- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

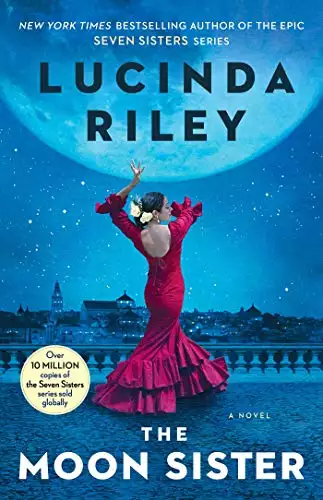

Synopsis

After the death of her father – Pa Salt, an elusive billionaire who adopted his six daughters from around the globe – Tiggy D'Aplièse , trusting her instincts, moves to the remote wilds of Scotland. There she takes a job doing what she loves; caring for animals on the vast and isolated Kinnaird estate, employed by the enigmatic and troubled Laird, Charlie Kinnaird. Her decision alters her future irrevocably when Chilly, an ancient gipsy who has lived for years on the estate, tells her that not only does she possess a sixth sense, passed down from her ancestors, but it was foretold long ago that he would be the one to send her back home to Granada in Spain. In the shadow of the magnificent Alhambra, Tiggy discovers her connection to the fabled gypsy community of Sacromonte, who were forced to flee their homes during the civil war, and to ‘La Candela' the greatest flamenco dancer of her generation. From the Scottish Highlands and Spain, to South America and New York, Tiggy follows the trail back to her own exotic but complex past. And under the watchful eye of a gifted gypsy bruja she begins to embrace her own talent for healing. But when fate takes a hand, Tiggy must decide whether to stay with her new-found family or return to Kinnaird, and Charlie…

Release date: February 19, 2019

Publisher: Atria Books

Print pages: 544

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Moon Sister

Lucinda Riley

1

I remember exactly where I was and what I was doing when I heard my father had died.”

“I remember where I was too, when it happened to me.”

Charlie Kinnaird’s penetrating blue gaze fell upon me.

“So, where were you?”

“At Margaret’s wildlife sanctuary, shoveling up deer poo. I really wish it had been a better setting, but it wasn’t. It’s okay, really. Although . . .” I swallowed hard, wondering how on earth this conversation—or, more accurately, interview—had veered onto Pa Salt’s death. I was currently sitting in a stuffy hospital canteen opposite Dr. Charlie Kinnaird. Even as he’d entered, I’d noticed how his presence commanded attention. It wasn’t just that he was strikingly handsome, with his slim, elegant physique clad in a well-tailored gray suit, and a head of wavy dark-auburn hair; he was simply someone who possessed a natural air of authority. Several of the hospital staff seated nearby had paused over their coffees to glance up and nod respectfully at him as he’d passed. When he’d reached me and held out his hand in greeting, a tiny electric shock had shot through my body. Now, as he sat opposite me, I watched those long fingers playing incessantly with the pager that lay between them, revealing an underlying level of nervous energy.

“?‘Although’ what, Miss D’Aplièse?” Charlie prompted, his voice exhibiting a soft Scottish burr. I realized he was obviously not prepared to let me off the hook I was currently hanging myself on.

“Umm . . . I’m just not sure Pa’s dead. I mean, of course he is, because he’s gone and he’d never fake his death or anything—he’d know how much pain it would cause all his girls—but I just feel him around me all the time.”

“If it’s any comfort, I think that reaction is perfectly normal,” Charlie responded. “A lot of the bereaved relatives I speak to say they feel the presence of their loved ones around them after they’ve died.”

“Of course,” I said, feeling slightly patronized, although I had to remember it was a doctor I was talking to—someone who dealt with death and the loved ones it left behind every day.

“Funny, really,” he sighed as he picked up the pager from the melamine tabletop and began to turn it over and over in his hands. “As I just mentioned, my own father died recently, and I’m plagued by what I can only describe as nightmare visions of him actually rising from the grave!”

“You weren’t close then?”

“No. He may have been my biological father, but that’s where our relationship began and ended. We had nothing else in common. You obviously did with yours.”

“Yes, although ironically my sisters and I were all adopted by him as babies, so there’s no biological connection at all. But I couldn’t have loved him more. Really, he was amazing.”

Charlie smiled at this. “Well then, surely that just goes to prove that biology doesn’t play a major part in whether we get on with our parents. It’s a lottery, isn’t it?”

“I don’t think it is actually,” I said, deciding there was only one “me” I could ever be, even in a job interview. “I think we’re given to each other for a reason, whether we’re blood relatives or not.”

“You mean it’s all predestined?” He raised a cynical eyebrow.

“Yes, but I know most people wouldn’t agree.”

“Me included, I’m afraid. In my role as a cardiac surgeon, I have to deal on a daily basis with the heart, which we all equate with emotions and the soul. Sadly, I’ve been forced to view it as a lump of muscle—and an often malfunctioning one at that. I’ve been trained to see the world in a purely scientific way.”

“I think there’s room for spirituality in science,” I countered. “I had a rigorous scientific training too, but there are so many things that science hasn’t yet explained.”

“You’re right, but . . .” Charlie checked his watch. “We seem to have wandered completely off track and I’m due in clinic in fifteen minutes. So, excuse me for getting back to business, but how much has Margaret told you about the Kinnaird estate?”

“That it’s over forty thousand acres of wilderness, and you’re looking for someone who knows about the indigenous animals who could inhabit it, wildcats in particular.”

“Yes. Due to my father’s death, the Kinnaird estate will pass to me. Dad used it as his personal playground for years, hunting, shooting, fishing, and drinking the local distilleries dry with not a thought for the estate’s ecology. To be fair, it’s not entirely his fault—his father and numerous male relatives before him were happy to take money from the loggers for shipbuilding in the last century. They stood back and watched as vast tracts of Caledonian pine forests were stripped bare. They didn’t know any better in those days, but in these enlightened times, we do. I’m aware that it will be impossible to turn back the clock completely, certainly in my lifetime, but I’m keen to make a start. I’ve got the best estate manager in the Highlands to lead the way with the reforestation project. We’ve also spruced up the hunting lodge where Dad lived, so we can let it to paying guests who want a breath of fresh Highland air and some organized shoots.”

“Right,” I said, trying to suppress a shudder.

“You obviously don’t approve of culling?”

“I can’t approve of any innocent animal being killed, no. But I do understand why it has to happen,” I added hurriedly. After all, I told myself, I was applying for a job on a Highland estate, where the culling of deer was not only standard practice but the law.

“With your background, I’m sure you know how the whole balance of nature in Scotland has been destroyed by mankind. There are no natural predators, such as wolves and bears, left to keep the deer population under control. Nowadays, that task is down to us. At least we can perform it as humanely as possible.”

“I know, although I have to be totally honest and tell you that I’d never be able to help out at a shoot. I’m used to protecting animals, not murdering them.”

“I understand your sentiments. I’ve had a look at your CV and it’s very impressive. As well as gaining a first-class degree in zoology, you specialized in conservation?”

“Yes, the technical side of my degree—anatomy, biology, genetics, indigenous animals’ behavioral patterns, and so on—was invaluable. I worked in the research department at Servion Zoo for a while, but I soon realized I was more interested in doing something hands-on to help animals, rather than just studying them from a distance and analyzing their DNA in a petri dish. I . . . just have a natural empathy with them in the flesh, and although I have no veterinary training, I seem to have a knack for healing them when they’re sick.” I shrugged lamely, embarrassed to be blowing my own trumpet.

“Margaret was certainly very complimentary about your skills. She told me you’ve been caring for the wildcats at her sanctuary.”

“I’ve done the day-to-day stuff, yes, but it’s Margaret who’s the real expert. We were hoping the cats would mate this season as part of the re-wilding program, but now that the sanctuary is closing and the animals are being re-homed, it probably won’t happen. Wildcats are incredibly temperamental.”

“So Cal, my estate manager, tells me. He’s not at all happy about adopting the cats, but they’re indigenous to Scotland and so rare, I feel it’s our duty to do what we can to save the breed. And Margaret thinks that if anyone can help the cats adjust to their change of habitat, it’s you. So, are you interested in coming up with them for a few weeks and settling them in?”

“I am, although the wildcats alone wouldn’t really be a full-time job once they’re in situ. Is there anything else I could do?”

“To be honest, Tiggy, so far I haven’t had much chance to think through future plans for the estate in detail. What with my job here and trying to sort out probate since my father passed away, I’ve been up to my eyes. But while you’re with us, I’d love it if you could study the terrain and assess its suitability for other indigenous breeds. I’ve been thinking about introducing red squirrels and native mountain hares. I’m also investigating the suitability of wild boar and elk, plus restocking the wild salmon in the streams and lochs, building salmon leaps and so forth to encourage spawning. There’s a lot of potential, given the right resources.”

“Okay, that all sounds interesting,” I agreed. “Although I should warn you, fish aren’t a speciality of mine.”

“Of course. And I should warn you that financial realities mean I can only offer a basic wage, plus board, but I’d be very grateful for any help you can give me. As much as I love the place, Kinnaird is proving a time-consuming and difficult proposition.”

“You must have known the estate would come to you one day?” I ventured.

“I did, but I also thought Dad was one of those characters who would creak on forever. So much so that he didn’t even bother to make a will, so he died intestate. Even though I’m his only heir and it’s a formality, it means another pile of paperwork I didn’t need. Anyway, it’ll all be sorted by January, so my solicitor tells me.”

“How did he die?” I asked.

“Ironically, he had a massive heart attack and was helicoptered in to me here,” Charlie sighed. “He’d already left us by then, borne upward on a cloud of whiskey fumes, so the postmortem indicated later.”

“That must have been tough for you,” I said, wincing at the thought.

“It was a shock, yes.”

I watched his fingers grab the pager once more, betraying his inner angst.

“Can’t you sell the estate if you don’t want it?”

“Sell up after three hundred years of Kinnaird ownership?” He rolled his eyes and gave a chuckle. “I’d have every ghost in the family haunting me for life! And if for no other reason, I have to try and at least caretake it for Zara, my daughter. She’s absolutely passionate about the place. She’s sixteen and if she could, she’d leave school tomorrow and come up and work at Kinnaird full-time. I’ve told her she has to finish her education first.”

“Right.” I looked at Charlie in surprise and immediately adjusted my view of him. This man seriously didn’t look old enough to have kids, let alone one who was sixteen.

“She’ll make a great laird when she’s older,” Charlie continued, “but I want her to live a little first—go to university, travel the world, and make sure committing herself to the family estate is really what she wants.”

“I knew what I wanted to do from the age of four, when I saw a documentary on how elephants were being killed for ivory. I didn’t take a gap year—just went straight to university. I’ve hardly traveled at all,” I said with a shrug, “but there’s nothing like learning on the job.”

“That’s what Zara keeps telling me.” Charlie gave me a faint smile. “I have a feeling the two of you will get on very well. Of course what I should do is give this up”—he indicated our surroundings—“and devote my life to the estate until Zara can take over. The problem is that until the estate’s in better shape, it doesn’t make financial sense to pack in my day job. And between you and me, I’m not even sure yet if I’m cut out for life as a country laird.” He checked his watch again. “Right, I must go, but if you are interested, it’s best you visit Kinnaird and see it for yourself. It hasn’t snowed up there yet, but it’s expected soon. You need to be aware that it’s as remote as it gets.”

“I live with Margaret in her cottage in the middle of nowhere,” I pointed out.

“Margaret’s cottage is Times Square compared to Kinnaird,” Charlie replied. “I’ll text you the mobile number for Cal MacKenzie—my estate manager—and also the landline at the lodge. If you leave messages on both, he’ll get one or the other eventually and call you back.”

“Okay. I—”

The beeping of Charlie’s pager interrupted my train of thought.

“Right, I really must go.” He stood up. “E-mail me with any more questions you have and if you let me know when you’re going up to Kinnaird, I’ll try to join you there. And please, think about it seriously. I really need you. Thanks for coming, Tiggy. Bye now.”

“Bye,” I said, then watched as he turned away and weaved through the tables toward the exit. I felt weirdly elated, because I’d experienced a real connection with him. Charlie seemed familiar, as though I’d known him forever. And since I believed in reincarnation, I probably had. I closed my eyes for a second and cleared my mind to try to focus on which emotion stirred first in me when I thought of him, and was shocked at the result. Rather than being filled with a warm glow about someone who might represent a paternal employer-like figure, another part of me altogether reacted.

No! I opened my eyes and stood up to leave. He’s got a teenage daughter, which means he’s far older than he looks and probably married, I chided myself as I walked through the brightly lit hospital corridors and out of the entrance into the foggy November afternoon. Dusk had already begun to fall over Inverness, even though it was only just past three o’clock.

Standing in the queue for the bus that would take me to the train station, I shivered—from cold or the tingle of excitement, I didn’t know. All I did know was that I was instinctively interested in the job, however temporary. So I found the number Charlie had given me for Cal MacKenzie, pulled out my mobile, and dialed it.

“So,” Margaret asked me that evening as we settled down for our customary cup of cocoa in front of the fire. “How did it go?”

“I’m going up to see the Kinnaird estate on Thursday.”

“Good.” Margaret’s bright blue eyes shone like laser beams in her wrinkled face. “What did you think of the laird?”

“He was very . . . nice. Yes, he was,” I managed. “Not at all what I was expecting,” I added, hoping I wasn’t blushing. “I thought he’d be a much older man. Possibly with no hair and a huge belly from too much whiskey.”

“Aye,” she cackled, reading my mind. “He’s easy on the eye and that’s for sure. I’ve known Charlie since he was a bairn; my father worked for his grandfather at Kinnaird. A lovely young man he was, though we all knew he was making a mistake when he married that wife of his. So young he was too.” Margaret rolled her eyes. “Their girl Zara’s sweet enough, mind you, if a little wild, but her childhood’s nae bin an easy one. So, tell me more about what Charlie said.”

“Apart from looking after the cats, he wants me to research indigenous breeds to introduce to the estate. To be honest, he didn’t seem very . . . organized. I think it would only be a temporary job while the cats settle in.”

