Chapter 1

September 14, 1899

The seemingly impossible had happened—and with so little fanfare, it might almost have gone unnoticed. Except that overnight, the world had changed and would never be the same.

And now here I stood, on a hillside that commanded broad views of Staten Island and the entrance of New York Harbor, feeling as bereft as the fallen leaves that rustled across the ground in doleful whispers. A chill penetrated my wool carriage dress and jacket, but I neither hugged my arms around me nor tugged my collar higher. Instead, I allowed the cold and damp to seep into my bones, a physical reminder of the current state of my soul. Dominating the view before me, the granite stones of the Vanderbilt Family mausoleum mirrored a cheerless sky—the clouds as gray as steel rails, their edges as black as coal-fed locomotives.

Cornelius Vanderbilt II lay dead—“Uncle Cornelius,” as I’d always called him, even though, in fact, we had been cousins twice or thrice removed. How would this family ever go on without him?

Footsteps clattered as Aunt Alice, her grown children, and Uncle Cornelius’s siblings and their families filed from the mausoleum. I turned away, unable to school my features to the stoic calm necessary for maintaining one’s dignity. In fact, my facial muscles ached from the effort of holding them steady. Aunt Alice’s eyes were red-rimmed, but not a tear had fallen since we had left the Fifth Avenue mansion that morning. Only Gladys, Cornelius and Alice’s youngest child, had allowed her emotions their escape, but even she had wept only quietly during the funeral and, again here, during the interment.

“You all right, Em?” Brady Gale, my half brother, came up behind me and put an arm around my shoulders.

I shook my head and leaned against his shoulder, a few inches higher than my own. “No. Are you?”

“No.” A gravelly sigh escaped him. The wind swept up leaves in a tiny whirlwind that hit a gravestone and scattered. “I know at first the old man only gave me a job because of you. That he probably would rather not have.”

“That’s not true. Uncle Cornelius—”

“It’s all right. I know what I was. And I know how I’ve changed, because of you and because of him.”

Yes—and no. Brady had once drunk too much, caroused too much, fought too much. In the end, though, it hadn’t been me or Uncle Cornelius or any one person who had inspired him to alter his ways. It had been life and the frightening turn it had taken; it had been Brady himself who, when faced with a choice, had chosen correctly.

He went on after a grim laugh. “He’s always had the utmost faith in you, Em, and gradually, ever so slowly, he extended that faith to me. I’ll never forget that—” He broke off, swallowing hard and then clenching his teeth. His head bowed, his straight sandy-blond hair fell forward over his brow, despite his attempts to tame it with Macassar oil. I looked away, allowing him his moment of grief.

From across the landscaped clearing in front of the mausoleum, I caught my cousin Neily’s eye. He stood alone beside some trees, looking as forlorn as those gray branches against the grayer sky. He’d observed the funeral at St. Bartholomew’s Church in the City from the back row, and I knew he was waiting now until everyone else vacated the area to pay his last respects to his father.

The very same father who had disinherited him only a few years earlier. I had wondered if he would even come today, and would not have thought him unjustified in staying home. Neily’s mustache and beard twitched as he returned my glance, revealing the bitter tug of his lips. He gave me half a shrug before dropping his gaze to the ground. He’d come alone, his wife and young son having remained in Newport. Grace, Neily’s wife, had been the reason for the family rift, and Aunt Alice made no secret of her belief that Neily had caused his father’s early death. The first paralytic stroke had occurred the day Neily had announced his engagement to his parents. The final one, only two days ago.

Like ashes scattering on a gust of wind, the black-clad assemblage broke apart to board the coaches for the short ride to the ferry, which would take us back to Manhattan. Brady and I rode with my cousin Gertrude and her husband, Harry Whitney. He held her hand. She rested her cheek against his shoulder. Grief hovered in Gertrude’s eyes and tightened the lines of her mouth, but like her mother, she buried the full extent of her grief beneath a veil of dignity. We spoke little. I planned to linger only briefly in the City to say my good-byes. The train ride home to Rhode Island loomed ahead of me. It was sure to be a bleak journey.

Yet, when we finally arrived at the Fifth Avenue mansion, Alfred, Cornelius’s primary heir, took me aside in the central hall while the others filed into the drawing room.

“You’ll stay another night, won’t you, Emmaline?”

I shook my head as I pulled my gloves from my hands. “I should be getting back. Besides, there are enough people here to console your mother. You don’t need me.”

“It isn’t that—not just that—anyway.” He offered me something approaching a smile. Younger than Neily, and younger than me for that matter, Alfred Vanderbilt was now the head of the family. He and Uncle William Vanderbilt would jointly hold the reins of the New York Central Railroad and dictate the company’s major decisions. And yet, to me, he was still my little cousin Alfred.

I sensed in him a discomfort that bordered on embarrassment and couldn’t fathom a reason for it. “Alfred, if something is wrong, please just come out with it. Nothing can be worse than today.”

“It’s nothing bad, actually. It’s just so hard to speak of. So unreal and disquieting.”

“Yes, I understand.” I touched his wrist briefly. Alfred and I had never been as close as Neily and I, had never truly been confidants.

“It seems Father mentioned you in his will. Brady too. Our lawyer said so. The reading is tomorrow morning and I think you should stay and hear it.”

“Oh.” I couldn’t have been more dumbfounded. While it didn’t surprise me that Uncle Cornelius might have left me a token gift, I wouldn’t have thought it significant enough to warrant me staying to hear the reading. My thoughts immediately went to Neily, who had been existing outside the family circle for the past four years. “What about your brother?”

Alfred knew which of his two brothers I meant. He shook his head. “I’ll be surprised if Father left him anything at all. But don’t worry, Emmaline, I won’t let Neily suffer. I intend to—”

He broke off at the sound of his sister Gertrude’s voice. “Alfred? Where are you? You’re needed in the drawing room.” She found us in the shadow of the Grand Staircase, a columned, circular structure carved from pure white Caen stone that dominated the Great Hall. She slipped her arm through her brother’s. “Come. Mama is asking for you. You too, Emmaline. You know how you’re often able to calm her when the rest of us can’t.” She chuckled lightly, without mirth. “You and Gladys. Her favorites.”

“I’m hardly that,” I said, and fell into step beside them.

* * *

That next morning, the family and I gathered in the library, a large room so heavily gilded, carved, and filled with sumptuous textures that I’d always found it difficult to concentrate amid such distraction. Today I barely saw the fortune’s worth of treasures as we settled in. Brady and I sat together on one of the sofas, the furniture having been rearranged so that the seating all faced the rosewood and inlaid ivory desk. The man who occupied the desk chair, Uncle Cornelius’s lawyer, stared silently back at us from within the pockets of sallow flesh that surrounded his eyes.

We were waiting . . .

“Sorry I’m late.” Neily spoke in a murmur to no one in particular and shrugged himself into a high-backed chair with a lion’s head carved into the apex of the frame. Gertrude frowned and looked away. Alfred, Gladys, and youngest brother, Reggie, appeared relieved. Alice Vanderbilt gave no reaction, as if Neily didn’t exist; as if no one, or perhaps merely a ghost, occupied that lion’s-head chair.

The lawyer cleared his throat and began. Names, figures, and properties touched my ears but made little impression. I could think only of Uncle Cornelius, of his life cut short so cruelly, and of how this family would continue without him. Then I heard my name spoken. “To Emmaline Cross, whom I consider my niece and has often been like a daughter to me, I leave the sum of ten thousand dollars and an additional ten thousand in New York Central stock.”

My mouth fell open. The blood rushed in my ears. The lawyer continued, but I remained fixed on what I’d heard, or thought I’d heard. Surely, it must be a mistake. Oh, next to the Vanderbilt millions, such a sum might seem trifling, but to me . . .

