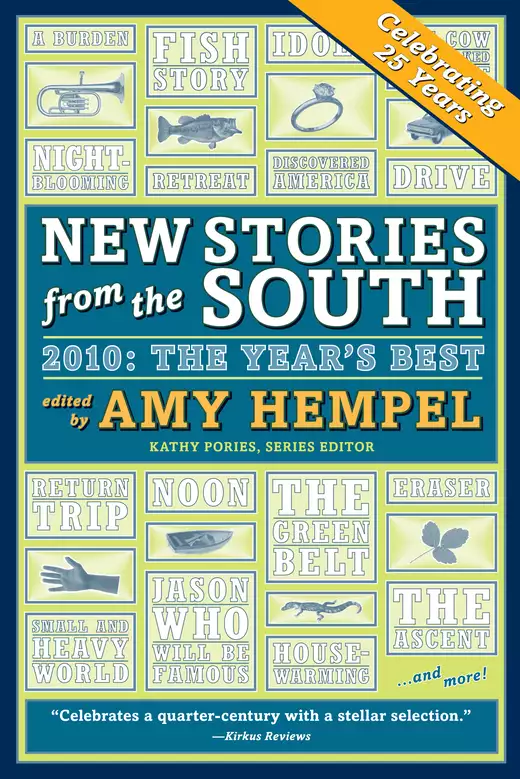

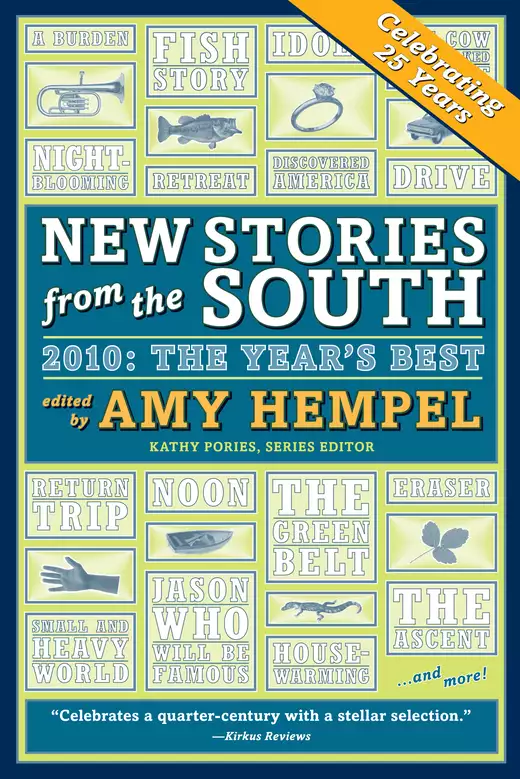

New Stories from the South 2010

Available in:

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Over the past twenty-five years, New Stories from the South has published the work of now well-known writers, including James Lee Burke, Andre Dubus, Barbara Kingsolver, John Sayles, Joshua Ferris, and Abraham Verghese and nurtured the talents of many others, including Larry Brown, Jill McCorkle, Brock Clarke, Lee Smith, and Daniel Wallace.

This twenty-fifth volume reachs out beyond the South to one of the most acclaimed short story writers of our day. Guest editor Amy Hempel admits, “I’ve always had an affinity for writers from the South,” and in her choices, she’s identified the most inventive, heartbreaking, and chilling stories being written by Southerners all across the country.

From the famous (Rick Bass, Wendell Berry, Elizabeth Spencer, Wells Tower, Padgett Powell, Dorothy Allison, Brad Watson) to the finest new talents, Amy Hempel has selected twenty-five of the best, most arresting stories of the past year. The 2010 collection is proof of the enduring vitality of the short form and the vigor of this ever-changing yet time-honored series.

This twenty-fifth volume reachs out beyond the South to one of the most acclaimed short story writers of our day. Guest editor Amy Hempel admits, “I’ve always had an affinity for writers from the South,” and in her choices, she’s identified the most inventive, heartbreaking, and chilling stories being written by Southerners all across the country.

From the famous (Rick Bass, Wendell Berry, Elizabeth Spencer, Wells Tower, Padgett Powell, Dorothy Allison, Brad Watson) to the finest new talents, Amy Hempel has selected twenty-five of the best, most arresting stories of the past year. The 2010 collection is proof of the enduring vitality of the short form and the vigor of this ever-changing yet time-honored series.

Release date: August 17, 2010

Publisher: Algonquin Books

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

New Stories from the South 2010

Amy Hempel

Today the Saints won the Super Bowl. So I was thinking of what New Orleans novelist Nancy Lemann once said about the South: “There’s a lot of human condition going around.” There is a lot of human condition in the twenty-five stories that make up this anthology, and the authors go at it in immensely powerful ways. The power of humor, power of horror.

As series editor Kathy Pories and I read the stories that were up for consideration, I felt we were aligned in what we were looking for. What I wanted was, as Gary Lutz put it, “whatever I could never expect to get from anybody else.” After making my selections, I looked up past years’ contributors and found that thirteen of the writers here have been featured in the series before, and eleven of the writers are in New Stories from the South for the first time.

In 1996, the Algonquin staff, in conjunction with McIntyre’s bookshop, threw a two-day party in Pittsboro, North Carolina, outside Chapel Hill, to celebrate Best of the South, a tenth-anniversary collection. I was the Yankee tagalong who took a train from New York City and justified her presence as a pal and fan of some of those being honored. The reading lists I have put together in nearly thirty years of teaching are top-heavy with writers from the South. Many of them were in Pittsboro that weekend. I remember asking Mary Hood what she was doing in the class she was teaching that year as writer-in-residence at Ole Miss. “Life lies,” she said. “What’s that?” I asked. “You know,” she said, “like, ‘I thought my prime would last.’” Rick Bass was there, and Mark Richard. Bob Shacochis and Patricia Lear.

Rick Bass is back this year, his seventh appearance in the series, although other members of my personal pantheon, including Rick Barthelme, Allan Gurganus, and the late Barry Hannah, are not here, because they did not publish stories in 2009.

There were stories I adored but could not include, because those stories had already appeared in books published last year. Yet I chose to include “Retreat” by Wells Tower, a story that had already come out in his widely praised debut collection, Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned. “Retreat” was first published in McSweeney’s in 2007; two years later it was published in McSweeney’s again; the magazine ran a small-print apologia by the author on the copyright page, and it is worth looking up for its honest account of what it is to be a writer who doesn’t feel a story is finished just because it has been published. I admire his attitude and what it says about revision. I have now read three different published versions of this story, and I felt the alterations from McSweeney’s to book to the second McSweeney’s incarnation were such that I could include it here. This anthology ends with “Retreat,” and it is a comic dazzler.

Much of what I read from the contemporary South has a soundtrack. I hear Little Walter and Jimmy Reed and Carla Thomas, Ruby Johnson and Son Thomas. The blues legend I heard perform at the Hoka, in Oxford, Mississippi, when I was taken there by the late Barry Hannah and Willie Morris and Larry Brown. This was in another century (!), and in case I got too swoony over the scene, one of our party pointed out that he was “playing for his electric bill,” said, “His wife shot him in the stomach last year.”

I hear recordings made in the field in Yazoo City by Bill Ferris, then director of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at Ole Miss. The album of these old bluesmen is titled Bothered All the Time. There are visuals that sometimes go with these stories: photographs by Maude Schuyler Clay in Mississippi, and her cousin William Eggleston up in Memphis, the photographs of sacred landscapes—churches and cemeteries in the Delta—by Tom Rankin.

Then why is a story set in Italy the first in this year’s Table of Contents? The author, Adam Atlas, was born and raised in Louisville, Kentucky; in “New Year’s Weekend on the Hand Surgery Ward, Old Pilgrims’ Hospital, Naples, Italy,” we learn that events in Kentucky propelled the narrator to flee not only his home but his homeland, and fetch up in Naples, teaching English. This is only the second story Adam Atlas has published, and it is a pleasure to get to spotlight such a strong new voice. There are other stories here that struck me as distinctly Southern in character, stance, or voice, though they take place somewhere else: Padgett Powell’s “Cry for Help from France,” Brad Watson’s “Visitation,” and Megan Mayhew-Bergman’s “The Cow that Milked Herself.”

In addition to the human condition on display here, these stories have singular voices and striking language, the two things sure to win me over. The choices I made can be further understood this way: I don’t have much interest in causality in fiction, but I do want to see accountability. Cleverness doesn’t interest me, but humor—the darker the better—does. Menace is more interesting to me than violence. Blame doesn’t persuade me, but a deep sense of “Life’s like that” feels true. I prefer the natural world to the supernatural. I want effects, not just events. I look for stories that do not hide from real feeling behind irony, that are both of-the-moment and timeless, and that look at questions of loyalty, of what we owe one another. I want to see hard-barked people in retreat from the sweetness of their souls, and the collision of illusion and reality. I want yearning, not nostalgia. I want my breath to catch at a last line. I want “Not the surprise. The amazed understanding,” as the poet Jack Gilbert put it. I want something that I didn’t know I wanted.

The people who are present in these stories include a child who robs the dead to help his parents (“The Ascent,” by Ron Rash); a true coward’s reaction to the phrase, “Go for it,” in Padgett Powell’s story; a kid who can’t wait to get where he’s going even if it’s not really any place he wants to go (Ben Stroud, “Eraser”); an Iraq War veteran whose good intentions back home backfire publicly (“Someone Ought to Tell Her There’s Nowhere to Go,” by Danielle Evans). There are men attracted to evil, and women repelled by goodness. There is a giant catfish that refuses to die even after being skinned for a feast; we hear of it from the boy entrusted to keep the fish “hosed down with a trickle of cool water, giving the fish life one silver gasp at a time” (Rick Bass, “Fish Story”). “The facts kept dodging us,” explains a woman in Elizabeth Spencer’s “Return Trip.”

Marjorie Kemper died last year before “Discovered America” was published in Southwest Review. I’m glad to have her story here for the voice that tells you in the first paragraph that while “People warned us we might hit bad weather” on a road trip across the country, “most of the heavy weather turned out to be inside the car . . .” In Kenneth Calhoun’s “Nightblooming,” a “shady neighborhood” means “it’s leafy, not ghetto,” and a young man hears the words of an old musician “driving into my head like pennies dropped from eight miles up.” It’s prisoners we hear from in Stephen Marion’s ribald story, “The Coldest Night of the Twentieth Century,” as they break into the women’s cell block; later they will be “running from everything that could be run from.” Flirtations with death revive a couple’s erotic life in Aaron Gwyn’s “Drive”: “. . . and right before the truck coming toward them began flashing its lights, she glanced up, and then over.” In Emily Quinlan’s “The Green Belt,” “It was hard to be a triplet,” observes the father of a set; always there were “two copies of yourself who were doing correctly what you had just done wrong.” In Bret Anthony Johnston’s “Caiman,” a father wanting to provide his son with a pet says, “On the drive home, I’d seen the man under the causeway and pulled over for a look. Our ice chest was still in the bed of the truck from when we’d gone floundering . . . And he had only one left . . .” A boy yearns for victimization as the surest route to celebrity (and uses “Tarantino” as a verb) in “Jason Who Will Be Famous,” by Dorothy Allison. A man calls his father for help removing a dead deer from the pond in his yard (“House-warming,” by Kevin Wilson), though this is not the most pressing problem the son’s family faces. “Somebody started burning houses within a year after they blew up the first mountain,” writes Ann Pancake in “Arsonists,” set in West Virginia coal country. A sixty-three-year-old man inherits a grand but dilapidated mansion on his great-grandfather’s property, and sets out to bring it back to its glory—“It had shamed him to long for the house, and now he owned it” (“Idols,” by Tim Gautreaux). Laura Lee Smith gives us the Okefenokee Swamp as safe haven for a young man who “knows its secrets” (“This Trembling Earth”). “The swamp is a national preserve, but that doesn’t mean much to those of us who have always lived here.” In Ashleigh Pedersen’s “Small and Heavy World,” a community “moved up into the trees when the neighborhood flooded that April,” the folks looking down at water “the color of peanut butter.” The last two lines of Brad Watson’s “Noon.”

There’s more. George Singleton’s “Columbarium” features a woman’s refrain, as recalled by her son: “For at least fifteen years she substituted ‘No,’ ‘Okay’ or ‘I’ll do it if I have to,’ with ‘I could have gone to the Rhode Island School of Design . . .” A veterinarian examines his pregnant wife with an ultrasound probe in his clinic, says, “I think we cleaned this after the Rottweiler” (“The Cow That Milked Herself”). In Wendell Berry’s “A Burden,” a friend of the elderly, drunken Uncle Peach recalls having seen him “drink all he could hold and then fill his mouth for later.”

So. Why was a Chicago-born writer who grew up in Colorado and California and has lived in New York City for the past many years asked to select the stories for this important anthology of short fiction from the South? I was too thrilled at the invitation to ask!

Though one’s sense of geography is keen, it’s hard to feel there is much that separates us after reading the stories collected here. And I don’t get tired of hearing one of the truest things I’ve ever heard about writing, about life—William Faulkner’s famous observation that “The past is not dead. It’s not even past.” My sense of connection to the South has something to do with—not just being haunted, but as Jack Gilbert wrote, being “haunted importantly.”

Nancy Lemann wrote that “a place is different when you love someone in it.”

And when you read someone from it.

(from Narrative Magazine)

Outside, the neighbors were firing a pistol and setting off firecrackers in honor of the coming New Year. I decided to make a lasagna so I began chopping onions and I cut off the end of my thumb.

In Italy the emergency number is different for police and ambulances. I couldn’t remember which emergency number was which so I called a pediatrician to whom I had been giving English lessons and she called the ambulance.

The dispatcher started calling me, she kept asking me which building was mine and I kept telling her which one it was. I eventually realized the ambulance guys didn’t want to walk up all the stairs to my apartment, so I called my neighbor, Norma, to ask her to go down and meet them, but I accidentally called my ex-girlfriend on the speed dial. I don’t know if I hung up before it started to ring. The fourth time the dispatcher called, she said the ambulance guys were waiting at the bottom of the stairs. We began to argue. I told her I understood that they wanted me to go down but I was in one room and my thumb was in the kitchen. I kept saying, my thumb is on the cutting board! My thumb is on the cutting board with the onions in the kitchen!

Shut up, the dispatcher told me, just shut up.

When the ambulance guys finally came, they were put out and winded. They asked me if I had a plastic bag for the piece of thumb and they watched with their arms folded while I stumbled around and found them a plastic bag.

In the emergency room, a doctor began cleaning the wound using a silver cauterizing pen to stop the bleeding. Two delinquents with tanning-salon tans and blood on their shirts wandered in and started to watch. Their skin around their eyes was white from the goggles they use in the tanning booths and they kept staring at me and the place where the end of my thumb used to be.

While she was talking to a colleague about changing her clothes, the doctor pressed down into the wound with the pen. It felt like lightning going into my hand. Another doctor from the university where I teach English arrived, a pediatric allergist. He came in and put his hands behind his back and watched silently. The doctor cleaning the wound suddenly got serious and told the delinquents to go away. After she finished, the doctor said to come back the next day when there would be a hand surgeon on duty who could examine me. Then she said that the piece of thumb was useless. She pointed to a yellow trash can and told me to throw it away so I went over and threw it away.

The hand surgeon on duty said they would need to operate, and that even though my surgery couldn’t be scheduled until New Year’s Eve, three days off, I should admit myself the following morning, since there would be an open bed: “A bed opens up and you stay in it until it’s your turn to be operated on, that’s the way it works around here.” On New Year’s Eve, he told me, the Hand Surgery Ward would fill up with the Neapolitan delinquents who buy boxes of contraband fireworks to celebrate.

“Dozens of them will blow off their hands at midnight,” he said.

When I checked into the hospital, there was a family in the room. Their boy, Giovanni, was there because of a large firecracker he’d found on the ground. He just picked it up and it exploded in his hand. His father was a little shorter than me, barrel-chested with thick hands, a strong, straight nose, balding with straight hair on the sides of his head. He was wearing a green plaid shirt and jeans, very neat and clean. Giovanni’s hand was wrapped in a gigantic bandage and there were no fingers poking out of it. He said his fore- and middle fingers were just bones underneath the bandages, they didn’t have any skin on them anymore. His thumb had been blown out of its socket, all the muscles shredded. His pinky and ring fingers were okay though. On Saturday, just me and Giovanni and his father were in the room (there were four blue linoleum beds in that room, and four blue linoleum chairs, and there was a blue linoleum table). Giovanni and I had to have the same pre-op exams, the blood work, EKG, anesthesiology exams, and so on, so we went to those together. When we saw the anesthesiologist, Giovanni went in first. I waited outside while the orderlies looked at his X-rays and shook their heads and said, “Mamma mia” and, “What a shame.”

After dinner, Norma came to visit and we all talked. Giovanni and his father were from Vico Equense, a small town on the Amalfi Coast, near Sorrento. Norma mentioned her dog, Pasquale, and the boy’s eyes lit up, he said they had seven dogs, five for the boar hunt and two for hunting birds. Norma said she didn’t know that they hunted wild boar on the Amalfi Coast, and then Giovanni explained how clever and conniving the boars were and how they had killed a number of their dogs by tricking them into falling off a certain cliff. Giovanni was fourteen. He was a country kid like so many I had known back in Kentucky, tall and skinny, with bright eyes always watching everyone and everything in the room. The father was a bricklayer and they had some land. Giovanni was his only son.

We smelled cigarette smoke in the room but didn’t know where it was coming from. Norma started to talk about how she didn’t like to eat meat and we made fun of her. She left and really there wasn’t much to say, but Giovanni offered me a little cake. I told him I didn’t need it, that he and his father might need a snack, but Giovanni threw it onto my bed with his good hand and told me to have it for breakfast. He said that breakfast in the hospital wasn’t very good. Every time the orderlies came around with our meals, they also had one for Giovanni’s father. He had to help everyone else in the room cut their meat before he could allow himself to eat.

An orderly came by at eight that evening and warned us to hide our wallets, our watches, our phones. On Saturday nights, delinquents hid inside the hospital and roamed the halls, sneaking into the rooms and stealing whatever they could find. “Saturday nights are sad in the hospital,” the orderly said, “real sad.” After the orderly left, Giovanni’s father lay down on one of the empty beds. Fireworks were going off outside. In the dark, waiting for the delinquents, we saw the flashes. We heard a boom. A flare went up and I saw Giovanni in silhouette. He was looking out the window.

“Firecrackers,” he said.

The next morning, at about six-thirty, they brought in a guy who was moaning. He had gotten his hand stuck in a machine that cut off three of his fingers. He was from a place called Cassino, which is about halfway between Rome and Naples. He didn’t say much that morning because he had been in surgery for seven hours while they sewed his fingers back on. He was awake the whole time during the surgery. His thumb was still black with oil from the machine. The man slept and cigarette smoke seeped into the room. Giovanni’s father cleaned his son’s head with a Wet-Nap. He made his way down to his good arm and then he started to weep. Giovanni looked at the ceiling and tried not to cry.

A couple of hours after the man from Cassino came, the orderlies wheeled in a delinquent from Secondigliano, the notorious slum outside Naples, the epicenter of the clan wars around here. He had been playing with some fireworks and one went off in his hand. As soon as they brought him in he wanted to know when lunch was going to be served. He was taller than me with a large head and chin. Maybe he was a bit retarded or maybe he was the typical idiot-delinquent—he had just lost the upper digits of his middle and ring fingers but he didn’t even seem to care. His bandages were bloody and he was with the two friends who had driven him to the hospital. Then his mother arrived. Secondigliano started yelling at her, “What are you doing here, what are you doing here?” His mother slapped him on the head and said, “What the fuck have you done? What the fuck have you gotten yourself into?”

“Ma,” he said, “when do they serve lunch around here? Get me some smokes, get me some water, get me some decent food.” His mobile phone kept ringing and ringing.

The surgeon walked in, the surgeon who would be operating on me and Giovanni and Secondigliano. The surgeon first went to Giovanni and looked at the X-rays. Giovanni’s mother and sister were there too. The surgeon was very curt with the family. When the father asked if they could save the boy’s fingers, the surgeon said, “Save? Save? Excuse me, is there something you didn’t understand? Did I not explain myself well enough?” And the father who spoke only dialect and not real Italian didn’t say anything else. The surgeon had combed-back white hair, wore spectacles, and was extremely tan, probably from skiing. Because I was American, the surgeon was more respectful to me, giving me the formal Lei, and treating me with something that could be called tolerance, like tolerating a toothache. When Secondigliano’s case was explained to him, the surgeon told Secondigliano that at least the boy had the excuse of being young, but at Secondigliano’s age there was no excuse for playing around with fireworks. “Doc,” Secondigliano said, “is it possible to have a smoke in here every once in a while?” The surgeon said no, no smoking was permitted inside the hospital. Finally, he looked at the hand of the man from Cassino. The surgeon who had been on duty had operated on him. One of the fingers didn’t look so good. It might have to come off. Again.

The surgeon told Giovanni to follow him to another room so he could see what was underneath the bandages. Secondigliano chimed in, asking what time they would serve dinner and the surgeon didn’t answer. He just turned around and walked out. Later, I was outside the room, sitting in the hallway. I heard the white-haired surgeon saying to Giovanni’s family, “What happened to your son is an utter disaster. Despite our best efforts, we may not—” and then I stopped listening.

Norma visited me again that evening. We sat out in the hall and she asked if I had called my psychologist. I told her no, she was out of town and anyway it wasn’t such a big deal. I said the only hard part had been watching Giovanni’s father begin to cry, and while I was speaking I suddenly choked up and couldn’t talk anymore so we just sat there not saying anything. Eventually, a man came out from behind a door. The man was visiting his mother. By this time, Giovanni and his father had come out into the hall too, probably just to get out of that hot, blue room for a second. The man looked at my thumb and asked, “Firecrackers?” I said that I had cut myself while chopping onions. “Ah, a moment of distraction,” he said. “You should have been more careful.” He was one of these bald, macho types almost feminine in the machismo, the fastidiousness of the pressed jeans, the dramatic gestures with the hands on the hips, and then the hands in the air, gesturing. Giovanni and his father were standing there near us, not really part of the circle of conversation, but not apart from it either. The man started speaking, pontificating, “Idiots, whoever hurts themselves playing with firecrackers. They deserve what they get. There isn’t a person more stupid than the person who plays with firecrackers.” He went on and on. “I tell my son here never to touch firecrackers. Would you ever pick up any firecrackers, son?” “No, Dad, never.” “That’s right, son. I brought my only boy, my only son here with me tonight not just to visit his grandmother but so he could see what happens to idiots who play with firecrackers.” The man’s son must have been nine or ten. He was short, plump, and really hairy. He had glasses and a clubfoot and a little mustache. Giovanni and his father were standing there looking desperate. The man turned to Giovanni and said, “And you? What about you? Firecrackers?”

“Firecrackers,” Giovanni said.

“Firecrackers,” the man said, and looked at the ceiling dramatically.

I couldn’t listen to the man anymore. But five minutes later I saw him touch Giovanni’s chin and tilt it up. “Took a little bit of it in the face, did you?” He looked at the cuts and scrapes on that smooth, porcelain cheek.

Earlier that day, the man’s “companion,” a black-haired girl with gray teeth, wandered into our room. She saw me, asked me what had happened. I told her I had cut off the end of my thumb. She said, “You cut off your thumb?” My thumb was wrapped in gauze but it was pretty obvious I hadn’t cut the wholething off. I told her no, just this part here, just the end, and I showed her on my good thumb about how much I had cut off. She looked at me with her empty eyes. “You cut the whole thing off?” she said.

Secondigliano walked around the Hand Surgery Ward as if he were on holiday, going out and smoking, horsing around. After visiting hours were over, some friends of his arrived, two more delinquents. One of them was dressed preppy in blue jeans, a blue button-down shirt, and a navy blue sweater. The other one had an extremely oval-shaped head, which was shaved, a tanning-booth tan, and a big overbite. He was wearing a backward baseball hat and athletic gear. They brought a girl into the room too, a bleached blonde, and Giovanni stared at her and I stared at her, and even if she was big, even if she was tawdry, even if everyone around here knows female delinquents are the worst delinquents of all, she still embarrassed us, she devastated us, us in our pajamas and bandages and everything we didn’t have underneath those bandages. All of them went out to the stairwell and smoked, and the man from Cassino with three fingers cut off woke up and began to talk. He had a big store in Cassino. He had land with thirteen thousand olive trees on it. In the afternoon, his family and his brothers and sisters had called him, they told him it was time to stop working, time for him to retire. He was fifty-seven but had been working since he was fifteen and his brothers and sisters had told him it was time to stop. “We’re all getting older,” his brother had told him on the phone. “At our age we can only get ourselves into trouble.” The man from Cassino said he didn’t care anything about the finger that might have to come off. “When all this is over,” he said, “I just want to be able to eat again with two hands.”

Secondigliano and the two delinquents came back without the girl. The two delinquents pulled up their chairs next to his bed and began talking, sometimes screaming, mobile phones ringing constantly. While Secondigliano was out of the room, Giovanni offered me another kind of cake. I told him I didn’t want it and he rolled his eyes and said “Madonna però,” and threw it on my bed. “We’ve got to eat,” he said, “we’ve got to eat a lot. After midnight we can’t eat anymore.” I ate the cake. Giovanni’s father said his back hurt. He had fallen thirty feet in September and broken nine ribs. One of the ribs had punctured a lung. He rested his head at the foot of Giovanni’s bed and tried to sleep a little bit. The man from Cassino said he should take a night off from watching over Giovanni. There was a long pause. “A night off?” Giovanni’s father said, looking at his boy, his voice cracking.

The two delinquents stayed in the room. Secondigliano kept saying he still heard the firecracker ringing in his ears, he kept making a whistling sound like a bomb falling. The delinquent with the shaved head began telling Secondigliano how much the operation was going to hurt. The man from Cassino said, “What do you know?” and the delinquent held up his own hand. It was missing two fingers.

“Seven years ago I was playing around with some firecrackers, see . . .” he said and then he began to laugh.

The delinquents stayed until past midnight. At a certain point, Secondigliano’s mother called and Secondigliano said, “I’m sleeping, call me tomorrow,” and the delinquents laughed. We wanted to sleep, but the way the delinquents positioned themselves around Secondigliano’s bed was the classic way of the organized criminals, even the ones who aren’t organized criminals—a delinquent is wounded and the others sit next to him, they protect him and show off their loyalty. We knew better than to say anything. We didn’t want to make things worse. The night before, a guard had passed by every so often, but that night no guard passed by. The delinquent with the shaved head began talking to Giovanni’s father. They went through the various prognoses. If they can save this finger, if there’s enough of that bone left. The delinquents went away. We all went to sleep. At three a.m., Secondigliano’s phone rang. He spoke loudly. We all woke up and we didn’t say anything. Two hours later it rang again.

The next morning, Giovanni was the first one to be operated on. Then they called Secondigliano, and fifteen minutes later they called me. I was in the waiting area outside the operating room when I heard Secondigliano scream. He screamed three or four times and then nothing. I saw a man in a white coat and a beard run out of the room. It was scary, really scary. Then it was my turn and they wheeled me into the operating room. As they wheeled me through the doors I saw Secondigliano on a gurney, asleep. It was the anesthetic that had made him scream. They hadn’t even touched him yet.

There were two surgeons. One was the white-haired surgeon from the day before. The other I’d never seen. They asked me where I worked. I said I gave English lessons at the medical school. They asked me why I didn’t go there for the surgery and I said that I lived five minutes away from their hospital and thirty minutes away from the medical school and, anyway, most of the doctors I knew were pediatricians. They said those were good reasons. They wondered aloud if I was there as a kind of “favored” case. I told them I hadn’t asked anyone for any favors. Then they began to discuss if I were a “signaled” patient, which is to say someone who is less than “favored” but better than “normal.” Finally one said to the other, “Anyway, he told us he worked at the university, so he signaled himself.” I told them that they had asked me where I worked and I had answered honestly. The chief surgeon, the one with the white hair, asked me who I worked for at the university. I told him. He asked me who the director of my department was. I told him. He asked me what my role was and I pretended not to hear him. I heard the clicking of whatever they were using to shave a layer of skin from my thumb. I felt them transferring the skin onto my wound. He said he wanted me to say hello to the director of my department on his behalf. He repeated his request. “Do you k

As series editor Kathy Pories and I read the stories that were up for consideration, I felt we were aligned in what we were looking for. What I wanted was, as Gary Lutz put it, “whatever I could never expect to get from anybody else.” After making my selections, I looked up past years’ contributors and found that thirteen of the writers here have been featured in the series before, and eleven of the writers are in New Stories from the South for the first time.

In 1996, the Algonquin staff, in conjunction with McIntyre’s bookshop, threw a two-day party in Pittsboro, North Carolina, outside Chapel Hill, to celebrate Best of the South, a tenth-anniversary collection. I was the Yankee tagalong who took a train from New York City and justified her presence as a pal and fan of some of those being honored. The reading lists I have put together in nearly thirty years of teaching are top-heavy with writers from the South. Many of them were in Pittsboro that weekend. I remember asking Mary Hood what she was doing in the class she was teaching that year as writer-in-residence at Ole Miss. “Life lies,” she said. “What’s that?” I asked. “You know,” she said, “like, ‘I thought my prime would last.’” Rick Bass was there, and Mark Richard. Bob Shacochis and Patricia Lear.

Rick Bass is back this year, his seventh appearance in the series, although other members of my personal pantheon, including Rick Barthelme, Allan Gurganus, and the late Barry Hannah, are not here, because they did not publish stories in 2009.

There were stories I adored but could not include, because those stories had already appeared in books published last year. Yet I chose to include “Retreat” by Wells Tower, a story that had already come out in his widely praised debut collection, Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned. “Retreat” was first published in McSweeney’s in 2007; two years later it was published in McSweeney’s again; the magazine ran a small-print apologia by the author on the copyright page, and it is worth looking up for its honest account of what it is to be a writer who doesn’t feel a story is finished just because it has been published. I admire his attitude and what it says about revision. I have now read three different published versions of this story, and I felt the alterations from McSweeney’s to book to the second McSweeney’s incarnation were such that I could include it here. This anthology ends with “Retreat,” and it is a comic dazzler.

Much of what I read from the contemporary South has a soundtrack. I hear Little Walter and Jimmy Reed and Carla Thomas, Ruby Johnson and Son Thomas. The blues legend I heard perform at the Hoka, in Oxford, Mississippi, when I was taken there by the late Barry Hannah and Willie Morris and Larry Brown. This was in another century (!), and in case I got too swoony over the scene, one of our party pointed out that he was “playing for his electric bill,” said, “His wife shot him in the stomach last year.”

I hear recordings made in the field in Yazoo City by Bill Ferris, then director of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at Ole Miss. The album of these old bluesmen is titled Bothered All the Time. There are visuals that sometimes go with these stories: photographs by Maude Schuyler Clay in Mississippi, and her cousin William Eggleston up in Memphis, the photographs of sacred landscapes—churches and cemeteries in the Delta—by Tom Rankin.

Then why is a story set in Italy the first in this year’s Table of Contents? The author, Adam Atlas, was born and raised in Louisville, Kentucky; in “New Year’s Weekend on the Hand Surgery Ward, Old Pilgrims’ Hospital, Naples, Italy,” we learn that events in Kentucky propelled the narrator to flee not only his home but his homeland, and fetch up in Naples, teaching English. This is only the second story Adam Atlas has published, and it is a pleasure to get to spotlight such a strong new voice. There are other stories here that struck me as distinctly Southern in character, stance, or voice, though they take place somewhere else: Padgett Powell’s “Cry for Help from France,” Brad Watson’s “Visitation,” and Megan Mayhew-Bergman’s “The Cow that Milked Herself.”

In addition to the human condition on display here, these stories have singular voices and striking language, the two things sure to win me over. The choices I made can be further understood this way: I don’t have much interest in causality in fiction, but I do want to see accountability. Cleverness doesn’t interest me, but humor—the darker the better—does. Menace is more interesting to me than violence. Blame doesn’t persuade me, but a deep sense of “Life’s like that” feels true. I prefer the natural world to the supernatural. I want effects, not just events. I look for stories that do not hide from real feeling behind irony, that are both of-the-moment and timeless, and that look at questions of loyalty, of what we owe one another. I want to see hard-barked people in retreat from the sweetness of their souls, and the collision of illusion and reality. I want yearning, not nostalgia. I want my breath to catch at a last line. I want “Not the surprise. The amazed understanding,” as the poet Jack Gilbert put it. I want something that I didn’t know I wanted.

The people who are present in these stories include a child who robs the dead to help his parents (“The Ascent,” by Ron Rash); a true coward’s reaction to the phrase, “Go for it,” in Padgett Powell’s story; a kid who can’t wait to get where he’s going even if it’s not really any place he wants to go (Ben Stroud, “Eraser”); an Iraq War veteran whose good intentions back home backfire publicly (“Someone Ought to Tell Her There’s Nowhere to Go,” by Danielle Evans). There are men attracted to evil, and women repelled by goodness. There is a giant catfish that refuses to die even after being skinned for a feast; we hear of it from the boy entrusted to keep the fish “hosed down with a trickle of cool water, giving the fish life one silver gasp at a time” (Rick Bass, “Fish Story”). “The facts kept dodging us,” explains a woman in Elizabeth Spencer’s “Return Trip.”

Marjorie Kemper died last year before “Discovered America” was published in Southwest Review. I’m glad to have her story here for the voice that tells you in the first paragraph that while “People warned us we might hit bad weather” on a road trip across the country, “most of the heavy weather turned out to be inside the car . . .” In Kenneth Calhoun’s “Nightblooming,” a “shady neighborhood” means “it’s leafy, not ghetto,” and a young man hears the words of an old musician “driving into my head like pennies dropped from eight miles up.” It’s prisoners we hear from in Stephen Marion’s ribald story, “The Coldest Night of the Twentieth Century,” as they break into the women’s cell block; later they will be “running from everything that could be run from.” Flirtations with death revive a couple’s erotic life in Aaron Gwyn’s “Drive”: “. . . and right before the truck coming toward them began flashing its lights, she glanced up, and then over.” In Emily Quinlan’s “The Green Belt,” “It was hard to be a triplet,” observes the father of a set; always there were “two copies of yourself who were doing correctly what you had just done wrong.” In Bret Anthony Johnston’s “Caiman,” a father wanting to provide his son with a pet says, “On the drive home, I’d seen the man under the causeway and pulled over for a look. Our ice chest was still in the bed of the truck from when we’d gone floundering . . . And he had only one left . . .” A boy yearns for victimization as the surest route to celebrity (and uses “Tarantino” as a verb) in “Jason Who Will Be Famous,” by Dorothy Allison. A man calls his father for help removing a dead deer from the pond in his yard (“House-warming,” by Kevin Wilson), though this is not the most pressing problem the son’s family faces. “Somebody started burning houses within a year after they blew up the first mountain,” writes Ann Pancake in “Arsonists,” set in West Virginia coal country. A sixty-three-year-old man inherits a grand but dilapidated mansion on his great-grandfather’s property, and sets out to bring it back to its glory—“It had shamed him to long for the house, and now he owned it” (“Idols,” by Tim Gautreaux). Laura Lee Smith gives us the Okefenokee Swamp as safe haven for a young man who “knows its secrets” (“This Trembling Earth”). “The swamp is a national preserve, but that doesn’t mean much to those of us who have always lived here.” In Ashleigh Pedersen’s “Small and Heavy World,” a community “moved up into the trees when the neighborhood flooded that April,” the folks looking down at water “the color of peanut butter.” The last two lines of Brad Watson’s “Noon.”

There’s more. George Singleton’s “Columbarium” features a woman’s refrain, as recalled by her son: “For at least fifteen years she substituted ‘No,’ ‘Okay’ or ‘I’ll do it if I have to,’ with ‘I could have gone to the Rhode Island School of Design . . .” A veterinarian examines his pregnant wife with an ultrasound probe in his clinic, says, “I think we cleaned this after the Rottweiler” (“The Cow That Milked Herself”). In Wendell Berry’s “A Burden,” a friend of the elderly, drunken Uncle Peach recalls having seen him “drink all he could hold and then fill his mouth for later.”

So. Why was a Chicago-born writer who grew up in Colorado and California and has lived in New York City for the past many years asked to select the stories for this important anthology of short fiction from the South? I was too thrilled at the invitation to ask!

Though one’s sense of geography is keen, it’s hard to feel there is much that separates us after reading the stories collected here. And I don’t get tired of hearing one of the truest things I’ve ever heard about writing, about life—William Faulkner’s famous observation that “The past is not dead. It’s not even past.” My sense of connection to the South has something to do with—not just being haunted, but as Jack Gilbert wrote, being “haunted importantly.”

Nancy Lemann wrote that “a place is different when you love someone in it.”

And when you read someone from it.

(from Narrative Magazine)

Outside, the neighbors were firing a pistol and setting off firecrackers in honor of the coming New Year. I decided to make a lasagna so I began chopping onions and I cut off the end of my thumb.

In Italy the emergency number is different for police and ambulances. I couldn’t remember which emergency number was which so I called a pediatrician to whom I had been giving English lessons and she called the ambulance.

The dispatcher started calling me, she kept asking me which building was mine and I kept telling her which one it was. I eventually realized the ambulance guys didn’t want to walk up all the stairs to my apartment, so I called my neighbor, Norma, to ask her to go down and meet them, but I accidentally called my ex-girlfriend on the speed dial. I don’t know if I hung up before it started to ring. The fourth time the dispatcher called, she said the ambulance guys were waiting at the bottom of the stairs. We began to argue. I told her I understood that they wanted me to go down but I was in one room and my thumb was in the kitchen. I kept saying, my thumb is on the cutting board! My thumb is on the cutting board with the onions in the kitchen!

Shut up, the dispatcher told me, just shut up.

When the ambulance guys finally came, they were put out and winded. They asked me if I had a plastic bag for the piece of thumb and they watched with their arms folded while I stumbled around and found them a plastic bag.

In the emergency room, a doctor began cleaning the wound using a silver cauterizing pen to stop the bleeding. Two delinquents with tanning-salon tans and blood on their shirts wandered in and started to watch. Their skin around their eyes was white from the goggles they use in the tanning booths and they kept staring at me and the place where the end of my thumb used to be.

While she was talking to a colleague about changing her clothes, the doctor pressed down into the wound with the pen. It felt like lightning going into my hand. Another doctor from the university where I teach English arrived, a pediatric allergist. He came in and put his hands behind his back and watched silently. The doctor cleaning the wound suddenly got serious and told the delinquents to go away. After she finished, the doctor said to come back the next day when there would be a hand surgeon on duty who could examine me. Then she said that the piece of thumb was useless. She pointed to a yellow trash can and told me to throw it away so I went over and threw it away.

The hand surgeon on duty said they would need to operate, and that even though my surgery couldn’t be scheduled until New Year’s Eve, three days off, I should admit myself the following morning, since there would be an open bed: “A bed opens up and you stay in it until it’s your turn to be operated on, that’s the way it works around here.” On New Year’s Eve, he told me, the Hand Surgery Ward would fill up with the Neapolitan delinquents who buy boxes of contraband fireworks to celebrate.

“Dozens of them will blow off their hands at midnight,” he said.

When I checked into the hospital, there was a family in the room. Their boy, Giovanni, was there because of a large firecracker he’d found on the ground. He just picked it up and it exploded in his hand. His father was a little shorter than me, barrel-chested with thick hands, a strong, straight nose, balding with straight hair on the sides of his head. He was wearing a green plaid shirt and jeans, very neat and clean. Giovanni’s hand was wrapped in a gigantic bandage and there were no fingers poking out of it. He said his fore- and middle fingers were just bones underneath the bandages, they didn’t have any skin on them anymore. His thumb had been blown out of its socket, all the muscles shredded. His pinky and ring fingers were okay though. On Saturday, just me and Giovanni and his father were in the room (there were four blue linoleum beds in that room, and four blue linoleum chairs, and there was a blue linoleum table). Giovanni and I had to have the same pre-op exams, the blood work, EKG, anesthesiology exams, and so on, so we went to those together. When we saw the anesthesiologist, Giovanni went in first. I waited outside while the orderlies looked at his X-rays and shook their heads and said, “Mamma mia” and, “What a shame.”

After dinner, Norma came to visit and we all talked. Giovanni and his father were from Vico Equense, a small town on the Amalfi Coast, near Sorrento. Norma mentioned her dog, Pasquale, and the boy’s eyes lit up, he said they had seven dogs, five for the boar hunt and two for hunting birds. Norma said she didn’t know that they hunted wild boar on the Amalfi Coast, and then Giovanni explained how clever and conniving the boars were and how they had killed a number of their dogs by tricking them into falling off a certain cliff. Giovanni was fourteen. He was a country kid like so many I had known back in Kentucky, tall and skinny, with bright eyes always watching everyone and everything in the room. The father was a bricklayer and they had some land. Giovanni was his only son.

We smelled cigarette smoke in the room but didn’t know where it was coming from. Norma started to talk about how she didn’t like to eat meat and we made fun of her. She left and really there wasn’t much to say, but Giovanni offered me a little cake. I told him I didn’t need it, that he and his father might need a snack, but Giovanni threw it onto my bed with his good hand and told me to have it for breakfast. He said that breakfast in the hospital wasn’t very good. Every time the orderlies came around with our meals, they also had one for Giovanni’s father. He had to help everyone else in the room cut their meat before he could allow himself to eat.

An orderly came by at eight that evening and warned us to hide our wallets, our watches, our phones. On Saturday nights, delinquents hid inside the hospital and roamed the halls, sneaking into the rooms and stealing whatever they could find. “Saturday nights are sad in the hospital,” the orderly said, “real sad.” After the orderly left, Giovanni’s father lay down on one of the empty beds. Fireworks were going off outside. In the dark, waiting for the delinquents, we saw the flashes. We heard a boom. A flare went up and I saw Giovanni in silhouette. He was looking out the window.

“Firecrackers,” he said.

The next morning, at about six-thirty, they brought in a guy who was moaning. He had gotten his hand stuck in a machine that cut off three of his fingers. He was from a place called Cassino, which is about halfway between Rome and Naples. He didn’t say much that morning because he had been in surgery for seven hours while they sewed his fingers back on. He was awake the whole time during the surgery. His thumb was still black with oil from the machine. The man slept and cigarette smoke seeped into the room. Giovanni’s father cleaned his son’s head with a Wet-Nap. He made his way down to his good arm and then he started to weep. Giovanni looked at the ceiling and tried not to cry.

A couple of hours after the man from Cassino came, the orderlies wheeled in a delinquent from Secondigliano, the notorious slum outside Naples, the epicenter of the clan wars around here. He had been playing with some fireworks and one went off in his hand. As soon as they brought him in he wanted to know when lunch was going to be served. He was taller than me with a large head and chin. Maybe he was a bit retarded or maybe he was the typical idiot-delinquent—he had just lost the upper digits of his middle and ring fingers but he didn’t even seem to care. His bandages were bloody and he was with the two friends who had driven him to the hospital. Then his mother arrived. Secondigliano started yelling at her, “What are you doing here, what are you doing here?” His mother slapped him on the head and said, “What the fuck have you done? What the fuck have you gotten yourself into?”

“Ma,” he said, “when do they serve lunch around here? Get me some smokes, get me some water, get me some decent food.” His mobile phone kept ringing and ringing.

The surgeon walked in, the surgeon who would be operating on me and Giovanni and Secondigliano. The surgeon first went to Giovanni and looked at the X-rays. Giovanni’s mother and sister were there too. The surgeon was very curt with the family. When the father asked if they could save the boy’s fingers, the surgeon said, “Save? Save? Excuse me, is there something you didn’t understand? Did I not explain myself well enough?” And the father who spoke only dialect and not real Italian didn’t say anything else. The surgeon had combed-back white hair, wore spectacles, and was extremely tan, probably from skiing. Because I was American, the surgeon was more respectful to me, giving me the formal Lei, and treating me with something that could be called tolerance, like tolerating a toothache. When Secondigliano’s case was explained to him, the surgeon told Secondigliano that at least the boy had the excuse of being young, but at Secondigliano’s age there was no excuse for playing around with fireworks. “Doc,” Secondigliano said, “is it possible to have a smoke in here every once in a while?” The surgeon said no, no smoking was permitted inside the hospital. Finally, he looked at the hand of the man from Cassino. The surgeon who had been on duty had operated on him. One of the fingers didn’t look so good. It might have to come off. Again.

The surgeon told Giovanni to follow him to another room so he could see what was underneath the bandages. Secondigliano chimed in, asking what time they would serve dinner and the surgeon didn’t answer. He just turned around and walked out. Later, I was outside the room, sitting in the hallway. I heard the white-haired surgeon saying to Giovanni’s family, “What happened to your son is an utter disaster. Despite our best efforts, we may not—” and then I stopped listening.

Norma visited me again that evening. We sat out in the hall and she asked if I had called my psychologist. I told her no, she was out of town and anyway it wasn’t such a big deal. I said the only hard part had been watching Giovanni’s father begin to cry, and while I was speaking I suddenly choked up and couldn’t talk anymore so we just sat there not saying anything. Eventually, a man came out from behind a door. The man was visiting his mother. By this time, Giovanni and his father had come out into the hall too, probably just to get out of that hot, blue room for a second. The man looked at my thumb and asked, “Firecrackers?” I said that I had cut myself while chopping onions. “Ah, a moment of distraction,” he said. “You should have been more careful.” He was one of these bald, macho types almost feminine in the machismo, the fastidiousness of the pressed jeans, the dramatic gestures with the hands on the hips, and then the hands in the air, gesturing. Giovanni and his father were standing there near us, not really part of the circle of conversation, but not apart from it either. The man started speaking, pontificating, “Idiots, whoever hurts themselves playing with firecrackers. They deserve what they get. There isn’t a person more stupid than the person who plays with firecrackers.” He went on and on. “I tell my son here never to touch firecrackers. Would you ever pick up any firecrackers, son?” “No, Dad, never.” “That’s right, son. I brought my only boy, my only son here with me tonight not just to visit his grandmother but so he could see what happens to idiots who play with firecrackers.” The man’s son must have been nine or ten. He was short, plump, and really hairy. He had glasses and a clubfoot and a little mustache. Giovanni and his father were standing there looking desperate. The man turned to Giovanni and said, “And you? What about you? Firecrackers?”

“Firecrackers,” Giovanni said.

“Firecrackers,” the man said, and looked at the ceiling dramatically.

I couldn’t listen to the man anymore. But five minutes later I saw him touch Giovanni’s chin and tilt it up. “Took a little bit of it in the face, did you?” He looked at the cuts and scrapes on that smooth, porcelain cheek.

Earlier that day, the man’s “companion,” a black-haired girl with gray teeth, wandered into our room. She saw me, asked me what had happened. I told her I had cut off the end of my thumb. She said, “You cut off your thumb?” My thumb was wrapped in gauze but it was pretty obvious I hadn’t cut the wholething off. I told her no, just this part here, just the end, and I showed her on my good thumb about how much I had cut off. She looked at me with her empty eyes. “You cut the whole thing off?” she said.

Secondigliano walked around the Hand Surgery Ward as if he were on holiday, going out and smoking, horsing around. After visiting hours were over, some friends of his arrived, two more delinquents. One of them was dressed preppy in blue jeans, a blue button-down shirt, and a navy blue sweater. The other one had an extremely oval-shaped head, which was shaved, a tanning-booth tan, and a big overbite. He was wearing a backward baseball hat and athletic gear. They brought a girl into the room too, a bleached blonde, and Giovanni stared at her and I stared at her, and even if she was big, even if she was tawdry, even if everyone around here knows female delinquents are the worst delinquents of all, she still embarrassed us, she devastated us, us in our pajamas and bandages and everything we didn’t have underneath those bandages. All of them went out to the stairwell and smoked, and the man from Cassino with three fingers cut off woke up and began to talk. He had a big store in Cassino. He had land with thirteen thousand olive trees on it. In the afternoon, his family and his brothers and sisters had called him, they told him it was time to stop working, time for him to retire. He was fifty-seven but had been working since he was fifteen and his brothers and sisters had told him it was time to stop. “We’re all getting older,” his brother had told him on the phone. “At our age we can only get ourselves into trouble.” The man from Cassino said he didn’t care anything about the finger that might have to come off. “When all this is over,” he said, “I just want to be able to eat again with two hands.”

Secondigliano and the two delinquents came back without the girl. The two delinquents pulled up their chairs next to his bed and began talking, sometimes screaming, mobile phones ringing constantly. While Secondigliano was out of the room, Giovanni offered me another kind of cake. I told him I didn’t want it and he rolled his eyes and said “Madonna però,” and threw it on my bed. “We’ve got to eat,” he said, “we’ve got to eat a lot. After midnight we can’t eat anymore.” I ate the cake. Giovanni’s father said his back hurt. He had fallen thirty feet in September and broken nine ribs. One of the ribs had punctured a lung. He rested his head at the foot of Giovanni’s bed and tried to sleep a little bit. The man from Cassino said he should take a night off from watching over Giovanni. There was a long pause. “A night off?” Giovanni’s father said, looking at his boy, his voice cracking.

The two delinquents stayed in the room. Secondigliano kept saying he still heard the firecracker ringing in his ears, he kept making a whistling sound like a bomb falling. The delinquent with the shaved head began telling Secondigliano how much the operation was going to hurt. The man from Cassino said, “What do you know?” and the delinquent held up his own hand. It was missing two fingers.

“Seven years ago I was playing around with some firecrackers, see . . .” he said and then he began to laugh.

The delinquents stayed until past midnight. At a certain point, Secondigliano’s mother called and Secondigliano said, “I’m sleeping, call me tomorrow,” and the delinquents laughed. We wanted to sleep, but the way the delinquents positioned themselves around Secondigliano’s bed was the classic way of the organized criminals, even the ones who aren’t organized criminals—a delinquent is wounded and the others sit next to him, they protect him and show off their loyalty. We knew better than to say anything. We didn’t want to make things worse. The night before, a guard had passed by every so often, but that night no guard passed by. The delinquent with the shaved head began talking to Giovanni’s father. They went through the various prognoses. If they can save this finger, if there’s enough of that bone left. The delinquents went away. We all went to sleep. At three a.m., Secondigliano’s phone rang. He spoke loudly. We all woke up and we didn’t say anything. Two hours later it rang again.

The next morning, Giovanni was the first one to be operated on. Then they called Secondigliano, and fifteen minutes later they called me. I was in the waiting area outside the operating room when I heard Secondigliano scream. He screamed three or four times and then nothing. I saw a man in a white coat and a beard run out of the room. It was scary, really scary. Then it was my turn and they wheeled me into the operating room. As they wheeled me through the doors I saw Secondigliano on a gurney, asleep. It was the anesthetic that had made him scream. They hadn’t even touched him yet.

There were two surgeons. One was the white-haired surgeon from the day before. The other I’d never seen. They asked me where I worked. I said I gave English lessons at the medical school. They asked me why I didn’t go there for the surgery and I said that I lived five minutes away from their hospital and thirty minutes away from the medical school and, anyway, most of the doctors I knew were pediatricians. They said those were good reasons. They wondered aloud if I was there as a kind of “favored” case. I told them I hadn’t asked anyone for any favors. Then they began to discuss if I were a “signaled” patient, which is to say someone who is less than “favored” but better than “normal.” Finally one said to the other, “Anyway, he told us he worked at the university, so he signaled himself.” I told them that they had asked me where I worked and I had answered honestly. The chief surgeon, the one with the white hair, asked me who I worked for at the university. I told him. He asked me who the director of my department was. I told him. He asked me what my role was and I pretended not to hear him. I heard the clicking of whatever they were using to shave a layer of skin from my thumb. I felt them transferring the skin onto my wound. He said he wanted me to say hello to the director of my department on his behalf. He repeated his request. “Do you k

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

New Stories from the South 2010

Amy Hempel

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved