and refuses to pay; Hank's clever mistress has her own designs on Archer; and both Hank and Archer's stern parole officer, Miss Crabtree, are keeping a sharp eye on him.

When a murder takes place right under Archer's nose, police suspicions rise against the ex-convict, and Archer realizes that the crime could send him right back to prison...if he doesn't use every skill in his arsenal to track down the real killer.

Release date: July 23, 2019

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

One Good Deed

David Baldacci

IT WAS A GOOD DAY to be free of prison.

The mechanical whoosh and greasy smell of the opening bus doors greeted Aloysius Archer, as he breathed free air for the first time in a while. He wore a threadbare single-breasted brown Victory suit with peak lapels that he’d bought from the Sears, Roebuck catalogue before heading off to war. The jacket was shorter than normal and there were no pleats or cuffs to the pants because that all took up more material than the war would allow; there was no belt for the same reason. A string tie, a fraying, wrinkled white shirt, and scuffed lace-up size twelve plain Oxford shoes completed the only wardrobe he owned. Small clouds of dust rose off his footwear as he trudged to the bus. His pointed chocolate brown fedora with the dented crown had a loop of faded burgundy silk around it. He’d bought the hat after coming back from the war. One of the few times he’d splurged on anything. But a global victory over evil had seemed to warrant it.

These were the clothes he’d worn to prison. And now he was leaving in them. He comically lamented that in all this time, the good folks of the correctional world had not seen fit to clean or even press them. And his hat held stains that he hadn’t brought with him to incarceration. Yet a man couldn’t go around without a hat.

The pants hung loosely around his waist, a waist grown slimmer and harder while he’d been locked up. He was fully twenty-five pounds heavier than when he’d gone into prison, but the extra weight was all muscle, grafted onto his arms, shoulders, chest, back, and legs, like thickened vines on a mature tree. In his socks he was exactly six feet one and a quarter. The Army had measured him years before. They were quite adept at calculating height. Though they had too frequently failed to supply him with enough ammunition for his M1 rifle or food for his belly, while he and his fellow soldiers were trying to free large patches of the world from an oddball collection of deranged men.

The prison had a rudimentary gym, of which he’d taken full advantage. It wasn’t just to build up his body. When he was pumping weights or running or working his gut, it allowed him to forget for a precious hour or two that he was squirreled away in a cage with felonious men. The prison also held a book depository teeming with tattered, coverless books that sported missing pages at inopportune times, but they were precious to him nonetheless. His favorites had been Westerns where the man got the gal. And detective novels, where the man got the gal and also caught the bad guy. Which he supposed was a funny sort of way for a prisoner to be entertained. Yet he liked the puzzle component of the mystery novels. He tried to solve them before he got to the end, and found that as time went on, he had happened upon the correct solution more often than not.

The jail grub he had pretty much done without. What wasn’t spoiled or wormy held no discernible taste to persuade him to ingest it. He’d gotten by on a variety of fruits picked from a nearby orchard, vegetables harvested from the small garden inside the prison walls, and the occasional piece of fried chicken or soft bread and clots of warm apple fritters that arrived at the prison in mysterious ways. Some said they were dropped off by compassionate ladies either looking to do good, or else hoping for a husband in three to five years. The rest of his time was spent either busting big rocks into smaller ones using sledgehammers, collecting trash along the side of the roads, only to see it back the next day, or else digging ditches to nowhere fast because a man with a double-barreled shotgun, sunglasses, a wide-brimmed hat, and a stone-cold stare told him that was all he was good for.

He was not yet thirty, was never married, and had no children, but one glance in the mirror showed a man who seemed older, his skin baked brown by the sun and further aged by being behind bars the rest of the time. A world war coupled with the brutal experience of losing one’s liberty had left their indelible marks on him. These two experiences had successfully robbed him of the remainder of his youth but hardened him in ways that might at some point work out in his favor.

His hair had been long going into prison. On the first day they had cut it Army short. Then he’d tried to grow a beard. They’d shaved that off, too. They said something about lice and hiding places for contraband.

He vowed never to cut his hair again, or at least to go as long as possible without doing so. It was a small thing, to be sure. He had started out life concentrated only on achieving large goals. Now he was focused on just getting by. The impossibly difficult ambitions had been driven from him. On the other hand, the mundane seemed reasonably doable for Archer.

