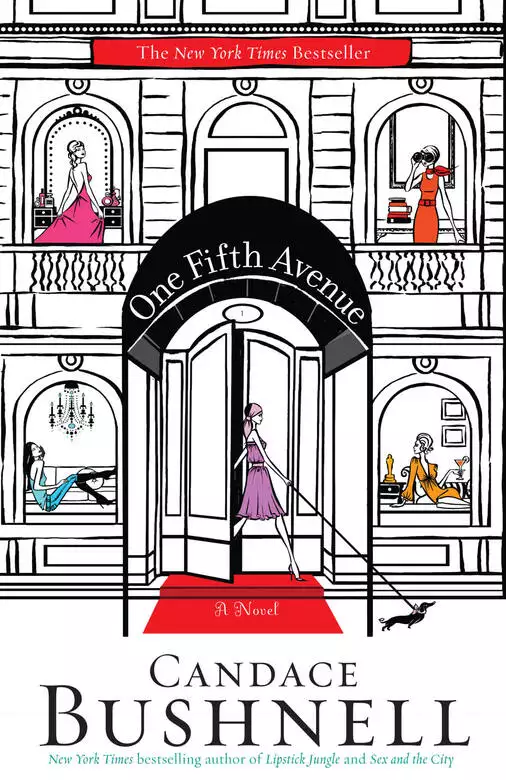

One Fifth Avenue

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

One Fifth Avenue is THE building - the choicest, the hottest, with all the best people. Within its luxuriously thick walls the lives of New York City's elite play out. There is Schiffer Diamond, an over-forty actress who had given up making movies and moved to Europe, until the call to come home gave her the chance to prove that women of style are truly ageless. There is spoiled, self-assured Lola, whose mother is determined to launch her darling daughter into society and the arms of the right man by clawing her way into the building. There is Annalisa, a reluctant socialite who has renounced her law career to be the perfect wife to her workaholic husband, and Winnie, who is married to an underpublished writer and has been the family breadwinner too long for her own - and her marriage's - good. And there is Nini, a glamorous grande dame who has lived at One Fifth Avenue for decades and seen everything from her penthouse view. No one else can capture New York with the brilliant wit and flair of Candace Bushnell.

Release date: September 9, 2008

Publisher: Hachette Books

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

One Fifth Avenue

Candace Bushnell

Houghton, who had raised Wheaten terriers on her estate on the Hudson. Wheaty had required two outings a day to the dog run in Washington Square Park, and Billy, who lived on Fifth Avenue just north of One Fifth, had developed the habit then of walking past One Fifth as part of his daily constitutional. One Fifth was one of his personal landmarks, a magnificent building constructed of a pale gray stone in the classic lines of the art deco era, and Billy, who had one foot in the new millennium and one foot in the café society of lore, had always admired it. “It shouldn’t matter where you live as long as where you live is decent,” he said to himself, but still, he aspired to live in One Fifth. He had aspired to live there for thirty-five years and had yet to make it.

For a short time, Billy had decided that aspiration was dead, or at least out of favor. This was just after 9/11, when the cynicism and shallowness that had beaten through the lifeblood of the city was interpreted as unnecessary cruelty, and it was all at once tacky to wish for anything other than world peace, and tacky not to appreciate what one had. But six years had passed, and like a racehorse, New York couldn’t be kept out of the gate, nor change its nature. While most of New York was in mourning, a secret society of bankers had brewed and stirred a giant cauldron of money, adding a dash of youth and computer technology, and voilà, a whole new class of the obscenely super-rich was born. This was perhaps bad for America, but it was good for Billy. Although a self-declared anachronism, lacking the appurtenances of what might be called a regular job, Billy acted as a sort of concierge to the very rich and successful, making introductions to decorators, art dealers, club impresarios, and members of the boards of both cultural establishments and apartment buildings. In addition to a nearly encyclopedic knowledge of art and antiquities, Billy was well versed in the finer points of jets and yachts, knew who owned what, where to go on vacation, and which restaurants to frequent.

