1

they’d ended up slicing her open, which was great. She was sort of hoping for a C-section. The stories Anya’s friends had shared about their incontinence, their prolapses—one of the women, Ellen, describing the way a hunk of her bladder or vaginal wall (who knows!) would slip down throughout the course of the day. Bulge. She’d framed it as a minor irritation, easy enough to poke back in, no different from enduring the day with a sock that keeps slipping beneath your heel. Except it was every day. And it was body parts. Very inside ones. Creeping out like some activated fungus. Which was why pretty soon, Ellen explained, casually, hooking an invisible hair from her mouth and tucking it behind her ear, she’d be looking into some sort of scaffolding. A mesh—interlocking her fingers, miming weight—that would hold it up for her. Like basketballs, piped in Dawn, another one of Anya’s friends who Dani had recently met, in a high school gym equipment room, remember?? Laughing, nodding. Though Ellen, Dawn, and Anya had all gone to different high schools, the equipment rooms, with their suspended basketballs and oily, low-frequency stench, were very much the same.

And Ellen, Dawn, and Anya had all heard of the mesh too. Because they all knew someone, a woman, secretly held together by it. Dani wrapped her mouth gracelessly around a blast of corn chips and wondered why the fuck no one had told her about the mesh before she got pregnant.

“Well, Elaine had a fourth-degree tear,” Anya revealed, thumbing a wayward gob of guacamole back onto her chip. Anya, in many ways the worst of them, Dani’s oldest friend, who she loved like a sister but also found unkind, judgmental, manipulative, competitive, and actually a bit racist in ways she seemed to perceive as simply good sense: “Immigrants are driving up the cost of living in the top cities, I’m sorry, but it’s true. If you come here from somewhere else you should have to start in, I don’t know, some middle-of-nowhere town that needs the economic push, you know? It’s only fair. And it’s good for everyone.”

Anya had experienced both, a C-section and a vaginal birth, and though the vaginal birth had been amazing, oh my god, it’d also left her with chronic incontinence (Do you know that I piss myself? A little bit? Every goddamn day?) as well as what the doctor referred to as sexual dysfunction, which was so severe her husband, Bill, had taken up yoga. His back, once a densely knit tapestry of chronic pain, was now limber as a river reed. We should have stopped fucking years ago, he joked, and Anya nodded readily—honestly, though, a hand on Dani’s arm, her tone edged with a conspirator’s sincerity, he’s like a different person.

By almost every metric Anya was a very Normal Woman. At the very least she engaged with the material trappings of their sex in a way that Dani had never been able to—Anya exercised regularly, or at least complained regularly about not exercising enough; she had defined triceps, lean thighs; she monitored her protein intake, and knew the difference between soluble and insoluble fiber. Anya spent time outside, her chest and shoulders tanned to a fine, freckled hide. Nails always buffed, cuticles repressed, hair a multifaceted illusion of fresh blonds. Her leggings were expensive, their crotches fortified, and she’d always, since high school, had her bikini area waxed professionally, sugared when that was the trend. Eyebrows too. Threaded now. By a woman in the mall who apparently Anya would have preferred to start her life in the prairies. Dani imagined a small farming community with perfect eyebrows, in stark contrast to the shaggy and wild wheat they sowed.

Basically, Anya was the portrait of self-care, a pursuit the mothers in the online mom forums held sacred, and another maternal obligation for all but the lucky few to fail at spectacularly.

Dani wasn’t exactly sure how she and Anya had managed to remain friends for so long other than they both liked drinking too much and had once known, intimately, the versions of one another they hated most: the raw, cruel, earnest material of their youth they’d both taken great pains to pasteurize and recast into forms more consciously selected. When Dani and Anya were alone with one another, they allowed these former selves to unfurl languorously from their facades, accessing big, true laughs and rare peace, despite having, technically, nothing in common.

“What’s a fourth-degree tear?” Dani had asked at that lunch with the mom friends, the last lunch, she didn’t realize at the time, before she would go into labor. She leaned back in her chair as though distance from the explanation might inoculate her from it. She folded both hands over her moon of living belly, protecting the little person inside too. Nine months pregnant. Almost there.

“A bad rip,” said Ellen, still chewing, clearing away nacho debris with a long pull of margarita. “Poo hole to goo hole.” She raised her eyebrows.

And maybe that’s why the C-section happened. Because Dani had just wanted it so very badly: sweating, panicked, coiled helplessly around every contraction, incapable of just letting go, of breathing, her mind’s eye yoked to Ellen’s salted lips, tight around the vowels: “poooooo hole to goooooo hole.” And the body is just such a mysterious thing, especially as it pertains to childbirth. In fact, after reading book after book about the connection between fear and pain, the orgasmic, ecstatic, rapturous birth experience, the power of visualizations—I am petals unfurling, I am huge, I am opening wide as a cave, exactly as I should, for my baby to spill without pain—one might even come to the conclusion that the body is only mysterious as it pertains to childbirth. That otherwise it’s actually pretty predictable: a system of sphincters and pipes and cables that harmonize chaos like the warming of an orchestra pit, ins and outs and organs thumping, processing fuel, petals unfurling, becoming huge, ejecting waste and sometimes life, and that was Lotte, Dani’s precious baby, who mercifully bypassed her vagina, cried only when she really meant it, and completed a truly sublime figure eight when she pressed her face into Dani’s breast to eat.

Wide awake in the hospital that first night, Dani’s facade warmed, then thinned, to accommodate her new identity, this new love. And not just for Lotte either. She loved everyone now, every human being, because they’d all been babies once. And she cried from exhaustion but also because everyone was actually so good inside.

To love something this profoundly.

It was no wonder some people were destroyed by it.

Dani spent the first two days of Lotte’s life gathering information from the nurses. What if she’s constipated? (Rub her belly, this way.) What if she stops latching? (Just keep trying, this way.) What’s the difference between spit-up and vomit? (There’s no retch to spit-up, no effort, you’ll know.) Look at her hips—are her hips too small? (I’m not sure what you mean.)

These women who answered all of Dani’s questions, who cleaned the blood that gushed from Dani’s numb nethers, who grabbed her breast and pressed it into Lotte’s face as if it were some mess the infant had left on the carpet, they somehow erased the decades of shame Dani had tattooed all over her body: flat, runny breasts and nipples too big; trunk-like thighs, coarse, forever razor-burned, even in places she never shaved! Being treated this way, like a piece of machinery designed to keep this baby alive, was the freest Dani had felt in maybe her whole life.

Clark sat in a grubby vinyl chair in the corner of the private hospital room, watching curiously as she was manhandled, ready to jump for whatever Dani or Lotte might need. Thick and dark around the eyes, maybe as exhausted as Dani but certainly less severed in half. He made a little performance of reacting to Dani’s relentless questions, hands up, head shaking, my wife, my crazy wife! But after the nurses left, he huddled up with Dani, going over the answers, greedy for more, and with new questions of his own, which, of course, Dani didn’t have the answers to, but she would soon enough, whether she found them online or through another shameless session with the next unsuspecting nurse.

They acted this way in front of people, settled into these public roles without ever really discussing it: Clark, the laid-back one, easygoing, a golden retriever of a man; Dani, the neurotic, a shih tzu or chihuahua or some other quivering abomination of nature. It was important to Clark, Dani knew, to project this particular image of masculinity: A man is calm; a man is rational. A man doesn’t fret. And Dani didn’t care if people thought she was neurotic. She was neurotic. They both were; in their truest private they were both that way, simmering with dread for the moment they had to leave the hospital room, cross the parking lot, all alone in the car with their maybe abnormally small-hipped daughter. Clark’s road rage intensified by exhaustion, by their brand-new, precious cargo. Dani hunched over the car seat, screaming at him from the backseat: Would you just fucking relax, for fuck’s sake?!

And now here they were! At home! Everyone alive and well, and Lotte about to give Dani another intoxicating shit to mark in the poop chart! Dani loved—loved—to watch Lotte take shits. The real hard work of it, when a body was this small. Tense, as though a string had been drawn tight through her face and fists and feet. Dani sat down low, legs crossed, leaned in close to Lotte, secured in her bouncer chair, offering help, rubbing Lotte’s stomach, four firm fingers clockwise along the intestine’s curve just like the nurse had shown her.

And then Lotte would embody the kinetic still of a raindrop caught in a window screen, lock in to Dani’s eyes as though she were about to upload every secret she’d borne from the womb, Dani teary-eyed—I’m listening, sweet angel, I can hear your perfect voice—and then Lotte would release a long, shockingly robust fart alongside an ooze of odorless gold. Lotte’s mouth tuning into the shape of her own tiny asshole, a cinched, roving O until it was all over. And Dani shrieked like a hysterical disciple, kissed Lotte’s feet, her hands, her head—Amazing baby! Amazing girl! You’re so strong! You’re so good!—and Lotte would accept the kisses as a dog does: intrigued, unthreatened, but not entirely sure.

