- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

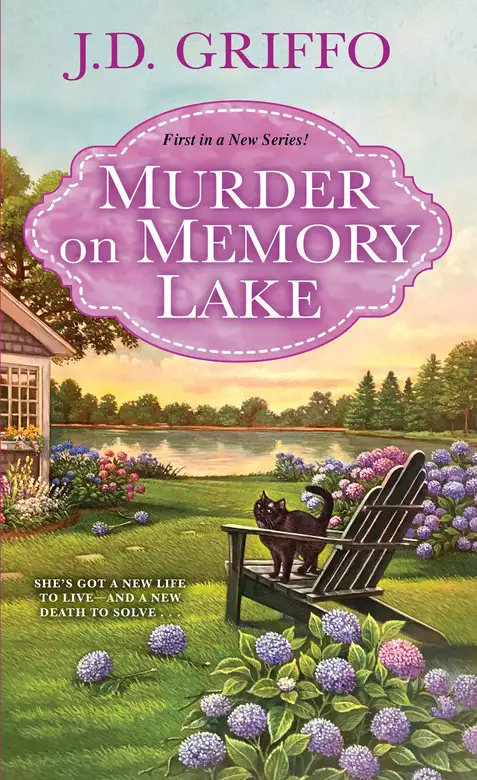

For Alberta Scaglione, her golden years are turning out much more differently than she expected—and much more deadly . . .

Alberta Scaglione's spinster aunt had some secrets—like the fortune she squirreled away and a secret lake house in Tranquility, New Jersey. More surprising: she's left it all to Alberta. Alberta, a widow, is no spring chicken and she's gotten used to disappointment. So having a beautiful view, surrounded by hydrangeas, honeysuckle, and her cat, Lola, sounds blissful after years of yelling and bickering and cooking countless lasagnas.

But Tranquility isn't as peaceful as it sounds. There's a body in the water—and it belongs to Alberta's childhood nemesis. Alberta suspects foul play and when Alberta's estranged granddaughter, an aspiring crime reporter, shows up, it only makes sense for them to team up and investigate . . .

Release date: July 31, 2018

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 334

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Murder on Memory Lake

J.D. Griffo

It’s a sweet, optimistic thought, one that is memorized by Italians of all ages, stored in the back of the brain, and forgotten until the difficult times arrive. Then when life becomes unbearable, when the rug, the flooring, and the earth itself, are ripped from underfoot, when the view below is all jagged rocks and open flames, it’s recited as if its words contained magic.

Being an old Italian lady, Alberta knew that old Italian saying by heart. She heard her mother say it defiantly while tears gathered in her eyes, she overheard her grandmother say it to even older relatives as they simultaneously made the sign of the cross, she even heard her father mumble it once when he thought he was alone. Throughout her lifetime she had uttered it herself, more often than she could remember, each time believing with a little less fervor that its miracle properties existed. Because, unfortunately, when disappointment is the constant companion of hope, it becomes hard to believe in the power of words, even those words that are handed down from generation to generation.

After one too many disappointments, disillusion replaced faith and Alberta had to accept the hard truth that the comfort those words were supposed to bring was never going to arrive. The gift of hope, the joy of a better tomorrow, was not going to be handed to her in a beautifully wrapped package with a shiny bow. Her mother, her grandmother, even her father, who knew everything about everything, were wrong, and that well-worn saying was nothing more than pio desiderio—wishful thinking. Or more bluntly, a waste of time.

“I’d rather believe in the power of a good lasagna,” Alberta would say, “than some pazzo string of words that mean nothing.”

This realization struck Alberta early on in her life, in her mid-twenties, when she was a wife and mother and the world around her should have been filled with joy and wonder, when the future should have invoked feelings of curiosity instead of apathy, and the past should have made her smile instead of question her choices. But even though it was a devastating turning point, Alberta was grateful for the strength to understand the truth. Had she ignored this knowledge and kept on repeating the words Finchè c’è vita c’è speranza, it would have been like reciting the rosary without believing in prayer. So instead of deceiving her soul, Alberta decided to live her life without having any expectations.

Knowing her change of heart would be met with disapproval and pity, she kept her plan of action to herself. And her silence served her well.

Day after day she toiled on in private, pushing forward, but not expecting to arrive at a place superior to the one from where she began. Surprisingly, most days were fine. Some were better than others, some were harder, just like the days experienced by everyone else around her, even those who clung to the old saying with desperate, greedy hands. The only difference was that she saw how the hopeful were constantly dejected when their lives never changed and was thankful that she didn’t allow blind faith to lay heavy on her chest like an invited albatross.

Most days she had even forgotten that she had chosen to live a life devoid of hope and carried on with the chores of the living as if it were business as usual. Moments arrived, memories faded, anniversaries flew by all on their own volition without Alberta’s permission or involvement. Sometimes she felt as if she were living someone else’s life and fulfilling someone else’s destiny, and on the rare occasions when she stopped to think about her own life’s possibilities, she felt powerless to change what she considered to be inevitable. So, when those thoughts came into her head, she rolled her eyes and did something practical, like try, for the umpteenth time, to perfect one of her grandmother’s recipes.

Then one day a few weeks before her sixty-fourth birthday, when Alberta was no longer a wife, but a widow, and long after her children needed a mother to survive, something quite unexpected happened—the gift of hope that decades earlier Alberta dismissed as nothing more than pio desiderio, as unhealthy and wasteful fantasy, finally arrived. Not on the wings of an angel, but the heels of a hearse.

At eighty-eight years old and as a nine-year resident of the Sisters of Mercy nursing home, Carmela’s death wasn’t unexpected, but it still caught Alberta by surprise because she thought her aunt should’ve died a long time ago and was surprised she had hung on for so long.

To say that Carmela was no longer engaged in life was an understatement. For the past five years she hadn’t spoken a word, nor had she been able to take care of her basic bodily functions. She was being held a prisoner on earth by her own stubbornness. She slept her days away or stared out the window at the world she was no longer a part of, and during each visit Alberta couldn’t understand why this woman clung on to a life she no longer was living.

“Just go already,” Alberta would whisper in Carmela’s ear when it was just the two of them in the room. “There is nothing left for you here, so just die for Crise sake.”

If anyone overheard Alberta they would have labeled her a cruel, evil woman, but quite the opposite was true. Alberta loved her Aunt Carmela and thought she was the most courageous woman she knew, who had lived a long, if not necessarily fulfilling, life and was now doing nothing more than taking up space. A cruel thought, perhaps, but a realistic one nonetheless.

When the shock of Aunt Carmela’s death wore off, Alberta hoped her words and the compassion behind them in some way helped her aunt decide it was time to stop fighting the inevitable. The only thing that shocked her more than hearing the news about her aunt’s death was receiving a call from Giancarlo Mastrantonio, Jr.

“Is this Alberta Ferrara Scaglione?”

The voice on the other end of the call sounded as if it belonged to someone who had a minor role in The Godfather, so Alberta was immediately suspicious. It could either be a long-lost relative or some duplicitous scam artist/telemarketer, and she didn’t know which was worse.

“Who’s asking?”

“This is Giancarlo Mastrantonio, Jr.”

The caller announced his name with such confidence, a proclamation of sorts, as if the mere mention of it should impress the listener, or at least instill a sense of recognition. It did neither.

“Who?” Alberta replied, not even trying to conceal her annoyance.

“Giancarlo Mastrantonio, Jr.,” he repeated. “Esquire.”

“Ah, Madon!” Alberta swore. “I am done talking with lawyers. My husband didn’t leave me any money, so go find yourself another patsy!”

A minute after she hung up the phone it rang again, and before she could tell Mr. Mastrantonio, Jr., exactly how she felt about lawyers and exactly what he could do with his slimy law degree, he said six words that changed her life forever.

“You’re inna your Aunt Carmela’s will.”

“What?”

“You know yourra Aunt Carmela . . . yourra father’s sister . . . she, uh, she passed away,” Giancarlo said delicately, as he wasn’t sure if he was conveying previously unheard news.

“Of course I know my aunt died!” Alberta shouted. “Who do you think picked out the dress she was buried in? It was her favorite, she wore it to my son Rocco’s wedding.”

“Oh, that was a very pretty dress,” Giancarlo replied. “The yellow was a . . . how do you say . . . a flattering color.”

“It made her look sallow!” she bellowed, then softened a bit when a memory returned. “But she loved the color and didn’t care less what anyone thought, so I figured it would be perfect.”

“I think you made a . . . bene choice, molto bene.”

“Yeah? Well, not everybody thought it was a good choice,” Alberta replied. “My sister, Helen, thought it made her look Asian, which I told her it absolutely did not, but you know my sister, she always has to be right even when she’s wrong. Wait a minute? What do you mean, I’m in Carmela’s will? My aunt didn’t have a will, she didn’t have anything.”

Then Giancarlo informed Alberta of how wrong she was about her aunt, and Alberta realized how very little she knew about the woman.

“She had how much money?!”

Alberta screamed so loudly that Giancarlo, who was wearing hearing aids, had to pull the phone away from his ear and let the high-pitched ringing noise subside before answering the question.

“I canna explain to you everything atta the reading of the will, but assa I said to you, it’s a substantial sum of money,” Giancarlo started. “Plussa, you have the house.”

“What house?!”

Again Giancarlo let the ringing subside, while on the other end of the line Alberta paced her kitchen as far as the phone cord would allow her to.

“The lake house,” Giancarlo said. “It’sa so pretty, you gonna love it.”

When Alberta hung up the phone, she thought she dreamed it all. She chalked it up to stress and didn’t believe a word Giancarlo had said until she found herself a few days later sitting in his office in a black leather club chair that looked like it was more expensive than every piece of furniture she ever bought in her life. Giancarlo did look like an extra from The Godfather, but thankfully one who was on the good side of Don Corleone. Although Giancarlo had sounded much older than Alberta on the phone, in person he looked about forty years old.

This one must’ve been born on the boat coming over, Alberta thought. Then she looked around the office and added, However he got to this country, he’s doing a lot better than me.

His office looked like one of those dens she saw in old movies. The walls were lined with bookshelves, stocked with rows of thick books that she couldn’t imagine one person having enough time to ever read. There was an abstract painting on the wall that looked like someone splattered black and red paint on a canvas and decided to call it art, and a rug that could have been designed by the same artist covered almost the entire office floor. Alberta didn’t like the decor but figured she’d have to budget for a year in order to afford the cheapest item in the room.

When Giancarlo spoke he sounded more like a longshoreman than a lawyer, and it took her a few minutes to focus on what he was telling her. But when she did, she realized that her Aunt Carmela was a stranger to her.

“So, if I understand what you’re telling me, and you’re not BS’ing me,” Alberta started. “My Aunt Carmela left me everything.”

“That is correct.”

Perplexed, Alberta replied, “Why would she leave everything to me?”

“I’ma so glad you asked that, Mrs. Scaglione,” Giancarlo said.

“Please call me Alberta.”

“Ofa course, Mrs. Alberta,” Giancarlo said, not quite understanding the request. He then picked up a manila envelope that was lying on his desk and opened it up with a letter opener that was so sharp Alberta thought it could double as a carving knife.

“These are your aunt’s own words that she wrote down justa before she went to live at Sisters of Mercy,” he explained. “I, Carmela Rosanna Ferrara, am the black sheep of my family not because I ever did anything wrong, but because I was never married and don’t have any children.”

“That’s very true,” Alberta interjected. “My father could never understand that, it broke his heart that she was a spinster. And every time he said that word he whispered it like it was a venereal disease or something French, like he was embarrassed to say the word out loud.”

“Ah yes, well,” Giancarlo said. “May I . . . a . . . go on?”

“Please, nobody’s stopping you.”

Clearing his throat, Giancarlo continued reading the letter. “But after I die and everybody learns the truth of what I have, I know all my relatives are going to come crawling out of the woodwork to try to get a piece of my estate. Over my dead body! That’s the last thing that I want to have happen. To prevent that, I am putting in writing that everything that I have goes to one person. Drumroll please.”

Giancarlo stopped reading and looked up at Alberta. “I don’t have-a any drums, sorry.”

“Not a worry,” Alberta replied. “The drums are rolling in my head.”

“I leave all my worldly possessions and all my money to my niece, Alberta.”

So that explains it. Sort of.

“But why? Why did she single me out?” Alberta asked. “Don’t get me wrong, I loved my Aunt Carmela, but we all did—well, maybe not everybody, my brother Anthony didn’t like her for some reason, something about her perfume smelling like Lysol—but nobody out-and-out hated her. Why would she just leave everything to me?”

At this question, Giancarlo’s eyes widened and he threw his hands up in the air. “I asked her the same-a question when she told me of her decision,” Giancarlo said. “I said to her, I said, Carmela, what makes thisa Alberta so speciale, I said.”

