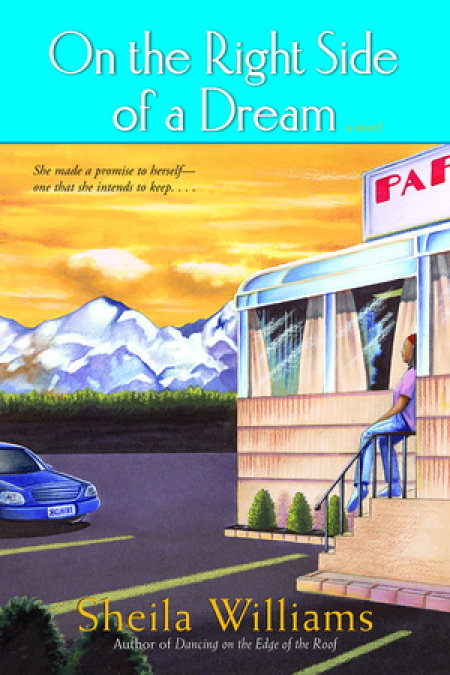

On the Right Side of a Dream

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

After garnering numerous awards for her light-hearted fiction, Sheila Williams pens an “entertaining sequel” (Booklist) to Dancing on the Edge of the Roof (F0160). Having escaped her urban existence, middle-aged Juanita Lewis enjoys her new life in Paper Moon, Montana—but she still has a long list of places she wants to visit. With her true love’s blessing, she embarks on a journey of American exploration. When her eccentric friend Millie suddenly dies, however, she rushes home and learns she has inherited Millie’s bed-and-breakfast. At last Juanita has it all—true love and financial independence! But does this diner cook turned entrepreneur have too much on her plate? This novel overflows with gentle, self-effacing humor.

Release date: April 12, 2005

Publisher: One World

Print pages: 240

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

On the Right Side of a Dream

Sheila Williams

A wise woman said that there are years that ask questions and there are years that answer. For a long time, I was a sorry soul caught between the two—never going forward and afraid to look back. Wedged in between a rock and a boulder and going nowhere. That’s a waste of a life and you don’t get it back. But, I’m a slow learner so none of this wisdom penetrated my hard head until I was past forty. By then, the years of questions had added up. And I didn’t have any answers. All I had was a beat-up suitcase, a tired-looking shoulder bag, and a few pennies. And the courage it took to listen to my own heart when it told me to take the first step, even though I was scared to death.

I ran away from home. Did not stroll, skip, or saunter. I ran as fast as I could. In my journal, I wrote that I was running away from my old life. But I was really running away from no life.

Now, my family was not having any of this running away stuff. You see, they’d been so used to me being a part of their dramas that it never occurred to them that I might want a drama of my own. And not the bad kind, either.

“What’s wrong with you, Juanita?” my sister asked me. “Have you lost your mind?”

My son, Randy, asked me, “Are you ever coming back?”

My kids acted as if I was leaving them to starve to death even though they were grown and living life their way on my dollar and my emotions. I had to fight them to get out the front door. The second-shift supervisor at the hospital where I worked could hardly keep her no-lips from curling up into a Snidely Whiplash smirk.

“Don’t think you can get this position back when you run out of money,” she’d told me. “In this economy, I can fill your job with the snap of a finger.” When she said that, it was my turn to smirk. Exactly when did a nurse’s aide job become a “position”?

The man in the bus station looked at me funny when I told him I was going to Montana to see what was there. He probably thought that I was an early release from a mental hospital. But the little man at the pawn shop hit the nail on the head.

“New life?” he’d asked, handing me the receipt for the suitcases I had just bought. “Where’s that?”

I left to find out.

Some months later, I left Paper Moon, Montana. It was a rainy fall morning and I sat in the cab of Peaches Bradshaw’s truck, crying my eyes out because I was leaving a man who loved me and folks who thought I walked on water and didn’t cook too bad, either. But I wasn’t running away this time. Oh, I still carried a suitcase, a tote bag, and a purse without much money in it. But for this trip, I had something else along that I hadn’t had before. I had a life. And I wore it proudly like a woman wears a big pink hat to church on Easter Sunday.

“I’ll keep your side of the bed warm,” Jess had told me when we’d said our good-byes in the early morning. Those were the only words I needed to hear. What can you say to a man who’ll do that for you? All I could do was bury myself in his arms. If you are loved, it’s enough by itself.

Millie Tilson, Paper Moon’s resident eccentric, glamour girl, and innkeeper, had given me the benefit of her advice and many years of life. However many that was.

“Ohhh, I wish that I could go with you, but the Doc and I are headed to Vegas in a few weeks and we’re taking tango lessons. Did I tell you that?”

“The Doc” was Millie’s “boy toy,” Dr. Angus Hessenauer, a seventy-something retired internist who’d grown up in Lake County, made good in Boulder, and was now back to renovate and live on the old family homestead. Their relationship (Millie said it was an “affair,” not a relationship. “Relationships are what people have with their bankers nowadays.”) was the talk of the town. No one knew exactly how old Millie was but everyone was in agreement that she was at least ten years older than Doc Hessenauer. Maybe more.

“Yes, you told me that,” I said, watching as she unpacked a UPS box. It was her latest order from Victoria’s Secret, a lacy little number in red and a few other very small pieces that could loosely be called “clothing.” That’s all I’m going to say about that.

“Oh, well,” Millie sighed as she checked over the invoice with the focus of a C.P.A. “Be sure to go places that you’ve never been before. That’s when you have the best adventures.”

I laughed. That would be easy.

“Millie, I haven’t been anywhere before!”

Her dark blue eyes twinkled with mischief and wisdom.

“Then you’re going to have a marvelous time, aren’t you?”

I was. Everything would be new to me, every sight, every smell. But would it be “marvelous” as she said? Or, would “marvelous” have to share a space with “boring” or “sad” or “awful”?

“Sometimes, it all comes together, Juanita,” Millie reminded me. “It’s what you do with it. That’s what matters.”

She was right.

A long time ago, it seems a hundred years ago now, on the bus trip from Ohio, I’d made a list of the places that I wanted to go in my life. A wish list. Looked them up on a map, circled them with a highlighter: Los Angeles, the Yucatán, Jupiter, Tahiti, Cairo, Buenos Aires, Ursa Major, Beijing, and Auckland. I had bright orange lines crisscrossing the atlas. When I showed the list to Peaches, she laughed.

“Juanita, I don’t think the Purple Passion will make it across the Pacific. Flotation is not a strong suit of the Kenworth,” she’d told me, referring to her bright purple truck cab. “Beijing! Tahiti! I can see you now in a hula skirt!”

I could see me, too. It was a comical sight.

“Can’t help you with Jupiter. You’ll need an engine bigger than mine for that.”

“Oh, that’s OK,” I said. Jupiter was just a silly thought that popped into my head. If you’re going to make a wish list, make it good. You never know.

“Would you settle for Los Angeles? Or the Grand Canyon? And I think I might be able to manage Denver, although I don’t usually pull the eastern jaunts. Stacy does those.”

Stacy was Peaches’s partner both professionally and personally: a tall, skinny thing with the vocabulary of a truck driver (which she was) and the heart of a poet. She got weepy over Sonnets from the Portuguese.

Peaches grinned. “ ’Course, in a few months, I’ll be heading to San Diego. How about going south into Mexico? Stacy could fly down and meet us if she doesn’t have a run. I have a taste for some real tequila and a few days on the beach,” Peaches commented with a sigh. I knew that thoughts of limes and frosted margarita glasses danced around inside her head.

“It’s a deal,” I’d agreed.

The plan was to head west through Idaho and Oregon, then south into California on I-5. Peaches had a delivery in Redding, then planned to take a detour so that I could see the ocean.

But it rained a lot that fall. And plans are meant to be changed.

“Any other time, I’d say we were lucky to have rain,” Peaches yelled over the roar of the huge engine, Bonnie Raitt’s deep, bluesy voice, and the swooshing sound of the windshield wipers that reminded me of the eyelashes of a giant giraffe. “It could be snow. Shoot, this is October, it should be snow!” she commented, squinting as she tried to see through the sheets of water that poured over the window. “This rain is not a good thing.”

She was right. It got so bad that she pulled off the road a couple of times because she couldn’t see. The storms rolled in from Idaho as they liked to do but instead of moving on and moving out, they brought relatives with them. The sky went dark in the late morning and stayed that way for the rest of the day so that you couldn’t tell when day turned to night. Got so I expected to see Noah and his boat floating by at any minute.

We got used to seeing orange cones and the flashing lights of emergency cruisers. State troopers stood in the middle of the highway directing traffic around fender benders, mud, and rock slides. It was slow going and hard on Peaches. She looked exhausted. And the three mammoth-sized cups of coffee that she’d had weren’t any help.

“I hope you don’t have any business appointments tomorrow morning,” Peaches said, a weary smile lighting up her face.

I shrugged my shoulders.

“I’ll just have my secretary reschedule,” I told her. “I wish I could help you drive, though. Make this trip easier.” I’d asked her once to teach me to drive the Purple Pas- sion and she let me work through the gears. That was a chore. There’s a lot to it. You can’t get it in a one-hour lesson. Making turns, parking, backing up, just putting on the brakes (at seventy miles per hour) with thousands of pounds behind you took some doing.

She snorted and shook her head. She’d taken off her baseball cap and her long, sun-streaked blonde hair fell down her shoulders.

“Don’t worry ’bout it. Hell, I’ve been driving this route by my lonesome for years. It’s a treat just to have a real person to talk to. Half the time, I’m talking to myself. You know how strange that looks?”

The gears complained as Peaches moved through them. A trail of red brake lights wound down the highway, breaking through the soupy view of the window, flickering like Christmas-tree bulbs. The rain was getting worse. It was beyond raining cats and dogs; this was like raining cows and horses. I couldn’t see a thing and didn’t know how Peaches managed. The truck came to a groaning stop. Through the drippiness, a man ran down the center of the highway between the lines of stopped cars and trucks. He waved at the pickup in front of us then headed toward the Purple Passion, motioning for Peaches to roll down the window. His jacket was soaked and the rain dripped off the bill of what used to be a green John Deere baseball cap.

“What’s going on?” Peaches yelled. “Accident?” Words were used with a lot of economy.

“Mud slide, road’s closed,” he yelled back, his eyes blinking to beat back the raindrops that were blowing in sideways. “They’re going to detour to a county highway running southwest. It winds a bit but y’oughta get to the redwoods before your kid goes to college. Have to sit on it awhile, though. They’re just gettin’ started.” He ran off to the FedEx truck in the next lane.

“I guess that’s it. You will be late for that business meeting, Mrs. Louis,” Peaches said, yawning, as she rolled up the window. She leaned into her seat and closed her eyes for a moment to take a catnap.

Later, when the truck began to move again, I studied the rain, the direction that the wind was blowing, and the huge rock-and-mud concoction that had spilled across the highway. I thought about the change of seasons in Montana, where summers are short and winter seems to last forever, or so they tell me. The land is so wide, so open that, even with the mountain ranges, you can see the weather coming from way off. I remember standing on the back porch of the diner with my hand to my forehead like a sentinel, watching a thunderstorm roll in across the Bitterroot and thinking to myself how beautiful it was. The skies turned from blue to milky gray, then to a silvery slate shade. A giant hand had plated the bowl of the horizon with pewter. I used to keep Jess’s dog, Dracula, inside if it got too hot in August, listened to the weather on the radio just to keep up with the temperature. Sometimes, I planned out what I would cook at the diner where I worked based on the weather. If it rained and got a little cool, I put together a soup; if it was as hot as the Sahara, I whipped up cool salads and fruit. In between, I did whatever made me feel good.

I hadn’t done that before I came out west, hadn’t paid attention to the weather. Never even noticed it. If it rained or if it didn’t, none of that ever mattered before I came to Paper Moon. When I worked at the hospital back in Columbus, I carried around a cheap fold-up umbrella (that I’d fixed with masking tape every time it blew inside out) in my tote bag, along with my lunch every day, whether it was hot or not, whether it snowed, whether it didn’t.

I wasn’t rooted to anything but asphalt and concrete. And buildings don’t reflect the season’s changes. Or a life’s changes, for that matter. No way a paved parking lot tells you spring is around the corner or that it’s going to rain. I am now a woman of the earth, a weather vane.

I sniff the air for rain, listen to the birds, and check the western skies for clouds. I grab a handful of dirt to feel how dry it is. I can fix the time of the sunset just by its color. And when the wind blows, I play a game with myself: Where is it coming from? How does it smell? Dust from Texas, magnolia from Alabama, corn from Indiana, pine from British Columbia.

It’s hard to believe now that I lived my life in such a way that I never noticed the rain. And I didn’t notice the sunshine much either. Barely noticed the seasons at all, as if I was immune to rain or shine. Now, that is pitiful. I shook off the memory of that poor woman, closed my eyes, and listened to the swish-swish of the windshield wipers.

Rain has two effects on me; it either makes me sleepy or makes me want to go to the bathroom. Since there weren’t any rest stops in sight and running into a flash flood to pee didn’t appeal to me, I took a nap. I have learned to sleep sitting up with the roar of the Purple Passion’s engines as background music for my dreams. It is a funny combination. In my dreams, I might be running through a meadow filled with wildflowers. But, instead of the smoky molasses smoothness of Roberta Flack’s voice or the gentle sliding sounds of violins, I hear the drone of a truck’s engine or the scraping sound of the shifting gears to go along with the blue skies, gold, red, and purple flowers, and gentle breezes. Oh, well. You have to make do with what you have.

I have a few ideas in my head about what I want to do next, where I want to go. A few ideas, not just one, so when folks ask me, “What you doing next, Juanita?” I sound like an idiot when I answer, “Oh, I don’t know, a lot of things.” Anything I haven’t done, which is just about everything.

Jess and I liked to talk early in the morning, way before the birds got up. In the cool darkness, we would wrap around each other like two hands clasped in prayer and talk and argue and laugh at bad jokes until one of us would fall asleep again, usually me. And Jess would ask, “What you gonna do for an encore, Juanita? Is there a sequel to this great adventure?”

He does not ask me to give up my dreams, whatever they turn out to be. And he doesn’t make me feel guilty for wanting to wander like a gypsy, either. Just lets me know that I am always in his heart.

“You want to get married, old woman?” he’d asked once, nuzzling my neck with the tip of his nose.

Lord, no. I’d be in the running with Zsa Zsa Gabor or Elizabeth Taylor as the most married woman in America.

“I love you, old man,” I told him, “but I’d rather live in sin if you don’t mind.”

My mother is rolling around in her grave. “Better to marry them and be miserable than live in sin and be happy” would have been her motto. I haven’t figured that one out yet. But I am way too old now for bridal white and orange blossoms and all of the magic tricks and illusions that go with them, not that I ever went that way. No time for that. Just need a warm body next to mine. And an open heart.

Jess had laughed. The sound of his laughter, the warmth of his breath on the back of my neck had made me smile. I felt sleepy.

“Thought that I’d better ask,” he’d told me, his voice softening, his words coming out slower. He yawned. “I knew you’d say no, but you’d raise hell with me if I didn’t at least ask.”

“You got that right,” I had told him, closing my eyes again.

At least, I’ve been asked.

“Just make this your home, Juanita,” he says, softly now. He takes my hand and places it on his heart, a warm place on his bare chest. “Make this your home . . .”

I see Jess’s face off and on in my dreams as I fight bulls in Chihuahua, make crepes in a Toronto bistro, or climb Mount McKinley . . . no, take that dream out, I am afraid of heights! Everywhere I go, no matter how far away it is, I see Jess’s face.

“Make this your home . . .” Juanita’s place.

I open my eyes. The rain has stopped but it’s still drippy outside, the dampness slinking off the leaves of the trees like green gravy that hasn’t thickened right. The eastern sky is a strange shade of yellow and orange, the western sky is the color of slate, a dark, angry gray with clouds of silver and black. Zigzags of lightning flicker in the distance. Peaches is playing Nina Simone now, Sinnerman. The clicks of the music are offbeat from the plops of rain that have started to hit the windshield. Peaches turns on the wipers again. I close my eyes.

Sometime, during my dream, Nina’s voice fades and the background music that comes from the truck’s engine is replaced by a loud, heavy roar. Not a groan or screech like an old car that gets stuck in first gear. And it gets loud, then it gets soft, and then it gets loud again. Over and over and over. But when the roar softens, I hear birds calling to each other and the clanging of a bell in the distance. And splashing. I am running in my bare feet through a meadow of water instead of wildflowers . . . splashing?

I woke up so fast that I jumped and almost hit my head on the visor. The truck has stopped; its engine idling. The cab was quiet and empty. No Peaches. I looked around the parklike setting and then I stared. I rubbed my eyes. I didn’t believe what I saw. Peaches waved her arms to get my attention.

“Hey, Miss America!” she screamed. “I hope you got a thong bikini with you!”

I stared.

She looked like hell with her pants legs rolled above her knees. Peaches has legs like tree trunks. There was a fairly strong wind and her hair was flying every which way. She looked like a kid in a Disney World commercial.

But that’s not what I was staring at.

I didn’t even bother to open the door; I leaned out of the window, just looking at this thing in front of me. It roared and it crashed against the rocks. It’s gray, no. It’s kind of bluish-gray, no, it’s green. I didn’t know what color it was but it was big and loud and it went on forever.

And I have only seen it in movies.

I ran to the water’s edge, kicked off my shoes and socks, rolled up my pants, and stuck my foot in. And shrieked!

The water was cold!

“It is late fall, Juanita,” Peaches yelled. “Even if it is California!”

I have always wanted to see the ocean. I’d heard about it and read about it and I’d seen it on TV but nothing gets you ready for the real thing. It comes in and goes out and comes in again and the white-tipped waves and the foam look the same every time. But they aren’t the same.

I put my hand up to my forehead and looked out to the end of the world, looking farther than I did when I looked east across the Montana plains toward Illinois. And I wondered now if those ancient sailors weren’t right. The world is flat. The pelicans dove after fish and bobbed along the water like the apples we used to grab with our teeth from my grandmother’s tin tub. The gulls screeched. I stood there with my mouth open in amazement.

“And I thought I was country!” Peaches teased me. “You haven’t seen the ocean before?”

Why? Does it show?

“No, I haven’t.” I closed my eyes and took a deep breath and the salty air filled my lungs. The air smelled deep, rich, and old and I would not forget the smell as long as I live.

I wonder how the first woman felt, seeing this water for the first time. Did she stand here, with her mouth open and her eyes closed and smile as the heavy ocean breezes whipped around her face? Or did she just stare, eyes unblinking, wondering how far it went, what moved beneath the water, and if this rock that she stood on was the end of the world?

She was probably a lot more practical than I was. She probably thought about food, fishing, or building a boat.

I was just too awestruck for those kinds of thoughts.

I stood there until my toes went numb from the cold water. Just stood there in one place. I looked down at my feet and watched the water come in over my toes and then go back again. And each time I thought it might be the same water. But, of course, it wasn’t.

As we drove away, it occurred to me that’s what I want—for something, just one thing, to stay the same. But only good things. Could they please stay good, ’cause I’ve had enough ugliness in my life. I have moved away from that mess, and I want someone to tell me that the joy I’ve found will stay with me awhile. That I’ll be able to pull it over my head and wear it like an old soft sweatshirt whenever I need it, for as long as I need it.

You know all those cities I have wanted to visit? Buenos Aires, Beijing, New York, Hong Kong? I have learned something new about myself: I don’t like cities much anymore.

Peaches drove into Los Angeles from the north. Some miles out I saw an orange-brown cloud that floated over the skyscrapers like a shawl thrown over a woman’s shoulders. But this was not a delicate, soft length of cashmere that was made to keep the evening chill away. It was a rough wool blanket, scratchy and thick. In some places, the haze was murky and more brown than orange. And it wasn’t lightly perfumed. It was stinky.

We were traveling through the city on I-5 and, in both directions, the traffic was bumper-to-bumper, moving slower than a constipated snail. Car horns honked, middle fin- gers went up every place you looked, and I saw more fists raised in the air on that highway than I had in 1969 at a Black Panther rally.

“Must be some accident,” I commented. “They’d better get it cleared out soon. This is a mess.”

Peaches chuckled.

“There’s no accident; it’s like this all the time. In LA, everybody drives. Everybody. The freeway looks like this all day. You might get a clear highway at 3:00 am, which is when I usually come through here.”

“Oh,” was all I could think of to say. I was used to cities but not ones this spread out. Even Cleveland was not this big or this busy. I had seen traffic, but not like this. You couldn’t pull over, you couldn’t pull off. You were stuck.

But when we finally got off, somewhere in the central part of the city, I think, I saw things that I was familiar with. It didn’t take me long to realize that I didn’t want to be familiar with them anymore: the hustle and bustle and noise of buses, diesel fuel blowing from their exhausts and music that I didn’t want to hear blasting from cars as they bounced down the avenue. The souped-up Firebirds had speakers bigger than their engines. All you heard—and felt—was the bass thumping. The yelling, the cursing, the boarded-up buildings and piece-a-cars sitting at stoplights. We drove down one street and I thought that I’d passed into the Twilight Zone of lives lived. I saw myself walking down the avenue, carrying a bag of groceries or standing back from the curb, waiting for a bus. It was as if someone had said “Welcome back, Juanita.” Young boys stood around and didn’t seem to be doing anything except trying to look as if they were the alpha and the omega, while they tried to keep their pants from falling down around their ankles. Do they know that they walk funny? And there was always someone looking out for the uniformed men and their flashing lights. I had to blink to keep from seeing Rashawn on those corners, digging a huge roll of Fort Knox–backed paper out of his pocket, explaining his position in a low, soft but menacing tenor. Hundreds of miles away and in cities in between, there were street corners and alleys and vacant lots just like the ones I left behind. That didn’t make me feel good.

There were people everywhere, walking fast and wearing sunglasses. Lots of sun, lots of noise. And not much grass and no pine trees and no lakes or rivers, and we were too far into the city to see the ocean anymore. Later, I remembered seeing the mountains at dusk as they struggled to show me their beauty through the murky haze. I saw the “HOLLYWOOD” sign, too, from a distance. I hadn’t been there but a few hours and I’d already decided that I had seen enough.

But I was wrong.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...