My heart pounded against my stays. What would I do with so much money? I couldn’t begin to fathom it. I almost didn’t wish to. One would think I would be overjoyed at such a boon. But thus far, my life had had a routine, a method, an established order of the way things were done. Suddenly all of my meticulous arranging and scheduling and thrifty budgeting fell in jumbled heaps around me.

Before I could contemplate any further, for good or ill, the sound of Brady’s name brought me tumbling headlong out of my thoughts. Uncle Cornelius left him a sum nearly as generous as mine. Brady smiled even as his eyes shone with moisture, and it made me gladder than I could express that Uncle Cornelius had embraced my half brother, who was related to me through our mother, and not a Vanderbilt at all, as part of the family.

“To Cornelius Vanderbilt the third . . .”

Neily sat up straighter, while his siblings suddenly found the floor at their feet terribly interesting. His mother, on the other hand, continued staring straight ahead, as if once again her eldest living son did not exist.

“. . . I leave the sum of one half of one million dollars and a further million in trust . . .”

A vast sum, staggering from my point of view, and my first thought was thank goodness his father hadn’t cut him off entirely. But one glance at Neily’s tight-lipped expression, the ruddy color that flooded his face, dissuaded me of that conclusion.

To him, the amount could only be perceived as a slight. His siblings would each receive many millions. Alfred received the bulk of the fortune—an astonishing 70 million, plus most of the shares in the New York Central Railroad, along with countless other assets. Neily would receive none of that. He could live on what his father left him, certainly. Or so an ordinary individual might think. No, it wasn’t so much the money, or the lack of it, but the sentiment behind Cornelius’s bequest to his eldest son; the insult that now, in order to maintain the lifestyle he and Grace were accustomed to, they would have to continue living off her dowry, essentially making Neily a “kept” man. Despite his having attained a master’s degree in engineering at Yale, and proven himself to be a brilliant innovator, he could never earn the kind of money needed to run several estates and travel back and forth to Europe each Season.

Uncle Cornelius had had the last word, a reprimand from the grave to which there could be no response.

* * *

That afternoon, I boarded the northbound train considerably wealthier than I had ever dreamed of being. From now on, I would have significantly fewer financial worries, as well as the ability to increase my charitable contributions. My altered circumstances made the trek north a bit less desolate, though I could not say I felt anything approaching cheerfulness. But the children of St. Nicholas Orphanage, to whom I regularly gave what I could, would certainly benefit from Uncle Cornelius’s largesse. So would Nanny, my housekeeper, and Katie, my maid-of-all-work. Far from being mere servants in my household, they were family, kindred spirits, and beloved figures in my life. And from now on, they would no longer have to go without. None of us would. The house could be repaired when needed, fading furniture replaced, our larder kept full.

Despite what might be considered my good fortune, I spent the next few days enveloped in a deep sense of gloom. All the money in the world could not make up for so great a loss, neither to the country nor to myself. However much members of the Four Hundred might be criticized for their extravagant lifestyles and lack of empathy toward the lower classes, I knew my uncle Cornelius had not been such a man. Quite the contrary. If anything, he had been criticized by his own peers for his lack of vices. He’d shown no interest in yachting or horse racing, extravagant late-night parties, excessive spending—with the exceptions of his homes in New York and Newport, where no expense had been spared—or any of those overindulgences for which the Four Hundred were infamous. It had even been a rare day that found him on the golf course or the tennis court. Rather, when not working diligently to expand the family business concerns, he had dedicated himself, along with Alice, to philanthropic projects to the benefit of many.

Each night, in my restless dreams, as well as waking moments, I kept picturing him as I’d seen him last: serene, composed, his face surrounded by the satin lining of his coffin. His had been a well-favored countenance, some might even have said handsome, but there had been nothing there to suggest greatness—at least, no more so than the average individual. Yet, no one had ever doubted that greatness. How could such a formidable man, who could command a room with little more than a soft word—even in illness—be so suddenly and irrevocably gone?

Meanwhile, I went through the motions of daily life.

“You’re not eating enough,” Nanny pointed out to me on the third morning I’d been home. She gestured toward my plate of half-eaten toast and congealed eggs. “It won’t help anyone for you to starve yourself. It won’t bring your uncle back.”

I glanced up from the newspaper I’d been pretending to read, the black print smudging my fingertips but failing to leave any impression on my brain. “I’m not starving myself. Don’t be melodramatic.”

Nanny shrugged, but a silvery eyebrow rose above her half-moon spectacles in that way she had of chastising me without speaking a word. For an instant, she appeared to me years younger—the nanny who had essentially raised me, while my parents entertained their artist friends at our modest home on Easton’s Point. It had been Nanny who had bandaged my skinned knees and elbows, taught me my letters before I’d gone to school, listened to my childish secrets, and coaxed me to finish whatever had been put on my plate each day. I had known Mary O’Neal all my life, and when I’d inherited my current home, Gull Manor, from my great-aunt Sadie, I could think of no one else I’d rather have there with me as my housekeeper and my friend.

But she often knew me better than I knew myself, and at times I found that irritating. “Fine.” I picked up my toast and took another bite. The bread tasted like dust, the blueberry jam like paste.

“Katie,” Nanny called into the kitchen, “please bring Miss Emma another plate of eggs. She let the first ones go cold.”

“Never mind, Katie,” I countermanded. “Nanny, I’m fine. Just not hungry. I promise I’ll eat a good lunch.”

“Hmph.”

The ringing of our telephone saved me from further debate, and I hurried out of the morning room and to the front of the house. There, however, I stopped in my tracks while the jangling continued, for in the alcove beneath my staircase lurked another reminder of Uncle Cornelius’s kindness. When his summer cottage, The Breakers, had been built on Bellevue Avenue, he’d had electricity and telephones installed. At the same time, he had insisted on installing one of those latter devices here at Gull Manor. I had protested. It had seemed so extravagant, but he had adamantly insisted.

“You’re all alone out there on Ocean Avenue, Emmaline,” he’d said in that firm way of his. “You and that housekeeper of yours, two defenseless women living on the edge of the ocean far from town. Anything could happen. Do you think I’d ever forgive myself if a simple telephone call might have saved you?”

There had, of course, been no arguing with that.

I hurried the last few feet along the corridor and snatched the ear trumpet from its cradle. “Emma Cross here.”

“Emma, it’s Grace.”

My heart lurched. Why would Neily’s wife be calling me, especially first thing in the morning? I happened to know she rarely rose before ten o’clock. And like most members of the Four Hundred, New York’s highest society, Grace Wilson Vanderbilt disdained using telephones, considering them intrusive and vulgar. Typically, she had her social secretary, butler, or housekeeper make her telephone calls for her.

“Grace, has something happened? Are you and Neily all right? Little Corneil? Where are you?”

“Emma, calm down. We’re in Newport, at Beaulieu. And we’re fine. I’m terribly sorry to worry you, but I’ve a favor to ask. An important one.”

“Goodness, Grace. I’ll admit you did give me a fright.” I leaned against the wall while my racing heart gradually slowed. “What can I do for you?”

“It’s Neily.” I heard a combination of distress and resignation in her voice.

“I thought you said nothing is wrong.”

“Nothing is . . . yet. But there’s a party at Wakehurst tomorrow night and Neily is insisting on going.”

“Now, while he’s in mourning?”

“That’s what I said. No matter the situation between his parents and us, he just lost his father and has no business socializing. He’s being so stubborn about it. He insists he lost his father years ago, and therefore has nothing more to mourn now. But you and I both know it’s not as simple as that, or he wouldn’t have gone to the funeral. I’m afraid he’ll drink too much, something will set him off, and he’ll end up doing or saying something regrettable.”

“Oh, Grace, has he been drinking?” I knew all too well how some men resorted to alcohol in times of strife.

“No more than usual,” Grace assured me, but went on to add, “not yet, anyway. But I’m afraid being out among people might encourage him to overindulge. He’s not in a good state of mind. He’s angry, and whether he wishes to admit it or not, he’s also grieving.”

Angry—yes. As for grieving . . . Grace was right in that however much Neily might deny it, he had lost a parent. He must not only be mourning his father’s loss, but also regretting the lost opportunity to ever make amends.

“I’ll talk to him, Grace. I’ll try to make him see the folly of attending this party.”

“Talk to him? No, that’s not what I’m asking. He won’t listen. His mind is made up.”

“Then . . . what do you wish me to do?”

“Come with us, Emma. Please. At least if you’re there, you can prevent him from doing something foolish. If he gets in a state and I try to restrain him, he’ll consider it nagging. Coming from you, he’ll see the sense in it.”

“Grace, I don’t know . . .” The mere thought of attending a function among the Four Hundred exhausted me. In fact, it seemed callous and selfish of James Van Alen to hold a party at Wakehurst at this, of all times. True, the event would have been planned weeks ago, and true again, the remaining members of the Four Hundred would be leaving Newport shortly in favor of their winter homes, so that a postponement wouldn’t have been practical. Had it been me, however, I would have canceled and sent my regrets to the invitees, many of whom had prospered as a result of their acquaintance with Cornelius Vanderbilt.

“Emma, please. I’m frightened for Neily’s sake.”

“I do have to work the next morning, you realize.”

“Pooh. You work for your beau, and he’ll forgive you an hour’s tardiness this one time. Please do this for me.”

Her quiet pleas broke through my reservations, and I let out a sigh. “All right, I’ll come.”

“Thank you, Emma. I’ll send over an outfit for you to wear. It’s a Renaissance theme.”

I very nearly groaned out loud. “A fancy-dress ball?”

“No, not exactly. He wishes us to wear clothing that is reminiscent of the period. Inspired by it, but not what one would call a costume, because as he said when I inquired, that would be inelegant. Van Alen’s calling it an Elizabethan Fete. You know how he is about all things English. The invitation came on parchment, handwritten in old-style script, in metered rhyme, no less. Would you like me to read it to you?”

“No, thank you,” I quickly replied. I hoped I wouldn’t feel pressured to dance, and perhaps I could keep an eye on Neily while remaining along the edges of the festivities. My heart certainly wouldn’t be in it, but Neily and Grace were dear to me, and perhaps Neily would be persuaded to leave early. With that thought to bolster me, I said my good-byes, hung up, and went about my day. But a sense of misgiving never quite left me.

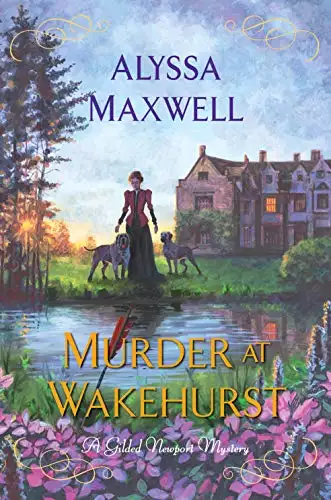

Chapter 2

Despite Grace’s assurances that it would not be a fancy-dress occasion, I admit I had feared what she would send for me to wear to James Van Alen’s fete. Would my neck be imprisoned in a stiff, scratchy ruff that would leave my skin irritated for days to come? Would the weight of the skirts drag at my every step? Or perhaps a steel farthingale would deny me the relief of sitting for even a moment.

I needn’t have worried. She sent a simple forest-green silk gown with an overskirt parted in the front to show off the beautiful details of a lighter green damask beneath. Over it went a rose velvet jacket, beribboned and beaded, which flattered my proportions, while the tight sleeves, which puffed at the shoulders and elbows, made me feel like a princess of yore.

Nanny put up my hair with my enameled combs and added tiny rhinestones, which she had attached to hairpins, for extra sparkle. I’d have to go without my diamond teardrop earrings, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved