- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

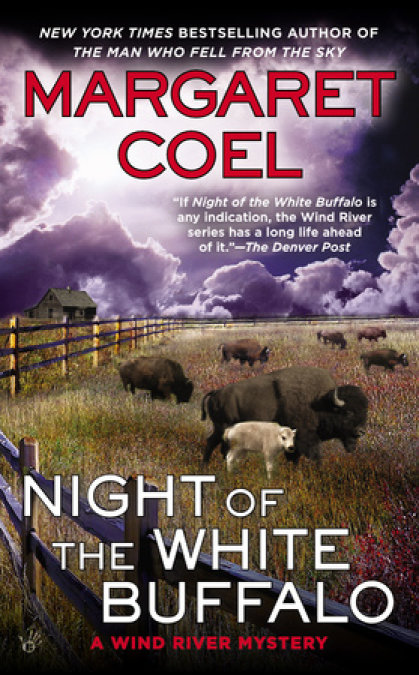

New York Times bestselling author Margaret Coel returns to the Wind River Reservation with Arapaho attorney Vicky Holden and Father John O’Malley investigating a mystery overshadowed by a mythological miracle…

A mysterious penitent confesses to murder, and then flees the confessional before Father John can identify him. Two months later, Vicky discovers rancher Dennis Carey shot dead in his truck along Blue Sky Highway. With the tragic news comes the exposure of an astonishing secret: the most sacred creature in Native American mythology, a white buffalo calf, was recently born on Carey’s ranch.

The miraculous animal draws a flood of pilgrims to the reservation, frustrating Vicky and Father John’s already difficult investigation as they try to unravel the strange events surrounding both Carey’s murder and the recent disappearances of three cowboys from his ranch.

It could be coincidence, given a cowboy’s nomadic life, but Vicky doesn’t believe in coincidences. And at the back of Father John’s mind is the voice from the man in the confessional: I killed a man…

Release date: September 2, 2014

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Night of the White Buffalo

Margaret Coel

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

CONTENTS

1

Late June, the Moon When the Hot Weather Begins

THE CONFESSIONAL WAS warm and stuffy. The round light in the ceiling shone on the pages of the novel he was reading and radiated heat around the small area. He could hear the wind picking up outside, the June beginnings of the hot, dry winds that would scour the Wind River Reservation all summer. A cottonwood branch scratched at the corner of the church like an animal nibbling at the stucco.

Father John Aloysius O’Malley flexed his legs in the cramped space and checked his watch. Ten minutes before five. Confessions ran from three to five every Saturday afternoon, and the last penitent had left twenty minutes ago. He had heard the church door open and close, had felt the swish of fresh air wafting into the confessional through the slats on either side. Usually the same handful of parishioners came with a litany of the same sins. Got drunk. Yelled at the kids. Had impure thoughts about the next-door neighbor. Forgive me, Father.

He hadn’t heard anyone else enter the church, known as the new chapel the Arapahos had built at St. Francis Mission almost a hundred years ago, after the old chapel had burned down. He closed the Craig Johnson novel he was reading—Wyoming setting, people and places that seemed true and real—and switched off the light. Immediately the confessional felt cooler, or at the least not as warm. He had heard confessions at St. Francis Mission on the Wind River Reservation for more than ten years, longer than he had imagined he would be here. Six years was the usual assignment for a Jesuit, then on to a new place, new people, before a priest could become too attached, too set in his ways, too much at home.

He was at home with the Arapahos, a Plains Indian tribe he had once thought of as a footnote in a history book. Strange that he should be in this place. God worked in mysterious ways. Years of struggling with the thirst, in and out of rehab, stumbling through life teaching, or pretending to teach, in a Jesuit prep school in Boston. Then the assignment to an Indian reservation in the middle of Wyoming. He’d had to look up the place on the map. He had no idea where he was going. To the middle of nowhere, to the ends of the earth.

Father John got to his feet and was about to head out when the door to the penitent’s side on his left opened. He sat back down. In the dim light he watched the large, muscular figure folding himself downward on the other side of the screen. The kneeler creaked and groaned; a little tremor ran through the wooden confessional. The man wore a dark cowboy hat pulled low over his eyes. He propped his elbows on the ledge and dipped his face into his hands. He looked like an immense, dark shadow. Sharp smells of tobacco, whiskey, and perspiration trailed across the screen.

“You there, Father?” He had the roughened voice of a man who spent his days in the wind.

“I’m here.”

“Can’t remember what I’m supposed to do. It’s been a long time.”

“Start with what’s bothering you. What brought you here?”

The man didn’t say anything for several seconds. His breath came in quick, shallow spurts, as if he were trying not to cry. Finally he said, “I come for forgiveness.”

“What are your sins?”

“I committed murder.”

Father John felt as if he had taken a punch in the gut. On the other side of the screen, inches away, knelt a killer who wanted forgiveness. He thought he had heard almost everything in the confessional or in his office during counseling sessions. Adultery, robbery, theft, all kinds of violence against fellow human beings, even rape. He had heard it all. But no one had ever confessed to murder. “How did it happen?”

“I know what you’re doing. You’re looking for some way to forgive me. Defend myself? Defend somebody else? It wasn’t like that. I did it on purpose, what they call premeditated murder.”

“Why did you do it?”

“I didn’t have no choice.”

“We always have choices.” Father John tried to recall any recent unsolved murders on the rez. There weren’t any.

“Maybe in your world. I come from nothing.” The man was quiet for a moment, as if he had sunk into another time. “Lucky to get a bologna sandwich when I was a kid. Lived out of a truck. Dad always on the move trying to stay ahead of the law, until he took off. Left me and Mom and the truck, so Mom picked up waitress jobs, which wasn’t so bad. Least we got some food. Took off when I was fourteen, been on my own ever since. What I got I worked hard for. I been trying to hold on, and everything was gonna go away.”

“Did the man you killed steal from you?”

“It wasn’t nothing like that. Why did I think you’d understand?”

“I’m trying.”

“It was premeditated, okay? Get that in your head.”

“What do you expect from me?”

“I told you. Forgiveness.”

“Are you sorry for what you’ve done?”

“Sorry? Like I said, I had no choice. Why should I be sorry for something I had to do? Only one thing . . .” The man drew in a long breath and plunged his face deeper into his hands until only the crease of his cowboy hat was visible. “It’s like there’s no more sleep for me. I close my eyes and I see his face, the way he goes all pale when I lift the rifle, the way he tries to turn around, like he’s gonna run away from a rifle. I know the thoughts going through his head, like I’m thinking them myself. We could’ve been the same man, killer and victim.”

Father John waited a moment before he said, “There’s nothing I can say that you haven’t already figured out. You know what you have to do.”

The man was rocking back and forth, shaking his whole body. “No police.”

“You know it is the only way to help yourself.”

“Help myself to prison.”

“Acknowledge what you’ve done. And accept your just punishment. Ask God for forgiveness.”

“That’s what you’re supposed to do. Tell me God forgives me. Go in peace. Go sleep. Say a Rosary or something. Isn’t that what confession’s all about?”

“Pray very hard for the courage and the strength to accept responsibility.”

“I don’t know why I come here.” The kneeler groaned as the man shuffled his weight back and forth. “It’s not like when Mom dragged me to some two-bit church in a flea-bitten town in Arizona or Nevada or someplace. She used her spit to wipe up my face and smooth my hair. ‘Tell the priest your sins and you’re gonna be forgiven and everything’s gonna be okay for us,’ she said, ‘’cause God knows we’re sorry for whatever we’ve done, like getting mixed up with that sonofabitch you think was your father and following that no-good all over creation. I’ll say I’m sorry for doing that, and you can say you’re sorry for back talking me all the time and being so lazy when I need you to help me out.’ So I’d go into the confessional and tell the truth. How I beat up a kid in the school yard, stole money out of Mom’s purse, smoked a joint. The priest said, ‘Don’t do that again. Make an act of contrition. Say three Hail Marys. Your sins are forgiven.’”

“Do you know about atonement?”

“What?”

“It’s not enough just to say we regret our sins.”

“I don’t regret what I had to do.”

“But you know what you did, taking a human life, was a terrible thing. Deep inside yourself you know that, and that’s why you can’t sleep. You are going to have to come to terms with what you did. You have to begin to regret it and acknowledge it.”

“How’s that gonna atone for anything? How’s that gonna make up? The guy’s still dead.”

“Until you acknowledge your guilt, you won’t know. But God will give you the grace and the strength to know what might be done.”

“God, what a bunch of crap. I never should’ve come. I’m outta here.” The dark figure on the other side of the screen started to rise, and the wood creaked and shivered. He swung around, as if he might burst through the closed door, splinter the wood, send it flying across the vestibule.

“Hold on.” Father John got to his feet and flung open his own door, but the tall, dark figure in blue jeans and dark shirt was already across the entry. Lifting his right arm, as if to block a tackle, he pushed the door open and plunged outside. The door slammed shut, rocking on its hinges.

Father John took the entry in a couple of steps and ran outdoors. He stopped on the concrete stoop, unsure of which way to go. The quiet of a Saturday afternoon suffused the mission. No vehicles about. Only smears of boot tracks in the hard-packed ground below the concrete stairs. The yellow stucco administration building on the other side of the narrow dirt drive, the old stone museum at the bend of Circle Drive, the redbrick residence on the far side of the field of wild grass, all looked like a still life painting. The wind scythed the grasses and whistled in the branches of the cottonwoods scattered about the grounds.

He took the steps two at a time and crossed to the corner of the church. The dirt drive that ran past Eagle Hall was empty. At the far end stood the thicket of cottonwoods, sage, and willows that bordered the Little Wind River at the edge of the mission. Clouds of dust and tumbleweeds rolled down the drive.

No sign of the big man in the dark cowboy hat. A killer. Blown away on the wind like a ghost.

2

August, the Moon of Geese Shedding Their Feathers

THE SUN HAD dropped behind the Wind River range two hours ago, but the day’s heat locked onto the blue shadows and the starlit darkness that spread over the reservation. Parallel flares of yellow headlights stretched ahead on Blue Sky Highway. Vicky Holden rolled the passenger window down a couple of inches. The moving air felt warm on her face. Adam had turned the air conditioner on high, but she preferred the fresh air with the familiar smells of sage and the gritty dryness of the blowing dust.

“You did a great job.” Adam turned his head in her direction, a quick, perfunctory movement, then went back to staring out the windshield.

Vicky wasn’t sure about that, but this handsome man, this Lakota lawyer behind the wheel of a new BMW, didn’t give out compliments freely, not even to her. Had she stumbled in her talk to the women students at the tribal college about careers in law for Native people, especially women, Adam would have been the first to tell her. She appreciated his honesty; it helped to ground her, keep her on track.

She had been late leaving the office in Lander this afternoon. An unexpected client had walked in the door, and she was unable—as Adam always told her—to turn away Arapahos from the reservation who happened to find their way to her office and venture inside, nervous, hands shaking, blanched looks on dark faces. Never been to see a lawyer before. Not sure of what to say or do. Only certain they had been caught up in the vast, impersonal, and rigid world of the white man’s law and knowing they needed help.

She had said, “Come in. Sit down. Tell me your name.”

The woman was Arapaho, in her twenties, close to the age of Vicky’s own kids, Susan and Lucas. She set an infant’s car seat on the floor and made her way into Vicky’s private office, cuddling a small infant in a blanket that looped around one shoulder into a big knot at her waist. A city Indian, as Susan and Lucas had become. Vicky had grasped that fact immediately. Married to a warrior from the reservation, learning the old ways, trying to connect somehow with an inscrutable past that was hers and not hers.

“Mary. Mary Red Fox. He’s cheating on me, my husband, Donald.” She had a low, breathless voice. “I need to get out. He says I can go anytime I want. Pack up, take what I came with, which was nothing except the clothes on my back, leave everything else. Leave my baby. He says that’s the way it was with the people. Kids go with the father, and he can have as many women as he wants.”

Vicky sat down at her desk across from the woman. The part about polygamy had some truth to it in the Old Time, usually for the chiefs and headmen who could afford more than one wife and needed several wives to handle social obligations: feasting the leaders of other tribes, feasting the white men invading the plains in never-ending streams of wagons. Donald Red Fox was wrong about the rest of it.

“In the Old Time,” Vicky said, pulling the memories out of the long ago—sitting around the kitchen table in her grandparents’ little house, listening to stories of how it used to be—“children belonged to their mothers and their mothers’ families. In any case, this is now, and no judge is going to separate you from your baby unless . . .” She left the rest of it unsaid. Mary Red Fox didn’t need to be told that if there were any evidence she was an unfit mother, the court would award custody to the father. The girl was upset enough. Forehead wrinkled, little beads of perspiration popping in the creases. She had left the reservation and driven to a small brick bungalow on a corner in Lander with a sign in front that said VICKY HOLDEN, ATTORNEY-AT-LAW. It had taken courage.

Through the beveled-glass doors that separated her office from the reception area, Vicky saw the outside door open and close. Adam Lone Eagle paced back and forth, casting impatient, distorted glances through the glass. His boots made a swishing noise on the carpet.

“I wish . . .” Mary bit at her lower lip and bent her shoulders around the infant, who was making little mewling sounds. “I wish I didn’t still love him. It wouldn’t hurt so much, leaving him.”

“Any chance of working on your marriage?” Divorce was final, like a death that came after a long illness. What was left was guilt and wondering and second-guessing. The scars from her own divorce from Ben Holden felt like ridges of inflamed tissue deep inside her. “Have you tried counseling? Would your husband agree to go?” Probably not, she was thinking. An Arapaho warrior with a stranger, most likely a white man, telling him what to do?

“I don’t know.”

“Father John O’Malley at St. Francis Mission is very understanding and sympathetic. Practical,” Vicky added. There were cases when Father John had advised her own clients to get a divorce, for the sake of their lives, for the sake of their children.

“I can ask him.”

Adam was still pacing, still shooting glances through the beveled glass. It had taken another ten minutes for Vicky to explain that if counseling didn’t work, the woman should come back. They could start divorce proceedings. “Do you have family?”

“In Denver.”

“You might want to think about going to them before your husband is served with the divorce papers.”

Mary Red Fox had nodded, pushed herself to her feet with the precious bundle tied to her chest, and asked how much she owed.

“We’ll see how things go.”

* * *

NOW ADAM SAID, “Looks like somebody’s in trouble.”

Vicky stared beyond the headlights flashing over the asphalt at the dark hulk of a truck pulled off to the side of the highway. “Probably drunk,” Adam said, a musing, perfunctory tone in his voice. She realized that another truck—large and black—stood in the shadows beyond the parked truck.

Headlights burst into the darkness as the black truck swerved into a U-turn and shot toward them, weaving into their lane. Adam stomped on the brake pedal, sending the BMW skittering toward the borrow ditch as the truck sped past. Vicky watched the taillights flare like red firecrackers in the side mirror.

“Jesus. What the hell was that?” Adam drove slowly, tentatively, as if he expected the dark phantom of yet another vehicle to rear up in front of them.

Vicky rolled down her window and leaned outside. Something wrong about the skewed way the parked truck sat alongside the ditch, rear tires sloping downward, as if the driver had stopped suddenly and unintentionally. As they drove past, she caught a glimpse, like a reflection in a mirror, of a man slumped over the steering wheel, off balance as if a strong wind might push him backward onto the seat.

“He needs help, Adam.”

“We don’t know what just went down here. Could’ve been a drug deal.”

“Stop, Adam. Please. We have to see if he’s okay.”

“Vicky . . .” Adam shook his head, braking lightly, finally bringing the car to a stop. He shifted into reverse and, turning to look past the driver’s window, steered backward, then veered to the right and pulled in where the other truck had stood. “What do you think you saw?” He was looking into the rearview mirror, studying the truck behind them.

“The driver looks sick or hurt. He’s alone.”

Adam leaned past her, opened the glove compartment, and withdrew a small black pistol that gleamed in the dashboard lights.

“What are you doing?”

“Stay here.” He opened the door and got out.

Vicky yanked at her handle, pushed the door open, and jumped onto the slope of the borrow ditch, holding on to the door to steady herself. Adam had already closed the narrow space between the rear of the BMW and the front of the truck, the pistol tucked into the back of his blue jeans, the grip riding above his belt.

“Go back.” The words came like a hiss of steam over his shoulder.

Vicky was beside him, staying in rhythm with his footsteps toward the driver’s door, her gaze fastened on the head propped sideways against the steering wheel. They were still a few feet away when she saw the hole in the man’s forehead, the wide eyes fixed and blank, staring out the opened window.

“He’s been shot.” Adam stepped in front of her, as if to shield her from the sight. She felt the pressure of his arm on hers. “Let’s get out of here.”

“We have to get help.”

“The man’s dead, Vicky.” She looked back as Adam turned her around and began pulling her along the asphalt. He was right. Death had its own stillness.

She yanked herself free, hurried ahead to the BMW, grabbed her bag off the floor, and began rummaging for her cell phone. Tapping in 911, she started back to the truck. Adam blocked the way, like a cottonwood that had materialized on the highway. An intermittent sharp bleeping noise sounded in her ear.

“Get into the car.” A little shock ran through her as Adam grasped her arm and started wheeling her backward. “We have to get out of here.”

“What is your emergency?” A disembodied phone voice.

Vicky twisted herself free. “A man’s been shot on Blue Sky Highway.” Vicky could hear the frantic pitch of her voice. “South of Trosper Road. He’s in a . . .”

“Ford,” Adam said.

“Dark Ford truck pulled over in the southbound lane.”

“I’m sending the police and an ambulance. What is your name?”

“Vicky Holden. I’m with Adam Lone Eagle. We are attorneys in Lander.”

“The police will want to speak with you.”

“We will give our statements tomorrow,” Adam said, as if he were part of the conversation, an arm around her shoulders now, urging her back to the car.

Vicky pressed the off button. “We have to stay with the body.”

“For godssakes, Vicky. We don’t know what happened. There’s been a number of random shootings on highways on the rez. The shooter likes firing at pickups and trucks for kicks. Now he’s finally killed somebody. You want to wait around for an hour in the darkness until a patrol car arrives? How do we know the shooter wasn’t in the other truck? Ran this guy off the road, walked back, and shot him. What if the shooter decides to come back, make sure the guy is really dead? We’d be like sitting ducks out here in the middle of the rez. Christ. You want us to be the next victims? Let’s get out of here.”

He was right, she was thinking. Realistic, looking ahead, the pistol tucked into his belt. And yet, it was wrong. She swung around and faced him. “I’m staying with the body.”

“It’s crazy and dangerous.” Adam tossed his head about, taking in the darkness that stretched away from the highway. They might have been in no-man’s-land, somewhere on the moon, a killer watching them, waiting. Or making a U-turn on the highway, on the way back. “You can’t help him. He’s dead. No one can help him.”

“Have you no respect?” Someone always stayed with a body until the body was buried. The dead were never left alone. Wasn’t that true of the Lakota, as well? Where had Adam lost the way?

“Cops will prowl around the area, look for casings, bullets, footprints. They don’t need us messing up things.”

“Go on, if you want.”

“What are you talking about? Leave you here alone?” He did a half turn, and for an instant Vicky thought he might walk away. Leave her in the darkness with the body.

He turned back. “It doesn’t make sense, Vicky. It’s foolish and risky.” He was still glancing around at the darkness. “We could be here the rest of the night answering questions, giving statements. Is that what you want?”

“I told you, you can go on.”

Adam was shaking his head, a slow, tense motion of resignation and bewilderment. “We’ll wait together.”

3

THE SOUND OF a ringing phone came from far away. Father John fought his way to the surface of consciousness and propped himself up on one elbow. A bluish light pulsated in the cell phone on the nightstand, the ringing sharp and persistent. Yellow numbers glowed across the top: 12:46. He picked up the phone and slid the tip of his finger along the button. “Father John,” he said.

“Art Banner here.” The voice had the snap of a whip. Father John felt the muscles in his stomach tighten. The chief of Wind River Law Enforcement would not call St. Francis Mission in the middle of the night unless something terrible had happened.

“What’s going on?”

“White man that raises buffalo off Trout Creek Road was shot on Blue Sky Highway this evening. Clean shot in the middle of the forehead. Killed instantly, the coroner says. Thought you might know him. Dennis Carey.”

Father John drew up a picture in his mind of the tall, big-shouldered cowboy with the bolo dropping from the collar of his buttoned-up shirt, serving buffalo burgers at every powwow, every celebration on the rez. His wife, small and attractive with reddish fire in her hair and a white, grease-smeared apron draped in front of her, flipped the burgers on a charcoal grill in the back of the booth. They weren’t parishioners, but a couple of times this summer Dennis had stopped by the mission with packages of buffalo meat. Something on the man’s mind, Father John had thought, but when he’d invited Dennis to have a cup of coffee and chat awhile, the man had made excuses. Had to get back to the ranch, mend the fences, haul hay out to feed the buffalo herd. Both times he had bolted away, leaving Father John with the unsettled feeling there was something painful and sad and hard to talk about.

“I’ve chatted with Dennis and his wife a few times,” he said. “Ordered buffalo burgers at the powwows. Dennis brought buffalo meat to the mission.” He was barely acquainted with the man, he thought. Two white men from outside the rez, from a different culture, from different places, planted on a reservation. White men among Arapahos and Shoshones. Probably the reason that Banner, an Arapaho himself, assumed he would know the man.

“We’ll be here for a while yet, then I’ll head over to the ranch to notify Carey’s wife.”

“I’m on my way.”

* * *

COOLNESS SLICED THROUGH the night air, the day’s heat having receded ahead of the wind blowing off the high peaks of the Wind River mountains. It was the first Monday in August, the Moon of Geese Shedding Their Feathers, as the Arapahos kept time. He flipped on the CD player on the seat next to him as he drove around Circle Drive, past the old mission buildings, quiet sentinels from another time bathed in shadows. The white steeple of the church rose overhead, gleaming in the moonlight. The music of La Traviata filled the cab, drowning out the shush of the wind over the half-opened windows. He had been back with Verdi lately, the arias beautiful and familiar. Like reconnecting with an old friend.

He drove through the tunnel of cottonwoods with thick, heavy branches arching the road and turned left onto Seventeen-Mile Road. Another death, he was thinking; another murder. There had been so many senseless deaths in the decade he had been at St. Francis. An important part of his pastoral mission, tending to the dead and to those left behind. It never got easier. Never routine.

The reservation seemed suspended in time, as if life had stopped for the night. The flat, open plains ran into the darkness, small houses popped up here and there alongside the road, an occasional light flared in a window, and shadowy objects—pickups sloped sideways with missing wheels, swing sets and abandoned refrigerators and cartons—lay scattered about the dirt yards. Only a few other vehicles on the road. Taillights flickered ahead, and an occasional pickup passed in the opposite direction.

An uneasy feeling, almost as if he were being watched by invisible eyes, had settled over him. The rancher had been shot in the forehead, Banner said, killed instantly. There had been several random shootings on the highways in the past year, but Carey’s death looked like a premeditated killing. He could still hear the cool, certain voice of the man in the confessional almost two months ago now, the words acid-burned into his mind. It was premeditated, okay? Get that in your head.

The man had killed someone, and yet no murders had been reported on the rez in several months before the man had come into the confessional. If he was telling the truth, the body of his victim might be anywhere. In one of the dry arroyos, in a mountain cave or rock pile. In the Old Time, Arapahos had buried people in the rock piles on the mountain slopes, covered the corpses with boulders to protect them from wild animals. Is that what the killer had done?

Or he could have committed the murder somewhere else. Miles away from the reservation, a different county, a different state. Anywhere. Then why had he found his way to a mission on the reservation?

The man was still out there someplace. He could still be on the rez, driving the roads, mingling with the people. Now someone on the rez had been killed.

What if the man in the confessional had shot another victim? He hadn’t asked the man if he planned any more murders. He should have asked, and that regret had kept him awake night after night. The seal of the confessional was inviolate; he could never betray the penitent. Yet he could have talked to him, tried to convince him to go to the police. He would have offered to go with him. He had gone after the man. Walked down the dirt drive between the church and the administration building, desperate to catch a glimpse of him somewhere. But the man had disappeared into the thick stand of trees along the Little Wind River; there was no other explanation. In the middle of sleepless nights, he had imagined the killer watching him walk back and forth from behind a cottonwood, Father John searching and calling out: “Where are you? Come back. Let me help you.”

Laughing at him, perhaps, except that Father John didn’t think so. Something about the man—the tension of an internal struggle, a deep-seated regret he couldn’t acknowledge, and a need for forgiveness so profound it had driven him to the confessional—made any kind of joy or laug

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...