Billy had very little money of his own, however. Possessing the fine nature of an aristocrat, Billy was a snob, especially when it came to money. He was happy to live among the rich and successful, to be witty at dinner and house parties, to advise what to say and how best to spend money, but he drew the line at soiling his own hands in the pursuit of filthy lucre.

And so, while he longed to live at One Fifth Avenue, he could never raise the desire in himself to make that pact with the devil to sell his soul for money. He was content in his rent-stabilized apartment for which he paid eleven hundred dollars a month. He often reminded himself that one didn’t actually need money when one had very rich friends.

Upon returning from the park, Billy usually felt soothed by the morning air. But on this particular morning in July, Billy was despondent. While in the park he had sat down on a bench with The New York Times and discovered that his beloved Mrs. Houghton had passed away the night before. During the thunderstorm three days ago, Mrs. Houghton had been left out in the rain for no more than ten minutes, but it was still too late. A vicious pneumonia had set in, bringing her long life to a swift and speedy end and taking much of New York by surprise. Billy’s only consolation was that her obituary had appeared on the front page of the Times, which meant there were still one or two editors who remembered the traditions of a more refined age, when art mattered more than money, when one’s contribution to society was more important than showing off the toys of one’s wealth.

Thinking about Mrs. Houghton, Billy found himself lingering in front of One Fifth, staring up at the imposing facade. For years, One Fifth had been an unofficial club for successful artists of all kinds—the painters and writers and composers and conductors and actors and directors who possessed the creative energy that kept the city alive. Although not an artist herself, Mrs. Houghton, who had lived in the building since 1947, had been the arts’ biggest patron, founding organizations and donating millions to art institutions both large and small. There were those who’d called her a saint.

In the past hour, the paparazzi apparently had decided a photograph of the building in which Mrs. Houghton had lived might be worth money, and had gathered in front of the entrance. As Billy took in the small group of photographers, badly dressed in misshapen T-shirts and jeans, his sensibilities were offended. All the best people are dead, he thought mournfully.

And then, since he was a New Yorker, his thoughts inevitably turned to real estate. What would happen to Mrs. Houghton’s apartment? he wondered. Her children were in their seventies. Her grandchildren, he supposed, would sell it and take the cash, having denuded most of the Houghton fortune over the years, a fortune, like so many old New York fortunes, that turned out to be not quite as impressive as it had been in the seventies and eighties. In the seventies, a million dollars could buy you just about anything you wanted. Now it barely paid for a birthday party.

How New York had changed, Billy thought.

“Money follows art, Billy,” Mrs. Houghton always said. “Money wants what it can’t buy. Class and talent. And remember that while there’s a talent for making money, it takes real talent to know how to spend it. And that’s what you do so well, Billy.”

And now who would spend the money to buy the Houghton place? It hadn’t been redecorated in at least twenty years, trapped in the chintz of the eighties. But the bones of the apartment were magnificent—and it was one of the grandest apartments in Manhattan, a proper triplex built for the original owner of One Fifth, which had once been a hotel. The apartment had twelve-foot ceilings and a ballroom with a marble fireplace, and wraparound terraces on all three floors.

Billy hoped it wouldn’t be someone like the Brewers, although it probably would be. Despite the chintz, the apartment was worth at least twenty million dollars, and who could afford it except for one of the new hedge-funders? And considering some of those types, the Brewers weren’t bad. At least the wife, Connie, was a former ballet dancer and friend. The Brewers lived uptown and owned a hideous new house in the Hamptons where Billy was going for the weekend. He would tell Connie about the apartment and how he could smooth their entry with the head of the board, the extremely unpleasant Mindy Gooch. Billy had known Mindy “forever”—meaning from the mid-eighties, when he’d met her at a party. She was Mindy Welch back then, fresh off the boat from Smith College. Full of brio, she was convinced she was about to become the next big thing in publishing. In the early nineties, she got herself engaged to James Gooch, who had just won a journalism award. Once again Mindy had had all kinds of grand schemes, picturing she and James as the city’s next power couple. But none of it had worked out as planned, and now Mindy and James were a middle-aged, middle-class couple with creative pretensions who couldn’t afford to buy their own apartment today. Billy often wondered how they’d been able to buy in One Fifth in the first place. The unexpected and tragic early death of a parent, he guessed.

He stood a moment longer, wondering what the photographers were waiting for. Mrs. Houghton was dead and had passed away in the hospital. No one related to her was likely to come walking out; there wouldn’t even be the thrill of the body being taken away, zipped up in a body bag, as one sometimes saw in these buildings filled with old people. At that instant, however, none other than Mindy Gooch strolled out of the building. She was wearing jeans and those fuzzy slippers that people pretended were shoes and were in three years ago. She was shielding the face of a young teenaged boy as if afraid for his safety. The photographers ignored them.

“What is all this?” she asked, spotting Billy and approaching him for a chat.

“I imagine it’s for Mrs. Houghton.”

“Is she finally dead?” Mindy said.

“If you want to look at it that way,” Billy said.

“How else can one look at it?” Mindy said.

“It’s that word ‘finally,’” Billy said. “It’s not nice.”

“Mom,” the boy said.

“This is my son, Sam,” Mindy said.

“Hello, Sam,” Billy said, shaking the boy’s hand. He was surprisingly attractive, with a mop of blond hair and dark eyes. “I didn’t know you had a child,” Billy remarked.

“He’s thirteen,” Mindy said. “We’ve had him quite a long time.”

Sam pulled away from her.

“Will you kiss me goodbye, please?” Mindy said to her son.

“I’m going to see you in, like, forty-eight hours,” Sam protested.

“Something could happen. I could get hit by a bus. And then your last memory will be of how you wouldn’t kiss your mother goodbye before you went away for the weekend.”

“Mom, please,” Sam said. But he relented. He kissed her on the cheek.

Mindy gazed at him as he ran across the street. “He’s that age,” she said to Billy. “He doesn’t want his mommy anymore. It’s terrible.”

Billy nodded cautiously. Mindy was one of those aggressive New York types, as tightly wound as two twisted pieces of rope. You never knew when the rope might unwind and hit you. That rope, Billy often thought, might even turn into a tornado. “I know exactly what you mean.” He sighed.

“Do you?” she said, her eyes beaming in on him. There was a glassy look to les yeux, thought Billy. Perhaps she was on drugs. But in the next second, she calmed down and repeated, “So Mrs. Houghton’s finally dead.”

“Yes,” Billy said, slightly relieved. “Don’t you read the papers?”

“Something came up this morning.” Mindy’s eyes narrowed. “Should be interesting to see who tries to buy the apartment.”

“A rich hedge-funder, I would imagine.”

“I hate them, don’t you?” Mindy said. And without saying goodbye, she turned on her heel and walked abruptly away.

Billy shook his head and went home.

Mindy went to the deli around the corner. When she returned, the photographers were still on the sidewalk in front of One Fifth. Mindy was suddenly enraged by their presence.

“Roberto,” Mindy said, getting in the doorman’s face. “I want you to call the police. We need to get rid of those photographers.”

“Okay, Missus Mindy,” Roberto said.

“I mean it, Roberto. Have you noticed that there are more and more of these paparazzi types on the street lately?”

“It’s because of all the celebrities,” Roberto said. “I can’t do anything about them.”

“Someone should do something,” Mindy said. “I’m going to talk to the mayor about it. Next time I see him. If he can drum out smokers and trans fat, he can certainly do something about these hoodlum photographers.”

“He’ll be sure to listen to you,” Roberto said.