“Really?” Alberta asked, suddenly insulted by this stranger. “You asked her that?”

“Yes, because as her lawyer, that’sa my job,” he replied. “And all she woulda say is thata Alberta woulda understand why.”

Wrong. Alberta didn’t understand at all. But even though she didn’t understand her aunt’s motives, she did understand that she was now an incredibly wealthy woman.

“So, she left me all her money . . .”

“Almost three million dollars, plus her stock options.”

“Oh, yes, of course, the stock options, wouldn’t want to forget about those,” Alberta quipped. “And her lake house that nobody ever knew she had.”

“Oh, and there’sa one more thing,” Giancarlo said.

“There’s more?”

“You can’t give away any of the money for at least two years,” he instructed. “Carmela wanted that part in writing because she said your natural inclination woulda be to give the money away and not spend it on yourself.”

Alberta laughed out loud. “My aunt knew me like the back of her wrinkled hand, and I didn’t know a thing about her.”

“Your aunt, she was a very private person.”

“You’re telling me! I didn’t think she had a dime to her name!” Alberta cried. “Not for nothing but until she moved into the nursing home she lived with my father her whole life in an apartment in an old brownstone in Hoboken over a luncheonette, and she never told anybody she had a house of her own.”

“She didn’t want anyone to know,” Giancarlo explained. “It was her own private . . . ah, how do you say? Refuge.”

Alberta turned away from the lawyer because she had the sudden urge to cry and she didn’t think it was proper to cry in such a masculine setting. She wasn’t holding back tears because she thought it sad that her aunt kept such a huge secret or because she needed a home of her own to seek refuge and to escape her family, Alberta was holding back tears because she knew exactly how her aunt had felt.

“So where is this house?” Alberta asked.

“On Memory Lake.”

“Where the hell is that?”

“In a little town in New Jersey called . . . uh . . . Tranquility. Such a pretty name for a town.”

A very pretty name and, thankfully, to Alberta, a very memorable one. Located a little more than an hour northwest of Hoboken, which was where her ancestors emigrated to after leaving Sicily for a better life in America, Tranquility was the exact opposite of the Mile Square City. While Hoboken was a dirty, boisterous, crowded city, Tranquility was a clean, quiet, sparsely populated lakeside community. It was also where her entire family would spend two glorious weeks every summer.

“We used to vacation up there!” Alberta exclaimed. “The whole family and all our friends, two weeks every summer around the Fourth of July.”

“Carmela told me . . . she didn’t write this part down, but she told me . . . that it was her favorite place on earth.”

“And that’s the name of the lake?”

“Yes, Memory Lake,” Giancarlo confirmed. “You don’t remember that?”

“No,” Alberta answered. “We always called it the Big Lake because, well it’s huge. If your cabin was on the other side of the lake you might as well be living in New York.”

Alberta shook her head in disbelief. Interesting that she couldn’t remember the lake’s name was Memory Lake, and even more interesting that the memory of her Aunt Carmela would be forever changed thanks to this life-altering revelation. She was so lost in thought that she didn’t hear what Giancarlo said to her, but only saw him waving a set of keys in front of her eyes.

“It’sa your new home.”

And that’s exactly where Alberta was when her life changed yet again.

Sitting outside the gray-shingled Cape Cod with the bright yellow front door on the banks of Memory Lake in one of the faded black Adirondack chairs, which perfectly matched the faded black window shutters, holding a hot cup of coffee in her hands, her black cat, Lola, snuggled cozily in her lap, Alberta still found it hard to imagine her aunt sitting here by herself without the rest of her family milling about all around her. How odd it must have been to be here without every member of the Ferrara family, young and old, talking, laughing, eating, arguing, fighting, living in the same overcrowded space. Odd and yet oddly splendid. Yes, absolutely splendid. Alberta imagined that her aunt must have sat here looking at the same sun as it rose over the same crystal blue lake, the smell of hydrangeas and honeysuckle from the cluster of bushes that hugged the house adding a sweet fragrance to the air, and understood for the first time in a very long time what it felt like to be at peace.

That peace, unfortunately, was interrupted when she saw something floating on top of the lake.

With all the changes in her life recently, Alberta sometimes questioned her judgment; things she had taken for granted turned out to be wrong and things she never believed in turned out to be true. It took her almost a lifetime to understand that Finché c’è vita c’è speranza could be more than an empty saying. Where there is life, maybe . . . just maybe there could be hope.

That might be true for Alberta, but for the dead body floating on top of Memory Lake, all hope had definitely run out.

From the moment she was born, Gina Maldonado has had luck on her side. Most of it bad.

She wasn’t supposed to enter this world for another three weeks, so when her parents got the urge to play the one-armed bandits and watch some dice spin round the roulette wheel in Atlantic City they didn’t think twice about hopping into their used Ford Taurus to take the two-plus-hour drive in order to satisfy their craving. After all, in a few weeks, when the baby came, they wouldn’t have time to take spontaneous trips, and they could definitely use some extra money to pay for the endless baby things they were going to have to buy. Play the slots, buy a stroller, that was their mind-set when they gambled on a road trip. Gina’s grandmother just thought they were out of their minds.

“Ah, Madon!” Alberta shouted into the phone. “You two are crazy!”

“Why are we crazy?” Alberta’s daughter shouted right back. “Because we want to have some fun?”

“If you want to have fun, come with me to St. Joseph’s tonight for bingo,” Alberta suggested. “They’re having a progressive jackpot.”

“I don’t like to play bingo, Ma, you know that. I like to play the slots.”

“But a casino is no place for a pregnant woman!”

“Oh, for Crise sake, Ma, this isn’t 1950! It’s not like there’s gonna be a mob hit at Harrah’s on a Thursday afternoon.”

After a dramatic pause, Alberta replied, “You never know.”

Lisa Marie Scaglione Maldonado was used to arguing with her mother. For as long as she could remember it’s what they did. They argued about important things, inconsequential things. They argued on the phone, in private, in public, when they disagreed, even when they agreed. Lisa Marie didn’t know why or how it really started, but at some point, very early on in her life, she became aware that arguing and shouting was their only means of communication. It was something she grew used to, like the small, dark birthmark next to her right eyebrow. No matter how hard she tried she couldn’t fix it or make it look better. The birthmark always stood out, it was always going to be a flaw, and so she accepted it, just like she accepted her relationship with her mother. Normally it didn’t bother her, but ever since she had become pregnant the novelty had worn off. Maybe it was the hormones or maybe she had just grown weary from the noise, but talking to her mother had become tiresome.

As always, she should’ve listened to her husband, Tommy, who told her to call her mother when they got to Atlantic City. But knowing that her mother would worry if she couldn’t reach her all day long, she ignored his instructions and called before they left. Now she regretted her simple act of kindness.

Pressing the phone’s receiver into her forehead, Lisa Marie leaned her back against the kitchen wall, closed her eyes, and took a few deep breaths. In and out, in and out, and with each breath she prayed her relationship with the child that was squirming inside her belly wouldn’t be as combative as her relationship with her own mother. Or as loud.

Lowering her voice she restarted the conversation. “Tommy thought it would be nice to take advantage of his day off so he suggested . . .”

“He has the day off on a Thursday?” Alberta interrupted.

“Yes Ma, he has off on a Thursday,” Lisa Marie replied. “He’s scheduled to work the weekend so he has off today and tomorrow.”

“I wish he had a real job,” Alberta sighed. “It would be so much easier.”

Again, Lisa Marie pressed the phone receiver against her forehead, but this time there was no attempt to de-stress, no deep breathing, she gripped the phone so hard her fingers almost melded into the plastic and she had to resist the urge to slam the phone into her face. Would physical pain drown out her mother’s commentary?

“A stagehand at Radio City is a real job, Ma,” Lisa Marie replied, the volume of her voice no longer quite so low, “And a good one too. It’s just that he’s the low man on the totem pole so he doesn’t get to choose his hours, you know that.”

“No, of course,” Alberta said. “It’s just, you know . . .”

Lisa Marie couldn’t resist taking the bait. “No Ma, I don’t know.”

And Alberta couldn’t be happier reeling her daughter in. “Well, it’s always a new schedule every week with him, one week he’s off Thursday, the next week it’s Wednesday, and . . . well, with the baby coming, things are gonna get even more hectic and the one thing that makes a baby happy, Lisa Marie, the one thing . . . is a routine. That’s all I’m trying to say. A baby likes a routine.”

“I know that, Ma! Don’t you think I know that? And guess what? I’m gonna be the baby’s routine!”

“Well . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...