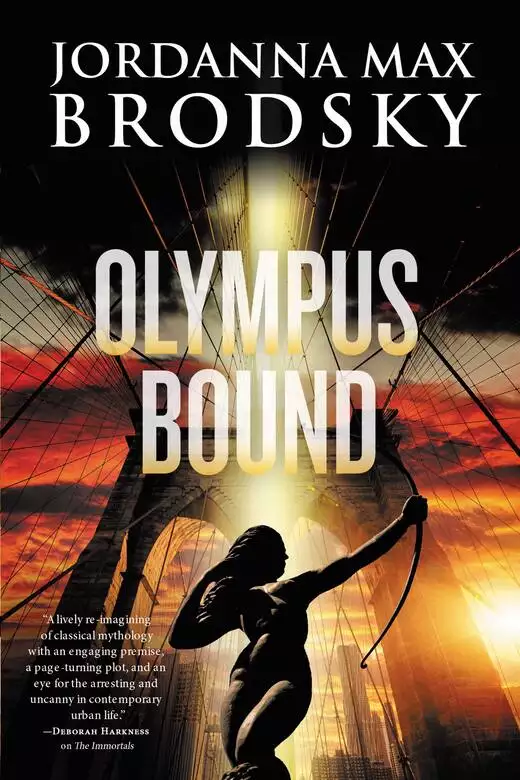

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Manhattan has many secrets. Some are older than the city itself.

Summer in New York: a golden hour on the city streets, but a dark time for Selene. She's lost her home and the man she loves.

A cult hungry for ancient power has kidnapped her father and targeted her friends. To save them, Selene must face the past she's been running from—a past that stretches back millennia, to when the faithful called her Huntress. Moon Goddess. Artemis.

With the pantheon at her side, Selene must journey back to the seat of her immortal power: from the streets of Rome and the temples of Athens—to the heights of Mount Olympus itself.

Release date: February 13, 2018

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 512

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Olympus Bound

Jordanna Max Brodsky

She walked with silent tread on wide basalt paving stones still warm from the unrelenting summer heat. Her stealth was superfluous: Even if her boots scuffed the street, the piercing drone of cicadas would drown out any sound, and the man she hunted seemed oblivious to everything but the mausoleums around him.

Yet she studied him with a hawk’s keen gaze. He was young, clean-shaven, his weak chin and protruding nose accented by blond hair shorn mercilessly close to the scalp. His haircut and muscled physique proclaimed him a soldier. Another foolish mortal recruit in an ancient battle between gods.

The Huntress felt no sympathy. He might be a mere foot soldier, but his army had destroyed her life. They had ripped her from the world she knew, and now they threatened what little family she had left. Somewhere, they held her father captive. Somewhere, they tortured him and prepared him for sacrifice.

Perhaps right here in Ostia.

Either this young man would lead her to her father or he would die. Simple as that.

She followed his gaze to the necropolis’s older buildings, each pockmarked with niches just big enough to hold an urn brimming with ashes. The more recent mausoleums, she saw, housed grand sarcophagi instead. Even the passage of centuries wouldn’t erase the scenes of myth and history so deeply carved into their marble sides.

The young man paused before one of the stone coffins that flanked the mausoleum’s entrance. With a reverent finger, he traced its sculpted depictions of Sun and Moon, Birth and Death.

Then he quickly crossed himself.

The Huntress shuddered: In this pagan city, a mere twenty miles from the Empire’s seat in Rome, the Christian gesture seemed a harbinger of things to come.

Once, she’d watched with pleasure as pious Romans sent their loved ones skyward on the plumes of funeral pyres. The smoke would reach the very summit of Mount Olympus and swirl about the feet of the gods themselves. But more and more, the Romans chose to bury their dead within these marble tombs, where the corpses could await bodily resurrection. A sign, she knew, that soon the Empire’s citizens would abandon the Olympians entirely, praying only for their promised reunion with the Christ.

