- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

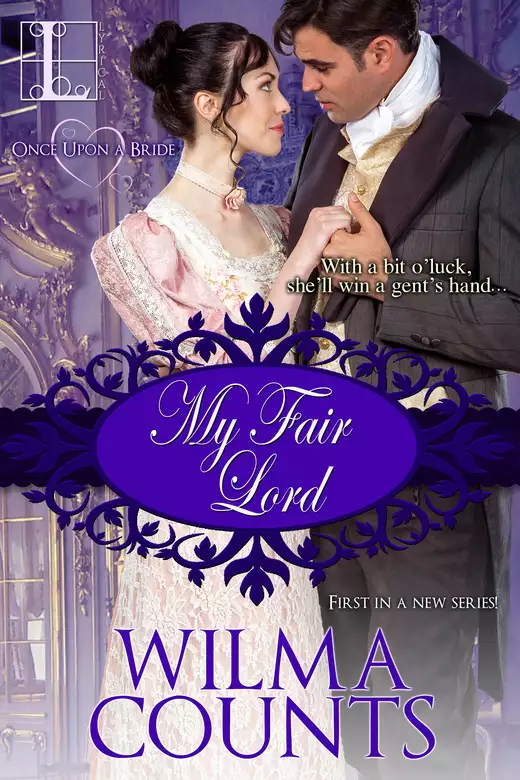

Synopsis

Well-bred, well-dressed, and well-read, Henrietta, Harriet, and Hero are best friends who have bonded over good books since their schooldays. Now these cultured ladies are ready to make their own happy endings—each in her own way . . . Lady Henrietta Parker, daughter of the Earl of Blakemoor, has turned down many a suitor for fear that the ton ’s bachelors are only interested in her wealth. But despite the warnings of her dearest friends, Harriet and Hero, she can’t resist the challenge rudely posed by her stepsister: transform an ordinary London dockworker into a society gentleman suitable for the “marriage mart.” Only after a handshake seals the deal does Retta fear she may have gone too far . . . When Jake Bolton is swept from the grime of the seaport into the elegance of Blakemoor House, he appears every inch the rough, cockney working man who is to undergo Retta’s training in etiquette, wardrobe, and elocution. But Jake himself is a master of deception—with much more at stake than a drawing room wager. But will his clandestine mission take second place to his irresistible tutor, her intriguing proposal . . . and true love?

Release date: October 17, 2017

Publisher: Lyrical Press

Print pages: 222

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

My Fair Lord

Wilma Counts

London

Late September, 1814

Henrietta Georgiana Parker, Lady Henrietta to members of the ton, that highest echelon of London society, was simply Retta to her intimate friends, to her father, and to her siblings—her younger half-brothers and half-sisters. Her father’s siblings, Uncle Alfred and Aunt Georgiana, also affectionately called her Retta. Her stepmother, Countess of Blakemoor, on the other hand, deplored the vulgarity of having one’s name shortened thus. Retta did not mind it at all.

One sunny day in early autumn, Retta was hosting visitors in the drawing room of her father’s elegant London town house.

One might wonder why the eldest daughter of the Earl of Blakemoor was hostess on this occasion, for everyone knew the countess would never tolerate a lesser being usurping her position—and a stepdaughter was certainly a lesser being.

The explanation: the earl and his countess were not in residence.

Only the children were, along with the earl’s brother, the aforementioned Uncle Alfred, and the countess’s rather aged and somewhat dotty but lovable Cousin Amabelle, whose presence was intended to lend propriety to the temporarily parentless household that included two single young women. Society would, of course, have considered the newly married Lady Lenninger as far too young to be an appropriate chaperon for her sisters.

To say that only the “children” were in residence was misleading. Lady Henrietta and her twin half-brothers, Gerald and Richard, had all reached the age of majority—and more—and the younger sisters, Rebecca and Melinda, were nineteen and eighteen. Rebecca had recently married a properly titled young man, Baron Lenninger, and Melinda had danced her way through her second season.

Retta was fonder of her twin brothers than of her sisters, perhaps because they were closer to her in age, there being less than three years between them. She often recalled with pleasure hours in the nursery reading to the little boys as soon as she had herself mastered that skill. Even then, she had sensed that Gerald, Lord Heaton, would grow up to be the more responsible and scholarly of the two, and that Richard would always be easily distracted by sport and any scheme offering adventure.

In their nursery days, she had earnestly tried to be as fond of the girls too, but found she shared very few of their interests. Besides, Rebecca and Melinda had, in those early days, spent much time in their mother’s company—a circle in which Retta rarely felt truly welcomed. Playing with dolls and dressing up to pretend to be ladies of fashion had never interested Retta, whom her stepmother often scolded for having her nose in a book or riding her pony far too fast. “You will never get a husband if you continue to behave in such an unladylike manner, Henrietta.”

The absent Earl of Blakemoor and his countess, along with many of the rest of London’s governing ministers and social elites, were traveling via Paris to Vienna, Austria, where the earl was to fulfill a minor role in the Congress of Vienna, set to open at the beginning of November. The countess, Retta knew, would try mightily to fulfill a self-declared role as one of the leaders of the sparkling social whirl intended to alleviate the tedium of the serious business of the Congress: dividing up the imperial spoils of the recently deposed Emperor of France.

Napoleon, of course, was not to be present in Vienna. After his defeat at the Battle of Nations at Leipzig, and his subsequent abdication, he had been consigned to the island of Elba where he presumably licked his wounds and regretted his folly. Retta was aware that not everyone shared that prevailing view of the former dictator’s current activities. Even as England had all that summer of 1814 engaged in giddy celebration of the emperor’s defeat, there were some—voices in the wilderness—warning that the intrepid Napoleon Bonaparte might have more up his sleeve than his heretofore powerful arm.

Her last casual guests, having stayed the obligatory quarter hour for a “morning” call, had departed, and Cousin Amabelle had excused herself for her customary afternoon nap, so Retta was enjoying a “comfortable coze” with her two best friends—the Honorable Harriet Mayfield and Miss Hero Whitby. The three of them had been thrown together at the age of fifteen in Miss Penelope Pringle’s Academy for Young Ladies of Quality. All three girls had been essentially motherless, though Retta did have a stepmother. Both Harriet and Retta had lost their mothers early on—Retta in infancy, and Harriet as a child of seven. Hero’s mother, whose love of classical myth showed in the girl’s name, had died when her daughter was in her teens, and, on arriving at the Academy, Hero was still feeling her loss keenly. Retta recalled that Hero’s father, a wealthy country squire and a doctor, had lovingly insisted that his daughter have the kind of education his wife, only child of a knight, would have wanted for her. Retta and Harriet, on the other hand, had found refuge at the Academy from their rather indifferent families.

Today, seated in the drawing room that the Countess of Blakemoor had recently redecorated in the popular Egyptian style with its vivid colors and a good deal of gold leaf and gold paint, the three friends looked exactly what they were: young women of fashion enjoying each other’s company. With her reddish brown hair and hazel eyes, Hero was dressed in her favorite soft green. Retta loved that Hero had long ago got over her embarrassment at her profusion of freckles. Harriet, in half-mourning for her sister and brother-in-law, wore a mauve day dress trimmed with black grosgrain ribbons that complemented her almost-black hair. Retta herself wore a dress of soft gray, simply because she liked the color. It was trimmed with touches of green velvet at the scooped neckline. The colors reflected the color of her eyes, which were essentially gray, but often showed a hint of green, depending on her clothing or mood. Her maid had dressed her brown hair in the popular “Greek” fashion: piled loosely on her head with soft tendrils before each ear.

As schoolgirls, the three had shared many interests. Each had taken supreme delight in escaping to faraway times and places through the medium of books. This fact alone would have earned them the label of “bluestockings” and relegated them to the sidelines in the society of their peers, but they also shared a passion for “doing good deeds,” though they might not have expressed it in precisely those terms. In fact, they had earned the sobriquet by which they were known in school for one of those causes. The “Ha’penny Hs” had campaigned—successfully, it turned out—for every girl in the school to give up at least a halfpenny of her allowance each week to provide relief to poor children in a nearby workhouse.

Now, a few years later, while each still held many of those interests and concerns, only Retta followed through on them with any degree of regularity, for the other two had busy lives in the country, Hero in assisting her father in his medical practice and Harriet in caring for her young nieces and nephews who had lost their parents in a horrible carriage accident. Harriet was determined that those children never feel as lonely and rejected as she once had.

“I do appreciate your helping with the Fairfax House charity during your visit,” Retta said, refreshing their cups from a covered teapot on a tray before her on a low table. “I hate that you are both returning to the country tomorrow. If only you could be in town more, just think what we might accomplish!”

“Fairfax House is a most worthy cause,” Hero said. “What the Fairfax sisters do for abused and abandoned women and children is simply amazing. But I must not desert Papa and his work any longer. That spell he suffered in the spring weakened him far more than he will admit.”

“I regret missing the next meeting of your literary group,” Harriet added. “I so enjoyed that last one. Imagine being able to talk with Maria Edgeworth herself after all these years of reading her novels! And I envy your having heard Lord Byron read his own work. What a treat that must have been.”

“You cannot stay for even a few days more?” Retta wheedled. “I shall be at sixes and sevens once you’ve left me on this desert island.”

Harriet exchanged a skeptical look with Hero and swept her hand in an inclusive gesture at their surroundings. “Such a desert island! A bit like an Arabian seraglio, is it not? At least I think that is the term for a Turkish harem.”

Retta shared an amused glance with them. “Yes. It is the right term—as you well know. The countess is quite taken with modern fashion.”

Retta rarely referred to her stepmother as anything but “the countess” and limited her direct addresses to the woman to “ma’am” or “my lady.” She respected her stepmother’s position in the household, but Retta had never quite forgiven the countess for persuading her husband to send his eldest daughter away to boarding school when the twins—as was wholly customary for boys—left home for school. The countess’s own daughters had been allowed to continue their education at home with a succession of governesses, art teachers, and music masters.

Of course, as she looked back on it, Retta realized that Miss Pringle’s Academy was the best thing to happen in her young life, but at the time she had felt lost and rejected and resentful, especially toward the countess who had engineered the change, but also toward her father. Although he had always been aloof with the “nursery set,” she had thought he cared about her enough to regret not having her near. She had felt betrayed. Just last week her feelings of resentment and abandonment had resurfaced.

“What is it, Retta?” asked Hero, always one to be in tune with the emotions of those around her. “We lost you there for a moment.”

Retta shrugged. “Oh, I was just thinking how wonderful it would be to be in Vienna where such important matters are to be decided—things that will affect all Europe for decades to come, and not just England and France. Wouldn’t you love to be there?”

“Of course,” Hero said. “Meeting all those important people would be an experience to remember in one’s dotage.”

Harriet leaned forward from her chair to set her cup down. “Hero, neither you nor I has the connections that would give us entrée to such exalted company.”

“But Retta does.”

Both her friends looked at her with eyebrows raised in question. “I wanted to go,” she said. “Oh, how I wanted to go. I thought I had convinced Papa to allow me to accompany him and the countess, but then he informed me that it was no place for a young woman. As though I were some green school girl!”

“Your stepmother talked him out of it.” Fiercely loyal, Hero was always quick to get to the heart of a matter. “I would wager she did not want an adult daughter to show her up. How very selfish.”

“Certainly unfair,” Harriet said.

Just then they heard laughter and chatter coming from the entrance below. It grew near as five young people climbed the stairs and burst into the drawing room enthusiastically discussing a curricle race they had witnessed. They exchanged greetings with Retta and her friends, whom they had all met previously, and returned to the excitement of the day.

“You should have seen it, Retta,” Richard said. “Bingham and Willitson neck and neck on Park Lane.”

“Good heavens!” Retta sat up straighter. “It is a wonder someone was not injured. Willitson was party to this?”

“Yes. Willitson,” Rebecca said with a sly look at her older sister as the newcomers arrayed themselves on chairs and settees. The door opened and Jeffries, the butler, entered carrying another, heavier tea tray. “I ordered more refreshments,” Rebecca added.

In the silence that ensued while the tea things were arranged and distributed, Retta surveyed the new arrivals. The girls were, of course, attired in the latest fashion of walking dresses with perky little bonnets to match: Rebecca in a vibrant blue to set off her silvery blond hair; Melinda, whose hair was a darker blond, in soft pink. Gerald, Viscount Heaton, always seemed aware of his position as heir to the earldom—having beat his brother to that status by a mere twelve minutes. Thus he was outfitted in a dark green coat, a gray silk waistcoat, and tan pantaloons; his neckcloth was tidy, but rather conservative—as was the cut of his light brown hair.

Baron Lenninger, Rebecca’s new husband, was dressed more flamboyantly in a blue coat, dark pantaloons, and a canary yellow waistcoat; his neckcloth was tied in an intricate pattern that must have taken his valet an age to achieve and his shirt points were so high Retta thought it must be difficult to turn his head. Lenninger obviously fancied himself a member of the dandy set.

Richard, the other man of the group, wore a tidy new scarlet uniform signifying his membership in His Majesty’s Army; he had his brother’s coloring—brown hair and brown eyes—but a very different disposition. Whereas Gerald was thoughtful and bookish, Richard was fun-loving, teasing, and restless. Often during the recent summer celebrations, Retta had heard Richard lament that “Boney” had been captured and incarcerated before many a deserving young officer such as himself had had a chance to win honor and glory on the field of battle.

When the butler had retreated, taking the earlier tray with him, Rebecca reached for a biscuit from a tiered serving dish. She nibbled at it daintily, then spoke again. “Is it true, Retta, that you refused Willitson’s offer? I simply could not believe it when his sister relayed that bit of news to me! He is handsome and titled. What more could a woman wish for, especially one who has been on the marriage mart for a goodly length of time?”

“It is not as though you must hold out for a fortune,” Melinda said.

Retta felt chagrin and annoyance spreading warmth across her cheeks. She glanced at the painting on the ceiling, a scene of cherubs frolicking in white clouds, and wished herself anywhere but right there, right then. Finally, she brought her gaze back to the group where she sensed sympathy from her friends and curiosity from her family members.

“Viscount Willitson’s sister has no cause to be airing her brother’s private business,” she said to Rebecca, hoping she would see the obvious parallel. She turned to Melinda, who sat next to her on a settee, and added, “Moreover, this is hardly the place to discuss financial affairs—mine or anyone else’s.”

“So it is true.” Rebecca ignored Retta’s less than subtle admonishment and made a show of examining her nails. “Well, I suppose that means that as an elder—spinster—sister, you really should have danced barefoot at my wedding.”

“Old wives’ tales notwithstanding, I believe my behavior that day was proper for any guest at an elegant ton wedding,” Retta said primly. As she returned the teapot to its place on the tray, she silently berated herself for allowing Rebecca and Melinda to annoy her so.

Gerald rose to stand next to the unlit fireplace and leaned his arm along the mantel. “So, Retta, now that Willitson’s sister has made the matter public fodder, would you care to share with us just why you did refuse the fellow?”

“May we just dismiss the subject with a simple statement that I did not think we would suit?”

He nodded. “As you wish, my dear.”

“But that is ridiculous!” Rebecca insisted. “Willitson is not some doddering old man seeking only to get an heir on a young wife before he departs this world. Willitson is not yet thirty. He is heir to an earl. And . . . he is known to be of the Prince Regent’s set.”

“Viscount Willitson has much to recommend him,” said Harriet who could always be counted on to lend a calming influence. “No doubt he will find a suitable bride in due time.”

Hero nodded her agreement and tried to divert the topic, if only slightly. “You know . . . in some circles, being of the Prince Regent’s set is not exactly high praise. Princess Caroline enjoys a remarkable degree of support in her efforts to force her husband to recognize her rightful place as the future queen of England. One can only feel sorry for the poor woman.”

Retta smiled her appreciation to her two friends who sat together on a gold and teal striped settee opposite the one she and Melinda occupied. However, she was not surprised when her sisters refused to drop a subject that would cause her discomfort.

“So why—or how—did you not ‘suit’? It seemed a perfect match to everyone. Did it not, my darling?” Rebecca cocked her silver blond head to send a simpering look up at her husband, who had risen to stand near her chair.

“That it did.” He patted her shoulder in a show of possession.

“Come on. Tell us, Retta. Do.” Melinda bent her darker blond head toward Retta in a conspiratorial manner and placed her hand on Retta’s arm. “I mean, after all, we are all practically family here.”

“Perhaps Retta is waiting for a knight in shining armor to storm in and sweep the princess off her feet,” Richard said with a saucy grin. He leaned back in his chair, crossed his legs, and laced his fingers across his chest.

Tactfully disengaging Melinda’s grip on her arm, Retta rose and began pacing the room. She released a brief sigh of resignation. “Nothing of the sort. I just happen to think there should be a certain meeting of the minds—shared interests, if you will—between a husband and wife. There should be more than just position and—and—whatever . . .” Her voice trailed off.

“I think Retta makes a very good point,” Harriet said, twisting to catch Retta’s gaze.

“So do I,” Hero said.

“Well, you two would, would you not?” Melinda’s tart tone bordered on rudeness, and she ignored Retta’s glare of reprimand. “My friend Rosemary said that when she went to Miss Pringle’s school just last year, the three of you were still famous as a trio of bluestockings who took no interest in society and were held in contempt by the girls who did. And just look at you—not one of you is married yet.”

Retta was embarrassed, more by her sister’s lack of manners than by the hurtful things she was saying. But rather than becoming overtly angry and making a scene, she merely said, “Perhaps one would do well not to listen to idle gossip.”

“Besides, those tales are somewhat exaggerated,” Harriet said. “We liked society well enough. Much of it, at any rate. And we loved music and dancing. Still do.”

Retta said in her best “reasonable” tone, “We liked books. We enjoyed learning. Still do. But in certain circles—”

Hero broke in. “After Retta was so audacious as to criticize members of the Four Horse Club as reckless fools whose racing on public highways was endangering the lives of others and was an abuse of horseflesh as well, Lady Frances Pennworthy gave us the cut direct. Her friends followed her lead. And—not that it matters a great deal—they are merely civil even now, years later. Her brother was one of the leaders of the Four Horse Club, you see.”

“The man is still a great horseman,” said Richard.

“After that—” Harriet threw up her hands. “Some members of the ton have long, if not wholly accurate, memories. And young girls can be very . . . well, adamant in the lines they draw. But you must not think for a moment that we had no other friends—that we cried ourselves to sleep every night out of pathetic loneliness.”

“Good heavens, no,” Hero said. “Remember the time Miss Pringle herself caught a number of us girls in Retta’s room having a gab session—”

“At two in the morning!” Harriet said.

Hero deepened her voice to sound stern. “‘You girls stop making so much noise and the rest of you go to your rooms this instant. Disgraceful. Utterly disgraceful.’ We have such memories, have we not?”

A murmur of nervous laughter followed as everyone seemed to find refuge in a teacup or a biscuit.

Then Rebecca, setting her cup and saucer on a table near her chair, again returned to the topic she had introduced. “But why, Retta? You have refused at least five offers since your debut. Whatever do you find so objectionable in England’s eligible men? The rest of us find them quite unexceptional. Some are quite adorable.” A coy glance at Lenninger accompanied this declaration. “You even refused the heir to the Marquis of Dorset, though he comes of excellent family and Mama thought him an eminently suitable match for you.”

Retta fought her rising temper. Why on earth was Rebecca pressing her so? “Yes. The countess made her view very clear. But she would not be the one to marry the Dorset heir, to sit across from him at the breakfast table every day, would she? And, yes, he is a very handsome man. A very pretty face. And I doubt there are even two worthwhile ideas floating around in his well-groomed head. Beyond his horses and hounds, that is.”

“Oh, I say—” protested Lenninger.

Too late Retta remembered that Lenninger had close ties to Dorset’s family. But by now she had become decidedly provoked. She refused to back down. Nor had she quit pacing; she paused in front of Rebecca.

“Look, Rebecca. Your views and your interests have always been very different from mine. I am sorry to say that I have found the marriage mart sadly lacking in possible partners. For me, that is. It is true that I had offers, but most were extended because I am—as Melinda unnecessarily pointed out, and thanks to my maternal grandmother—very rich. What is more, on my birthday in February, I shall have sole control of my affairs. Why would I turn all that over to some fortune hunter?”

Rebecca sniffed. “You cannot appear in company on the arm of your fortune.”

Richard gave a low whistle. “Egad, Retta, you underestimate yourself. And you don’t think much of men, do you?”

She took an empty chair near him and patted his arm. “I like you well enough, little brother. But I am heartily tired of being seen in terms of all those pounds sterling that I will have one day. I daresay one could take any worker off the London docks, dress him appropriately, teach him to talk without a cockney or country accent, limit his discussions to horses, hounds, and gaming, and you’d have a splendid specimen of your typical gentleman of the ton.”

“Oh, ho! Did you hear that?” Lenninger asked of no one in particular.

“You do not really mean that, do you, Retta?” Gerald cautioned from where he still stood near the fireplace.

She lifted her chin. “Yes, I think I do.”

“You may be right,” Harriet said, “but it is a hypothetical proposition that cannot be proved.”

“Why not?” Rebecca challenged. “I should like to see you put that theory to the test, oh sister mine.”

“As would I,” her husband echoed.

“Hear! Hear!” Richard said with a grin.

Melinda squealed and clasped her hands together. “A wager!”

“Oh, Retta,” Hero and Harriet said in unison, shaking their heads.

“This is preposterous,” Gerald said, straightening his stance. “All of you, do stop teasing Retta and discuss something else. Ladies do not make wagers.”

“Spoilsport.” Melinda directed a small moue at him.

“She was the one who said it could be done,” Rebecca said. “Let us see if she can follow through on such a bizarre claim.”

“What would be the terms of such an arrangement?” Richard asked.

They were all silent for a moment: Gerald, Harriet, and Hero apprehensive; the sisters, Lenninger, and Richard clearly considering the possible terms of such a wager. Retta mentally kicked herself for allowing the matter to get out of hand, but she would certainly not back down now!

“I have it,” Rebecca announced. “If Lady Henrietta fails to transform her dockworker into a gentleman by her birthday, she will forfeit to me that black mare Papa gave her on her last birthday.”

Retta gritted her teeth. All her life, it seemed, she had endured Rebecca’s envy and covetousness. The countess had once forced Henrietta to give up her favorite doll to the pouting Rebecca. “Rebecca is just a little girl and you—” Later, it had been a ball gown that Retta had bespoken with a modiste. Nothing would do but that Rebecca should have one exactly like it, though in a different color, thus making Retta’s gown less special. Retta remembered the vicious whispers. “Oh, look, another set of Blakemoor twins. Are they not just too sweet?” And now Rebecca wanted her precious Moonstar? No. It could not happen.

But she found herself snapping, “And if I win?”

Rebecca laughed. “I doubt you would want my first born son. No, really—how about my emerald necklace and earbobs? They are worth far more than a horse.”

“I cannot believe any of you are taking this idea seriously,. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...