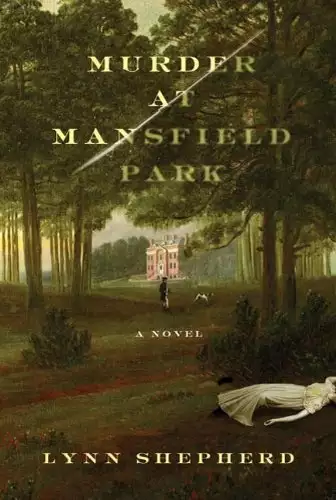

Murder at Mansfield Park

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

"Nobody, I believe, has ever found it possible to like the heroine of Mansfield Park." --Lionel Trilling

In this ingenious new twist on Mansfield Park, the famously meek Fanny Price--whom Jane Austen's own mother called "insipid"--has been utterly transformed; she is now a rich heiress who is spoiled, condescending, and generally hated throughout the county. Mary Crawford, on the other hand, is now as good as Fanny is bad, and suffers great indignities at the hands of her vindictive neighbor. It's only after Fanny is murdered on the grounds of Mansfield Park that Mary comes into her own, teaming-up with a thief-taker from London to solve the crime.

Featuring genuine Austen characters--the same characters, and the same episodes, but each with a new twist--MURDER AT MANSFIELD PARK is a brilliantly entertaining novel that offers Jane Austen fans an engaging new heroine and story to read again and again.

Release date: July 14, 2010

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Murder at Mansfield Park

Lynn Shepherd

About thirty years ago Miss Maria Ward, of Huntingdon,

with only seven thousand pounds, had the good luck

to captivate Sir Thomas Bertram, of Mansfield Park, in

the county of Northampton, and to be thereby raised

to the rank of a baronet's lady, with all the comforts and

consequences of an handsome house and large income. All

Huntingdon exclaimed on the greatness of the match, and

her uncle, the lawyer, himself, allowed her to be at least three

thousand pounds short of any equitable claim to it. She had

two sisters to be benefited by her elevation, and her father

hoped that the eldest daughter's match would set matters

in a fair train for the younger. But, though she possessed

no less a fortune, Miss Julia's features were rather plain

than handsome, and in consequence the neighbourhood

was united in its conviction that there would not be such

another great match to distinguish the Ward family.

Unhappily for the neighbourhood, Miss Julia was fated

to confound their dearest expectations, and to emulate

her sister's good luck, by captivating a gentleman of both

wealth and consequence, albeit a widower. Within a

twelvemonth after Miss Ward's nuptials her younger sister

began upon a career of conjugal felicity with a Mr Norris,

his considerable fortune, and young son, in the village

immediately neighbouring Mansfield Park. Miss Frances

fared yet better. A chance encounter at a Northampton ball

threw her in the path of a Mr Price, the only son of a great

Cumberland family, with a large estate at Lessingby Hall.

Miss Frances was lively and beautiful, and the young man

being both romantic and imprudent, a marriage took place

to the infinite mortification of his father and mother, who

possessed a sense of their family's pride and consequence,

which equalled, if not exceeded, even their prodigious

fortune. It was as unsuitable a connection as such hasty

marriages usually are, and did not produce much happiness.

Having married beneath him, Mr Price felt justly entitled

to excessive gratitude and unequalled devotion in his wife,

but he soon discovered that the young woman he had

loved for her spirit, as much as her beauty, had neither the

gentle temper nor submissive disposition he and his family

considered his due.

Older sages might easily have foreseen the natural

sequel of such an inauspicious beginning, and despite the

fine house, jewels and carriages that her husband's position

afforded, it was not long before Miss Frances, for her part,

perceived that the Prices could not but hold her cheap, on

account of her lowly birth. The consequence of this, upon

a mind so young and inexperienced, was but too inevitable.

Her spirits were depressed, and though her family were not

consumptive, her health was delicate, and the rigours of

the Cumberland climate, severely aggravated by a difficult

lying-in, left young Mr Price a widower within a year of

his marriage. He had not been happy with his wife, but

that did not prevent him being quite overcome with

misery and regret when she was with him no more, and

the late vexations of their life together were softened by her

suffering and death. His little daughter could not console

him; she was a pretty child, with her mother's light hair and

blue eyes, but the resemblance served only to heighten his

sense of anguish and remorse. It was a wretched time, but

even as they consoled their son in his affliction, Mr and Mrs

Price could only congratulate themselves privately that a

marriage contracted under such unfortunate circumstances

had not resulted in a more enduring unhappiness. Having

consulted a number of eminent physicians, the anxious

parents soon determined that the young man would be

materially better for a change of air and situation, and the

family having an extensive property at the West Indies, it

was soon decided between them that his wounded heart

might best find consolation in the novelty, exertion, and

excitement of a sea voyage. Some heart-ache the widowerfather

may be supposed to have felt on leaving his daughter,

but he took comfort in the fact that his little Fanny would

have every comfort and attention in his father's house.

He left England with the probability of being at least a

twelvemonth absent.

And what of Mansfield at this time? Lady Bertram had

delighted her husband with an heir, soon after Miss Frances'

marriage, and this joyful event was duly followed by the

birth of a daughter, some few months younger than her

little cousin in Cumberland. One might have imagined Mrs

Price to have enjoyed a regular and intimate intercourse

with her sisters at Mansfield during this interesting period,

but her husband's family had done all in their power to

discourage any thing more than common civility, and

despite Mrs Norris's sanguine expectations of being ‘every

year at Lessingby', and being introduced to a host of great

personages, no such invitation was ever forthcoming. Mrs

Price's sudden death led to an even greater distance between

the families, and when news finally reached Mansfield that

young Mr Price had fallen victim to a nervous seizure on

his journey back to England—intelligence his parents had

not seen fit to impart themselves—Mrs Norris could not

be satisfied without writing to the Prices, and giving vent

to all the anger and resentment that she had pent up in

her own mind since her sister's marriage. Had Sir Thomas

known of her intentions, an absolute rupture might have

been prevented, but as it was the Prices felt fully justified in

putting an end to all communication between the families

for a considerable interval.

One can only imagine the mortifying sensations that Sir

Thomas must have endured at such a time, but all private

feelings were soon swallowed up by a more public grief.

Mr Norris, long troubled by an indifferent state of health,

brought on apoplexy and death by drinking a whole bottle

of claret in the course of a single evening. There were some

who said that a long-standing habit of self-indulgence had

lately grown much worse from his having to endure daily

harangues from his wife at her ill-treatment by the Prices,

but whatever the truth of this, it is certain that no such

rumour ever came to Mrs Norris's ear. She, for her part,

was left only with a large income and a spacious house, and

consoled herself for the loss of her husband by considering

that she could do very well without him, and for the loss of

an invalid to nurse by the acquisition of a son to bring up.

At Mansfield Park a son and a daughter successively

entered the world, and as the years passed, Sir Thomas

contrived to maintain a regular if unfrequent correspondence

with his brother-in-law, Mr Price, in which he learned of

little Fanny's progress with much complacency. But when

the girl was a few months short of her twelfth birthday,

Sir Thomas, in place of his usual communication from

Cumberland, received instead a letter in a lawyer's hand,

conveying the sorrowful information that Mr and Mrs

Price had both succumbed to a putrid fever, and in the next

sentence, beseeching Sir Thomas, as the child's uncle, and

only relation, to take the whole charge of her. Sir Thomas

was a man of honour and principle, and not insensible

to the claims of duty and the ties of blood, but such an

undertaking was not to be lightly engaged in; not, at least,

without consulting his wife. Lady Bertram was a woman

of very tranquil feelings, guided in every thing important

by Sir Thomas, and in smaller day-to-day concerns by her

sister. Knowing as he did Mrs Norris's generous concern

for the wants of others, Sir Thomas elected to bring the

subject forward as they were sitting together at the tea-table,

where Mrs Norris was presiding. He gave the ladies the

particulars of the letter in his usual measured and dignified

manner, concluding with the observation that ‘after due

consideration, and examining this distressing circumstance

in all its particulars, I firmly believe that I have no other

alternative but to accede to this lawyer's request and bring

Fanny to live with us here, at Mansfield Park. I hope, my

dear, that you will also see it in the same judicious light.'

Lady Bertram agreed with him instantly. ‘I think we

cannot do better,' said she. ‘Let us send for her at once. Is

she not my niece, and poor Frances' orphan child?'

As for Mrs Norris, she had not a word to say. She

saw decision in Sir Thomas's looks, and her surprise and

vexation required some moments' silence to be settled into

composure. Instead of seeing her first, and beseeching her

to try what her influence might do, Sir Thomas had shewn

a very reasonable dependence on the nerves of his wife,

and introduced the subject with no more ceremony than

he might have announced such common and indifferent

news as their country neighbourhood usually furnished.

Mrs Norris felt herself defrauded of an office, but there

was comfort, however, soon at hand. A second and most

interesting reflection suddenly occurring to her, she resumed

the conversation with renewed animation as soon as

the tea-things had been removed.

‘My dear Sir Thomas,' she began, with a voice as well

regulated as she could manage, ‘considering what excellent

prospects the young lady has, and supposing her to possess

even one hundredth part of the sweet temper of your own

dear girls, would it not be a fine thing for us all if she were

to develop a fondness for my Edmund? After all, he will in

time inherit poor Mr Norris's property, and she will have

her grandfather's estate, an estate which can only improve

further under your prudent management. It is the very

thing of all others to be wished.'

‘There is some truth in what you say,' replied Sir Thomas,

after some deliberation, ‘and should such a situation arise,

no-one, I am sure, would be more contented than myself.

But whatever its merits, I would not wish to impose such a

union upon any young person in my care. Every thing shall

take its course. All the young people will be much thrown

together. There is no saying what it may lead to.'

Mrs Norris was content, and every thing was considered

as settled. Sir Thomas made arrangements for Mr Price's

lawyer to accompany the girl on the long journey to

Northampton-shire, and three weeks later she was delivered

safely into her uncle's charge.

Sir Thomas and Lady Bertram received her very kindly,

and Mrs Norris was all delight and volubility and made

her sit on the sopha with herself. Their visitor took care

to shew an appropriate gratitude, as well as an engaging

submissiveness and humility. Sir Thomas, believing her quite

overcome, decided that she needed encouragement, and

tried to be all that was conciliating, little thinking that, in

consequence of having been, for some years past, Mrs Price's

constant companion and protégée, she was too much used to

the company and praise of a wide circle of fine ladies and

gentlemen to have any thing like a natural shyness. Finding

nothing in Fanny's person to counteract her advantages of

fortune and connections, Mrs Norris's efforts to become

acquainted with her exhibited all the warmth of an

interested party. She thought with even greater satisfaction

of Sir Thomas's benevolent plan; and pretty soon decided

that her niece, so long lost sight of, was blessed with talents

and acquirements in no common degree. And Mrs Norris

was not the only inmate of Mansfield to partake of this

generous opinion. Fanny herself was perfectly conscious of

her own pre-eminence, and found her cousins so ignorant

of many things with which she had been long familiar, that

she thought them prodigiously stupid, and although she

was careful to utter nothing but praise before her uncle and

aunt Bertram, she always found a most encouraging listener

in Mrs Norris.

‘My dear Fanny,' her aunt would reply, ‘you must not

expect every body to be as forward and quick at learning

as yourself. You must make allowance for your cousins, and

pity their deficiency. Nor is it at all necessary that they

should be as accomplished as you are; on the contrary, it is

much more desirable that there should be a difference. You,

after all, are an heiress. And remember that, if you are ever so

forward and clever yourself, you should always be modest.

That is by far the most becoming demeanour for a superior

young lady.'

As Fanny grew tall and womanly, and Sir Thomas made

his yearly visit to Cumberland to receive the accounts, and

superintend the management of the estate, Mrs Norris did

not forget to think of the match she had projected when

her niece's coming to Mansfield was first proposed, and

became most zealous in promoting it, by every suggestion

and contrivance likely to enhance its desirableness to

either party. Once Edmund was of age Mrs Norris saw

no necessity to make any other attempt at secrecy, than

talking of it every where as a matter not to be talked of at

present. If Sir Thomas saw any thing of this, he did nothing

to contradict it. Without enquiring into their feelings, the

complaisance of the young people seemed to justify Mrs

Norris's opinion, and Sir Thomas was satisfied; too glad to

be satisfied, perhaps, to urge the matter quite so far as his

judgment might have dictated to others. He could only

be happy in the prospect of an alliance so unquestionably

advantageous, a connection exactly of the right sort, and

one which would retain Fanny's fortune within the family,

when it might have been bestowed elsewhere. Sir Thomas

knew that his own daughters would not have a quarter as

much as Fanny, but trusted that the brilliance of countenance

that they had inherited from one parent, would more than

compensate for any slight deficiency in what they were to

receive from the other.

The first event of any importance in the family happened

in the year that Miss Price was to come of age. Her elder

cousin Maria had just entered her twentieth year, and Julia

was some six years younger. Tom Bertram, at twenty-one,

was just entering into life, full of spirits, and with all the

liberal dispositions of an eldest son, but a material change

was to occur at Mansfield, with the departure of his younger

brother, William, to take up his duties as a midshipman on

board His Majesty's Ship the Perseverance. With his open,

amiable disposition, and easy, unaffected manners William

could not but be missed, and the family was prepared to find

a great chasm in their society, and to miss him decidedly. A

prospect that had once seemed a long way off was soon

upon them, and the last few days were taken up with the

necessary preparations for his removal; business followed

business, and the days were hardly long enough for all the

agitating cares and busy little particulars attending this

momentous event.

The last breakfast was soon over; the last kiss was given,

and William was gone. After seeing her brother to the final

moment, Maria walked back to the breakfast-room with a

saddened heart to comfort her mother and Julia, who were

sitting crying over William's deserted chair and empty plate.

Lady Bertram was feeling as an anxious mother must feel,

but Julia was giving herself up to all the excessive affliction

of a young and ardent heart that had never yet been

acquainted with the grief of parting. Even though some

two years older than herself, William had been her constant

companion in every childhood pleasure, her friend in every

youthful distress. However her sister might reason with her,

Julia could not be brought to consider the separation as any

thing other than permanent.

‘Dear, dear William!' she sobbed. ‘Who knows if I will

ever behold you again! Those delightful hours we have

spent together, opening our hearts to one another and

sharing all our hopes and plans! Those sweet summers when

every succeeding morrow renewed our delightful converse!

How endless they once seemed but how quickly they have

passed! And now I fear they will never come again! Even if

you do return, it will not be the same—you will have new

cares, and new pleasures, and little thought for the sister you

left behind!'

Maria hastened to assure her that such precious memories

of their earliest attachment would surely never be entirely

forgotten, and that William had such a warm heart that time

and absence must only increase their mutual affection, but

Julia was not to be consoled, and all her sister's soothings

proved ineffectual.

‘We shall miss William at Mansfield,' was Sir Thomas's

observation when he joined them with Mrs Norris in the

breakfast-room, but noticing his younger daughter's distress,

and knowing that in general her sorrows, like her joys, were

as immoderate as they were momentary, decided it was best

to say no more and presently turned the subject. ‘Where are

Tom and Fanny?'

‘Fanny is playing the piano-forte, and Tom has just set

off for Sotherton to call on Mr Rushworth,' replied Maria.

‘He will find our new neighbour a most pleasant,

gentleman-like man,' said Sir Thomas. ‘I sat but ten minutes

with him in his library, yet he appeared to me to have

good sense and a pleasing address. I should certainly have

stayed longer but the house is all in an uproar. I have always

thought Sotherton a fine old place—but Mr Rushworth

says it wants improvement, and in consequence the house

is in a cloud of dust, noise, and confusion, without a carpet

to the floor, or a sopha to sit on. Rushworth was called out

of the room twice while I was there, to satisfy some doubts

of the plasterer. And once he has done with the house, he

intends to begin upon the grounds. Given my own interest

in the subject, we found we had much in common.'

‘What can you mean, Sir Thomas?' enquired Lady

Bertram, roused from her melancholy reverie. ‘I am sure I

never heard you mention such a thing before.'

Sir Thomas looked round the table. ‘I have been

considering the matter for some time, and, if the prospect

is not unpleasant to you, madam, I intend to improve

Mansfield. I have no eye for such matters, but our woods

are very fine, the house is well-placed on rising ground, and

there is the stream, which, I dare say, one might make some

thing of. When I last dined at the parsonage, I mentioned

my plans to Dr Grant, and he told me that his wife's brother

had the laying out of the grounds at Compton. I have since

enquired into this Mr Crawford's character and reputation,

and my subsequent letter to him received a most prompt

and courteous reply. He is to bring his sister with him, and

they are to spend three months in Mansfield. Indeed, they

arrived last night; and I have invited them and the Grants to

drink tea with us this evening.'

The family could not conceal their astonishment, and

looked all the amazement which such an unexpected

announcement could not fail of exciting. Even Julia checked

her tears, and tried to compose herself. Mrs Norris was ready

at once with her suggestions, but was vexed to find that

Sir Thomas had been amusing himself with shaping a very

complete outline of the business. He had, in fact, long been

apprehensive of the effect of his son's departure, and the

contraction of the Mansfield circle consequent thereon. He

had reasoned to himself that if he could find the means of

distracting his family's attention, and keeping up their spirits

for the first few weeks, he should think the time and money

very well spent. Such careful solicitude was quite of a piece

with the whole of his careful, upright conduct as a husband

and father, and the eager curiosity of his family was just

what he wished. Questions and exclamations followed each

other rapidly, and he was ready to give such information as

he possessed, and answer every query almost before it was

put, looking with heartfelt satisfaction on the animated faces

around him. One question, however, he could not answer;

he had never yet seen Mr Crawford, and could not answer

for any thing more than his skill with a pen. Had he known

all that was to come of the acquaintance, Sir Thomas would

surely have forbad him the house.

The Crawfords were not young people of fortune. The

brother had a small property near London, the sister less

than two thousand pounds. They were the children of Mrs

Grant's mother by a second marriage, and when they were

young she had been very fond of them; but, as her own

marriage had been soon followed by the death of their

common parent, which left them to the care of a brother

of their father, a man of whom Mrs Grant knew nothing,

she had scarcely seen them since. In their uncle's house

near Bedford-square they had found a kind home. He was

a single man, and the cheerful company of the brother and

sister ensured that his final years had every comfort that he

could wish; he doated on the boy, and found both nurse and

housekeeper in the girl. Unfortunately, his own property

was entailed on a distant relation; and this cousin installing

himself in the house within a month of the old gentleman's

sudden death, Mr and Miss Crawford were obliged to

look for another home without delay, Mr Crawford's own

house being too small for their joint comfort, and one to

which his sister had taken a fixed dislike, for reasons of her

own. Having been forced by want of fortune to go into a

profession, Mr Crawford had begun with the law, but soon

after had discovered a genius for improvement that gave him

the excuse he had been wanting to give up his first choice

and enter upon another. For the last three years he had

spent nine months in every twelve travelling the country

from Devon-shire to Derby-shire, visiting gentlemen's

seats, and laying out their grounds, gathering at the same

time a list of noble patrons and a competent knowledge

of Views, Situations, Prospects and the principles of the

Picturesque. What would have been hardship to a more

indolent, stay-at-home man was bustle and excitement to

him. For Henry Crawford had, luckily, a great dislike to any

thing like a permanence of abode, or limitation of society;

and he boasted of spending half his life in a post-chaise,

and forming more new acquaintances in a fortnight than

most men did in a twelvemonth. But, all the same, he was

properly aware that it was his duty to provide a comfortable

home for Mary, and when the letter from the Park was

soon followed by another from the parsonage offering his

sister far more suitable accommodations than their present

lodgings could afford, he saw it as the happy intervention of

a Providence that had ever been his friend.

The measure was quite as welcome on one side as it

could be expedient on the other; for Mrs Grant, having

by this time run through all the usual resources of ladies

residing in a country parsonage without a family of children

to superintend, was very much in want of some domestic

diversion. The arrival, therefore, of her brother and sister was

highly agreeable; and Mrs Grant was delighted to receive a

young man and woman of very pleasant appearance. Henry

Crawford was decidedly handsome, with a person, height,

and air that many a nobleman might have envied, while

Mary had an elegant and graceful beauty, and a strength

of understanding that might even exceed her brother's.

This, however, she had the good sense to conceal, at least

when first introduced into polite company. Mrs Grant had

not waited her sister's arrival to look out for a desirable

match for her, and she had fixed, for want of much variety

of suitable young men in the immediate vicinity, on Tom

Bertram. He was, she was constrained to admit, but twentyone,

and perhaps an eldest son would in general be thought

too good for a girl of less than two thousand pounds, but

stranger things have happened, especially where the young

woman in question had all the accomplishments which Mrs

Grant saw in her sister. Did not Lady Bertram herself have

little more than that sum when she captivated Sir Thomas?

Mary had not been three hours in the house before Mrs

Grant told her what she had planned, concluding with,

‘And as we are invited to the Park this evening, you will see

him for yourself.'

‘And what of your poor brother?' asked Henry with a

smile. ‘Are there no Miss Bertrams to whom I can make

myself agreeable? No rich ward of Sir Thomas's I can

entertain? I ask only that they have at least twenty thousand

pounds. I cannot exert myself for any thing less.'

‘If that is your standard,' replied Mrs Grant, ‘then

Mansfield has only one young woman worthy of the name.

Fanny Price is Sir Thomas's niece, and has at least twice

that sum, and will inherit her grandfather's Cumberland

property, and some vast estates in the West Indies, I believe.

And she is generally thought to be by far the handsomest of

the young ladies—quite the belle of the neighbourhood. But

I am sorry for your sake, my dear brother, that she is already

engaged. Or at least, so I believe, for no announcement has

actually been made, but Mrs Norris told me in confidence,

that Fanny is to marry her son Edmund. He has a very

large property from his father, though you would scarcely

believe it from the way his mother carries on. Such

assiduous economy and frugality I have never known, and

certainly not from a person so admirably provided for as

Mrs Norris must be. I believe she must positively enjoy all

her ingenious contrivances, and take pleasure in saving half

a crown here and there, since there cannot possibly be any

other explanation.'

Mary heaved a small sigh at this, and thought of the

considerable retrenchment she had been forced to make in

her own expenditure of late. Mrs Grant, meanwhile, had

returned to the young ladies of the Park.

‘You will be obliged to content yourself with Miss

Bertram, Henry. She is a pretty young lady, if not so

handsome as Miss Price, and has a nice height and size, and

sweet dark eyes. But I warn you that you may encounter

some competition in that quarter. A Mr Rushworth has but

lately arrived in the neighbourhood, and I believe we may

even see him at the Park this evening. He is the younger son

of a baronet, with an estate of four or five thousand a year,

they say, and very likely more.'

Henry could not help half a smile, but he said nothing.

The dinner hour approaching, the ladies separated for

their toilette. Although Mary had laughed heartily at her

sister's picture of herself as the future mistress of Mansfield

Park, she found herself meditating upon it in the calmness

of her own room, and she dressed with more than usual

care. The loss of her home, with all its attendant indignity,

had been a painful proof that matrimony was the only

honourable provision for a well-educated young woman of

such little fortune as hers. Marriage, therefore, must be her

object, and she must resign herself to marrying as well as

she could, even if that meant submitting to an alliance with

a man of talents far inferior to her own.

As the weather was fine and the paths dry, they elected to

walk to their engagement across the park. If she could not

share her brother's professional interest in the disposition

of the grounds, Mary yet saw much to be pleased with:

lawns and plantations of the freshest green, and nearer the

house, trees and shrubberies, and a long lime walk. From

the entrance hall, they were shewn into the drawing-room,

where everyone was assembled. They soon discovered,

however, that the family had been frustrated in their hopes

of Mr Rushworth; he had sent Sir Thomas a very proper

letter of excuse, but regretted that he was required directly

in town. The immediate disappointment of the party was

rendered even more acute by the fair reports Mr Bertram

brought with him from Sotherton. In the course of the

afternoon Mr Bertram had perfected his acquaintance with

their new neighbour, and was returned with his head full of

his recently acquired friend. The topic had evidently been

already handled in the dining-parlour; it was revived in the

drawing-room, and as coffee was being poured Mary was

standing near enough to Mr Bertram for her to overhear

a discussion with her brother on the same engrossing

subject.

‘I tell you, Crawford, you never saw so complete a

man! He has taste, spirit, genius, every thing. He intends

to re-establish Sotherton as one of the foremost houses in

Northampton-shire. It has lain empty for so long, and the

house itself is sadly neglected, but Rushworth has great

hopes for it. I will take the first opportunity to introduce

you—he has above seven hundred acres, and all of it needing

as much attention as the house.'

Mr Crawford bowed his thanks. ‘I am always happy

to make the acquaintance of gentlemen of extensive and

unimproved property,' he said with a smile.

The card tables were soon placed, and Sir Thomas and

his lady, and Dr and Mrs Grant sat down to Casino. Mrs

Norris called for music, and Mary was prevailed upon by

Mr Bertram to sit down at the piano-forte. After listening

for a few minutes, Mrs Norris said loudly, ‘If Miss Crawford

had had the advantage of a proper master she might almost

have played as well as Fanny, do you not agree, Edmund?'

‘You are too kind, ma'am,' said Miss Price, colouring

most becomingly. Mr Norris said nothing, and Mary looked

up to see how warmly he assented to his lady's praise; but

neither at that moment nor at any other time during the

evening could she perceive any visible symptom of love; and

from the whole of his behaviour to Miss Price she derived

only the conviction that he was an arrogant, weak young

man, driven by motives of selfishness and worldly ambition

into a marriage without affect

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...