- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

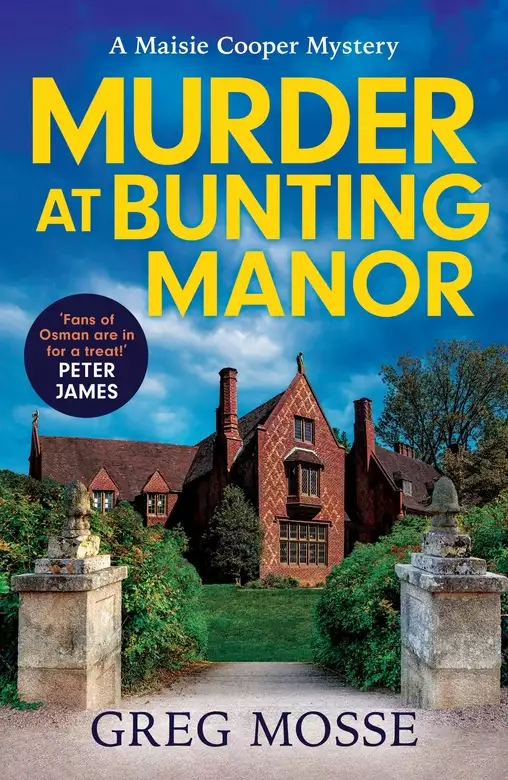

The second in the brand-new cosy crime series from Greg Mosse, featuring amateur sleuth Maisie Cooper set in the rolling Sussex countryside where crimes and murder abound...

Something is afoot in the little village of Bunting and someone is trying to kill the lady of the manor. Luckily, amateur sleuth Maisie Cooper is on the case.

Maisie Cooper is done catching murderers, thank you very much. Having recently brought her brother's killers to justice, she's ready to go back to her glamorous life in Paris. But little does she know that the idyllic Sussex countryside is home to more than one criminal...

When Maisie receives a letter asking for her help in the little village of Bunting from the lady of the manor, she is curious enough to accept. She is then shocked to discover that the very woman requesting her assistance is her estranged Aunt Phyllis, who believes that someone is out to kill her. Maisie must follow the clues to find the culprit before they strike again.

As Maisie investigates alongside handsome Sergeant Wingard, she starts to wonder...

Why would someone want Aunt Phyllis dead?

What could her eccentric aunt have possibly done to be the target for a killer?

And does Maisie quite like all this detective business after all?...

(P)2023 Hodder & Stoughton Limited

Release date: November 9, 2023

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Murder at Bunting Manor

Greg Mosse

It was a crisp autumn day on the cusp of winter, November 5th, 1971. In a village hidden in a fold of the Sussex Downs, preparations for Guy Fawkes Night were almost complete, watched by a stranger, a woman dressed in several layers of ill-assorted clothes – almost rags. She had walked to Bunting along the pilgrim way, across the hills.

The bonfire field was beside a lane that led up to an untidy failing farm. For an hour at least – she had no watch – the stranger observed the villagers stacking prunings from overgrown hedges and fallen trees. Then the publican arrived – a little unsteadily – with the ‘Guy’, a pair of old striped pyjamas crammed with straw. The village shopkeeper brought the head, an upturned paper bag stuffed with newspaper and decorated with black wool for his long stringy hair, the face drawn on with a thick felt-tip pen – dark eyes, heavy brows, an ugly mouth with blacked-out teeth. The stranger watched the shopkeeper sew the head to the pyjama collar with a darning needle. It lolled to one side, grinning foolishly in the failing sun.

Finally, a strongly built woman in a worn wax jacket drove up in a tired Land Rover with an enormous box of fireworks. Her labouring man began setting the rockets in the ground, the Catherine wheels on the fence.

Earlier, a little before ‘last orders’ for the lunchtime service, the stranger had gone to lurk at the back door of the pub, the Dancing Hare, begging for scraps. A kind young woman with wide-set eyes, clear skin and nervous hands had given her a piece of quiche left over from someone’s plate and told her she might come back at evening opening time, at five-thirty, for something else.

The gift had made the stranger feel warm inside. She had eaten it ‘out of her hand’, as the country people said, standing on the village green, watching a drab couple teaching two smallish boys – one English, one brown-skinned with dark brows – how to wash their tiny car, an off-white Hillman Imp with rust peeking through the paintwork round the wheel arches. Then, the four of them had gone back inside their ugly salmon-pink house, leaving their buckets and sponges and chamois leathers on the front step. The girl from the pub had turned up and was shouted at to ‘bring in the things’ and ‘not make another mess like this morning’.

The stranger’s cold feet were sore from her trudge over the hills, so she left the bonfire field and went to sit in the porch of the church, looking out at the gravestones. Then, after a while, looking at nothing at all.

Time passed. Day became dusk, dusk became almost night.

From a smart-looking converted worker’s cottage on the far side of the green, a red-faced overweight man, encased in a grey three-piece suit, picked his way through the puddles around the green, a sheaf of music in his hands. Seeing the stranger, he screwed up his piggy face in a sneer of contempt and went inside. Discreetly, she followed him, sitting quietly in a rear pew, almost out of sight beside a pillar, while he practised Christmas hymns at the organ.

Soon she heard footsteps and there was the girl from the pub again, looking reluctant and unhappy.

‘At last,’ said the red-faced man, heaving himself off the organ stool and lumbering towards her. ‘What’s this I hear about you not singing the solos at Christmas, Zoe?’

‘I’m sorry, Mr Kimmings, I don’t want to.’

‘Don’t want to?’ he spat. ‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘I’m very sorry,’ said the girl.

‘You need to learn that life isn’t about what you want to do,’ he told her. ‘It’s about doing your damn duty. That’s what young people don’t understand. I’m surprised you haven’t a better sense of your obligations. What are you? An orphan with no family, living off the kindness of Mr and Mrs Beck, off the kindness of the state.’

‘Yes, Mr Kimmings.’

‘I’ll thank you to give me my rank and call me “Commander”. Someone should take a slipper to you, you little minx.’

‘In school,’ said the girl, truculently, ‘they tell us it’s rude to call people names.’

Quick as a flash, he lurched forward and slapped the girl’s face with the flat of his meaty hand. The stranger stood up in her pew. The girl ran towards the door. Just then the vicar – a tall man with a bland unremarkable face – stepped inside, catching her in his arms, clutching her to his chest.

‘Now, what’s the matter?’ he asked, his eyes wide.

The girl pulled away, taking a couple of stumbling steps.

‘Stop it. I hate you. I hate you both.’

She sounded like a small, broken child. The stranger wanted to say something to comfort her, but she didn’t have time, because the girl ran away and the two men disappeared into the vestry.

The stranger shuffled outside. A hundred yards away, she could see the girl disappearing into the Dancing Hare. The church bell chimed and a car pulled in – a Triumph Herald. Its occupants came tumbling out, a happy family looking forward to the fireworks but keen to get into the pub nice and early for their quiche or ‘fish-in-a-basket’ beforehand.

The stranger made her way to the back door and stood in a corner, away from the lighted rear window, through which she could see children with parents who loved them, a wife who respected her husband, a husband devoted to his wife. At least, that was how it seemed.

She wondered if the girl would remember her promise, but soon the door opened and the pale face looked out.

‘Are you there?’

‘I’m here,’ said the stranger, her words only just louder than the breeze.

The girl stepped outside. The slice of quiche was warm in her hands, steam rising in the chilly air.

‘If you want, there’s room to sit down in the woodshed.’

‘No one will be coming out for logs, then?’

‘We’ll not be needing any more. We shut early to go up to the bonfire and the fireworks. You should stay for the display.’

The girl went back inside and the stranger did as she suggested, perching on a heap of cut beechwood in the log shelter, pulling her rags around her for warmth.

Maybe I will stop on, she thought. There’s no one who’ll miss me.

Once she had finished eating, wiping her oily fingers on her clothes, the stranger crossed the road and took the path through the woods towards the untidy gravel drive of Bunting Manor. From the shadow of the encroaching trees, she paused to peer in through tall leaded windows, seeing the firework woman in the worn wax jacket, opening a trapdoor in the floorboards. She descended to her basement, returning a few moments later with a dusty bottle of wine.

The stranger moved on. At the corner of the building, a cold moon revealed steps that led down to the outside door of the wine cellar, half concealed by overhanging leaves.

That might be useful, thought the stranger, when I come back.

ONE

It was ten in the morning on a bright and blue-skied Saturday at the beginning of March, 1972. A week had gone by since Maisie Cooper had solved the puzzle of her brother Stephen’s murder. The grief and the loss were still raw. With distressing frequency, memories of all she had seen and learnt came unbidden into her mind, robbing her of sleep, unsettling her days. She was tormented by regret that she hadn’t been present enough in Stephen’s life to save him from his cruel fate. She felt sickened by all she had discovered about human depravity. She tried to hold on to her sense of satisfaction at having solved the puzzle – the idea that she had, at least, been an agent of justice.

Yes, she had solved the mystery of his murder at a cost of turning her own life upside down.

Feeling rather sluggish, Maisie dressed in the cold bathroom of Church Lodge, brushing her teeth with pink Eucryl tooth powder, running damp fingers through her short curly hair. Downstairs, in the kitchen, she found the Aga was still slightly warm from the previous evening. She had sat up late with Jack Wingard, a sergeant in the Chichester police, talking over old times and, at rather depressing length, the trials that she would soon be obliged to attend.

‘You’ll be a crucial witness,’ he had reminded her.

‘I know that,’ she had replied, more snappishly than she meant. ‘Do you think I’ll be criticised for interfering in the investigation?’

‘I wouldn’t be surprised,’ Jack had replied, sympathetically. ‘You may have “invited censure”.’

That had made Maisie cross and put a dampener on things, despite both of them trying not to let it. Maisie had tried to lighten the mood with memories of their shared school days. Finally, Jack had left, driving away in his white Zephyr police car, a look of frustrated regret in his lovely warm eyes.

I wonder, thought Maisie, if we’ll ever get past this.

Maisie stoked the fire box of the Aga with a good shake of coke from the scuttle, leaving the cast-iron door ajar to draw new flame. She felt conflicted, unable to accept Jack’s declarations of affection – of love? – but aware that she was deeply drawn to him as well.

She made herself a cup of double-strength instant Maxwell House coffee, improving it with gold-top milk and demerara sugar, and drank it sitting on a tea towel on the back step, looking out at the orchard garden.

She would soon have to leave her late brother’s rented home. She had been given a week’s dispensation to stay on by the owner, but that was now over. Her open return ticket for the boat train to Paris was in her handbag. If she left that very night, she could wake the next morning at the Gare du Nord and take the métro to her shabby apartment under the mansard roof of a building on the Place des Vosges. Then, back to work in her role as a high-class tour guide. Were it not for the preparations for the trial, she might already have left.

Were it not for Jack, too.

Maisie drained her cup and went back inside. The Aga had drawn up nicely and the room was beginning to warm up. On the table was a copy of the local newspaper. On the front page was a drawing of the celebrated Tudor prayer book, stolen from Chichester cathedral crypt and central to her investigation of Stephen’s death.

Maisie shut the firebox and set about the task she had allotted herself – cleaning and dusting the large cold house, determined to leave it better than she found it. She worked for almost two hours: Duraglit wadding on the brass door handles; Vim cleaning powder on the porcelain in the bathroom and kitchen; Vigor liquid on the chequerboard hallway floor. As the nearby church clock chimed twelve, still she hadn’t attacked the cobwebs high in the double-height ceiling.

She decided to give herself a break and opened the front door. The sky was a limpid blue. Birds were singing in the trees. Last year’s fallen leaves, blackened to mulch, smothered the untidy borders, but snowdrops and dwarf narcissi were poking through, like upright green swords. A rabbit came lolloping out from under the evergreen choisya, sniffed the air, looked left and right, then disappeared beneath the dark, waxy leaves of the rhododendron.

‘Well, Maisie,’ she told herself out loud. ‘I think it’s time.’

She put on an old quilted anorak she had found hanging in the hall and went outside, walking briskly, crossing the road to the small car park in front of the pub, the Fox-in-Flight. She paused to look in and was surprised to see Maurice Ryan, her late brother’s solicitor, sitting in the window with a young woman wearing a rather ratty Afghan coat. They seemed to be discussing something private. The girl kept glancing round the bar to make sure they weren’t overheard.

If that’s a client, thought Maisie, I wonder what sort of legal advice she can possibly be seeking.

She walked on, past the blacksmith’s forge then along a right turn leading to an uninspiring red-brick close, a small U-shaped council estate of eighteen cheap houses surrounding a tatty green. A girl of about fourteen years old was sitting on the solitary bench, her left hand gently moving a pram back and forth. Maisie made her way to the last house on the left, apparently identical to all the others but, for her, imbued with special memories.

For the two weeks she had been back in Framlington, Maisie had avoided even looking at her old family home. It was here that she and Stephen had been raised by loving parents. It was here that she had first tasted tobacco and found the taste disgusting and the after-effects depressing. It was here that she had first made herself sick with alcohol – a particularly ripe local apple scrumpy – and her father Eric had sat with her until she had managed to drink a pint of cold water, then let her sink into grateful sleep. It was also here that her mother Irene had taught her and Stephen their first useful words of French, kick-starting their love of languages.

But those loving parents had died a decade before, in a road-traffic accident in one of the last London pea-souper fogs. And now Stephen was gone, too, and she was alone.

What did looking at the house make her feel? Nothing much. It was just a rather mean council house where some unknown new people were pleased or disappointed to live.

A curtain twitched in an upper window and Maisie turned away, not wanting to have to explain herself, trying not to feel disappointed. There was one other place she couldn’t fail to find her parents. For the first time in ten years, she would look at Eric and Irene’s shared resting place – a memorial she had avoided for the grief it would undoubtedly cause her to feel.

For a minute or two, in the graveyard at the end of Church Lane, she was frustrated, unable to locate their stone. She felt a kind of panic that it had been removed for some reason, as a kind of punishment.

Why a ‘punishment’? Because she had paid it no attention and because the unconscious mind is a harsh judge.

Yes, she had been miles away in the West Country when they had been run over by a London bus. No, their deaths had been nothing but a stupid accident. But they were dead and she was alive. And, now, Stephen was dead as well, burnt to ashes at the dismal Chichester crematorium.

That was the problem. Stephen and Eric and Irene were gone while she still lived. And what was she going to do with her life, with all of its myriad possibilities? What did she want – the hustle and excitement of Paris or the reassurance of rural Sussex?

And Jack.

At last, she found the grave, beyond the yew tree on the southern edge of the graveyard, a modest upright stone in black basalt. She read the confident inscription, the words seeming hollow, though she knew they were well meant.

Eric and Irene Cooper, their love will endure.

It wasn’t fair. Why had they been taken? The world was full of people who didn’t deserve to live, but Eric and Irene were not among them.

She sighed.

‘It’s not fair,’ she said aloud.

She left the graveyard and trudged back up Church Lane, barely lifting her feet. She saw Maurice Ryan go past in his rather ostentatious bottle-green Rover car, driving back into town. When she turned in at the drive of Church Lodge, she was delighted to find Jack waiting for her, off duty, looking immensely handsome in jodhpurs and tweed hacking jacket. He smiled and she smiled back.

They didn’t kiss or even touch one another – there had been just one moment during the investigation into the murder at Church Lodge when he had taken her in his arms, relieved to know she was safe, angry that she had walked into danger – but the next two hours passed in a blur of laughter at the stables and up across the gallops on the Downs, by turns breathless and delighted. When, at last, their horses were tired, they walked them back to the yard and brushed them down in companionable silence, helped by Bert Close, the elderly stable lad.

Once they had finished, Jack asked Maisie what else she had to do, then added, with sadness in his lovely warm eyes: ‘Before you leave for Paris?’

‘I haven’t gone yet,’ she told him. ‘Oh, and Charity asked me to drop in.’

Charity Clement was wife and assistant to Maurice Ryan, Stephen’s solicitor.

‘I’ll give you a lift. I have a surprise for you, too.’

‘You do?’

‘It will give you a kind of resolution, I hope,’ he told her.

Maisie wondered what it could possibly be.

‘Are you sure I’ll like it?’ she asked.

‘I believe you might,’ said Jack, in his steady way.

‘Then, yes,’ said Maisie, lightly. ‘I accept your kind offer of a lift.’

TWO

Back at Church Lodge, Maisie felt a frisson of unaccustomed intimacy as she washed and changed upstairs in her bathroom, knowing that Jack was doing the same in the warm kitchen. When she came down, flushed and smiling, she felt embarrassed to find him waiting by the door, looking adoringly up at her.

‘So, what’s next?’ she asked.

‘You’ll see,’ he said with a wink. ‘And don’t forget, Grandma is expecting you for dinner this evening.’

That, too, would be a new level of entanglement of their lives. Would she welcome it? Yes, she would.

They drove into Chichester, across a stretch of arable land then through the woods. Everywhere Maisie saw evidence of quickening new life – buds beginning to open on the trees, early lambs in a field, daffodils on the verges.

Jack parked outside the cathedral and led her to the impressive west door. They went inside.

‘Why are we here?’ Maisie asked.

‘I hope this is the right thing to do,’ he told her, frowning. ‘I thought it might help to lay a few ghosts to rest.’

‘I don’t understand.’

Jack seemed unusually tentative.

‘I’m sorry if it turns out to be a mistake.’

Maisie wondered what it could be.

‘We’re here, now,’ she told him. ‘Why don’t you just tell me?’

At that moment, they were joined by a small man in a dusty shapeless suit, carrying a leather-bound ledger. Maisie had briefly met him once before. He was the cathedral’s curator of historic objects.

‘Er, good afternoon, Sergeant Wingard, Miss Cooper. All is ready. Would you follow me?’ The curator led them to a flight of narrow stone stairs in the north transept of the cathedral. They followed him down. ‘A modest ceremony of rededication,’ said the curator, ‘will be conducted tomorrow lunchtime after the sung eucharist, but Sergeant Wingard has prevailed upon me to grant a private preview. Here we are.’

The curator unlocked a heavy wooden door and led them into the crypt, a surprisingly roomy space comprising several chambers, each with its own vaulted ceiling. Jack was hanging back but Maisie was drawn to the centrepiece of the well-lit display – an ancient devotional book, resting on a velvet cushion, open at the illuminated page for Justice.

‘Would you put on these gloves, Miss Cooper?’ He offered her a pair in white cotton. ‘I will leave you for a few minutes. Will you excuse me?’

He bustled away to a far corner of the crypt as Maisie stepped up to the cushioned lectern, a flutter of anxiety in her chest. She reached out a gloved hand and touched the thick pages.

‘I thought you should be able to see it properly,’ said Jack quietly. ‘I hope I did the right thing.’

Maisie wondered if the fact that it was open at the page for Justice might have been deliberate. She turned the pages, finding the other virtues depicted with skill and respect: Patience, Temperance, Hope, Charity, Faith and Courage.

‘You were right,’ Maisie replied, matching Jack’s low voice. ‘I’m glad to see it back in its rightful place.’

Jack came close, standing just behind her. He reached out a hand and placed it gently over her own.

‘Please don’t go,’ he murmured.

‘I can’t . . .’ Maisie began.

She wasn’t sure what she wanted to say, how she wanted to finish her sentence. Time slowed and her mind became almost blank. All she knew was that she didn’t want this moment to end. But, at the same time, she felt an awful ache of loneliness and loss. Would Jack’s affection always be tainted by her grief?

‘I don’t know what to—’

‘Now, er, I am a little pressed for time,’ interrupted the dusty curator and Jack snatched his hand away. ‘Perhaps you would like to attend the rededication tomorrow?’

‘No, thank you,’ said Maisie quickly. ‘I’m very grateful for your time, today.’

She gave him a bright but, she felt, brittle smile and climbed back up the narrow flight of stone steps, emerging with relief into the huge nave of the cathedral. She led Jack out through the west door and turned her face up to the weak March sun, closing her eyes, breathing deeply.

‘It was a stupid thing to do,’ Jack told her, a deep frown creasing his regular features. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘No, it wasn’t,’ said Maisie. ‘I think it will help, you know.’

‘Do you really believe that?’

Maisie sighed. ‘I hope so, Jack. I honestly do.’

‘Good,’ he said with relief. ‘Now, when I say “dinner”, I mean tea. Grandma eats at five-thirty, like the farmer’s daughter she is.’

‘I’m looking forward to it.’

‘She’s a character. I do hope you get on. And she’s interesting, too. You know she was born at the beginning of the century, in 1903?’

‘I’ll be there, Jack. Don’t worry. You get on with catching criminals.’

‘All right.’

He smiled and turned away and Maisie knew that his presence was central to how warmly she felt towards this provincial market town with its overblown cathedral and carefully cultivated history. As she watched him go, she was grateful that he had the good manners not to look back and see her gazing after him.

Once Jack had gone, Maisie took out her purse and counted her money – a few pound notes and a handful of coins. If her Paris flatmate, Sophie, hadn’t been very kind and sent her some traveller’s cheques in the post, she would have been down to her last ha’penny.

She put the purse away, gave herself a shake and walked the short distance round the corner onto West Street to Maurice Ryan’s solicitor’s office. Both Maurice and Charity were there, despite the fact it was a Saturday, doing some decorating. Maisie felt a little guilty. It was she who had pointed out how scruffy the place looked when she had visited to go through her brother’s papers.

‘Don’t feel bad, Maisie,’ said Maurice, a delicate fitch brush in his hand for painting the narrow mullions of the sash windows. ‘If I’m going to sell the business, this can only help. You know my dream is to retire to the sun.’

‘You should go, Maurice,’ said Charity to her husband. ‘You’ll be late.’

‘God, yes, I will,’ said Maurice in his flamboyant way, leaving the fitch on a piece of newspaper and casting around for the keys to his Rover. ‘No peace for the wicked.’

The keys were on the corner of Charity’s desk. He snatched them up and left.

‘What’s Maurice up to?’ Maisie asked.

‘Nine holes of golf with a client.’ Charity smiled. ‘He will lose very gracefully.’

Maisie wondered whether she should ask her friend what Maurice had been doing at the Fox-in-Flight with the girl in the Afghan coat, but Charity continued, a look of concern in her eyes, speaking French, faintly accented from her childhood in Guadeloupe.

‘Tu as beaucoup encaissé, ces derniers temps. Tu dois prendre soin de toi.’

You’ve had a lot to put up with recently. You need to look after yourself.

‘You’re right,’ Maisie told her. ‘But I feel fine. And I’m very grateful to you and to Maurice for all you have done. Do we have a date for the trial?’

‘No, not yet. But I had a message for you, something quite unexpected. I sent it on to Church Lodge in the week and now the lady has rung to say she has had no reply.’

Maisie felt guilty. She had neglected to open her post for fear of finding more of Stephen’s bills that she couldn’t afford to pay.

‘What’s it about?’

‘I’m not exactly sure,’ said Charity, with a frown. ‘Her name is Phyllis Pascal. She wants to meet you so that you can conduct an investigation on her behalf.’

‘She does?’ asked Maisie, surprised.

‘She promises “generous remuneration”,’ said Charity, encouragingly.

‘Well, that wouldn’t go amiss. Do we know why she was in touch – a stranger, appealing out of the blue on the strength of . . . Well, on the strength of what, exactly?’

‘I suppose that will form part of your discussions,’ said Charity. ‘She is a powerful woman, in her way.’

‘Powerful how?’

‘How is any woman powerful? She has money. She is connected to several of Maurice’s most important clients. And your brother’s murder was widely reported, not just in the local papers but in the nationals, too. She says she read about it and learnt of the role that you played in uncovering the facts.’

Maisie felt pride in her achievement but was private enough to hate being ‘talked about’.

‘Jack and I agreed that we should play that down.’

‘Sergeant Wingard was not the source of the . . . What is the English word?’

‘The leak?’

‘That’s it, although you must remember, Maisie, these things are a matter of public record.’

‘All the same, someone must have spoken to a journalist.’ An idea came into her mind. ‘You remember Police Constable Goodbody? Barry Goodbody, the one who looks like a ferret?’

‘A ferret?’

‘Un furet.’

‘Oh, yes, he does.’ Charity laughed and the sound was a delightful counterpoint to Maisie’s rather sombre mood. ‘An angry ferret.’

‘He hated me from the very first,’ said Maisie.

‘Because you conducted your own freelance investigation in parallel to the police,’ said Charity, reasonably. ‘Anyway, it. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...