- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Mirabelle Daws travelled all the way from Australia to Sheridan Square to visit her sister — only to die in the middle of a locked garden. All the residents of Sheridan Square have a key to the garden — but no-one seemed to know that Mirabelle was planning to arrive.

So the question facing Mrs. Jeffries and Inspector Witherspoon is: who wanted to make sure that Mirabelle's visit was very, very short-lived?

Release date: September 1, 1999

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 160

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

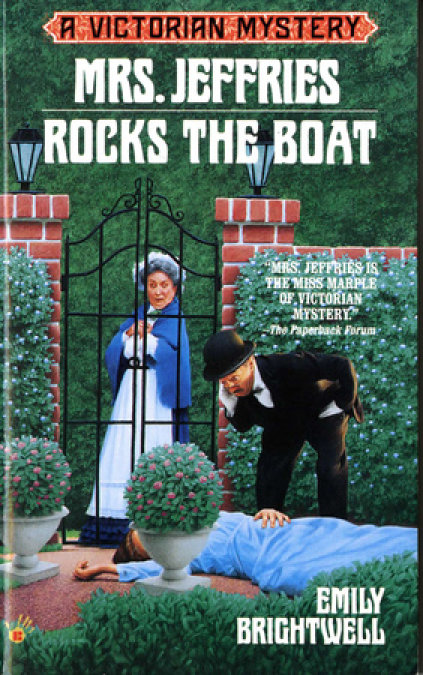

Mrs. Jeffries Rocks the Boat

Emily Brightwell

ROCKS THE BOAT

CHAPTER 1

Malcolm Tavistock unlocked the heavy, spiked gate and pushed it open. “Come along, Hector,” he said, yanking gently on the bulldog’s lead. Hector, with one last sniff at an errant dandelion that had poked up between the stone squares of the footpath, followed his master.

“Humph,” Tavistock glared at the dandelion as he and the dog stepped into the gated garden in the middle of Sheridan Square. He made a mental note to have a word with the gardener. The place certainly looked scruffy. He pulled the gate shut behind him and made sure he heard the lock engage before carefully pocketing the key.

Sheridan Square was for residents only. It wasn’t a public garden and Malcolm, for his part, would do his best to insure it never became one. It rather annoyed him that some of his other neighbors on the square weren’t as diligent as he was about insuring the security of the garden. Tugging at the dog’s lead, Tavistock strolled up the footpath toward the center of the large square, his eagle eye on the lookout for more signs of neglect on the part of the gardener. The animal trudged along next to his master, keeping his nose close to the ground and sniffing happily at the bits of grass and clumps of leaves.

Suddenly, Hector came to a dead stop and his thick white head shot up. He sniffed the air and then lunged up the path, yanking his master along behind him.

“Hold on, old fellow,” Malcolm ordered as he pulled back on the lead. He wasn’t through ascertaining exactly how much of a tongue-lashing to give that wretched gardener. “Humph,” he sniffed as he surveyed the area. The place was abysmal. The bushes along the perimeter had grown high and unwieldy. The footpath was scattered with stems and leaves and bits of dried grass, the flower beds were filled with weeds, and the lilac bushes were completely overgrown. “Well, really,” Malcolm muttered. “Am I the only one that cares how this garden looks? The garden committee shall certainly hear about this.”

Hector lunged again, almost yanking Malcolm off his feet.

“Oh, all right.” Malcolm finally decided to let the poor dog have his walkies. He looked around, saw that he was the only one in the garden, and then dropped the lead. “Go on, boy. I’ll catch up in a moment.” Hector took off like a shot. Malcolm reached down and picked up a dirty bit of paper that was littering the path. “Honestly,” he muttered as he crumpled the paper into a tight ball, “some people have no consideration for others.”

From the center of the square, Hector howled.

Malcom was so startled, he jumped. He stuffed the paper in his pocket and ran towards his dog. His heart pounded against his chest. For all his grumbling, he loved that silly dog, and Hector might look like a terror, but he was easily upset.