This, finally, was work that Dani enjoyed. Work she was actually good at. Each day brought with it some new victory: a warm, fresh roll of fat, evidence of the hard work of breastfeeding; a smile at just the right time, proof that she’d grown a good and standard baby. When Lotte transitioned out of her newborn clothes and into her 0-3-month wardrobe, Dani felt it like a promotion, beaming with pride. For a moment she understood the thrill the witch must have felt in “Hansel and Gretel” when she’d sufficiently fattened up those naughty children for roasting.

Ten pounds, then eleven. Twelve! Which seems like nothing until it’s a squirming, bouncing, fragile twelve pounds, mass that wriggles and twists and buckles at the hinges.

Dani and Lotte, they were moving on up, into the next pay grade, where the stretches of sleep were longer, the feedings less frequent, the need less intense. And the returns—smiles and giggles and chatter and sustained eye contact—rich beyond her wildest dreams. They were becoming real humans together, for Dani a return, though, in her opinion, as an improved version of her former self, and for Lotte a whole new form.

And there was nothing better than this. Not the perilous exhaustion, of course. Not the purgatorial boredom. And certainly not the intense pressure to make everything perfect for this brand-new creature you created, the world reminding you, with what felt like renewed wrath, of what a shithole it is. But rather this—this wholesome and complete sense of meaning. It was warm, thought Dani, actually warm, places she’d been cool inside now honestly and truly warm. Finally she could stop thinking about herself, about what she had or hadn’t accomplished with her life. It didn’t matter anymore if Dani was special. Because she didn’t matter anymore. Lotte had obliterated her, released her from that suffering.

And despite being more stressed than ever at work, helming the flagship project of a brand-new office in a brand-new town, late nights, sometimes weekends, emails all the time, Clark was the most incredible dad—eager to take Lotte whenever he could, endless endurance for peekaboo and patty-cake and head-to-toe raspberries. He leaped for every diaper, scarfed his dinner so he could take her off Dani’s hands. “My mind is so calm around her,” he said one night while they watched Lotte asleep in her crib, wrapped tight as a cigar in a bamboo swaddling blanket, a gift from Anya.

This wasn’t true, of course. Clark was as troubled as ever, maybe even more so. Tricked by love. Confusing it for peace. To see him fooled this way filled Dani with the urge to kiss him. So she did. In a way she never had before. Like their intimacy mattered now. And this kiss triggered a hunger within them both, more mouth, more skin, but also more love between them. Less fighting. They loved each other, didn’t they? How could they have ever fought so much before? And was it a lot? Or was it actually just the normal amount of fighting that two humans in love must do in order to not subsume one another, actively keeping parts of themselves too prickly to be absorbed.

It was healthy to fight this much, Dani decided. Despite what the moms in the mom forums said. They were all lying anyway. Women like that were incapable of acknowledging unhappiness in their marriage, for the same reason a soldier might find it difficult to acknowledge shortcomings in the country he’d killed for.

Clark and Dani were parents now. A family. Something more sacred about the way they engaged with and treated one another. Their lovemaking a solemn act that produced little angels like Lotte, who would be looking to them as models for her future relationships. From now on there would be a terrible punishment for failing to love each other properly: having to watch their most precious treasure lock herself into the same miserable patterns that they had. Neither of them could take that, they both knew. So they agreed, tenderly, without words: We’ll never be careless with each other again.

Everything was perfect. Everything seemed perfect. It should be perfect. Dani had a beautiful baby who filled her poo charts like an absolute prodigy. She had a renewed love for her husband, even enjoyed having sex with him again, despite the warning from the forum mothers, and Anya, that a husband’s touch might trigger blind rage for a while after baby. And most of all, she’d been annihilated, blissfully, finally, by true meaning in her heart.

But of course, over the long days and the longer nights, all that began to fade. Dani’s positive connection with her body severed, her perception of it drifting back to its familiar patterns of shame and disgust—Lotte was still perfect and beautiful, but sex with Clark again became the chore it’d been before they’d started trying to conceive (TTC in the mom forums). Purpose-driven sex was a real turn-on to the women in the forums, Dani included, it turned out. The trick after baby, they said, assuming you weren’t facing the additional challenge of having been fortified with mesh, was to find a new purpose. Maintaining a happy marriage. Creating a devoted husband. Could you possibly want that as much as you’d wanted a baby? asked one of the forum moms. Try it, try it, and you may. A quote, they all knew, from Green Eggs and Ham. So they commented their LOLs. Dani lolled too, but she would never have posted it.

Many nights, sitting awake in the rocking chair, enjoying the hydraulics of Lotte’s feeding, always feeding, somehow always, endlessly feeding, Dani would scroll through the mom forums, seeking advice and reassurance from women who chronically misspelled aww as awe and called each other hon, which didn’t seem right to Dani—shouldn’t it be hun? And she could never not read it as a dig, even though she knew that many of them didn’t mean it that way.

How much Vaseline are you using, hon? Sorry hon, we chose not to mutilate our son’s genitals so I’m not sure what to do about an infected circumcision.

Well hon, why did you post at all? If you have nothing to say? Mamas please be more intentional about how you post, I’m sorry, it’s just a pet peeve of mine, all this digital clutter.

There was one particular woman, a beast called MUM2GABBY, whose posts were usually all-caps gripes about other mothers. Subjects like YOUR BABY WANTS TO LOOK AT YOU NOT THE BACK OF YOUR PHONE! And then a long rant about having spotted a mother who dared to be reading on her phone while nursing her child at the park. Other things poor Gabby’s horrible mother hated: working mothers (You HAVE a job, you’re a MOTHER NOW!), daycare before the age of three (Why even HAVE KIDS if you’re not going to RAISE THEM!), the actress Kristen Bell (DO NOT GET ME STARTED!).

Often these forums presented themselves because they contained some extremely specific phrase Dani had typed into the search bar, usually a query about one of the many infinitesimal defects that present in every human body, minor deviations introduced over three hundred thousand years of reproduction and not a big deal at all. Things like:

four or five purple veins along newborn’s temple

slightly dark cuticles newborn

purple beneath eye newborn??

Dani searched through galleries of rashes and skin conditions. Galleries of healthy stools. Unhealthy stools. Diarrhea. Spit-up.

spit-up slightly clear???

signs of pyloric stenosis

small white bump on roof of baby’s mouth

are Epstein pearls painful??

Galleries of gingival cysts.

newborn one eye a bit wonky when first waking up

breaths per minute awake baby

breaths per minute sleeping baby

breaths per minute sleeping baby SIDS???

Galleries of cyanotic newborns.

baby won’t sleep

baby won’t sleep in crib

baby won’t sleep in crib SIDS

baby only sleeps when dead—she blinked—when held

Baby only sleeps when held.

Baby only sleeps when held.

Dani’s chest tightened around her racing heart. Eyes overwhelmed with tears. She shoved her phone beneath her thigh. Bit her lips to keep from sobbing out loud.

And Lotte’s chin bounced and bounced and bounced, rhythm undisturbed.

Lotte, I’m sorry, I would never, I would never ever, ever, my love, my sweet angel baby. I don’t know why I saw that, I certainly didn’t type that. I didn’t type that. I would never, ever type that.

Feeding, feeding. Eyelids slowing. Sealing.

Content. Oblivious. No sense yet that she’d been born to a monster.

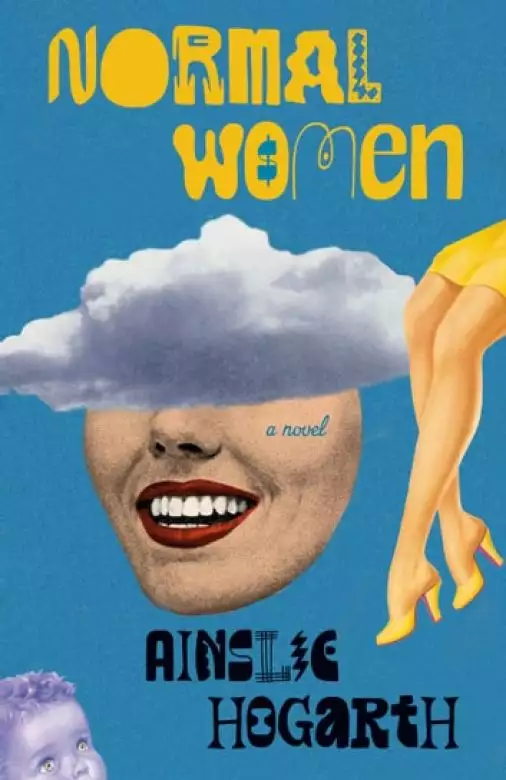

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved