- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

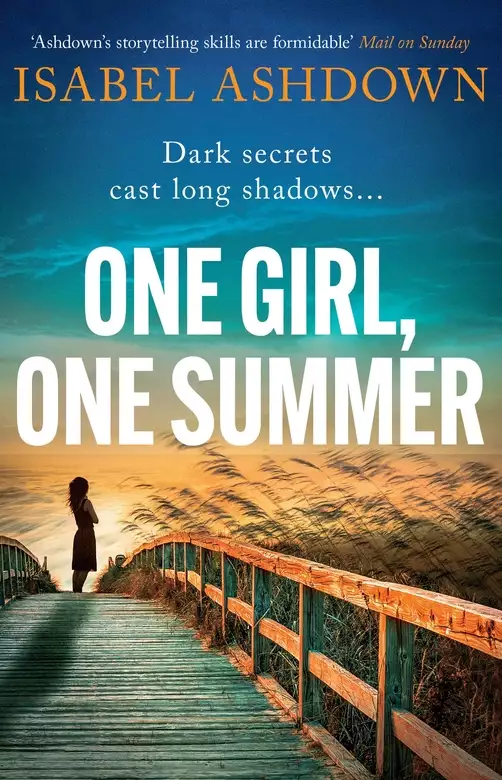

Dark secrets cast long shadows...

On a peaceful hilltop campsite in the heat of summer, a private plane crash-lands. Several are killed, and many more lives are shattered - including those of the Gale family who own the site. For single parent Cathy Gale, her everyday struggles are eclipsed by the tragedy, as her boy Albie is one of the victims. He hangs onto life, while 18-year-old sister Nell, who was meant to be looking after him, is overcome with guilt.

As DS Ali Samson leads the investigation, locals are scandalised to learn that the amnesiac pilot has plans to stay on in the community. As dark secrets come to light, teenager Nell goes into freefall. What is it she's so desperate to conceal? And exactly who is the Unknown Pilot?

If you loved HOMECOMING by Isabel Ashdown, return to the beautiful coastal town of Highcap, Dorset, a community hiding many secrets.

Release date: July 1, 2024

Publisher: Orion

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

One Girl, One Summer

Isabel Ashdown

Flashbulb memory. This was the topic, a half-remembered chapter from some psychology textbook, snaking through Nell Gale’s mind as she finally reached the dawn-bright summit of Highcap after the long trek from town. A random recollection of facts and revision unlikely ever to be used again, now her studies were over. She leant against the stone marker, her gaze fixed on the shimmering line of the ocean as she zoned out all feeling, mastering her breathing, her thoughts.

Her recollection of the night before, indistinct as it was, seemed to Nell as vague and unsettling as a hazy nightmare half-vanished the morning after, and she prayed that that might be the case. Because memory was a strange thing, an unreliable thing, wasn’t it? And, if she worked hard enough at reshaping the small parts she did recall, perhaps she might convince herself that last night never happened at all.

That she’d never been there, off her face on vodka, stumbling down that foul-smelling alleyway, out of control.

She checked her watch, her stomach turning at the sight of its scratched glass face and the unmistakable strands of dark hair caught in the strap. Not hers.

Almost without thought, she tore the watch from her wrist, digging her fingers deep into the soil at the edge of the marker, to bury both it and the night before beneath the dry earth of Highcap summit. With a rush of cold nausea, she bent over her knees and vomited at the edge of a gorse bush, grateful that, in this moment at least, there was no one around to witness her shame.

Sliding down against the stone, Nell wept a little, and rested awhile. Far below, the main road meandered like a faultline along one side of the campsite, while, to the other, the glistening sea swept the Dorset coastline, a wild blue brushstroke. At this early hour, only a few tiny washbag-clutching figures moved about the grassy plain below, which, from Nell’s vantage point, appeared strangely 2-D, made all the more surreal by the recent addition of a giant gold rabbit, positioned on the main path to welcome newcomers to the campsite. Auntie Suzie had officially unveiled ‘Goldie’ at the start of the season, and Mum, happy enough to drink her sister-in-law’s prosecco, had nudged Nell and sniggered and whispered that she thought a better name might be ‘Auntie Suzie’s Child-Scaring Rabbit’. Why did her mum always have to be such a bitch?

Nell tried to push away thoughts of her mother and rose to her feet again, taking in the rolling green landscape that stretched for miles. This was the one thing she would miss, if she ever got away from this place. This view; this air.

If she ever got away? Because that had always been the plan, hadn’t it? To get away. She shook her head at the stupidity of the idea, an idea encouraged by the adults in her life, right up until the moment when her mother had pulled the rug from under her. Why? Nell had demanded when they’d argued again yesterday. With A levels and the endless incarceration of school finally behind her, this was meant to be the summer to beat all others, a summer of adventure and independence. Why would her mum, who herself had travelled and experienced all the things Nell wanted for herself, deny her this? Who was she to withhold the money Grandad had gifted her?

Down in the campsite, a few more early risers emerged from their mobile homes to potter about like Playmobil people. Despite her desperation to escape the place, Nell could never completely shake her feeling of pride – or perhaps it was belonging – at being part of the Gale family, regardless of the occasional local resentments the name invoked. Theirs was one of the oldest names in Highcap’s graveyard, and the Golden Rabbit campsite was built on land owned by their family going back generations, land that was once worthless, turned into a goldmine by her grandfather’s father.

It was still one of the prettier sites around Highcap – one of the smallest, with fewer static homes and a large expanse of grassland given over to hikers’ tents and passing tourers. Right now, the on-site farm shop, with its cheery bunting and candy-stripe awning, had not yet opened its doors for the day, and with at least twenty plots still unoccupied, you’d be forgiven for thinking the summer season hadn’t yet got underway.

As Nell contemplated her descent, the wind rose, whipping through her red curls and causing her oversized shirt to flap like a sail. She grew aware of a small aeroplane approaching from out over the water, the distant burr of its engine like the pleasing hum of a lawnmower on a lazy Sunday morning. How ordinary she must appear to the approaching pilot, she thought, high overhead in the cloudless sky. How carefree. Ha, if they only knew the half of it.

In a sudden change of direction, the plane swooped away again, veering off along the coast and further out above the shimmering water. Nell wished she were in that small plane; she wished she were anywhere but here, nearly nineteen and still at home, while the best of her friends headed off to uni and the worst of them stuck around, seemingly happy enough to stay in Highcap forever, having babies and marrying the boy next door.

She checked the time on her phone. It wasn’t yet 7 a.m., and, other than that circling plane, all was still. The main road below had been empty for at least the past ten minutes. But now, a vehicle appeared, and, as it turned in through the campsite gates below, she recognised it as her mother’s battered orange Citroën. Nell traced its journey along the well-tended path, past Goldie and the farm shop and the various communal blocks, until it stopped near the children’s playground in a parking bay reserved for staff.

‘Shit.’ At once, Nell remembered she was meant to be home with Albie for Mum’s early cleaning shift, a concession she’d grudgingly agreed to last night before she’d slammed the front door on their argument.

‘Just get him to tennis practice at eight,’ Mum had called after her with a dismissive flap of her fag hand, one foot inside the kitchen, one out the back door. ‘Then you can do whatever you like.’

Ha! ‘Anything except go travelling?’ Nell had yelled back, shrill with rage. But she knew her brother had his under-fourteen championships coming up next month, and she knew he couldn’t afford to miss his training, and so, for Albie’s sake alone, she’d agreed.

‘Shit-shit-shit,’ she repeated in a low murmur, setting off towards the coastal path with greater purpose now, one eye on the scene below. If she hurried, she could drive Albie to tennis in Mum’s car and still get it back in time for the end of her shift.

Nell’s distant view was clear enough to see the passenger door of the car fly open and Albie tumble out in his yellow beach-camp sweatshirt, already in a run, board wedged beneath his arm as he headed for the skate ramps. Mum gave a hasty little wave in his direction and turned away. With chaotic red hair bursting like springs from her headscarf, she hurried off to the showers with her cleaning trolley, mobile phone pressed to her ear. Simultaneously, Nell’s phone rang in the palm of her hand, and she muted it with a tut and shoved it into the back pocket of her baggy trousers.

Across the camp lawns, a bare-chested young man emerged from a small blue tent, his white sneakers brightly contrasting with the faded red of his cap and scruffy cut-off denim shorts. He pushed his elbows back in a leisurely stretch and slung a towel over his tanned shoulder. Nell wished he’d look up in her direction, and she wondered how old he was, whether he was a good person.

Without turning, he sauntered over the grass, making for the shower block, and Nell continued downwards, picking up pace as an uneasy feeling settled in the pit of her stomach. She was now entirely visible to anyone who might glance up from the campsite below, but she had the strongest sense that if they did, they wouldn’t see her; that she had somehow become invisible to all the world. She felt like a ghost, as though the events of the night before had in fact killed her, banished her to the outside.

Overhead, the hum of the aircraft repeated, shaking her back to the present. This time it felt closer, and Nell’s hair whipped wilder as the circling plane cast a slow-moving shadow over the rolling hills.

In the distant play area, Albie scaled the highest skate ramp, and Nell, desperate to be seen by her brother, raised her arms high in a double wave, like a stranded explorer sending out an SOS. Albie halted; legs planted wide in a familiar stance of concentration. Her heart lifted. It was how he stood on the tennis court: alert, bouncing the racket head off the palm of his hand, waiting for the serve. After just a beat, he waved back, madly, beckoning her down, his little dancing hop conveying how happy he was to spot his big sister high up on the hill.

Again Nell’s phone rang, insistent, and, weakened by the sight of Albie’s daisy-bright dance, she brought the ringing phone to her ear.

‘Mum?’ she answered, raising her voice against the intensifying roar of the plane. The ground beneath her grew dark and her own shadow disappeared.

Over on the main road, Auntie Suzie’s white Land Rover was now turning in through the gate, with Uncle Elliot’s head craning from the open window, his face turned skyward. Nell’s heart pounded as the shadow of the plane grew wider and darker and the deep thrum of its engine drowned out all other sound. At the shower blocks, Mum stepped out onto the path and squinted into the sky overhead.

‘Mum?’ Nell spoke into the phone, but her voice was muffled beneath the roar.

Albie was still balanced at the top of the skate ramp, waiting for his sister, or perhaps transfixed by the spectacle himself, and for long seconds, Nell could not move. Inert, she was gripped by the strongest sensation of drifting high above herself, high above them all, helpless with certainty that another bad thing was about to happen.

‘Nell?’ Mum’s voice echoed through the handset, but later Nell wouldn’t be sure whether she’d imagined it, because the next thing she heard was the bone-crunching explosion of metal and glass, as the campsite below her disappeared behind a vast cloud of billowing grey dust. Caravans and tents and a child’s bright red skateboard toppled toy-like across the green coastal plain, and Auntie Suzie’s Land Rover ploughed headlong into the giant golden rabbit.

Apart from her own ragged breathing, all on the coastal path was silent.

For a second or two, Nell could only look on blankly, shock preventing her imagination from forging too far ahead. Alone on the hill, she surveyed the scene. To the north side, Auntie Suzie’s crumpled Land Rover stood motionless beside the toppled mascot, blocking the passage for an early-morning campervan arriving on the entrance path behind them.

The intact section of the campsite was suddenly populated with adults and children rushing from their tents and caravans, gathering on the grass in clusters to gaze on at the cloud of dust and smoke, which slowly cleared, revealing the children’s playground to be in ruins. Impossibly, the crashed plane appeared to be sitting directly on top of the skate ramp.

Where Albie had just been.

Cold fear rushed at Nell. Where was Albie? Where was Mum? Why hadn’t they come out yet? With rigid fingers, she fumbled to get a grip on her phone and dialled 999. This, Nell would recognise later, would be her flashbulb moment, the memory she would recall for ever more, a vivid technicolour showreel of where-she-was-when-it-happened, in the seconds that separated the before from the after.

‘Ambulance!’ she cried when the operator connected at the other end. ‘There’s been a plane crash at the Golden Rabbit Holiday Park – on the Port Regis-to-Mere road, at the foot of Highcap Hill! I’m there now – I’m on the hill. I can see everything!’ Information spewed from her, startlingly articulate and clear.

‘OK, give me your name, love.’ Patiently the call handler extracted the details she needed while Nell began the breathless race downhill, stumbling on mossy mounds and slippery stone, skidding to a halt as she realised the operator was cutting out, her words drifting through in a disjointed jumble. ‘What – see now?’ the woman wanted to know. ‘Is – hurt? – smoke? ’ell?’

Nell screamed in frustration. ‘I can’t hear you! I can’t hear what you’re saying!’

At last, the line cleared. ‘All right, love. It’s just a poor signal your end. Nell, can you see if the main road is obstructed in any way?’

Nell glanced down towards the road, which was getting busier now with morning commuters. As her coastal path dipped into a shallow valley, she lost sight of the holiday camp altogether, and for several minutes she could tell the woman nothing at all.

‘The road’s clear,’ she replied in a sprinting gasp as she crested the next upward slope.

Uncle Elliot was now out of his vehicle, but slightly stooped over and being assisted by the couple from the campervan stuck behind them.

‘My uncle just got out of the Land Rover – I think he’s hurt. But he’s walking!’ she shouted down the line.

‘Your uncle?’

‘Yes – on the main path. At the campsite – but I still can’t see my—’ A whimper escaped Nell as the words refused to come, and shocked by the sound of it, she bit down on her lip, tasting blood. ‘OK, OK, OK,’ she murmured, forgetting momentarily that the operator was still on the line.

‘All right, Nell,’ the woman said, ‘I’m still here. What’s your uncle’s name?’

‘Elliot Gale. He runs the campsite with my Auntie Suzie.’

‘OK. How close are you to the scene now?’

‘Maybe ten minutes, if I run!’

The line cut out.

Stuffing the phone into her back pocket, Nell used the time to pick up pace on her next sweeping downward descent. She knew her estimate was ambitious; on a good day, at a regular hiking pace, it took at least thirty minutes to descend from Highcap summit to the campsite below. If she put her all into it, maybe she could do it in fifteen?

When she reached the boundary to the birdwatching platform of Kite View, she paused for breath, wincing at the stitch radiating beneath her ribs and the hangover that pooled in her stomach. Below, an untidy line of twenty or thirty campers was now crossing the grassland away from the main site, heading towards the foot of the coastal path. Directing them from the grass clearing at the centre of the tents and caravans, seemingly unscathed, was Auntie Suzie, instantly recognisable in her khaki waistcoat, scruffy pale hair beneath her peak cap.

Nell scanned the line of campers, desperate to spot her mum and Albie among them, but they weren’t there. Sweat ran down the centre of her back and her head pounded, but she swallowed hard, pushing off again at speed just as her phone sprang back to life.

‘Signal’s bad,’ Nell told the operator, panting as she forged on, her boot skidding on the stony slope. ‘We’ll probably cut out again in the next dip.’

‘OK, understood. The emergency vehicles are already—’

But Nell had stopped listening, and she had stopped moving.

Through the smog of the shower block, the small figure of her mother was emerging with yellow gloves dangling from one hand. She looks like a bomb victim, Nell thought, taking in the image in a single appalled gulp. The garish mint green of her cleaning tabard flashed feebly beneath a wash of black dust, and her red hair, usually bundled up in an African scarf, fell over her shoulders in dirty coils.

Unsteadily, Mum paused for a moment, turning this way and that, before throwing down her cleaning gloves and breaking into a run. Tearing off along the footpath, she sprinted, cutting past the farm shop and its fallen awning, heading with purpose in the direction of the children’s playground. For long moments, she disappeared, and Nell watched, breath held.

Across the site, smoke and dust drifted, slowly revealing the true extent of the damage. The aircraft’s tail end lay crumpled flat against the turf of the playground, its nose tilted skyward, its wings snapped clear, one of them now speared through the collapsed roof of the shower block.

‘Nell?’ the operator persisted. ‘Hello, Nell? Are you still there?’

But Nell’s attention was on the children’s playground, just beyond the plane, where something was going on. Mum was back in view.

‘Hang on,’ she barked, impatiently.

To Nell, it looked, bizarrely, as though her mother was shaking a rug, her small frame moving in and out of view, up and down, as she cast aside debris and discharged fresh plumes of dust into the air.

‘My mum’s right by the wreckage,’ she whispered into the phone, as though to raise her voice would risk the worst.

‘Your mum’s there too?’ the operator repeated.

‘Uh-huh,’ Nell replied, flatly. She couldn’t allow herself to feel the relief she ought to about Mum, not until she saw Albie was OK too. ‘It’s . . . it’s the family business. She cleans. She just came out of the shower block. She’s . . . I think she’s looking for my brother.’

Fresh adrenaline surged through Nell’s veins, and she pressed on, closing the gap, bringing the scene into clearer focus. Uncle Elliot was now lying on his side a little way from his vehicle, with a blanket over his shoulders, while the campervan woman sat in a folding chair beside him and spoke into a phone. The campsite had completely vacated, and Auntie Suzie’s campers were all assembled at the base of the coastal path below Nell.

She glanced back towards the horror scene of the playground, just as Mum re-emerged. Stooped low and with the power of someone much larger, she dragged Albie, corpse-like, away from the playground and out onto the deserted grass plain. As Nell watched, immobilised by the terrible sight, one of Albie’s bright tennis trainers detached from his foot. He would be furious at the grass stains he was undoubtedly scuffing up on the heel of that exposed white sports sock, and it was this small detail that almost undid Nell altogether.

Numbly, she watched as her mother gently lowered Albie’s head to the ground and shrugged off her tabard to make a pillow beneath his neck. With urgent movements, she stepped out of her skirt and began tearing strips from it to wind around his arm, tugging hard at the ties before finally dropping to her knees.

Even from here, Nell could see that the yellow of Albie’s favourite sweatshirt was almost entirely stained with blood. With Albie’s blood.

Mum seemed so small as to be childlike, now wearing just her white knickers and tank top as she stooped over her boy, who had matched her in height since his twelfth birthday.

‘Mum!’ Nell called out, waving her arms, her pitch rising. ‘Mum!’

‘Nell?’ Mum jumped to her feet in response, spinning full circle, a frantic catch in her voice, but her eyes never landed on her daughter, reinforcing in Nell that sense of having entirely vanished.

‘I’ve got to go,’ Nell cried into the phone. ‘I can’t—’ She heard the call handler’s protests, but already she was running full pelt, because her little brother was down there, bleeding into the Dorset soil, and she had to tell him she was sorry. To tell him she’d never let him down again.

Breathlessly, she negotiated the craggy downward paths that separated her from Albie, twice tripping on the flapping hems of those damned trousers, grazing her wrists and slicing her elbow on a shard of flint. But the pain barely registered; she was focused only on getting to him, and on batting away the fear that crept coldly at the base of her neck. She was to blame. If she’d just gone home – if she’d never gone out in the first place – none of this would have happened. How could she possibly live with the guilt if her brother didn’t make it? With sudden clarity, she knew that what had happened to her last night was irrelevant, compared with the thought of losing Albie. If she lost Albie, she’d have nothing to live for. Nothing at all.

At the final boundary, Nell leant heavily on the sheep fence, to press her forehead against the cool resistance of the wooden post, steadying herself for the last stretch. When she raised her head, the view below seemed changed. Not so far away now on the coastal path stood the campers, backlit by the bright white of the sun-struck sea, while in the campsite, Mum remained huddled over Albie, and on the entrance path, Auntie Suzie crouched beside Elliot. All, to Nell, seemed disturbingly still – until, directly ahead of her, in the children’s playground, she spotted movement from the smashed aircraft, as the head and shoulders of the pilot rose from the cockpit, his movements cautious as a spaceman fallen to earth.

Aghast, Nell tumbled over the next stile, her gaze never leaving the impossible scene. As she reached the top of the manmade steps that would lead her to the grassland below, the pilot clambered stiffly from the plane and balanced precariously on what little was left of the demolished skate ramp.

Even from this distance, Nell could sense the man’s desolation, in the way his shoulders slumped, his head hung darkly beneath blooded features. He reached down into the smoking hollow of the cockpit and hefted something awkward from the space below. A rucksack? A parachute?—

‘No,’ Nell whispered, feeling her knees buckle as she started down the final stepped decline. ‘No—’

The wailing harmony of emergency vehicles sang through the air as two blue-lit ambulances appeared on the main road up ahead, and, briefly, Nell’s hope soared. But then, before relief even had a chance to take hold, the aircraft in the playground, pilot and all, exploded into flames.

Saturday

The big digital clock on the wall of the hospital family room displayed 18.47; almost exactly twelve hours since the plane landed in the playground of the Golden Rabbit holiday camp. Half a day.

Cathy had been watching the numbers tick slowly upwards since she’d arrived with Albie in the ambulance just after eight that morning, each turn of the hour prompting her to head out into the bleachy blue corridors in search of an update. In search of some hope. Throughout the day, the answers had shifted in small increments: ‘He’s being closely monitored … He’s lost a lot of blood … He’s in good hands … The injuries he’s sustained are concerning … He’s scheduled for surgery … He’s going into theatre at seven.’

When the time arrived, a nurse led her through glaring strip-lit hallways to the pre-op suite, and Cathy kissed his forehead and told him she loved him, all the while knowing that he couldn’t hear her. That he couldn’t speak to tell her, Don’t worry, Mum,

I’m gonna be fine. Now, the clock turned 19.00 and Cathy fired off a text to her sister-in-law.

Albie has gone into surgery. They need to see how bad the damage is before they can say more. What news on Ells?

Suzie returned a typically formal reply. We are still in A&E. Elliot is concussed and they haven’t yet stitched up the gash in his head. They say we’re next. I hope so. Suzie

She always signed off with her name, Cathy noticed, as though it were an email, not a text. They didn’t actually text each other all that often, she supposed. Sometimes it felt to Cathy as though the fifteen-year gap between them was more like a whole generation. She often wondered how her brother and Suzie had stayed together all these decades; Elliot was the same age as his wife but way less uptight. Like chalk and cheese, Dad always said. More like paper and scissors, Cathy would reply with a smirk, and Dad would ignore her, because the quip was well-worn and he didn’t understand why his daughter couldn’t make more of an effort to bury the hatchet.

Does Dad know yet? Cathy texted back, thinking of Nell back home, taking her grandad his dinner next door, under strict instructions not to let on about the crash until they had more news on Albie’s condition.

We haven’t told him, Suzie answered. But I completely disagree with you and Elliot about keeping it from him. The campsite is still his business. The crash was all over the local news at six – national too. Dad won’t be happy if he finds out from someone else. Suzie

Oh, fuck off. He’s my dad, not yours, Cathy wanted to reply. The air crash had taken out landlines in the immediate area, so there was no risk of anyone calling him, and Dad didn’t even own a TV, as her sister-in-law well knew. Suzie was such a know-it-all, and Cathy had been listening to this kind of I’m-older-than-you lecture from her since she was a child, for God’s sake.

Of course, gallingly, on this matter, Suzie was absolutely right. Dad’s fury at being kept out of the loop might well put his heart under more stress than the shock of the news itself, and Cathy really didn’t want another critically ill family member on her hands right now.

I’ll phone Nell, she replied. Get her to drive him in.

She allowed her eyes to return to the clock. Albie had been in surgery for eighteen minutes now. How long did these things take? These investigations. ‘We’ll know when we know,’ one particularly unhelpful auxiliary had told her as they’d wheeled Albie’s bed away less than half an hour ago. What kind of answer was that?

Cathy stared at the phone in her hand and wondered what she should say to her daughter. Earlier, when Nell had arrived with a fresh set of clothes for her, they’d sat silently like two strangers at a bus stop for almost an hour, before Cathy couldn’t take it any longer and sent her home to check in on her grandad. She knew Nell was feeling guilty, and she knew all the girl wanted was for her mother to say it wasn’t her fault, that these things were out of our control, that Albie was going to be fine. But, in the gaping horror of the aftershock, Cathy just couldn’t. She couldn’t tell Nell that she shouldn’t feel guilty, because, God forgive her, she should.

She tapped out a message to her daughter. When Grandad’s had his dinner, bring him to the hospital please.

Why? How’s Albie? came Nell’s swift reply.

He’s in surgery.

Is he OK?

I don’t know, Nell. They’ll tell us when they bring him out. Can you bring my toothbrush and some toothpaste? I’. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...