Paislee Shaw eyed the clock above the cooker as if Father Time were her mortal enemy. Half past eight already? She whirled to her son, just finishing breakfast at the round kitchen table, and caught him sneaking bits of sausage to the dog.

“Brody, if ye give Wallace one more bite it’ll be oatmeal tomorrow!”

Their black Scottish terrier lowered his ears even as he licked his whiskers and plopped down on the braided rag rug beneath Brody’s chair.

“Mum!”

Paislee wiped her hands on a cotton dishcloth and glared at her ten-year-old. “Tell me why I should take the time to make a special breakfast, then? Ye could have had a bowl of cereal and we’d both be happy.” And not running late. Her own fault, because she couldn’t leave the dishes until later like a sane single mother, short on time and long on responsibilities.

“Sairy,” Brody mumbled, dark auburn hair falling over a pale forehead. He was growing again, all teeth and gangly limbs as he propped bony elbows on the worn-smooth wooden surface.

If Paislee knew one thing, it was that her son detested oatmeal. She’d added brown sugar, sweet cream, orange currants—nothing swayed him. Most mornings they had Weetabix and blueberries, but since it was Monday and neither wanted their Sunday to be over, she’d made eggs, Lorne sausage, and toast. And the minute she wasn’t paying attention, the little imp fed Wallace on the sly.

Brody brought his empty plate to the sink, and she brushed off the crumbs, then dunked it in the soapy water. Modern appliances were what she dreamed about at night—there was nothing that sent her to a sweeter sleep than imagining a stainless-steel dishwasher and matching refrigerator. She rinsed the dish in the white double sink and put it in the dish rack on the laminated counter.

“Quick! Go brush your teeth and get your books for school. We have tae stop at the shop before I drop ye off.”

She didn’t wait to hear an argument as he stomped toward the downstairs bathroom but climbed the stairs to her bedroom for her cardigan. The third and fifth steps creaked, but such things were to be expected in a one-hundred-year-old house.

Two bedrooms upstairs, and a bathroom, for her and Brody. Gran’s suite of two rooms, mostly storage since Gran had died, a kitchen, living room, and covered back porch that led to a long and narrow garden for Wallace to chase squirrels.

The old sweet chestnut and wild cherry trees provided nuts and berries for birds and squirrels alike—sometimes leaving enough for her to make jam. She told herself that if things got too tight, she could clean the bottom bedroom and rent it out during the three summer months when tourism in Nairn was at its peak.

Grabbing the sweater off the back of her dressing room chair, Paislee dared a peek into the mirror. She groaned, glanced at her watch, and knew she didn’t have time for more than a slash of lip gloss. “Pale as moonlight,” her da used to tease; her face had nary a freckle to add color. Sky-blue eyes with auburn lashes and auburn hair that was so thin she was happiest with it up in a messy bun for the illusion of body. She applied the gloss as she ran down the stairs, pocketing the tube.

“Ready, Brody?” Her yarn order was supposed to arrive at nine on the dot and she’d promised to unlock the back door for Jerry, in case he arrived while she was dropping her son off at school. Even in heavy traffic, the two miles round trip should be no more than ten minutes. She hoped Isla, a very part-time rehire, could start right away and mornings wouldn’t be such a chore. They had an interview today at nine thirty.

Miracle of all miracles, her son had his jacket and runners on and was waiting by the door. “Have yer lunch?”

He smacked his forehead and ran to the kitchen for his cheese sandwich.

She expected a full morning of crafters at Cashmere Crush and had promised to help Mary Beth with the fancy soft pink hem around her blanket whose wool Paislee’d special ordered from Jerry. A christening gift for a wee baby girl. Aye, babies were adorable, but she was glad that her son was now able to brush his own hair, usually. Reaching for his head, she smoothed a defiant lock.

“I know, I know, ye cannae take one more thing.” Brody stuck out his lower lip and shrugged away from her touch.

She hated getting her own words tossed back at her. “Bein’ smart, are we?”

He grinned and she ushered him out the door and into the faded silver Nissan Juke. A carport protected her eight-year-old vehicle from the elements—usually rain, and lots of it, though compared to the rest of Scotland, Nairn had the driest weather with the most sunshine, something the Earl of Cawdor had been using in his slogans to repopulate the town and create prosperity for all.

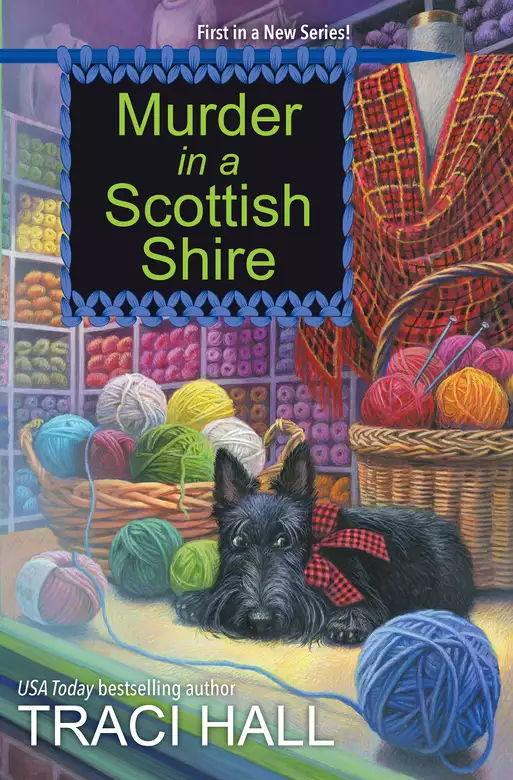

They drove the mile to Cashmere Crush, her specialty sweaters and yarn shop on Market Street—hers was on the end of a long row of single-story brick businesses the length of a block. Market Street was a main thoroughfare in front, and the road was separated from the shops by a narrow, uneven sidewalk.

Seaside scents and gulls’ caws rode the winds from the marina. In the back was a proper alley big enough for the delivery trucks, and across Market a row of two-story businesses in old stone. Behind the alley, she was back-to-back with a string of restaurants.

Her favorite restaurant across the alley was the Chinese one because she liked the fortune cookies. She and her granny used to make up funny fortunes that had them in stitches, and now she and Brody carried on the tradition—the sillier the better, like, the fortune you seek is another cookie.

“Brody, how do ye feel about chicken lo mein tonight for supper?”

“Aye! And orange beef?”

She nodded, her taste buds watering as she justified the expense with a full day ahead at the shop, which meant money in the register. Making a left on Hammond, she thought back to when she’d moved in with her granny, grateful for her insistence that Paislee could make it as a very young single parent—the belief that she owed nobody an explanation and had to hold her head high.

After her da had died, before her graduation from S6 at the age of seventeen—back when she’d still considered going to university—her mum had gone mental and married an American within the year just to get as far away from her grief as possible.

Paislee, grieving herself, had given up on ideas of college and moved in with her granny, who’d taught her to knit sweaters, sharing family patterns with pride. Somehow, ten years later, Paislee had managed to keep her and Brody fed—not smoked salmon or Aberdeen Angus, but they didn’t starve.

She’d been raised on stories of a big family, with aunts and uncles and cousins, but she’d grown up an only child and after her da’s death and her mum’s desertion—who fled the country, for mercy’s sake?—Granny had taken her in without judgment, showing unconditional love as Paislee was forced to navigate adulthood.

With a sniff of sorrow for her granny, Paislee parked her Juke behind Cashmere Crush to unlock the back door for Jerry’s delivery of local yarn, specifically, the light pink for Mary Beth’s blanket. “I’ll be right back,” she said to Brody, who ignored her and jumped out of the passenger side.

“Ye always say so, but . . .” Brody followed behind her, his sneakers scuffing the rough pavement. “Somethin’ happens. I can’t be late again. Mrs. Martin doesnae like it.”

“I’ll hurry.” After receiving Isla’s email last Sunday asking for her job back, Paislee had crunched numbers. Things were tight, but she could just manage fifteen hours a week and prayed that Isla would accept, because tourist season started at the end of April.

They entered through the back door of the shop, and Paislee flipped up the light switch just inside the storage area. The bulb above flickered, flared, and then fizzled. Did she even have a spare?

Brody giggled nervously in the dim interior. The store was a long rectangular shape less than eight hundred square feet and any natural morning light was blocked by the buildings across Market.

She carefully maneuvered around the crates, armchair, oval table, and small television she’d set up for Brody when he had to be at work with her to the switch for the overhead lights but then stopped, her gaze drawn to the shadowy entrance. Her heart hammered in her chest and she reached for Brody as she made out two silhouettes peering through the frosted glass of her front window.

“What?” he said, sliding free to walk around her to the register where she kept a jar of candy.

“Stop—they’ll see you.”

He froze like a squirrel targeted by Wallace in the garden. “We don’t have time tae open, Mum.”

“I know!” But she hated to turn away business. Too late—they’d been spotted. A light tap sounded against the frosted pane.

And now she didn’t feel comfortable leaving the back door open for Jerry, either.What if the strangers decided to find another way in?

Two of her ladies were due in this morning and they sometimes came early for tea and a blether. Could this be them? Not with those shoulders—not even Mary Beth at two hundred pounds.

Torn, Paislee slowly stepped to the door. Maybe if she explained that they didn’t open until half past nine, the two would come back . . . but she had a wild feeling in the pit of her belly that warned against a warm welcome.

Granny’s gift of premonitions hadn’t been handed down with the knack for knitting—this was something else. Fight or flight. She rubbed the goose bumps on her nape.

One shadow straightened and, moving to the door, pounded a heavy fist. The brass knob shook.

“Open up!” a man called.

“Mum.” Brody was suddenly at her side. “I don’t think that’s Jerry.”

“No. He’d use the back door.”

“Mibbe we should wait for him?”

Was she transferring her anxiety to her child? Get ahold of yourself, Paislee Shaw. With a heft of her chin, she smiled confidently. “I’m sure it’s nothing.”

Another firm knock sounded.

Taking a deep breath, she pulled the bolt and opened the door. A square-jawed gentleman with cool green eyes, shiny black shoes, and a Police Scotland rain jacket stood on the threshold next to an older man, seventy-ish, in a long tweed trench coat and with a dark green Tam-o’-shanter on his head.

The older man had dark glasses, a silver beard, and a brown suitcase.

Her breath caught. The last time a police officer had been at her door her da had died in a boating accident.

Brody stuck to her hip like a burr.

The officer smiled down at her son, then looked at her with mild reproof, as if reminding her of her manners. “May we come in?”

“Aye, of course.” She widened the door and then sucked at her teeth as she studied the older man.

It couldn’t be.

“I’m Detective Inspector Mack Zeffer,” the officer said. “I found this gentleman down at the park, sleeping on a bench. He says ye’re his only family.” He escorted the man in by the elbow.

“Grandpa Angus?” She’d seen him at Granny’s funeral five years ago. He lived with his son in Dairlee . . . or so she’d thought.

“You recognize him, lass?” The officer’s tone held more than a hint of relief.

“Aye.”

“Yer my grandpa?” Brody asked with a welcoming smile. Were they that starved for family that Brody had no reservations? The man hadn’t bothered to come around for years.

“Great-grandfather,” he corrected. The words were sharp and Brody lost his exuberance.

She pulled her son back to her side.

The clock tower chimed from the center of town, and she bowed her head as Brody pulled her cardigan. Nine on the dot. They were late. Again. “I have to go. . . .”

“All right, then, I’ll leave ye tae it,” the detective said as he headed for the door.

Grandpa Angus stayed put. “Wait—what do you mean?” Panic rose.

Detective Inspector Zeffer halted by a chest-high worktable stacked with pattern books and looked from the suitcase at her grandfather’s feet to Paislee. Zeffer’s russet hair, groomed into place, didn’t budge. “You are his only kin. He cannae go on sleeping in the park.”

Paislee shook her head. “I don’t understand.”

“I have nowhere else tae go.” Grandpa Shaw crossed his arms as if she were being purposefully dense.

A knock sounded on the back door and Jerry marched in. “Mornin’, lass. I’ve a wee bit of bad news—the pink yarn isnae ready yet.” Jerry McFadden joined them with a clomp of work boots and the scent of fresh spring air. He stopped at the counter separating the front of the shop from the supplies and nodded with chagrin at the police officer and her grandfather, then Brody. “Sairy—I thought ye’d be alone. Is everything all right?”

“Fine,” Paislee said automatically. “When will it be in?”

Jerry scrubbed his hand along his jaw. “Tomorrow, first thing. The dyeing machine broke, but it’s fixed now.”

She inhaled, clenched her fingers, and counted to five for patience. Mary Beth needed the pink yarn to finish the christening blanket—and to be billed. No yarn, no blanket, no money, no lo mein. Losing her temper was not an option. As a single mum, she had to set a proper example.

The front door swung open with a clatter, and in walked her landlord.

“Mr. Marcus?” The owner of the building was a man in his mid-fifties who’d rarely made an appearance in the last year due to ill health. She and the others in their brick row had worried aloud what might happen to their prized leases and Paislee was not the only business owner to say prayers of gratitude when Mr. Marcus had miraculously rallied, as evidenced by his brown comb-over and plump cheeks.

“How’re ye the day?” Glancing at her company, Mr. Marcus cleared his throat and handed her a letter with a green certification stamped on the front. “Ye can open it later, but it is time sensitive.”

Paislee frowned at the nervous gentleman. His skin wasn’t Scots pale but had an orange tint. A spray tan? Using her thumbnail, she lifted the adhesive and pulled out a sheet of paper on a solicitor’s letterhead.

She reeled backward as the black type swam before her eyes. Her grandfather steadied her elbow. “What is it, lass?”

“An eviction notice? But my lease is good for another year!” And she’d hoped to keep renewing until she could buy her own shop.

“Which is void on point of sale.” Mr. Marcus realized that Paislee was not taking the news well, and backed up, quickly wiping the smile from his face.

“How long?” Jerry asked in a threatening growl that made the detective look at him with warning.

“Thirty days,” Paislee managed. Her stomach clenched and the shop tilted. Cashmere Crush was her livelihood. She’d poured her life into it to create something for her and Brody to survive.

“Now, Ms. Shaw, I’m sure ye’ll find another place tae lease.” Mr. Marcus took a step toward the door.

Her temper flared at the tone of his condescending words. She forced herself to sound calm. “Will the new owner be willing tae consider the previous tenants?”

Mr. Marcus waved his hand, the flash of a gold ring catching the light from the window. “Doubtful—they’ll be tearing down these old bricks tae make a boutique hotel.”

Paislee cursed aloud.

Brody handed her his toffee with a disappointed look on his sweet face. “Ah, Mum, that’s fifty pence for the swear jar.”

Paislee stood in the middle of Cashmere Crush, reeling from all directions. She eyed the men around her and ground her teeth together. Shawn Marcus retreated two steps closer to the front door.

“Wait just a”—she glanced at her wide-eyed son—“a blasted minute. Have you talked tae the others yet?” She gestured to her left and the shared wall with her neighbor James, who owned the leather repair shop. She’d lined both long walls with shelves for vibrantly colored yarn and it brightened the interior, even without the overhead lights on.

“You were the last stop,” Mr. Marcus said. “But the only one tae actually open yer letter.” His mouth turned down in disapproval, as if by reading his notice she’d been impolite.

Detective Inspector Zeffer wore the slightest frown as he observed them, his hands folded before him.

Brody tugged on her sweater. “Mum! We have tae go.”

“Where?” the detective asked.

“School.” Brody crossed his arms. “We are always late.”

“Not always,” Paislee said, her face on fire as all four of the men looked to her with judgment. Really?

They had no idea what it was like to raise a son and run a business and a home.

And if she lost this location for Cashmere Crush? She’d lose the eight years she’d spent building up her clientele; the loyal group of crafters were now like family.

“If ye want, I can drop him off,” Jerry offered from behind her. “I only have two more stops tae make.”

“Naw, I can do it,” Paislee said, feeling the pressure. “I’ll need you all tae go now, though.” She shooed the detective and her landlord toward the door.

Her grandpa adjusted his tam, but his brown boots didn’t move. What on this green earth was she supposed to do about him?

Jerry made for the back door and called out his good-bye, apologizing about the yarn.

She lifted her hand, but the yarn had moved to the last worry on her list. “Tomorrow, then, Jerry. Cheers.”

Mr. Marcus shuffled awkwardly before just ducking out. What could the man possibly have to say that she would want to hear? Thirty days to be gone?

Detective Inspector Zeffer hesitated, his hand on the tabletop. She could feel his need to fix whatever had just happened, but since no crime had been committed his services weren’t needed. He squared his shoulders and followed her landlord out. Paislee didn’t bother saying good-bye—she had no words for the havoc those two men had just created in her life.

No lease, and a new responsibility.

“You’ll have tae come with us,” she told Grandpa Angus.

He didn’t argue but didn’t agree; he just picked up his suitcase.

She locked the door and herded Brody and Grandpa Angus to where she’d parked the Juke behind the store.

Brody eyed her grandfather before offering the old stranger the front seat, which the man refused, to Brody’s relief.

She gave her son a nod of approval at the show of good manners, and they drove the mile to Fordythe, a single-story brick building that was very long, with central double doors that had been painted blue. A fenced lawn was to the left for the bairns to play on. She followed the paved drive where parents could drop off their children in the morning and then pick them up again at three thirty—normally there were two attendants and the teachers took turns to supervise.

The last attendant was just going inside and Brody dashed out without so much as a see-you, his black backpack over his arm.

“He only has one more year of primary school,” she shared, her voice thick.

Her grandfather played mute.

What was she supposed to do with him? She couldn’t take Grandpa Angus back to her house; she didn’t know him from Adam. Her home was dear to her, and while she didn’t have an abundance of new things, she treasured what she had.

What if he took off with the telly?

“Could you please sit up here so I dinnae feel like a cabby?”

With a grunt, Grandpa Angus opened the rear passenger door and climbed into the front passenger side. He stared straight ahead, his jaw hidden behind a full silver beard.

He smelled of the sea and she was reminded sharply that while things for her had been tight, for him they’d been worse.

“Would ye like tae get a bite tae eat?” When was the last time he’d eaten?

He didn’t reply.

The digital clock on the car radio read 9:15. “I have customers in this morning.” And Isla, drat. “I’ll pick up some breakfast sandwiches from the market, and coffee—it’s a coffee kind of day; then we’ll go tae Cashmere Crush.”

He still said nothing.

“I cannae help, if you don’t talk tae me.” She wanted to keep him off the streets, aye, but what could she do?

“I dinnae want yer help. Just let me oot somewhere.”

“And have the detective bring ye back?” Her voice pitched high. “He knows who ye belong tae now.”

“Dinnae fesh yerself.” He removed his tam and focused out the window at the passing businesses in stone or brick. Nairn had once been a popular fishing village.

“Don’t worry? Really?” That would be impossible now that she was aware he was in trouble. “Where’s Craigh?”

He said not a word.

Paislee drove the half mile to the small market near her shop. She could practically hear the wheels in his silver head churn. She had no time for more drama, but it seemed impossible to avoid today.

Paislee parked and faced her grandpa. Her memories of him were vague, and colored by Granny’s refusal to discuss him. She’d never outright disparaged him—but the mutterings whenever his name arose were enough for Paislee to realize he was not a welcome subject.

The last time she’d seen him had been at Granny’s funeral, and Paislee had been such a mess that she could hardly recall the proceedings. Granny had been sick for months before she’d passed. Father Dixon had managed things, thank heaven.

Paislee’s grandmother had not once asked to see her husband before she’d died. And why was that?

In a final act of love, Gran had bequeathed her home to Paislee, saying that nobody should fear being without a roof over their head, not if she could help it.

This couldnae be what ye meant, Gran.

Grandpa Angus finally looked at her. Clear brown eyes behind black glasses, silver hair and beard, deep wrinkles of a hard life furrowed his cheeks and brow.

“You can come in with me, and choose for yourself, or wait here and I’ll be right back with two bacon butties and coffee. Aye?”

He nodded his thanks and stayed in the car.

Paislee kept her keys and cardigan as she ran inside the small market. It had odds and ends that a tourist might need—travel-sized shampoo, toothbrush and toothpaste, razors.Would her grandfather need any of those things?

Where the devil was Craigh?

She stepped up to the register and smiled at Colleen, fresh faced at twenty. Paislee would kill for the girl’s boundless energy.

“Mornin’. Two bacon butties, two coffees.”

“Hiya, Paislee,” Colleen said, bouncing behind the counter as she gathered and rang up Paislee’s order. The smell of the bacon made her mouth water, despite already having had a bit of breakfast earlier with Brody.

Colleen handed her the bag and two coffees in a cardboard box.

“Thanks!”

Colleen grinned and greeted the next customer in the queue.

Paislee took the goodies back to the Juke, apprehensive that maybe her grandpa had made a dash for it while she was gone.

Where would he go?

It was obvious that if he was sleeping in the park in cool spring his options were limited.

She breathed a sigh of relief when she saw the outline of his hat now back on his head and the glint of silver at his beard. He didn’t offer a smile, though he did reach across the inside of the car to open her door for her.

She climbed in and handed him the coffees first, then the bag.

“I hope you’re hungry. These are huge.”

He gave a nod and swallowed hard, his fingers trembling on the cardboard tray for the hot coffee.

She averted her eyes before she said something to offend his pride.

There w. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved