- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

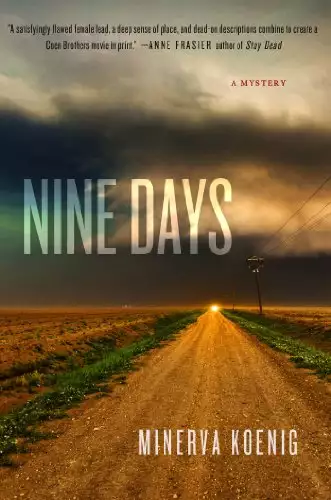

Synopsis

She's short, round, and pushing forty, but Julia Kalas is a damned good criminal. For 17 years she renovated historic California buildings as a laundry front for her husband's illegal arms business. Then the Aryan Brotherhood made her a widow, and witness protection shipped her off to the tiny town of Azula, Texas. Also known as the Middle of Nowhere.

The Lone Star sticks are lousy with vintage architecture begging to be rehabbed. Julia figures she'll pick up where she left off, but she's got a federal watchdog now: police chief Teresa Hallstedt, who is none too happy to have another felon in her jurisdiction. Teresa wants Julia where she can keep an eye on her, which turns out to be behind the bar at the local watering hole. The bar's owner, Hector Guerra, catches Julia's eye, so she takes the job. But before she can get to know him as well as she'd like, they find a dead body on the bar's roof.

The county sheriff begins trying to pin the murder on Hector for reasons that Julia discovers are both personal and nefarious. Unfortunately, the evidence cooperates, but Julia's finely-honed personal radar tells her Hector isn't a killer. She risks reconnecting with the outlaw underground to prove it and learns the hard way that she's not nearly as tough--or as right--as she thinks she is.

Nine Days, Koenig's debut, is atmospheric, gutsy and fun, and Julia Kalas is an intriguing new heroine in crime fiction.

Release date: September 9, 2014

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Nine Days

Minerva Koenig

I

"Recognize this?" says the redhead, raising a nine-millimeter pistol to my husband's face.

It's late. We're walking the scenic route home after closing the bar. Joe stops, watching the redhead's partner come around on my left side. They're both under twenty years old, with stubbly heads and slow, mean eyes.

"Sorry, guys," Joe says, showing them his handsome fuck you grin. "We're dry."

"We don't want your money, guido," the redhead sneers. "It's too late for that."

A cop car ambles through the intersection at Twentieth and B, half a block behind the man with the gun, and a familiar dread tickles the bottom of my stomach. I'm not really here, but I've been here before. I know what's coming.

My hands jump to my ears seconds ahead of the shattering blast that takes half Joe's head off, and I brace for the two slugs that are coming my way. I remember that they won't kill me. The cops will make the far corner in four and a half seconds and save my life. Not Joe's. He's already gone.

God damn it. Living through it once wasn't enough?

II

"That's gotta be her," somebody said.

I surfaced from the dream and found myself beached on the rear seat of a black Chevy SUV, blinking at the back of some guy's head. We were parked in a dark loading bay next to a bus station. Through the plate glass window, I could see a big woman dressed in a gray button-down shirt and pressed navy twills coming in from the back.

The head—Kang, his name was—folded up yesterday's Washington Post and sat tense while his partner, Buford, traded identification with the woman inside the station. I don't know what the hell they were worried about. Black tactical boots, paramilitary swagger, dark hair pulled back tight—she might as well have been wearing a sign that said COP, for Christ's sake.

After a couple of minutes, Buford turned and jerked his thumb at us. Kang and I got out of the car.

Nobody had told me where I was going—security, they said—but we had to be south of the Carolinas. The air was warm and thick, with a moist, grassy smell. Florida, maybe?

It had been forty degrees and raining when we'd left Virginia on Tuesday morning, and I'd dressed for the weather. I took off my coat as we went into the bus station, shifting my travel bag from one shoulder to the other.

The woman was bigger than I'd thought at first—close to six feet and heavily broad, the smooth column of her neck rising from her shoulders like a mast from the deck of a ship. Her eyes were a nice golden brown, but they weren't friendly.

"I'm Teresa Hallstedt," she said, giving me a frank once-over. She seemed slightly puzzled.

"Want your money back?"

"No, but you might," she murmured. No pause, like she'd had ready.

Kang guffawed and swatted the Post into my midsection. As a parting gift, I took it away from him without breaking any of his fingers. He and Buford muttered some farewell platitudes, shook hands all around, and beat it. My ears did a little victory dance. The two of them had been yammering nonstop since Knoxville.

The Amazon headed for the door she'd come through, without any more talk. I followed, liking the way she maneuvered herself—plenty of swagger and taking up space like she deserved it; none of the shrinking, minimizing mannerisms that big women so often resort to. For about the millionth time since puberty, I wondered what it felt like to be tall.

Outside, I had to stop momentarily to steady myself. The night sky, no longer hidden by the loading bay roof, blasted into infinity overhead, impossibly vast and ending at a horizon that seemed very far away and too low. A weird lifting sensation, as if I were falling upward. It felt like a stiff wind could come along and blow me straight to Canada.

"You coming or what?" the Amazon called across the empty parking lot.

Two and a half years cooped up in various secure locations with cops and lawyers had made me a stranger to the outdoors. I shook off my vertigo and made tracks for the burgundy four-door Pontiac. We buckled up and pulled out onto a narrow two-lane road. She eyed my sweater. "You want the air?"

Before I could answer, a burbling chirp sounded, and she brought out a slim black rectangle with a glowing blue face. I glared at it, irritation crawling up the back of my neck. I'm not a fan of the telephone, in any configuration. For my money, Bell attached his invention to the wall so you could get the hell away from it.

The Amazon listened, her lips compressing. "Fire there yet?" More listening, then, "Did she get a look at the guy?"

A green and white sign flashed by: AZULA, TEXAS. POP. 5,141.

"I'm about five minutes out," the cop continued into her phone. "Yeah. OK, Benny. Thanks."

She beeped the thing off and put it away, seeming to forget that I was there. I didn't remind her.

We hummed along in silence for maybe half an hour, the sparse ghosts of small houses sliding by out in the landscape; then the Pontiac slowed and rattled over a low bridge into a town square. A stone courthouse held down the patch of dry grass at its center, a couple dozen weathered storefronts huddled around it like campers around a fire. The place could have done time for cuteness if half the buildings hadn't been boarded up or vacant. I felt the thing between my ears boot up the automatic cost-benefit analysis it always runs through when I lay eyes on derelict real estate. My mood started to lift. Maybe this exile to the sticks didn't have to be the end of life as I knew it.

A thick plume of gray smoke twisted up into the sky from a building on the far corner, to our left. Two fire trucks were parked at the curb in front, and a couple of guys in full hero regalia stood on the courthouse lawn, one with a radio pressed to the side of his face. A short way off, closer to us, a uniformed cop was talking to a tiny old woman at the open driver's-side door of a police cruiser. They shaded their eyes against the headlights and stepped back as the Amazon pulled up alongside.

"Hey, Chief," the uniform said, walking over and laying his arm on the Pontiac's roof. He was maybe thirty-five—small, dark, and wiry—with a bristle of black hair growing low on his forehead. Second generation, I bet myself.

"Anything?" the Amazon asked him.

He shook his head. "911 caller gave the same description as Silvia did—Caucasian, blond, red gimme cap—but he was long gone by the time we got here." He jerked his chin at the firefighters. "First-in found point-of-origin indicators that look fishy."

"Damn it," the Amazon growled. She put the car in Park and got out.

As the cops strode toward the firefighters, the old woman—Silvia, I presumed—inched over and peered in at me. Her face was lined and folded like one of those dried apple dolls, with shiny black raisin eyes. Thin braids the color of sheet metal lay down the front of her patterned housedress.

I gave her the eyebrows, and she said, in a surprisingly deep voice, "What did you do?"

I considered telling her I'd just killed somebody's grandmother, but decided it was a little early to go off script. I hadn't even been in town for fifteen minutes.

"Nothing," I said. "I'm a friend of Teresa's."

The raisin eyes moved off my face to the suitcase in the backseat. "From where?"

"Boston," I said.

She smiled as if at a joke, and my radar went off.

"What's funny?"

The cops were back before she could get an answer out, the Amazon asking her, "Silvia, you sure you didn't recognize this runner?"

"All them white boys look the same to me." She shrugged.

The Amazon got back into the car, saying to the uniform, "Keep everybody here, will you, Benny? I'll be right back."

We bumped over the fire hoses crisscrossing the street and passed along the front of the courthouse. The Amazon nodded toward the row of buildings facing it and said, "You've got a job interview there tomorrow afternoon."

The buildings she'd indicated were all dark except for a two-story place with a row of Harley-Davidsons parked at the curb in front and a neon sign in the window reading GUERRA'S. Open at this hour, it could be only one thing.

"Get bored halfway through?" I asked the cop.

She cut her eyes at me. "What?"

"If you'd read my whole file, you'd know that I was just stop-gap help in the bar, as a favor to my father-in-law. Construction is my field, not slinging booze."

She made a face and started shaking her head before I'd stopped talking. "You're not in California anymore. Girls don't do that kind of work around here."

I gave her back the face. "But they're allowed to run the police department?"

"I'm not in hiding from a bunch of neo-Nazis who want to kill me," she pointed out. "I can afford to be weird. You can't."

Fucking cops. Everywhere you go, they're the same.

Away from the square, there didn't seem to be much of a town. We drove maybe half a mile on a curbless, pitted strip of asphalt apparently unrelated to the sporadic buildings in its vicinity, some of which might have been houses. After we turned right at a small church with a big graveyard, signs of habitation disappeared entirely except for a big white house up ahead on the right.

The Amazon stopped to let a car coming toward us exit the narrow gravel driveway before turning in. There was a young woman at the wheel, too busy keeping her beige four-door out of the ditch to acknowledge us. I felt a little zap of something come off the Amazon as we passed, but it didn't last long enough for me to classify.

We parked on a bare patch of dirt under a low-hanging tree, and I followed the Amazon up onto a long screened porch facing the driveway. She unlocked a door and flipped on the lights, illuminating an antique kitchen with a Formica dinette against the wall, between two tall windows.

"I've gotta go deal with this fire situation," she said, twisting a brass skeleton key off her ring and handing it to me. "I'll come by in the morning so we can get each other up to speed. Call me on my cell if anything needs attention before then." She scribbled on the back of a card with a green ballpoint. I took it, and she disappeared down the porch steps.

In addition to the kitchen, there was a bathroom with an Olympic-sized claw-foot tub, and a room barely big enough to contain the queen-sized bed shoved sideways against the wall under a high window. Another door faced me across the narrow space alongside the bed, but it was locked and didn't open with the key. I decided I could survive the night without seeing my living room, and tossed my stuff into the closet. Then I went out to sit on the porch steps and take another look at that sky.

III

The heat woke me late the next morning. I lay there listening to the unfamiliar silence, wondering if I'd gone deaf in my sleep. Then I remembered where I was.

Wrapping myself in the bedsheet, I got up and went into the kitchen to forage. A rattle at the apartment door sounded before I could get the refrigerator open. Figuring it was the Amazon, I opened up and found a man standing there instead.

"Sorry," he said, taking a step back. "I didn't know Teresa had rented the place already."

He was whip-thin but expansively framed, big bony shoulders pushing at the seams of his snug-fitting T-shirt, with frankly dyed black hair and light eyes that didn't quite connect with mine. He gave off sex like church incense, and I felt myself remember that a few of my favorite condoms were still floating around in my bag somewhere. I'd just started thinking about asking him in when the Amazon appeared from a door at the far end of the porch.

Her hair was wet and she wore an exasperated expression. "Don't you answer your phone?"

"I didn't hear it," I said, privately amused by the technical truth of the statement. I'd unplugged the loathsome instrument before falling into bed. An old habit and a good one.

"Hey, Teresa, is Richard around?" the guy asked her. "I need to get into the basement."

"I don't keep track of him anymore, Jesse," she said, a stain of irritation on her voice. "Let's go inside," she said to me.

He put a hand out, saying, "I'm Jesse Reed, I live upstairs."

"Julia Kalas," I replied, shaking.

"Like the opera singer?"

I spelled it and his expression went curious, his eyes hovering somewhere around my chin. "What is that, Greek?"

"It's Finnish."

The feds had fought me on it at first, but there was no way I was spending the rest of my life named Smith. It wasn't as if the name Kalas were traceable to me—at least, not by anyone I didn't want to be able to trace me when the time came. I told the feds I'd picked it out of the phone book, and when I showed them how many Kalases were listed for Boston, they let it go. For people whose job it is to be suspicious, they were surprisingly gullible.

The Amazon gave the apartment door a push. I backed up with the knob in my hand, letting her in.

"Nice to meet you," Jesse called after us. I saw him smirk as he trotted down the porch steps, revealing a pair of predatory canines.

"You want to watch yourself with that one," the Amazon said as I went into the bathroom to get dressed. "You'll be on your back with your panties on the floor before you know what hit you."

"Yeah?" I replied, curious. "Will I enjoy it?"

She made a disgusted noise. "How the hell should I know? I wouldn't touch him with a ten-foot pole."

Her eyes dropped to the two splotchy pink scars on my right side without changing, so she'd gotten at least that far into my file. I pulled on a T-shirt and checked my face in the mirror. It still looked the same.

"Who's Richard?" I asked, coming back into the kitchen.

She had coffee and filters out, and was filling a copper kettle at the porcelain sink. "My soon-to-be ex-husband. He's taking his time moving out, so you might run into him around the place. Don't let him give you any shit."

I got as comfortable as the chrome chairs at the dinette would let me. "Is he likely to offer me some?"

"He's likely to do any damned thing," the Amazon sighed, setting the kettle on the stove and lighting the gas. "Fortunately, it's not my problem anymore."

I wondered what her husband was like. Big guy. Rough around the edges, probably, to match her. "How long were you married?"

She waved it by, coming over to take the other chair. "Everything all right with the apartment?"

Some blood in the water there, I thought. Putting it on the back shelf to play with later, I replied, "I don't know—I haven't seen all of it yet. The door in the bedroom is locked, and the key you gave me doesn't open it."

"Yeah, that's my place," she said, leaning back and crossing her arms. "I split this floor into two units after Richard moved out."

I let my eyes drift around, and she pointed out dryly, "You're not gonna live here forever."

That reminded me. "There's only fifteen thousand in the bank account the feds set up. I was supposed to get fifty for the house in Bakersfield."

"The fifteen is for a car and living expenses until you can get a paycheck coming in," she said. "If you find a property you want to buy, let me know and I'll get what you need transferred down."

"Why can't I just have what they owe me, straight up?"

Her brown eyes jumped to my face, going sharp. "WITSEC's not in the business of giving habitual criminals big chunks of cash."

Again with the tone. I surveyed the backyard to give my temper time to settle. Jesse Reed was leaning against a small red pickup, talking urgently into a cell phone.

"Let's hear your backstory," the Amazon said, sounding dissatisfied. My lack of lip seemed to have thrown her off her game. Maybe she spent a lot of time with people who don't learn from their mistakes.

"I worked for your cousin Etta at her place in Roxbury," I recited, the words coming off my tongue like I'd been saying them all my life. "My marriage broke up last year, and you invited me down here to make a fresh start."

"What happened?"

I scowled at her, and she made a gesture with one hand. "I mean, what are you supposed to tell people happened?"

"Fuck if I know," I said. "I guess he ran off to Rio with his secretary or something."

"Pick a story and stick to it," she said, getting up to answer the whistling kettle. "People will ask you that—you'd be surprised."

Not as surprised as they'll be when I tell them to mind their own damned business, I thought, watching the Amazon pour. Her long hands were delicate on the kettle's porcelain handle, and there was something softly susceptible about the shape of her rounded arm, the angle of her head. I suddenly realized that she was pretty. You didn't notice it at first, with her professional gristle in the way.

"So how'd you win the federal babysitting lottery?" I asked her. "The locals don't give you enough business?"

"They can't keep an inspector down here," she said, watching the hot water sink through the coffee filter. "These kids from Washington show up thinking it's gonna be cowboys and Indians. They don't stay long."

"Why didn't they send me someplace with an active inspector?"

"You'll have to ask them, but I'm guessing it's at least partially because of my zero-tolerance policy for ‘white power' crap in my jurisdiction." She brought the pot over to the table. "I'm kind of lame on some things, I admit it, but racist gangs?" She shook her head. "Homey, as they used to say, don't play that."

My radar homed in on her vehemence, and I wondered if there were something personal behind it. She didn't look like she had any color in her blood, but neither do I. "Why's that?"

She got a couple of heavy white mugs out of the cabinet, ignoring my question. "Your interview's at one, with Hector Guerra. In case the name doesn't make it obvious, he owns the place."

"You don't give a hell of a lot away for free, do you?"

She spooned a couple of sugars into her coffee and sat down, stirring it. She didn't say anything. It was starting to piss me off.

"Seriously," I said, "do I have to take this job?"

Her doe-lashed eyes flashed up at me, but she kept quiet. I gave her points for waiting out her temper this time.

"There's not a lot of work around here," she said when she finally spoke. Her voice was calm and even. "Hector's doing me a favor, giving you dibs on this bartending gig. I'm not gonna be very happy if you jerk him around."

"What if I want to do something for a living that I'm actually qualified for?"

"Like what, dealing guns and drugs?" A little crack in the calm and even.

I frowned at her. "We never dealt drugs."

"They're two ends of the same stick," she snapped. "You deal in one, you deal in the other."

I shut up and pulled my coffee over, just for something to do while she got a grip. A couple of minutes without talking, then she said, "Look, you helped your husband and father-in-law sell those black market pieces, and you laundered the profits through your construction books. That doesn't exactly inspire confidence in somebody responsible for the public safety." She tapped the Formica table with the tip of her index finger. Her nails were tastefully manicured, with a subtle pink polish. "You need to prove to me that you can be a law-abiding, responsible citizen. Holding down this job for a while is an easy first step."

"Helping the feds shut down that bunch of Ladders didn't buy me anything?"

She fixed her wise brown eyes on me. "Yeah, it bought you this chance. Don't fuck it up."

Before I could reply, she caught sight of her watch and got up, gulping her coffee. "I gotta go."

"Wait a minute," I said as she headed for the door. "How am I supposed to get downtown?"

"You can walk it in half an hour," she threw over her shoulder. "Make sure and give yourself enough time."

I waited until she was out of visual range to flip her the bird. Then I got up and poured out the coffee. I hate that shit.

IV

Around noon, I put my sneakers back on, wishing I had something a little nicer to wear. Hearing myself think that told me I was more stressed out than I'd realized. I've always been a pretty spectacular failure at femininity, what with the fat thing, the brain that won't shut up, and the obsession with machines and buildings; I'd successfully thrown in the towel after my torture-chamber puberty, and discovered that hauling plywood and Sheetrock instead of a purse didn't change anything except the way other people treated me. I only ever worry about how I look anymore when something else is bothering me. Right now, that included just about everything on the planet.

Chapped at having to think about it, I considered what to do with my hair. I'd worn it short and dyed dark since bailing out of Tucson for California after high school, but the feds had advised me to change my appearance as much as possible after going into protection, so I'd been letting it grow. It was past my shoulders now, an unruly pain in the ass with sprigs of gray silvering up its natural dead-grass color. I didn't mind the way it looked, but in this heat it was kind of like wearing a fur coat in hell, and putting it up required the kind of decision making I'd cut it off to avoid. I finally just twisted it up on the back of my head and clipped it there. It didn't exactly scream professionalism, but maybe failing my job interview would make it easier to talk some vocational sense into the Amazon.

On my way out, Jesse Reed popped into my memory, and I checked the stone foundation for basement windows. Sure enough, there they were, which I hadn't expected. Every now and then I'd come across a basement in Bakersfield, but they were rare because of the shallow frost depth, and I couldn't imagine that it got much colder here. I stopped to examine the house more closely. It was two stories with a steeply pitched roof—Victorian, if you held a gun to my head—easily a hundred years old or more. It was in pretty good shape, but needed a new roof and some repointing on the foundation masonry and chimneys. Looking at it made my hammer hand itch.

At the end of the driveway, I paused under a solitary tree to absorb some shade. Flat landscape covered in yellow grass spread almost treeless to that weird, low horizon in all directions, knuckling under to a sky so bright that it was almost white. The few buildings that dared stand up under it did so timidly, keeping low to the ground and far away from their neighbors. I could smell cows, but didn't see any. Up the road to my right, a sunburned Cadillac DeVille slanted off the pavement, bumper-deep in the weeds. To the left, toward town, the white clapboard church where we'd turned the night before stood to one side of a blockwide cemetery surrounded by a fence of heavy black chain slung between low granite piers. It seemed miles away.

I started walking along the gravel shoulder, wondering if the Amazon had warned my prospective employer that I'd be on foot, overdressed, and underqualified. Resentment stung the back of my throat again. I knew my way around a saloon, but not so well that you'd want to pay me for it. I'm good at reading people, and when Joe and Old Pete, his dad, had a buyer they weren't sure about, they'd stick me behind the bar so that I could observe on the down low. I'm not psychic or anything—just better than average at reading the unconscious, nonverbal information that every human being on earth throws out. It's a nice skill to have, but probably not worth its weight in actual bartending experience.

By the time I got to the church, I was giving serious thought to just telling Guerra, straight up, that I didn't want the job. The Amazon wouldn't like it, but what could she do? Tattle on me to WITSEC, I guess, but surely they'd prefer I not make an incompetent spectacle of myself. I was supposed to blend in.

A couple of the church's granite fence piers were in the shade, and I stopped to sit down and let some sweat dry. As I did so, the DeVille I'd seen parked in the ditch down the road from the Amazon's house appeared on the other side of the cemetery. It had dark-tinted windows, so I couldn't see who was driving. The back of my stomach went cold when it slowed and then stopped, watching me across the tombstones like a sheet-steel animal of prey.

My brain snapped off and I dropped into a high, cold landscape of pure-body survival that slipped on like a familiar custom-made garment. The government shrinks had decided this was some kind of psychological damage from the shooting, but it's a trick I've always had up my sleeve, and no way was I interested in being cured of something that's kept me alive for thirty-eight years and made me a damned successful criminal. The split seconds I save by not having to run everything through my prefrontal cortex are probably the reason I'm still here and Joe isn't.

I wasn't sure how long I sat there before the DeVille finally gunned its motor and sauntered insolently away, turning toward downtown on the other side of the church. It was still early afternoon, but it could have been a year later. I waited until my thought processes were working again, then got up and crossed the graveyard, putting some speed on it.

V

When I came into the northwest corner of the square about ten minutes later, the Cadillac was parked in front of a shopworn department store half a block straight ahead. I stayed on the sidewalk in the shade of a tall stone building on my right, keeping my eyes open while I decided what, if anything, to do.

In the daytime, the square looked almost monochromatic, most of its color bleached out by the hard white light. Some of the buildings had wood awnings that hung out over the sidewalk, but the sun seemed to blast right through them, sucking all the visual detail out of the window displays. The ones there were, anyway. I counted up the number of vacant properties: eighteen of twenty-four. Still showing signs of life were the department store, a corner store directly across the street from where I was standing, the courthouse, the bar, an indeterminate business a couple of doors down, and a large stone building diagonally across the intersection from that. Everything else seemed coated in graveyard dust, still and blank, like blind mice. The marquee above the theater on the other side of the courthouse still advertised a first-run matinee of Pulp Fiction, the plastic letters yellowed and crooked.

While I was thinking about Uma Thurman taking a needle in the chest, the old lady who'd talked to me at the fire the night before came out of the department store, a package under one arm. She got into the DeVille and drove off, in no hurry.

I stood there flat-footed for a minute, trying to decide whether I had something to worry about, or if I were overreacting to a normal level of local curiosity because of my circumstances. After ten minutes passed with the radar liking neither answer, I walked down and went into the department store. Bells hanging from the inside handle jangled as the door swung shut.

"I'm coming!" a faint voice called from somewhere out under the fluorescent lights.

The place smelled a thousand years old, even though it was probably only eighty or so. The mannequins in the front window were plaster, with hairstyles from the early '60s. I fingered a rack of blouses near me. They had a slick, plastic feel.

"Plus sizes are in the back," rasped the pint-size man in bow tie and horn-rims who materialized at my elbow. He was about the same age as the building, narrow-shouldered and wide-hipped, with strands of still-dark hair plastered back over his pale skull.

"Great, another segregationist," I muttered.

The old man scowled and withdrew his left hand from the pocket of his pleated gabardine pants. Only there wasn't any hand there, just the healed-over end of his wrist, which he shoved into my face. "This I lose to the worst racist in history so you can come in here calling me names?"

"I meant the clothes," I said, forcing myself not to flinch. "The bigger sizes are the same styles as all the other stuff, so why do they need their own section?"

He lifted his chin and examined me through the bottoms of his bifocals, pursing his lips. I paused to make sure he wasn't winding up to throw me out, then added, "Nobody likes being shoved to the back of the bus."

He stuck his wrist back in his pocket, still scowling. "Interesting pitch. What line are you with?"

"I'm not a sales rep," I said. "Just an easily annoyed fat broad who's done too much shopping."

He made a dismissive motion with one shoulder, eyeing me thoughtfully, then said, "What suburb of Los Angeles are you from?"

My stomach jumped. "What?"

The old man grinned, like he'd just done a magic trick, and tugged his right earlobe. "Still know my accents!"

"You might want to get a checkup," I told him. "I'm from Boston."

His expression turned skeptical, and I changed the subject before he could ask any more questions. "Listen, the lady who just left, Silvia something. Do you know her?"

Before I'd gotten my teeth back together, he sprang at the rack of clothes behind me, crying, "Those gonif kids!"

He yanked a satin slip off the rack, holding it out to show a long rip in the shiny pink fabric. It had clearly been slashed.

"That's the fourth one this week! What's the point of tearing up my goods and just leaving them here, will you tell me that?" He stalked over to the cash register by the front door, kvetching, "For their trouble, they could just steal the damned things."

"There's not much fence value in clothes," I said before I could stop myself.

He gave me a look, and I added quickly, "I'm a friend of Teresa Hallstedt's. I guess she's kind of rubbed off on me."

I thou

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...