“You know, James and I do know him,” Mindy said. “The mayor. We’ve known him for years. From before he was the mayor.”

“I’ll try to shoo them away,” Roberto said. “But it’s a free country.”

“Not anymore,” Mindy said. She walked past the elevator and opened the door to her ground-floor apartment.

The Gooches’ apartment was one of the oddest in the building, consisting of a string of rooms that had once been servants’ quarters and storage rooms. The apartment was an unwieldy shape of boxlike spaces, dead-end rooms, and dark patches, reflecting the inner psychosis of James and Mindy Gooch and shaping the psychology of their little family. Which could be summed up in one word: dysfunctional.

In the summer, the low-ceilinged rooms were hot; in the winter, cold. The biggest room in the warren, the one they used as their living room, had a shallow fireplace. Mindy imagined it as a room once occupied by a majordomo, the head of all servants. Perhaps he had lured young female maids into his room and had sex with them. Perhaps he had been gay. And now, eighty years later, here she and James lived in those same quarters. It felt historically wrong. After years and years of pursuing the American dream, of aspirations and university educations and hard, hard work, all you got for your efforts these days were servants’ quarters in Manhattan. And being told you were lucky to have them. While upstairs, one of the grandest apartments in Manhattan was empty, waiting to be filled by some wealthy banker type, probably a young man who cared only about money and nothing about the good of the country or its people, who would live like a little king. In an apartment that morally should have been hers and James’s.

In a tiny room at the edge of the apartment, her husband, James, with his sweet balding head and messy blond comb-over, was pecking away mercilessly at his computer, working on his book, distracted and believing, as always, that he was on the edge of failure. Of all his feelings, this edge-of-failure feeling was the most prominent. It dwarfed all other feelings, crowding them out and pushing them to the edge of his consciousness, where they squatted like old packages in the corner of a room. Perhaps there were good things in those packages, useful things, but James hadn’t the time to unwrap them.

James heard the soft thud of the door in the other part of the apartment as Mindy came in. Or perhaps he only sensed her presence. He’d been around Mindy for so long, he could feel the vibrations she set off in the air. They weren’t particularly soothing vibrations, but they were familiar.

Mindy appeared before him, paused, then sat down in his old leather club chair, purchased at the fire sale in the Plaza when the venerable hotel was sold for condos for even more rich people. “James,” she said.

“Yes,” James said, barely looking up from his computer.

“Mrs. Houghton’s dead.”

James stared at her blankly.

“Did you know that?” Mindy asked.

“It was all over the Internet this morning.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

“I thought you knew.”

“I’m the head of the board, and you didn’t tell me,” Mindy said. “I just ran into Billy Litchfield. He told me. It was embarrassing.”

“Don’t you have better things to worry about?” James asked.

“Yes, I do. And now I’ve got to worry about that apartment. And who’s going to move into it. And what kind of people they’re going to be. Why don’t we live in that apartment?”

“Because it’s worth about twenty million dollars, and we don’t happen to have twenty million dollars lying around?” James said.

“And whose fault is that?” Mindy said.

“Mindy, please,” James said. He scratched his head. “We’ve discussed this a million times. There is nothing wrong with our apartment.”

On the thirteenth floor, the floor below the three grand floors that had been Mrs. Houghton’s apartment, Enid Merle stood on her terrace, thinking about Louise. The top of the building was tiered like a wedding cake, so the upper terraces were visible to those below. How shocking that only three days ago, she’d been standing in this very spot, conversing with Louise, her face shaded in that ubiquitous straw hat. Louise had never allowed the sun to touch her skin, and she’d rarely moved her face, believing that facial expressions caused wrinkles. She’d had at least two face-lifts, but nevertheless, even on the day of the storm, Enid remembered noting that Louise’s skin had been astoundingly smooth. Enid was a different story. Even as a little girl, she’d hated all that female fussiness and overbearing attention to one’s appearance. Nevertheless, due to the fact that she was a public persona, Enid had eventually succumbed to a face-lift by the famous Dr. Baker, whose society patients were known as “Baker’s Girls.” At eighty-two, Enid had the face of a sixty-five-year-old, although the rest of her was not only creased but as pleasantly speckled as a chicken.