The Huntress imagined the richly bedecked corpses in their cold tombs. Meat turned to rot turned to dust, she thought with disgust. The Christians waited in vain for a resurrection that would never occur and a god who did not exist. A bitter smirk lifted the corner of her mouth. It serves them right.

At least for now, the Olympian Goddess of War and Wisdom still guarded Ostia’s main gate with her stern gaze: Minerva, whom the Greeks called Athena, carved in stone with upswept wings and a regal helmet. The sight gave the Huntress a measure of comfort. We’re not completely forgotten. Not yet.

She hid in Minerva’s moonshadow and watched her prey leave the necropolis behind as he ventured into the city itself. He strode down the wide avenue of the Decumanus Maximus, past empty taverns and shops, guildhalls and warehouses. The man wore all black as camouflage in the darkened town, but he took few other precautions, walking boldly down the middle of the deserted thoroughfare.

He clearly hadn’t counted on Minerva’s vengeful half sister following in his wake.

He passed the public baths, bedecked with mosaics of Neptune, and the amphitheater, adorned with grotesque marble masks, before finally turning off the avenue to wander deeper into the sleeping city. Only then did the Huntress emerge from behind her marble sibling like a statue come to life—as tall and imperious as Minerva herself, moving with such grace and speed she seemed to float on wings of her own.

She darted silently from shadow to shadow. With her black hair and clothes, the Huntress melted into the night. Only her silver eyes gave her away, reflecting the moonlight like deep forest pools.

As she passed the darkened buildings, she could imagine how they’d appear when full of life. Vendors and merchants would clamor for attention, the perfume of their leeks and lemons fighting the stench of the human urine that produced such brilliant blues and reds in the nearby dye vats. The warehouses would bulge with foreign grain and local salt. Shopkeepers would hawk elephant ivory from the colonies in Africa, fish from the nearby Mare Nostrum, and purple-veined marble from Phrygia in the east, all destined to sate the appetites of the wealthy Romans a day’s journey up the river. Great crowds of toga-clad men and modestly veiled women would bustle down the Decumanus Maximus, pushing their way past ragged children begging for scraps. While some headed for the amphitheater’s worldly pleasures, others processed to the grand temples to offer sacrifices to Vulcan or Venus—or even to the Huntress herself.

But as she followed her prey down an alley bordered by tall brick tenements, she knew this man sought a very different sanctuary. Of the dozens of temples in Ostia, a full fifteen housed a cult dedicated to a single god: a deity not numbered among the Olympians, one who would never claim as many followers as the Christ. Yet one who held the power to destroy her.

Mithras.

Her heart picked up speed. This could be the end of her search. The most famous of Mithras’s sanctuaries lay at the end of the alley: the Mithraeum of the Seven Spheres. Unlike the Olympians’ temples, graceful public edifices with open colonnades and wide entrances, Mithras’s shrines lay tucked into caves or small buildings, where his rites were kept secret from all but the cult’s initiates. Harmless rites honoring a harmless god—or so the Olympians had once thought. Now the Huntress knew better.

Fire scorching my flesh. Water flooding my lungs. Torture of both body and soul. The memories cracked across her brain like a whip. She forced them aside, turning her attention to the temple before her.

From the outside, the mithraeum seemed no more than an unadorned shed of layered brick. Locked iron grates sealed off the single small window and narrow doorway. The Huntress had searched the mithraeum before and found no evidence of her father’s prison. Then again, the cult’s leader—the Pater Patrum—was notoriously wily. The entrance to their lair might be here after all, she hoped, taking a careful step closer to her quarry.

The young man in black fished a pair of lock picks out of his pack. The gate squealed open. He strode forward slowly with a gasp of reverence.

The Huntress repressed a disappointed groan. He didn’t look like a man returning to his cult’s headquarters: He looked like a worshiper entering the Holy of Holies for the first time. This is a pilgrimage. A holy errand. The rest of his army waits elsewhere with their Pater Patrum. And that means my father is elsewhere, too.

She’d hoped to simply follow her prey to his cult’s base, reconnoiter, then devise a plan to rescue her father. Now she’d need to force the correct location out of him instead. Unfortunately, initiates into this cult never broke, even under torture.

At least so far.

She slipped to the side of the barred window and peered inside the cramped shrine. Low platforms bordered a central aisle so the cult’s members could recline during their ceremonial feasts. Black-and-white mosaics covered the platforms and floor, their designs faded and chipped; though her night vision rivaled a wolf’s, she couldn’t decipher the images in the dark. But when the man pulled a small lamp from his bag, she saw the signs of the zodiac adorning the feasting platforms: a fish for Pisces, balanced scales for Libra, two men for Gemini.

Along the length of the aisle, seven black mosaic arcs on the floor symbolized the seven celestial spheres that gave the mithraeum its name. On the platforms’ sides, the tiles formed crude representations of the Olympians—or rather, of the heavenly bodies named for them. A woman holding an arching veil above her head for the planet Venus, a man with a spear and helmet for Mars. The Huntress saw herself there, too: a woman bearing an arrow and a crescent. Fitting symbols for the one called Diana, Goddess of the Moon, by the men who usually worshiped in this sanctuary. Across the Aegean, the Greeks named her Huntress, Mistress of Beasts, Goddess of the Wild, and above all—Artemis.

What name would this man use if he turned around and saw me? she wondered. Pretender? Pagan? Likely, he’d dispense with such niceties and just slice out my heart.

At the far end of the aisle hung an oval relief that encompassed the cult’s entire religion in a single carven image: the “tauroctony”—the bull killing. Mithras, handsome in his pointed Phrygian cap, perched on the bull’s back, one knee bent and his other foot resting on a rear hoof. He plunged his knife into the beast’s neck, completing the sacrifice. A dog, a snake, a scorpion, and a crow encircled the bull. Like everything else in Mithraism, the image contained several layers of meaning. To a woman like the Huntress, who preferred a world of starkly defined categories—night and day, female and male, immortal and mortal—such complexities provided yet another reason to despise the cult.

The animals in the tauroctony symbolized the constellations that rotated across the sky on the celestial spheres. Mithras, or so his followers believed, controlled those spheres. To some who feasted atop the sanctuary’s platforms and offered sacrifices upon its altar, Mithras was only that: a god of stars, one more deity among the dozens worshiped by Ostia’s citizens. But not to the young man gazing upon the tauroctony with a fanatic’s fervor. To him, Mithraism was no mere Roman mystery cult; it was the truest form of the one religion that terrified the usually fearless Huntress: Christianity.

According to the cult’s pseudo-Christian doctrine, the shifting of the celestial spheres would usher in the “Last Age,” a twisted version of the biblical End of Days. Mithras-as-Jesus would walk the earth once more, bestowing salvation and eternal life upon his followers. Only one thing stood in the way of that promised resurrection: the existence of the Olympians. Thus, to make way for their savior’s return, the Mithraists had sworn to destroy the gods.

And now, finally, the Huntress thought, imagining the pain she would inflict on the man before her, the gods are fighting back.

She watched him crouch before one of the black mosaic arcs; he pressed a finger against the tiles, tracing the seam as if he—not his god—could shift the celestial sphere it represented and move the world into the Last Age.

He reached inside his pack for a pouch of tools. A line of sweat trickled down his smooth jaw as he placed the blade of a chisel against the floor and raised a hammer.

The Huntress wasn’t about to let him steal the mosaic. She didn’t care about preserving some other god’s holy artifact, but she didn’t intend to let the thief get what he’d come for. As an authentic sacred symbol, the arc might hold some unknown power. More than one Olympian had died at the hands of a Mithraist wielding a divine weapon—she couldn’t let the cult acquire any additions to their arsenal.

Very slowly, the woman once known as Artemis, the Far Shooter, turned away from the window and slid her pack off her shoulders. Soundlessly, she withdrew two gleaming lengths of metal and screwed them together at the handgrip to construct a divine weapon of her own: a golden bow forged by Hephaestus the Smith.

She slipped two arrows between the knuckles of her right hand and aimed their razor-sharp tips at the back of the thief’s neck. This would be much easier if I could just kill him right now, she thought. But that wasn’t part of the plan. She needed him to talk first. And she couldn’t simply shoot him in the leg and tie him up—she’d tried that with the last Mithraist she’d stalked. He’d been about to haul off an altar from a mithraeum in Rome. When she’d charged toward him, her arrow at the ready, he’d simply used his own dagger to stab himself in the heart before she could elicit more than a terrified moan. Clearly, the Mithraists were under strict instructions to avoid capture at all costs.

She spread her knuckles a little wider. With a nearly inaudible thrum, both arrows flew between the window bars and into the sanctuary. The young man grunted in astonished pain and dropped his tools as the shafts simultaneously pierced the backs of both his hands. He tried to rise, but she tore through the doorway, moving nearly as fast as the arrows, and smashed him to the ground; the back of his skull thwacked against the tiles. The lamp rocked, its beam spotlighting the impassive face of the carven Mithras watching the chaos below.

She grabbed the shafts in the thief’s hands and stood above him, her feet braced on either side of his hips.

“Tell me where the rest of your friends are, mortal.”

He stared up at her, pale eyes narrowed with pain, but said nothing.

The Huntress shook her head with a frown. “Is that how you want to play this? Do you know who I am?”

His lips twisted. “Do you?”

She barked a laugh in his face. “Right now, I’m She Who Leads the Chase. And you’re my prey.” She levered the shafts wider, tearing at the holes in his hands. “Don’t forget—some predators like to play with their food. So start talking while you still have a few fingers left.”

Professor Theodore Schultz usually spent Columbia’s summer session teaching small seminars to an eclectic mix of the university’s overeager and underachieving. On days as nice as this one, when the sunlight burned hot and the breeze blew cool, he liked to bring his classes onto the quad. Surrounded by youthful faces—enthusiastic and bored and everything in between—he imparted his love for myth and history in much the same way he imagined Plato or Aristotle might have in ancient Athens’s outdoor agora.

But today Theo sat on the quad with only books and notes to surround him. He barely noticed the smell of new-cut grass or the laughter of a nearby circle of students playing Frisbee. Despite the sun beating on his shoulders, his mind kept tumbling back to the previous December. He could still feel the wind’s bite, the snow’s sting. It all came back in an instant: the desperate flight over New York Harbor in Hermes’ winged cap, the weight of Selene’s limp body, her sad “I love you, you know” as she pushed away his grip and slipped through the clouds. He’d been spared the sight of his lover’s body slamming into the water and splintering apart. That didn’t stop him from imagining it every time he closed his eyes.

When he’d first met Selene, he’d thought her odd. A private investigator who kept the world at bay with an icy stare and a bitter laugh. Her reticence made sense once he learned—after a week of terror and elation—that she was actually the Greek goddess Artemis. As with all the Olympians, her powers had faded after millennia bereft of worship but, unlike her avaricious kin, Selene had never stooped to brutality to restore her strength.

Nonetheless, she’d been unable to prevent the series of human sacrifices that had restored many of her abilities. With Theo at her side, she’d become an avenging goddess once more, her senses keen as a hawk’s, her strength beyond mortal imagining. He’d thought her invincible. He was wrong.

After her death at the hands of the Mithraic cult, he’d been broken in both body and spirit, unable to eat, barely able to speak. For the first time in his thirty-three years, he’d thought death would be easier than living. With his friends’ help, he’d finally moved out of that darkness, but he’d still spent the spring semester too devastated by grief to do more than sleepwalk through the classes he supposedly taught. The university administration readily agreed he should take the summer off. They probably imagined he’d spend it recuperating on a beach. Instead, he’d barely left the library, and when he did, on a day like today, he took the books with him.

He adjusted his glasses and rolled his neck. You’re a Makarites, he reminded himself. A “Blessed One.” You can find the answers you seek, just like Jason found the Golden Fleece. In antiquity, epic heroes such as Jason and Perseus had won the title of Makarites by feats of arms. Theo, on the other hand, had earned the epithet through his studies of the gods and their stories. His status as a Makarites attracted the Olympians; it even allowed him to use the divine weapons most of the gods were too faded to wield themselves. But so far, it hadn’t helped him on his current—and most vital—quest.

He put aside a treatise on Platonic solids and pulled a narrow wooden sounding board from his satchel. Hunching over it, he plucked the single string.

“Didn’t know you were the hippie sing-along type.”

He looked up to see Ruth Willever standing before him, her face alight with gentle teasing.

“To what do I owe this honor?” He managed an answering smile for his friend.

“I saw you working outside, and I was done at the lab, so I thought I’d pick you up and walk you home.”

“I feel like a fifties schoolgirl. You want to carry my books?”

She laughed too heartily for his lame joke, no doubt thrilled that he’d attempted any humor at all.

“I’ve got plenty of books of my own, thank you.” She lifted her capacious tote bag, probably full of tomes on kidney function or enzyme structure or something else Theo found impressive and soporific in equal measure. He didn’t ask why she was coming over to his house; since he’d lost Selene, Ruth had become his unofficial housemate and perennial dinner guest. If it weren’t for her, he wouldn’t eat at all. “It’s six o’clock,” she reminded him.

“I thought I still had half an hour before my daily force-feeding.”

She plopped down beside him, hiking her skirt to her knees so she could stretch her bare legs across the cushion of grass. “I’m early. Too nice a day to stay at a lab bench.” She glanced at the sounding board on his lap. “Do I even want to know what that is?”

“It’s a monochord.” He plucked the single string again.

“Seems like you’d play some pretty crappy songs with only one string.”

“It’s more than a musical instrument. It’s an ancient experimental apparatus.”

Ruth’s eyes lit. No skepticism, no doubt, just complete fascination. “Explain.”

So he did. He’d spent so long alone with his research that sharing his findings—even the limited portion he could allow Ruth to know—felt like kindling a long-dormant spark. In the grief of the last six months, he’d lost sight of his lifelong passion for learning. Now Ruth’s excitement fed his own, and he found himself actually enjoying his discoveries for the first time since he’d made them.

He lifted the monochord with a hint of his old flair for theatrics. “I’m about to demonstrate the discovery that fundamentally altered mankind’s perception of the universe.”

Ruth put a hand to her heart in a suitably dramatic gasp. “My goodness. Please go on.”

The gesture made him pause. Teasing, play, fun … they still felt awkward to Theo. He felt like a stroke victim deprived of speech, laboriously relearning the words he’d known since childhood. Ruth was his therapist, coaxing and prodding him toward recovery even when she pretended not to. Now she sat staring at him hopefully. Waiting.

“The Greeks once sought the answers to life’s mysteries in myth,” he said finally.

Her smile froze, dimmed. Theo, too, had once sought answers in the ancient stories. In a woman who’d stepped out of myth itself to take over his life. A woman light-years away from everything Ruth represented.

“But eventually,” he went on, ignoring her obvious discomfort, “as their civilization progressed, Plato and Socrates and the other philosophers began to look for new ways to understand the world.”

“They turned to science?” The sudden insistence in Ruth’s tone pulled him up short. It was the closest she’d ever come to outright begging him to finally move past Selene and turn to her instead.

“Yes, they did,” he said with careful emphasis. He looked away from her flash of disappointment and down to his instrument once more. “Not all at once, not very quickly, but yeah. Greek philosophers walked along a bridge between worlds, trying to reconcile their religious beliefs with their new understanding of logic and reason. It all started with Pythagoras.”

Ruth crossed her legs and leaned her chin on a fist in a pose of determined interest. “A squared plus b squared equals c squared,” she said with forced cheer.

I don’t deserve her, Theo thought, not for the first time. Another woman would’ve gotten fed up with my depression months ago. “I see you haven’t forgotten ninth-grade geometry,” he said, offering a small smile. “But the truth is, Pythagoras probably didn’t discover his right-triangle theorem; the Babylonians knew about it long before the Greeks. His real contribution”—Theo lifted the monochord—“was this.”

He plucked the string once more. Then he placed a finger exactly halfway along it and plucked it again, the note considerably higher. “See, I make the string half as long, and the new note is exactly one octave above the first.” He slid his finger down the string. “If I stop the string two-thirds of the way down, it produces a perfect fifth. Make it three-quarters instead, and we get a perfect fourth.” He demonstrated each interval in turn, then repeated the pattern as he kept talking. “Those three ratios—one to two, two to three, three to four—produce three intervals that just happen to be the most pleasing to the ear, at least in Western music.”

Seeing Ruth’s foot tapping, he couldn’t resist altering the rhythm of the notes just slightly and launching into the guitar riff from “Wild Thing.” Ruth’s eyebrows shot upward and soon she was crooning, “You make my heart sing!” in her sweet contralto, twitching her fists in a series of highly restrained dance moves.

Theo couldn’t help grinning and singing along. I haven’t smiled this much in months, he realized. It was almost enough to make him forget the real purpose behind his research into Pythagoras. Almost.

He finished the song with the closest approximation to a trill he could coax from the single string and then gave Ruth a round of applause. She bowed shyly and lay back on the grass with a laugh, her head only a few inches from his lap. She squinted against the sun, then shaded her eyes and tilted her face toward him.

“So what do your harmonic ratios have to do with Mithraism?” she asked carefully.

Ruth had learned the truth about the Athanatoi—Those Who Do Not Die—the night he lost Selene. Sometimes he thought she didn’t totally believe it all—his semi-immortal girlfriend and her Olympian family, the ancient Mithras cult out to kill them led by Saturn, Selene’s own grandfather—but she pretended for his sake. She knew Saturn had escaped after causing Selene’s death, and she believed that Theo’s research aimed at finding him again. A hundred times, she’d told him revenge wouldn’t bring him happiness. He’d managed to convince her that he just needed to stop the Mithraists before they hurt anyone else. She didn’t like his explanation, but she’d finally accepted it.

Too bad it wasn’t true.

“Mithraism is a syncretic religion,” he told her now. “It combines elements from all sorts of sources. And some of their beliefs about astronomy and salvation may have been inspired by Pythagoras.” That much was true, although it was far from the real reason for his interest.

“Huh. And I thought Pythagoras was just a mathematician,” Ruth said a little wistfully, as if nostalgic for a time before the gods had waltzed into her life. Yet she’d stuck by Theo for the last six months, nursing him through the injuries—both physical and otherwise—that he’d received the night he and Selene drove the Mithraists from New York.

“Nope, definitely more than a mathematician.” Theo reclined on his elbows so she wouldn’t have to crane her neck. “His discovery—that mathematical ratios produce real-world harmonies—changed the Greeks’ entire understanding of the world. It was like they’d uncovered a secret language that held the keys to existence. After all, if mathematics and numbers underlay something as fundamental as music—as harmony—then maybe they underlay the rest of the world, too.”

“They do,” she offered. “I mean, that’s what scientists believe.” She blinked at him, her face only a foot from his own. “That math and algorithms and quantifiable evidence can explain everything.”

“So says Dr. Ruth Willever, the microbiologist,” he teased. “A poet might disagree.” A classicist might disagree, he amended silently. Math can’t explain why even as I’m staring at Ruth’s smile, I’m thinking of Selene’s. Only the ancient elegies can do that. A snippet of the Roman poet Meleager floated across his brain.

Where am I drifting?

Swept on by Love’s relentless tide,

Helpless in my steering,

Once more to doom I ride.

“Theo?” Ruth laid a gentle hand on his shoulder and didn’t let go.

“Hmm? Sorry. I was …” With Selene, he was about to say, but Ruth cut him off.

“You were about to tell me what you’re doing with the monochord,” she prompted, heading off his melancholy. “I still don’t see why you’re researching harmonic ratios in the first place.”

Theo pulled away from her touch and plucked the string again thoughtfully. “The Pythagoreans didn’t understand the physics behind the note’s frequency, but they understood that the ratios of the lengths of the string related to the pitch of the sound. And they decided that those same digits that make up the harmonic ratios—one, two, three, four—must be the fundamental numbers in the universe.”

He put the monochord aside and grabbed one of his notebooks, flipping to a page of his more innocuous scribblings. He showed Ruth a sketched figure: four dots in a row, then three above it, then two, then one, creating an equilateral triangle consisting of ten total dots.

“The Pythagoreans called this triangle a tetractys,” he explained. “A ‘fourness’ that represented the perfect number. They thought its unity, its symmetry—four lines, four numbers, three equal sides of four dots each—must be magical.”

Ruth looked skeptical for the first time. “Magical? More like basic geometry.”

“They thought the tetractys might be part of a larger pattern.” He searched for the right way to explain the ancient mysticism to Ruth’s logical brain. He couldn’t tell her too much—she’d probably have him committed if she knew the whole truth—but he always thought better aloud. It was why he’d liked having a partner.

Before thoughts of Selene could derail him again, he pressed forward with his explanation. “Remember how the Mithraists believed in shifting the celestial spheres to bring about the Last Age, so they could achieve salvation with their resurrected god?” Ruth nodded. “Well, the Pythagoreans believed something similar: that the ultimate goal of existence was to achieve unity with the divine.”

“And they did that … how?”

“By being a philosophos. A ‘lover of knowledge.’”

“A philosopher?” She rolled her eyes.

“Yeah, but not Kant or Nietzsche or some nineteenth-century effete sitting around pondering the meaning of morality. More like a natural philosopher.” She still looked dubious. “The word ‘scientist’ comes from the Latin for ‘knowledge,’ you know. So that makes you basically just a philosopher in a lab coat.”

She looked mildly affronted but gestured for him to go on.

“The philosophers studied nature to uncover the pattern that unifies creation. That pattern, they believed, embodied the wisdom of the gods. The divine will that created the world. And once they found that pattern, if they found it, they could reach the ultimate purity of the soul. They could become gods themselves.”

Ruth laughed, her patience for mysticism clearly running thin. “Sounds like unified field theory, if you ask me.” When Theo looked at her curiously, she went on with a shrug. “You know, how quantum mechanics and general relativity don’t play by the same rules. Einstein spent an inordinate amount of time trying to come up with a theory that worked for both.”

“A pattern that unifies creation, huh?”

“Yup. But he didn’t find it. No one has.” She rose to her feet, looking down at Theo pointedly. “And something tells me, despite all the library books you’ve got spread across the quad, you won’t either.”

He shrugged, trying to look appropriately sheepish.

“Theo …” she began, a suspicious frown tugging at her lips. “How is all this going to help you figure out where the Mithraists’ leader is hiding?”

Saturn … Every time Theo thought of the old man with his curved sickle he had to fight back a tide of rage. Selene’s grandfather was both the God of Time and the Pater, or “Father,” of the Holy Order of the Soldiers of Theodosius, also known as the Host. A secret cult dedicated to destroying the Olympians in order to allow the rebirth of Mithras-as-Jesus. The Host’s initiates had ki

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...