He ducked his head and swept off his fedora to avoid colliding with the ceiling of the rickety vehicle. The bus doors closed with a hiss and a thud, and he walked down the center aisle, a suddenly free man looking for unencumbered space. The rocking bus was surprisingly full. Well, perhaps not surprisingly. He assumed this mode of transport was the only way to get around. This was not the sort of land where they built airfields or train depots. And those black ribbons of state highways never seemed to get rolled out in these places. It was the sort of area where folks did not own a vehicle that could travel more than fifty miles at any given time. Nor did the folks driving said vehicles ever want to go that far anyway. They might fall off the edge of the earth.

The other passengers looked as bedraggled as he, perhaps more so. Maybe they’d been behind their own sorts of bars that day, while he was leaving his. They were all dressed in prewar clothes or close to it, with dirty nails, raw eyes, hungry looks, and not even a glimmer of hope in the bunch. That surprised him, since they were now a few years removed from a wondrous global victory and things were settling down. But then again, victory did not mean that prosperity had suddenly rained down upon all parts of the country. Like anything else, some fared better than others. It seemed he was currently riding with the “others.”

They all stared up at him with fear, or suspicion, or sometimes both running seamlessly together. He saw not one friendly expression in the crowd. Perhaps humankind had changed while he’d been away. Or then again, maybe it was the same as it’d always been. He couldn’t tell just yet. He hadn’t gotten his land legs back.

Archer spotted an empty seat next to an older man in threadbare overalls over a stained undershirt, a stubby straw hat perched in his lap, brogans the size of babies on his feet, and a large canvas bag clutched in one callused hand. He had watched Archer, bug-eyed, for the whole time it took him to reach his seat. An instant before Archer’s bottom hit the stained fabric of the chair, the other man let himself go wide, splaying out like a pot boiling over, forcing Archer to ride on the edge and uncomfortably so.

Still, he didn’t mind. While his prison cell had been bigger than the space he was now occupying, he had shared it with four other men, and not a single one of them was going anywhere.

But now, now I’m going somewhere.

“Joint stop?”

“What’s that?” asked Archer, eyeballing the man looking at him now. His seatmate’s hair was going white, and his mustache and beard had already gone all the way there.

“You got on at the prison stop.”

“Did I now?”

“Yeah you did. How long did you do in the can?”

Archer turned away and looked out the windshield into the painful glare of sunshine and the vast sky over the broad plains ahead that was unblemished by a single cloud.

“Long enough. Hey, you don’t happen to have a smoke I can bum?”

“You can’t really borrow a smoke, now can you? And you can’t smoke on here anyways.”

“The hell you say.”

The man pointed to a handwritten sign on cardboard hanging overhead that said this very thing.

More rules.

Archer shook his head. “I’ve smoked on a train, on a Navy ship. And in a damn church. My old man smoked in the waiting room when I was being born, so they told me. And he said my mom had a Pall Mall in her mouth when I came out. What’s the deal here, friend?”

“They’ve had trouble before, see?”

“Like what?”

“Like some knucklehead fell asleep smoking and caught a whole dang bus on fire.”

“Right, ruin it for everybody else.”

“Ain’t good for you anyway, I believe,” said the man.

“Most things not good for me I enjoy every now and again.”

“What’d you do to get locked up? Kill a man?”

Archer shook his head. “Never killed anybody.”

“Guess they all say that.”

“Guess they do.”

“Guess you were innocent.”

“No, I did it,” admitted Archer.

“Did what?”

“Killed a man.”

“Why?”

“He was asking too many questions of me.”

But Archer smiled, so the man didn’t appear too alarmed at the veiled threat.

“Where you headed?”

“Somewhere that’s not here,” said Archer. He took off his jacket, carefully folded it, and laid it on his lap with his hat on top.

“Is all you got the clothes on your back?”

“All I got.”

“What’s your ticket say?”

Archer dug into his pocket and pulled it out.

It was eighty and dry outside and about a hundred inside the bus, even with the windows half-down. The created breeze was like oven heat and the mingled odors were…peculiar. And yet Archer didn’t really sweat, not anymore. Prison had been far hotter, far more…peculiar. His pores and sense of smell had apparently recalibrated.

“Poca City,” he read off the flimsy ticket.

“Never been there, but I hear it’s growing like gangbusters. Used to be the boondocks. But then it went from cattle pasture to a real town. People coming out this way after the war, you see.”

“And what do they do once they get there?”

“Anything they can, brother, to make ends meet.”

“Sounds like a plan good as another.”

The older man studied him. “Were you in the war? You look like you were.”

“I was.”

“Seen a lot of the world, I bet?”

“I have. Not always places I wanted to be.”

“I been outta this state exactly one time. Went to Texas to buy some cattle.”

“Never been to Texas.”

“Hey, you been to New York City?”

“Yes, I have.”

The man sat up straighter. “You have?”

Archer casually nodded his head. “Passed through there on account of the war. Seen the Statue of Liberty. Been to the top of the Empire State Building. Rode the rides over at Coney Island. Even seen some Rockettes walking down the street in their getups and all.”

The man licked his lips. “Tell me something. Are their legs like they say, friend?”

“Better. Gams like Betty Grable and faces like Lana Turner.”

“Damn, what else?” he asked eagerly.

“Had a box lunch in the middle of Central Park. Sat on a blanket with a honey worked at Macy’s department store. We drank sodas and then she slipped out a flask from the top of her stocking. What was in there? Well, it was better’n grape soda, I can tell you that. We had a nice day. And a better night.”

The man scratched his cheek. “So, what are you doing all the way out here then?”

“Life has a crazy path sometimes. And like you said, folks heading this way after the war.”

The man, evidently intrigued now by his companion, sat up straighter, allowing Archer more purchase on his seat.

“And the war was a long time ago, or seems it anyway,” said Archer, stretching out. “But you got one life, right? Less somebody’s been lying to me.”

“Hold on now, Church says we get two lives. One now, one after we’re dead. Eternal.”

“Don’t think that’s in the cards for me.”

“Man never knows.”

“Oh, I think I know.”

Archer tipped his head back, closed his eyes, and grabbed his first bit of shut-eye as a free man in a long time.

Chapter 2

ARCHER GOT OFF at Poca City seven hours later and too many stops in between to remember. People had gotten on and people had gotten off. They’d had a dinner and bathroom break at a roadside diner with an outhouse in the back, both of which looked only a stiff breeze away from falling over. It was nearly eight in the evening now. He stood there as the bus and the rube with too many queries and the remaining nervous folks clutching all they owned sped off into the night chasing pots of gold along dusty roads with nary a helpful leprechaun in sight.

Good riddance to them all, thought Archer. And then, a second later, his more charitable consideration was, Well, good luck to them.

We all needed luck now and then, was his firm belief. And maybe right now he needed it more than most. The point was, would he get it?

Or will I have to make my own damn luck? And hope for no bad luck as a chaser?

He put on his hat and then his jacket and looked around. He was in Poca City because the DOP said it was here he had to serve his parole. He dragged out the pages he’d been given. In fat, bold typeface at the top of the page was “Department of Prisons,” or the DOP. Below that was a long list of “don’ts” and a far shorter list of “dos.” These rules would govern his life for the next three years. Though he was free, it was a liberty with lassoes attached, with so-called legal conditions that he mostly could make neither head nor tail of. Who knew prison could stick to you, like running into a spider’s web in the morning, flailing about, just wanting to be free of the tendrils, while alarmed that a poisonous thing was coming for you.

Archer had been released from prison well before he served his full sentence due to time off for good behavior and also for passing muster at his first parole board meeting. He had ventured into the little stuffy room that held a flimsy table with three chairs behind and one chair in front and him not knowing what to expect. Two burly prison guards had accompanied him to this meeting. He had been dressed in his prison duds, which seemed to shriek “guilt” and “continued danger” from each pore of the sweat-stained fabric.

Behind the table were three people, two men and one woman. The men were short and stout and freely perspiring in the closeness of the room. They looked self-important and bored as they greedily puffed on their fat cigars. The woman, who sat in the middle of this little band of freedom givers or takers, was tall and matronly with an elaborate hat on which a fabric bird clung to one side, and with a dead fox around her blocky shoulders.

Archer had instantly seized on her as the real power, and thus had focused all of his attention there. His contriteness was genuine, his remorse complete. He stared into her large, brown eyes and said his piece with heartfelt emphasis contained in each word, until he saw quivering at the corners of those eyes, the false bird and fox start to shake. When he’d finished and then answered all her questions, the consultation among the board was swift and in his favor as the men quickly capitulated to the woman’s magisterial decree.

And that had been the price of freedom, which he had gladly paid.

The Derby Hotel was where the DOP said it would be. Point for those folks, grudgingly. Its architecture reminded him of places he’d seen in Germany. That did not sit particularly well with him. Archer hadn’t fought all those years to come home and see any elements of the vanquished settled here. He trudged across the macadam, the collected heat of the day wicking up into his long feet. Though the sky was now dark, it was still cloudless and clear. The air was so dry he felt his skin try to pull back into itself. Archer also thought he saw dust exhaled along with breath. A pair of old, withered men were bent over a checkerboard table incongruously perched in the shadow of a large fountain. The thing was built principally of gray-and-white marble with naked, fat cherubs suspended in the middle holding harps and flutes, and not a drop of water coming out of the myriad spouts.

With furtive glances, the old men watched him coming. Archer shuffled along rather than walked. For long distances in prison, meaning longer than a walk to the john, you had your feet shackled. And so, you shuffled along. It was demeaning, to be sure, and that was the whole purpose behind it. Archer meant to rid himself of the motion, but it was easier said than done.

He could feel their gazes tracking him, like silent parasites sucking the life out of him at a distance, him in his cheap, wrinkled clothes with his awkward gait.

Prison stop. Look out, gents, ex-con shuffling on by.

He nodded to them as he and his filthy shoes grew closer to the cherubic fountain and the bent checker-playing men. Neither nodded in return. Poca City apparently was not that sort of place.

He reached the harder pavement in front of the hotel, swung the front door wide and let it bang shut behind him. He crossed the floor, the plush carpet sucking him in, and tapped a bell set on the front desk. As its ringing died down, he gazed at a sign on the wall promising shined shoes fast for a good rate. That and a shave and a haircut, and a masculine aftershave included.

A middle-aged man with a chrome dome and wearing a not overly clean white shirt with a gray vest over it and faded corduroy trousers came out from behind a frayed burgundy curtain to greet him. His sleeves were rolled up and his forearms were about as hairy as any Archer had ever seen. It was like fat, fuzzy caterpillars had colonized there. His nails could have used a scrubbing, and he seemed to have the same coating of dust as Archer.

“Yes?” he said, running an appraising glance over Archer and clearly coming away not in any way, shape, or form satisfied.

“Need a room.”

“Figgered that. Rates on the wall right there. You okay with that?”

“Do I have a choice?”

The man gave him a look while Archer felt for the wrinkled dollars in his pocket.

“Three nights.”

The man put out his hand and Archer passed him the money. He put it in the till and swung a stiff ledger around.

“Please sign, complete with a current address.”

“Do I have to?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“It’s the law.”

The law seemed to be everywhere these days.

Archer reluctantly took up the chubby pen the man handed him. “What’s the address of this place?”

“Why?”

“Because that’s my current address, is why.”

The man harrumphed and told him.

Archer dutifully wrote it down and signed his name in a flourish of cursive.

The man eyed the signature upside down. “That’s really your name?”

“Why? You mostly get Smiths and Jones here with ladies on their arms for short stays?”

“Hey, fella, this ain’t that kind of a place.”

“Yeah, I know, you’re all class. Like the naked babies set in marble outside.”

“Look it, where you from?” said the man, a scowl now crowding his face.

“Here and there. Now, here.”

The man slid open a drawer and pulled out a fat, brass key.

“Number 610. Top floor. Elevator’s that way.” He pointed to his left.

“Stairs?”

“Same way.”

As Archer started off, the man said, “Wait, don’t you have no bags?”

“Wearing ’em instead of carrying ’em,” replied Archer over his shoulder.

He took the stairs, not the elevator. Elevators were really little prison cells, was his opinion. And maybe the doors wouldn’t open when he wanted them to. What then?

One thing prison took away from you, hard and clear, was simple trust.

He unlocked the door to 610 and surveyed it, taking his time. He had all the time in the world now. After counting every minute of every hour of every day for the last few years, he no longer had to. But still, it was a tough habit to break. He figured he might actually miss it.

He checked the bed: flimsy, squeaky. His in prison had been concrete masquerading as a mattress, so this was just fine. He opened a drawer and saw the Gideon Bible there along with stationery and a ballpoint pen.

Well, Jesus and letter writing are covered.

He took off his jacket and hung it on a peg, placing his hat on top of it. He slipped out his folding money. He laid the bills out precisely on the bed, divided by denomination. There was not much there after he’d laid out the dough for the room. The DOP had been stingy, but in an effective way.

He would have to work to survive. This would keep him from mischief. He wasn’t guessing about this.

Archer took out his parole papers. It was right there in the very first paragraph.

Gainful employment will keep you from returning to your wayward ways, and thus to prison. DO NOT FORGET THIS.

He continued running his eye down the page.

First meeting was tomorrow morning at nine a.m. sharp. At the Poca City Courts and Municipality Building. That was a long name, and it somehow stoked fear in Archer. Of rules and regulations and too many things for him to contemplate readily. Or adhere to consistently.

Ernestine Crabtree was her name. His parole officer.

Ernestine Crabtree. It sounded like quite a fine name.

For a parole officer.

He opened his window for one reason only. His window had never opened in prison. He sucked in the hot, dry air and surveyed Poca City. Poca City looked back at him without a lick of interest. Archer wondered if that would always be the case no matter where he went.

He lay back on the bed. But his Elgin wristwatch told him it was too early to go to bed. Probably too late to get a drink, though number 14 on his DOP don’t list was no bars and no drink. Number 15 was no women. So was number 16, at least in a way, though it more specifically referred to no “loose” women. The DOP probably had amassed a vast collection of statistics that clearly showed why the confluence of parolees and alcohol in close proximity to others drinking likewise was not a good thing. And when you threw in women, and more to the point, loose women, an apocalypse was the only likely outcome.

Of course, right now, he dearly wished for a libation of risky proportion.

Archer put on his jacket and his hat, scooped up his cash, and went in search of one.

And maybe the loose women, too.

A man in his position could not afford to be choosy. Or withholding of his desires.

On his first day of freedom he deemed life just too damn short for that.

Chapter 3

HE FOUND IT only a short distance from the hotel. Not on the main drag of Poca City, but down a side street that was only half the length of the one he’d left—but it was far more interesting, at least to Archer’s mind.

If the main street was for checker playing and marble musical babies, this was where the adults got their jollies. And Archer had always been a fan of the underdog with weaknesses of the flesh, considering how often he fell on that side of the ledger.

The marquee was neon blue and green with a smattering of sputtering red. He hadn’t seen the likes of such since New York City, where it had been ubiquitous. Yet he hadn’t expected a smidge of it in Poca City.

THE CAT’S MEOW.

That’s what the neon spelled out along with the outline of a feline in full, luxurious stretch that seemed erotic in nature. To Archer, Poca City was getting more interesting by the minute.

He pushed open the red door and walked in.

The first thing he noted was the floor. Planked and nailed and slimed with the slop of what they’d been serving here since the place opened, he reckoned. His one shoe stuck a bit, and then so did the other. Archer compensated by picking up the force of his steps.

The next thing of note was the crowd, or the size of it anyway. He didn’t know the population of the town, but if it had any more people than were in here, it might qualify as a metropolis.

The bar nearly ran the length of one wall. And like on the bows of old ships, sculpted into the corner support posts of the bar were the heads and exposed bosoms of women—he supposed loose ones. And every stool had a butt firmly planted on it. Against one wall fiddle and guitar players plucked and strummed, while one gal was singing for all she was worth. She had red curly hair, a pink, freckled face, and slim hips with stiff dungarees on over them. Her notes seemed to hit the ceiling so hard they ricocheted off with the force of combat shrapnel.

Behind the bar was a wall of shelves holding every type of bottled liquor Archer had ever seen and then some, by a considerable margin. He reckoned a man could live his whole life here and never grow thirsty, so long as the coin of the realm kept up.

Indeed, happening on this place after being behind bars this morning and enduring a long, dusty bus ride and encountering less than friendly citizens hereabouts, Archer considered he might be in a dream. With three years of probation to endure, he felt like a large fish with a hook in its mouth. He could be yanked back at any moment, and that lent force to a man’s whims. Thus, he decided to take full advantage while he could.

Sidling up to the bar, he wedged in between what seemed a colossus of a farmer with a rowdy beard and hands the width of Archer’s head, and a short, thick, late-fifties-something, slick-haired banker type in a creamy white three-piece suit far nicer than Archer’s. He also had a knotted blue-and-white-striped tie, with reptile leather two-tone shoes on his feet, a fully realized smirk in his eye, and a woman less than half his age on his arm. Resting on the bar in front of the man was a flat-crowned Panama hat with a yellow band of silk.

Archer caught the bartender’s attention and held up two horizontally stacked fingers and tacked on the words “Bourbon, straight up.”

The gent, old, spent, and thin as a strand of rope, nodded, retrieved the liquor from the vast stacks, poured it neat into a short glass, and held it out with one hand, while the other presented itself palm up for payment. It was a practiced motion that a man like Archer could appreciate.

“How much you charging for that?” he asked.

“Fifty cents for two fingers, take it or leave it, son.”

“What’s the bourbon again, pops?”

“Only one bourbon in these parts, young feller. Rebel Yell. Wheat, not rye. You don’t like Rebel, you best pick another type of alcohol or another part of the state. Give me an answer, ’cause I ain’t getting any younger and I got thirsty folks with folding money want my attention.”

“Rebel sounds fine to me.”

He passed over the two quarters and settled his elbows on the bar with the short glass cupped in both hands. He hadn’t had a drink in a while. He’d banged one back the day before prison, just for good luck, so he reckoned it was a certain symmetry to have one the day he left prison. He was into balance if nothing else these days. And moderation, too, until it proved inconvenient, which it very often did to a man like him.

The banker eyed Archer, while his lady ran her tongue over full lips painted as warm a red as a sky hosting a setting sun.

“You’re not from here,” said the banker. His silver hair was cut, combed, and styled with the precision available only to a man who had the dollars and leisure time for such tasks. His face was as flabby as the rest of him, and also tanned and creased with lines in a way that women might or might not find attractive. For such a man, the thickness of his wallet and not the fitness of his torso was his main and perhaps only aphrodisiac for the ladies.

“I know I’m not,” replied Archer, sipping the Rebel and letting it go down slow, the only way to drink bourbon, or so his granddad had informed him. And not only informed but demonstrated on more than one occasion. He tipped his hat back, turned around, bony elbows on the bar, his long torso angled off it, and studied the banker, then flitted his gaze to the lady.

The banker’s smirk broadened—he was reading Archer’s mind, no doubt.

“I like this town,” said the banker. “And everything in it.”

He patted the lady’s behind and then his hand remained perched there. She seemed not to mind or else had grown accustomed to this fondling, or both. As the man’s fingers stroked her, she took a moment to powder her nose while looking in a mirror attached to a shiny compact. The lady next shook out a tube of lipstick from her clutch purse and repainted her mouth before once more taking up what looked to be a murky martini with three fat olives lurking mostly below the surface, like gators in a bog.

“Been in Poca City long, have you?” inquired Archer.

“Long enough to see what’s good and what needs changing. And then changing it.”

He closed his mouth and eyed Archer from under tilted tufts of eyebrow.

“You gonna keep me in suspense?” said Archer finally.

The banker laughed and swallowed some of his whiskey. His eyes flickered just a bit as the drink went down, like wobbly lights in a storm.

Archer’s mouth eased into a smile at this weakness, but the man didn’t seem to notice. Or care.

“Poca’s growing. This used to be just cattle land. And farming. Now that’s changing. Business and money coming in. Not too much riffraff.”

“How do you decide about riffraff? See, I might fall into that category and then where do we go with this happy conversation?”

The lady laughed at this, but the banker did not. She shut her mouth and sipped her bog.

The banker intoned, “Fact is, a man can make money here if he’s willing to work. With the war over, we have winners and losers. I aim to make certain Poca falls on the winner’s side of the ledger. Se

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...