For those who knew the history of the building and its occupants, Enid Merle was not only its second oldest resident—after Mrs. Houghton—but in the sixties and seventies, one of its most notorious. Enid, who had never married and had a degree in psychology from Columbia University (making her one of the college’s first women to earn one), had taken a job as a secretary at the New York Star in 1948, and given her fascination with the antics of humanity, and possessing a sympathetic ear, had worked her way into the gossip department, eventually securing her own column. Having spent the early part of her life on a cotton farm in Texas, Enid always felt slightly the outsider and approached her work with the good Southern values of kindness and sympathy. Enid was known as the “nice” gossip columnist, and it had served her well: When actors and politicians were ready to tell their side of a story, they called Enid. In the early eighties, the column had been syndicated, and Enid had become a wealthy woman. She’d been trying to retire for ten years, but her name, argued her employers, was too valuable, and so Enid worked with a staff that gathered information and wrote the column, although under special circumstances, Enid would write the column herself. Louise Houghton’s death was one such circumstance.

Thinking about the column she would have to write about Mrs. Houghton, Enid felt a sharp pang of loss. Louise had had a full and glamorous life—a life to be envied and admired—and had died without enemies, save perhaps for Flossie Davis, who was Enid’s stepmother. Flossie lived across the street, having abandoned One Fifth in the early sixties for the conveniences of a new high-rise. But Flossie was crazy and always had been, and Enid reminded herself that this pang of loss was a feeling she’d carried all her life—a longing for something that always seemed to be just out of reach. It was, Enid thought, simply the human condition. There were inherent questions in the very nature of being alive that couldn’t be answered but only endured.

Usually, Enid did not find these thoughts depressing but, rather, exhilarating. In her experience, she’d found that most people did not manage to grow up. Their bodies got older, but this did not necessarily mean the mind matured in the proper way. Enid did not find this truth particularly bothersome, either. Her days of being upset about the unfairness of life and the inherent unreliability of human beings to do the right thing were over. Having reached old age, she considered herself endlessly lucky. If you had a little bit of money and most of your health, if you lived in a place with lots of other people and interesting things going on all the time, it was very pleasant to be old. No one expected anything of you but to live. Indeed, they applauded you merely for getting out of bed in the morning.

Spotting the paparazzi below, Enid realized she ought to tell Philip about Mrs. Houghton’s passing. Philip was not an early riser, but Enid considered the news important enough to wake him. She knocked on his door and waited for a minute, until she heard Philip’s sleepy, annoyed voice call out, “Who is it?”

“It’s me,” Enid said.

Philip opened the door. He was wearing a pair of light blue boxer shorts. “Can I come in?” Enid asked. “Or do you have a young lady here?”

“Good morning to you, too, Nini,” Philip said, holding the door so she could enter. “Nini” was Philip’s pet name for Enid, having come up with it when he was one and was first learning to talk. Philip had been and was still, at forty-five, a precocious child, but this wasn’t perhaps his fault, Enid thought. “And you know they’re not young ladies anymore,” he added. “There’s nothing ladylike about them.”

“But they’re still young. Too young,” Enid said. She followed Philip into the kitchen. “Louise Houghton died last night. I thought you might want to know.”

“Poor Louise,” Philip said. “The ancient mariner returns to the sea. Coffee?”

“Please,” Enid said. “I wonder what will happen to her apartment. Maybe they’ll split it up. You could buy the fourteenth floor. You’ve got plenty of money.”

“Sure,” Philip said.

“If you bought the fourteenth floor, you could get married. And have room for children,” Enid said.

“I love you, Nini,” Philip said. “But not that much.”

Enid smiled. She found Philip’s sense of humor charming. And Philip was so good-looking—endearingly handsome in that boyish way that women find endlessly pleasing—that she could never be angry with him. He wore his dark hair one length, clipped below the ears so it curled over his collar like a spaniel’s, and when Enid looked at him, she still saw the sweet five-year-old boy who used to come to her apartment after kindergarten, dressed in his blue school uniform and cap. He was such a good boy, even then. “Mama’s sleeping, and I don’t want to wake her. She’s tired again. You don’t mind if I sit with you, do you, Nini?” he would ask. And she didn’t mind. She never minded anything about Philip.

“Roberto told me that one of Louise’s relatives tried to get into the apartment last night,” Enid said, “but he wouldn’t let them in.”

“It’s going to get ugly,” Philip said. “All those antiques.”

“Sotheby’s will sell them,” Enid said, “and that will be the end of it. The end of an era.”

Philip handed her a mug of coffee.

“There are always deaths in this building,” he said.

“Mrs. Houghton was old,” Enid said and, quickly changing the subject, asked, “What are you going to do today?”

“I’m still interviewing researchers,” Philip said.

A diversion, Enid thought, but decided not to delve into it. She could tell by Philip’s attitude that his writing wasn’t going well again. He was joyous when it was and miserable when it wasn’t.

Enid went back to her apartment and attempted to work on her column about Mrs. Houghton, but found that Philip had distracted her more than usual. Philip was a complicated character. Technically, he wasn’t her nephew but a sort of second cousin—his grandmother Flossie Davis was Enid’s stepmother. Enid’s own mother had died when she was a girl, and her father had met Flossie backstage at Radio City Music Hall during a business trip to New York. Flossie was a Rockette and, after a quick marriage, had tried to live with Enid and her father in Texas. She’d lasted six months, at which point Enid’s father had moved the family to New York. When Enid was twenty, Flossie had had a daughter, Anna, who was Philip’s mother. Like Flossie, Anna was very beautiful, but plagued by demons. When Philip was nineteen, she’d killed herself. It was a violent, messy death. She’d thrown herself off the top of One Fifth.

It was the kind of thing that people always assume they will never forget, but that wasn’t true, Enid thought. Over time, the healthy mind had a way of erasing the most unpleasant details. So Enid didn’t remember the exact circumstances of what had happened on the day Anna had died; nor did she recall exactly what had happened to Philip after his mother’s death. She recalled the outlines—the drug addiction, the arrest, the fact that Philip had spent two weeks in jail, and the consequent months in rehab—but she was fuzzy on the specifics. Philip had taken his experiences and turned them into the novel Summer Morning, for which he’d won the Pulitzer Prize. But instead of pursuing an artistic career, Philip had become commercial, caught up in Hollywood glamour and money.

In the apartment next door, Philip was also sitting in front of his computer, determined to finish a scene in his new screenplay, Bridesmaids Revisited. He wrote two lines of dialogue and then, in frustration, shut down his computer. He got into the shower, wondering once more if he was losing his touch.

Ten years ago, when he was thirty-five, he’d had everything a man could want in his career: a Pulitzer Prize, an Oscar for screenwriting, money, and an unassailable reputation. And then the small fissures began to appear: movies that didn’t make as much as they should have at the box office. Arguments with young executives. Being replaced on two projects. At the time, Philip told himself it was irrelevant: It was the business, after all. But the steady stream of money he’d enjoyed as a young man had lately been reduced to a trickle. He didn’t have the heart to tell Nini, who would be disappointed and alarmed. Shampooing his hair, he again rationalized his situation, telling himself there was no need for worry—with the right project and a little bit of luck, he’d be on top of the world again.

A few minutes later, Philip stepped into the elevator and tousled his damp hair. Still thinking about his life, he was startled when the elevator doors opened on the ninth floor, and a familiar, musical voice chimed out, “Philip.” A second later, Schiffer Diamond got on. “Schoolboy,” she said, as if no time had passed at all, “I can’t believe you still live in this lousy building.”

Philip laughed. “Enid told me you were coming back.” He smirked, immediately falling into their old familiar banter. “And here you are.”

“Told you?” Schiffer said. “She wrote a whole column about it. The return of Schiffer Diamond. Made me sound like a middle-aged gunslinger.”

“You could never be middle-aged,” Philip said.

“Could be and am,” Schiffer replied. She paused and looked him up and down. “You still married?”

“Not for seven years,” Philip said, almost proudly.

“Isn’t that some kind of record for you?” Schiffer asked. “I thought you never went more than four years without getting hitched.”

“I’ve learned a lot since my two divorces,” Philip said, “i.e.: Do not get married again. What about you? Where’s your second husband?”

“Oh, I divorced him as well. Or he divorced me. I can’t remember.” She smiled at him in that particular way she had, making him feel like he was the only person in the world. For a moment, Philip was taken in, and then he reminded himself that he’d seen her use that smile on too many others.

The elevator doors opened, and Philip looked over her shoulder at the pack of paparazzi in front of the building. “Are those for you?” he asked, almost accusingly.

“No, silly. They’re for Mrs. Houghton. I’m not that famous,” she said. Hurrying across the lobby, she ran through the flashing cameras and jumped into the back of a white van.

Oh, yes, you are, Philip thought. You’re still that famous and more. Dodging the photographers, he headed across Fifth Avenue and down Tenth Street to the little library on Sixth Avenue where he sometimes worked. He suddenly felt irritated. Why had she come back? She would torture him again and then leave. There was no telling what that woman might do. Twenty years ago, she’d surprised him and bought an apartment in One Fifth and tried to position it as proof that she would always be with him. She was an actress, and she was nuts. They were all nuts, and after that last time, when she’d run off and married that goddamned count, he’d sworn off actresses for good.

He entered the cool of the library, taking a seat in a battered armchair. He picked up the draft of Bridesmaids Revisited, and after reading through a few pages, put it down in disgust. How had he, Philip Oakland, Pulitzer Prize–winning author, ended up writing this crap? He could imagine Schiffer Diamond’s reaction: “Why don’t you do your own work, Oakland? At least find something you care about personally.” And his own defense: “It’s called show ‘business.’ Not show ‘art.’”

“Bullshit,” she’d say. “You’re scared.”

Well, she always prided herself on not being afraid of anything. And that was her own bullshit defense: insisting she wasn’t vulnerable. It was dishonest, he thought. But when it came to her feelings for him, she’d always thought he was a little bit better than even he thought he was.

He picked up the pages again but found he wasn’t the least bit interested. Bridesmaids Revisited was exactly what it seemed—a story about what had happened in the lives of four women who’d met as bridesmaids at twenty-two. And what the hell did he know about twenty-two-year-old girls? His last girlfriend, Sondra, wasn’t nearly as young as Enid had implied—she was, in fact, thirty-three—and was an up-and-coming executive at an independent movie company. But after nine months, she’d become fed up with him, assessing—correctly—that he was not ready to get married and have children anytime soon. A fact that was, at his age, “pathetic,” according to Sondra and her friends. This reminded Philip that he hadn’t had sex since their breakup two months ago. Not that the sex had been so great anyway. Sondra had performed all the standard moves, but the sex had not been inspiring, and he’d found himself going through the motions with a kind of weariness that had made him wonder if sex would ever be good again. This thought led him to memories of sex with Schiffer Diamond. Now, that, he thought, staring blankly at the pages of his screenplay, had been good sex.

At the tip of Manhattan, the white van containing Schiffer Diamond was crossing the Williamsburg Bridge to the Steiner Studios in Brooklyn. Schiffer was also attempting to st

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...