Flying up the path, Malcolm skidded to a halt. Hector was perfectly all right. He was standing next to a bench upon which a woman lay stretched out sound asleep.

“Well, really,” he exclaimed. “What has become of this neighborhood! Hector, come away from that disreputable person immediately.” This wasn’t the first time such a thing had happened. Because the garden was shielded by the high foliage from the eyes of passing policemen, vagrants occasionally climbed the fence. But this was the first time Malcolm had ever seen a woman do it. “What is the world coming to?” Malcolm muttered. He marched toward the bench. “I blame those silly suffragettes,” he told Hector. “Puts stupid ideas in women’s heads.” He bent over the sleeping woman, frowning as he realized her clothes were new and expensive. Not the sort of clothes a vagrant would wear. He was suddenly a bit cautious. “Uh, miss.” He poked her gently in the arm. “Is everything all right?”

The woman lay silent.

Hector whined softly.

Frightened now, Malcolm looked around him at his surroundings and wished he were visible from the street. The hair on the back of his neck stood up, and he shivered. But he couldn’t just leave the woman lying here. “Miss,” he said loudly, “are you all right?”

Hector whined again and stuck his nose under the wooden slats. But his head wouldn’t go in very far as the lead had got tangled around the base of the gas lamp next to the bench. Malcolm bent down and untangled the lead; as he stood up, he saw what was under the bench. Stunned, he blinked and then forced himself to look again. But the view didn’t change. In the pale morning light it was easy to see exactly what it was. Blood. Lots of it. Grabbing the dog’s lead, he pulled him hard toward the gate. “Come on, Hector, we’ve got to find a policeman. That poor woman’s dead. There’s blood everywhere.”

Hepzibah Jeffries, housekeeper to Inspector Gerald Witherspoon of Scotland Yard, stepped into the kitchen and surveyed her kingdom with amusement. Wiggins, the apple-cheeked young footman, sat at the kitchen table. Beside him sat a scruffy young street arab named Jeremy Blevins. In front of them was an open book, a pencil and a large sheet of paper. At the far end of the long table, Betsy, the blond-haired maid, sat polishing silver. Mrs. Goodge, the gray-haired, portly cook stood at the kitchen sink scrubbing vegetables for the evening stew.

The only one missing was Smythe, the coachman. But as it was almost morning teatime, Mrs. Jeffries expected him in any minute.

“Shall I make the tea?” Mrs. Jeffries asked the cook as she came on into the kitchen.

“No need.” Mrs. Goodge jerked her chin to her left, toward a linen-covered tray that rested on the counter. “It’s all done. But if you could just put the kettle on to boil, I’d be obliged. My hands are wet.”

“Certainly.” The housekeeper did as she was asked.

“Come on now, Jeremy,” Wiggins said to the lad, “Concentrate. You know what that letter is. You learned it yesterday.”

“I am concentratin’,” the boy shot back. “But it’s bloomin’ hard to remember every little thing.” His thin face scrunched as he stared at the book. “Uh, it’s a ‘C,’ right?”

“It’s a ‘G,’” Wiggins corrected. “Can’t you remember?”

“Leave off, Wiggins,” Betsy interjected. “Jeremy’s doing well. He’s learned ever so much in just a few days.”

“Ta, miss.” Jeremy beamed at Betsy. “I reckon I’ve done well too…mind you, I don’t know why I’m botherin’ with book learnin’. It’s not like the likes of me’ll ever get a chance to use it much.”

“You don’t want to be ignorant all yer life, do ya?” Wiggins cuffed the lad gently on the arm and closed the book. “Besides, you never know what the future holds. At least if you know your letters and can read a bit, you’ll be able to sign your own name.”

“Fat lot of good that’ll do me,” Jeremy grumbled. He’d only told this lot he wanted to learn to read as a means of getting into the house and having a bite of food every now and again. He’d not expected they’d take him at his word and whip out this silly book every time he came around because his belly was touching his backbone. Still, Jeremy mused, they were a decent lot. Treated him well, even if they did expect him to learn his bleedin’ letters. He glanced at the covered tray and wondered what sort of goodies were under the linen. He’d already been fed, but it never hurt to get some extra. When you lived like he did, you never knew when you might next eat. “Are ya havin’ a fancy tea, then?”

“No,” Betsy replied. She tossed her polishing cloth to one side and stood up. “Just our usual. Why? Are you still hungry?” Having been raised in one of the poorest slums of London, she was well aware of what the lad was up to. She’d lived on the streets for a time herself and knew what it was like to try and survive. “Help yourself to some more buns if you’re still feeling peckish. There’s plenty in the larder.” She lifted the heavy tray of silver and started for the pantry.

Surprised, Jeremy gaped at her and then quickly scrambled to his feet. He didn’t bother to look at the others; he simply followed Betsy down the hallway. He’d known as soon as he asked the question that he should have kept his mouth shut. When people were doling out charity, they didn’t like you to be greedy. He couldn’t believe she wasn’t cuffing him on the ears or giving him a lecture.

“The buns are in the dry larder,” Betsy called over her shoulder. She indicated a closed door she’d just passed and grinned as she heard it creak open behind her.

“Thanks, miss,” Jeremy called as he darted inside the larder. “I’ll ’elp meself if ya don’t mind.”

At the far end of the hall, the back door opened and a tall, dark-haired fellow with heavy features stepped inside. He took one look at the maid and frowned ominously…it was a scowl that could send strong men running for cover, but it had no effect whatsoever on Betsy. “You oughtn’t to be liftin’ that ’eavy tray.” He came forward and took it out of her hands.

“Don’t be silly, Smythe,” she replied. “It’s not at all heavy. It’s only a bit of silver.”

Smythe, the coachman, had been courting Betsy for some time now. Though they seemed quite mismatched, they were, in fact, very devoted to one another. He glanced up the hall to make sure the coast was clear and then leaned forward and snatched a quick kiss.

Jeremy chose that moment to pop out of the pantry. “I only took…” His voice trailed off as the two adults sprang apart.

Betsy whirled about, her face crimson at having been caught, even by a street lad. “Did you get some buns, then?”

Jeremy, who was almost as embarrassed as the maid, held up two of them. He’d been tempted to take more but decided against it. “I took these for me sister,” he explained honestly. “She’s only four. I’d best be off then,” he mumbled as he pushed past the couple and headed for the back door, “Tell Wiggins I’ll be back in a couple of days,” he said as he scurried out and slammed the door behind him.

“I do think we embarrassed the boy.” Smythe’s voice was amused.

“You shouldn’t have kissed me,” Betsy hissed. “He’ll tell Wiggins, you know.”

Smythe only grinned. The entire household knew that he and Betsy were sweethearts. Knew and approved. But unfortunately, their courtship kept getting interrupted by the inspector’s murder cases. “Help me take this to the pantry,” he said softly.

“You don’t need any help,” Betsy protested. She looked quickly back toward the kitchen. “The others will wonder what we’re up to.”

“The others will understand we’re doin’ a bit of courtin’,” he insisted. He started for a closed doorway opposite the wet larder.

“All right.” Betsy followed him. “What have you been doing this morning?”

He opened the pantry door and stepped inside. “After I dropped the inspector off, I took Bow and Arrow for a good run,” he replied. “They needed the exercise. Where do ya want this?”

“Put it over there.” Betsy pointed to an empty shelf on the opposite wall. The tiny butler’s pantry was too small for furniture. It consisted mainly of shelves of various sizes running up and down the length of the walls. Smythe carefully eased the tray into its place and then turned and pulled her close in a bear hug. Betsy giggled.

In the kitchen, Wiggins glanced toward the hallway. “I thought I ’eard Smythe come in.” He started to get up. “And where’s that lad got to?”

“Sit down, Wiggins,” Mrs. Jeffries ordered. “Smythe has come in, and I think he’s probably helping Betsy put the silver away. I expect that Jeremy has helped himself to some buns and left.” Unlike the footman, she knew precisely what was going on down the hallway.

“But I need to ’ave a word with Smythe.” Wiggins started to get up again. “’E promised to—”

“Sit down, boy,” Mrs. Goodge said sharply. “You’ve no need to go botherin’ Smythe now. He’ll be in for his tea in a few minutes. You can talk to him then.”

“But Betsy’s talkin’ to ’im now…” Wiggins’s voice trailed off as he realized what the two women already knew. His broad face creased in a sheepish grin. “Oh, I see what ya mean. They’re doin’ a bit of courtin’.”

“That’s none of our business.” Mrs. Goodge placed the tray of food in the center of the table. She pushed a plate of sticky buns as far away from Wiggins as possible and shoved a plate of sliced brown bread and butter in front of the boy. He ate far too many sweets. Then she put the creamer and sugar bowl next to the stack of mugs already on the table. Lastly, she put the heavy, brown teapot in front of the housekeeper and then shoved the empty tray onto the counter behind her.

Mrs. Jeffries smiled her thanks and began pouring out the tea. She’d done a lot of thinking about Betsy and Smythe. They were, of course, perfect for one another. She certainly hoped that Smythe would ask the girl to marry him. She wasn’t foolish enough to think a change of that significance wouldn’t have an effect on the household. It would. A profound effect.

To begin with, she wondered if the two of them would want to stay on in the household if they married. Normally, a maid and a coachman who wed would simply move into their own room and stay on. But these weren’t normal circumstances. Smythe would want to give his bride her own home. A home she suspected he could well afford. The housekeeper was fairly certain that one of the main reasons he’d not yet proposed was because he couldn’t think of a way to tell the lass the truth about himself. But that wasn’t what was worrying the housekeeper. Smythe could deal with that in his own good time. What concerned her was what would happen to their investigations if Smythe and Betsy married and moved out.

She sighed inwardly. There was nothing constant but change in life, she thought. When she’d come here a few years back, she’d never thought she and the others would get so involved in investigating murders. But they had. They’d done a rather good job of it as well, she thought proudly. Not that their dear inspector suspected they were the reason behind his success as Scotland Yard’s most brilliant detective. Oh dear, no, that would never do.

Mrs. Jeffries put the heavy pot down. They’d come together and formed a formidable team. The household, along with their friends Luty Belle Crookshank and her butler Hatchet had investigated one heinous crime after another. Those investigations had brought a group of lonely people closer to one another. In their own way, they’d become a family. Now they had to make some adjustments. Murder, as interesting as it was, couldn’t compete with true love. Especially, she told herself, when they didn’t even have one to investigate. Not that she was thinking that someone ought to die just so she and the rest of the staff could indulge themselves. Goodness, no, that would never do. Murder was a terrible, terrible crime. It was impossible to think otherwise.

Still, if someone did die, she thought wistfully, it would break the monotony of the household routine and give all of them a much-needed bit of excitement. She shook herself when she realized where her thoughts were taking her. Then she looked up and found the cook gazing at her with an amused expression on her face. There were moments, Mrs. Jeffries thought, when she was sure Mrs. Goodge could read her mind.

“Mr. Tavistock, if you’ll just tell us how you came to find the body, please,” Inspector Gerald Witherspoon said gently to the portly, well-dressed gentleman.

“Yes, I will, just give me a moment, please.” He swallowed and glanced down at the fat bulldog that sat at his feet, seeming to take strength in the animal’s presence. He lifted his head and ran a hand nervously through his wispy gray hair. His blue eyes were as big as saucers, and his elderly face was pale with shock.

Inspector Witherspoon, a middle-aged man with thinning dark hair, a fine-boned, pale face and a mustache, smiled kindly at the witness he was trying to interview. The poor fellow was so rattled, the hands holding the dog’s lead trembled. Witherspoon didn’t fault the man for being upset. Finding a corpse generally had that effect on people. To be perfectly frank, it still rattled him quite a bit.

“I’ve already told those constables.” Tavistock pointed a shaky finger at two uniformed police guarding the bench on which the body still lay. “I don’t think I ought to have to tell it again. It’s most upsetting.”

“I’m sure it is, sir,” the inspector replied. He glanced at the policeman standing next to Tavistock. Constable Barnes, an older, craggy-faced, gray-haired veteran who worked with Witherspoon exclusively, stared impassively out at the scene.

“Constable,” Witherspoon said, “have one of the lads take Mr. Tavistock home. We’ll have a look at the body and then pop over and take his statement when we’re finished.”

Tavistock slumped in relief. “Thank you, Inspector. I live just across the Square.” He pointed to a large, pale gray home on the far side. “I don’t mind admitting I could do with a cup of tea.”

Barnes signaled to a uniformed lad, and a few moments later the witness, with his dog in tow, was escorted home. Witherspoon stiffened his spine and started up the footpath toward the body. He’d put off actually having to see it till the last possible moment. But he knew his duty. Distasteful as it was, he’d look at the victim.

He simply hoped it wasn’t going to be too awful.

“She’s right here, sir,” the PC standing guard called out as soon as he spotted the inspector. “We did just like Constable Barnes instructed, we didn’t touch anything.”

“Good lad.” Witherspoon swallowed heavily. He stopped next to the bench and looked down at the victim.

“She’s not all that young,” Barnes murmured. He’d come back to stand at the inspector’s elbow. “And her clothes don’t appear to be tampered with.”

“True,” Witherspoon replied. The victim was a middle-aged woman with dark brown hair peeking out of her sensible cloth bonnet. The hat skewed to the side revealed a few strands of gray at her temples. She wore a deep blue traveling dress with expensive gold buttons. Her feet, shod in black high button shoes, dangled off the end of the bench. “She’s tall,” Witherspoon muttered. “That bench is over five and a half feet long.” For a moment, he forgot his squeamishness. Except for the blood pooling underneath the bench she could almost be asleep. Her skin hadn’t taken on that hideous milk blue color he’d seen in other corpses. He rather suspected that meant she’d not been dead long.

“She’s not got any rings on sir.” Barnes pointed to her hands, both of which were splayed out to one side of the body. “So unless the killer stole them, I think we can assume she’s not married.”

“But the killer may very well have stolen her jewelry,” the inspector said. “As you can see, she’s not got a purse or a reticule with her. Not unless it’s underneath the body.”

Taking a deep breath, he squatted down next to her. Barnes did the same. “Let’s turn her over,” Witherspoon instructed. Gently, the two men turned her on her side. The inspector winced. “She’s been stabbed. I rather thought that might be the case.”

“Poor woman.” Barnes shook his head in disgust. “And from the looks of that wound, it weren’t a clean, quick kill either.”

Witherspoon forced himself to examine the wounds more closely. The constable was right, the woman’s dress was in ribbons, and it was obvious, even to his untrained eye, that she’d been stabbed several times before she died.

“How many times do you reckon?” Barnes asked.

“It’s impossible to tell. The police surgeon ought to be able to give us an answer after he’s done the post mortem.”

“She might have screamed some,” Barnes said grimly. “As it looks like the first thrust didn’t kill her, maybe someone heard something.”

“Let’s hope so,” Witherspoon mumbled. “But I don’t have much hope for that. There’s a constable less than a quarter mile from here. Why didn’t someone go get him if they heard a woman screaming?”

Barnes shrugged. “You know how folks are, sir. Lots of them don’t want to get involved.”

Together, they gently lowered the body back down. Witherspoon stared at the poor woman and offered a silent prayer for her. There was nothing more they could learn from her. She’d gone to her final rest in the most heinous, awful manner possible. Now it was up to him to see that her killer was brought to justice.

Witherspoon cared passionately about justice.

“There’s nothing on her to identify her, sir.” Barnes stated. He stood up. “Nothing in her pockets and no purse or muff.”

“Hmmm.” The inspector frowned heavily. “We must find out who she is. Let’s give the garden a good search. There may be a clue here. You know what I always say, Barnes, even the most clever of murderers leaves something behind.”

Barnes blinked in surprise. He’d never heard the inspector say anything of the sort. “Right, sir.”

“We’d best send a lad back to the station to see if there are reports of any missing persons matching the victim’s description.”

“Right, sir.”

“And I suppose I ought to send a message home”—Witherspoon stroked his chin thoughtfully—“and let them know I’m probably going to be late.” Drat. Tonight he’d planned on sitting in the communal gardens with Lady Cannonberry, his neighbor. But duty, unfortunately, must come before pleasure. “You’d better let your good wife know as well, Constable. Can’t have people worrying about us when we’re late for supper.”

“I’ll take care of it, sir.” Barnes replied with a grateful smile. He was touched by Witherspoon’s thoughtfulness. His good wife would worry if he was late.

They spent the next half an hour searching the area, but even with the help of five additional policemen, they found nothing in the square that gave them any indication of who their victim might be.

When the body had been readied for transport to the morgue, Witherspoon and Barnes followed it out to the street. They left two constables inside to guard the area and also to keep an eye out for who came and went in this garden.

The attendants loaded her into the van and trundled off. Witherspoon turned to his constable. “Right, we’ve a murder to solve, then. Let’s get cracking. Send some lads around on a house to house to see if anyone heard or saw anything.” His gaze swept the area. “I daresay, this is quite a nice area.”

“Very posh, sir,” Barnes replied. “And the garden is private, sir. That ought to make it easier.” He pointed to the gate. “You need a key to get inside. But there wasn’t a key on the victim, so that means she either knew her killer and came in with him or her, or the gate was already unlocked when she got here.”

“I suppose she could have scaled the fence,” Witherspoon muttered. He looked at the high, six-foot spiked railings and then shook his head. “No, that’s not likely. Not a woman of that age.”

Barnes smiled. “I agree, sir. I can’t see her leaping the ruddy thing.”

“I suppose she could have had a key and the killer took it with him after he’d stabbed her,” Witherspoon said thoughtfully.

“The only people with keys are residents of the square,” Barnes said. “Malcolm Tavistock said he’d never laid eyes on the woman before and he ought to know. He’s lived here for years.”

“Who?”

“Tavistock,” Barnes replied. “The man who found her.”

“Ah yes.” Witherspoon nodded sympathetically. “Poor fellow. Finding a body isn’t a very nice way to start one’s day.”

“Neither is getting stabbed.”

“Right,” Witherspoon sighed. Sometimes he felt a bit inadequate for the task at hand. But then again, he’d try his very best. “Let’s get on with it. Where does Mr. Tavistock live?”

“This way, sir.”

The Tavistock house was directly across from the entrance to the garden. Like its neighbors, the dwelling was a pale gray, three-story townhouse with a freshly painted white front door. The inspector banged the shiny gold knocker, and almost instantly Malcolm Tavistock stuck his head out. “I suppose you want to come in?” he said grudgingly.

Witherspoon didn’t take offense at the man’s words. “That would be helpful, sir,” he replied. He was inclined to give the poor fellow the benefit of the doubt. The shock of stumbling across a body could make someone behave in the most appallingly rude way.

Tavistock gestured for them to step inside. “Hurry up, then. Let’s get this over and done with. I’ve an appointment in a few moments.” He turned on his heel and stalked toward a set of open double doors off the foyer.

“I do beg your pardon, sir. But we’ll need a complete statement,” Witherspoon said as he and the constable followed Tavistock. They came into a large drawing room. The decor was nicely done, but hardly opulent or unusual. The walls were painted a dark green and the windows covered with heavy gold damask curtains. A huge fireplace, over which hung the requisite portrait of an ancestor, dominated the far end of the room. Fringe-covered tables, bookcases and overstuffed furniture completed the picture.

'We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...