“Well, even if it’s only a short wee while, living and working up on an estate like Kinnaird’ll teach you a lot. Mebbe there you’ll start to learn that you cannae save every creature that comes into your care. And that goes for lame ducks of the human variety too,” she added with a wry smile. “You have tae learn tae accept that animals and humans have their own destiny to follow. You can only do your best, an’ no more.”

“I’ll never toughen up to the plight of a suffering animal, Margaret. You know I won’t.”

“I do know, dear, and that’s what makes you special. You’re a wee slip o’ a thing, with a great big heart, but watch you don’t wear it out wi’ all that emotion.”

“So, what’s this Cal MacKenzie like?”

“Och, he comes across a bit gruff, but he’s a poppet underneath, is Cal. The place is in his blood an’ you’d learn a lot from him. Besides, if you don’t take this, where else will you go? You know me and the animals are gone from here by Christmas.”

Due to her crippling arthritis, Margaret was finally moving into the town of Tain, forty-five minutes’ drive from the damp, crumbling cottage we were currently sitting in. On the shores of Dornoch Firth, its twenty acres of hillside land had housed Margaret and her motley crew of assorted animals for the past forty years.

“Aren’t you sad about leaving?” I asked her yet again. “If it was me, I’d be crying my eyes out day and night.”

“Course I am, Tiggy, but as I’ve tried to teach yae, all good things must come tae an end. And with the will o’ God, new and better things will begin. No point in regretting what was, you just have tae embrace what will be. I’ve known this was coming for a long time now, and thanks tae you helping me I’ve managed an extra year here. And besides, my new bungalow has radiators yae can turn up when they’re wanted, and a television signal that works all o’ the time!”

She gave me a chuckle and a big smile, although I—who prided myself on being naturally intuitive—didn’t know if she really was happy about the future, or just being brave. Whichever it was, I stood up and went to hug her.

“I think you’re amazing, Margaret. You and the animals have taught me so much. I’m going to miss you all terribly.”

“Aye, well you won’t be missing me if yae take the job at Kinnaird. I’m a blow o’ wind down the valley and on hand to give you advice about the cats if you need it. And you’ll have tae visit Dennis, Guinness, and Button, or they’ll be missing you too.”

I looked down at the three scrawny creatures lying in front of the fire: an ancient three-legged ginger cat and two old dogs. All of them had been nursed back to health as youngsters by Margaret.

“I’ll go up and see Kinnaird and then make a decision. Otherwise, it’s home to Atlantis for Christmas and a rethink. Now, can I help you to bed before I go up?”

It was a question I asked Margaret every night and she responded with her usual proud reply.

“No, I’ll sit awhile here by the fire, Tiggy.”

“Sweet dreams, darling Margaret.”

I kissed her parchment-like cheek, then walked up the uneven narrow staircase to my bedroom. It had once been Margaret’s, until even she had realized that mounting the stairs every night was a number of steps too far. We had subsequently moved her bed downstairs into the dining room, and perhaps it was a blessing that there had never been funds to move the bathroom upstairs, because it still lay in the toe-bitingly cold outhouse only a few meters from the room she now used as her bedroom.

As I went through my usual routine of stripping off my day clothes, then putting on layers of night clothes before I climbed between the freezing-cold sheets, I was comforted that my decision to come here to the sanctuary had been the right one. As I’d told Charlie Kinnaird, after six months in the research department of Servion Zoo near Lausanne, I’d realized I wanted to take care of and protect the animals themselves. So I’d answered an ad I’d seen online and come to a crumbling cottage beside a loch to help an arthritic old lady in her wildlife sanctuary.

“Trust your instincts, Tiggy, they will never let you down.”

That’s what Pa Salt had said to me many times. “Life is about intuition, with a splash of logic. If you learn to use the two in the right balance, any decision you make will normally be right,” he’d added, when we’d stood together in his private garden at Atlantis and watched the full moon rise above Lake Geneva.

I remembered I’d been telling him that my dream was to one day go to Africa, to work with the incredible creatures in their natural habitat, rather than behind bars.

Tonight, as I curled my toes into a patch of bed I’d warmed up with my knees, I realized how far I felt from achieving my dream. Looking after four Scottish wildcats was not really in the big-game league.

I switched off the light, and lay there thinking how all my sisters teased me about being the spiritual snowflake of the family. I couldn’t really blame them, because when I was young I didn’t understand that I was “different,” so I’d just speak about the things that I saw or felt. Once, when I was very small, I’d told my sister CeCe that she shouldn’t climb her favorite tree because I’d seen her fall out of it. She’d laughed at me, not unkindly, and told me she’d climbed it hundreds of times and I was being silly. Then, when she had fallen out half an hour later, she had glanced away from me, embarrassed by the fact that my prophecy had come true. I’d since learned it was best to keep my mouth shut when I “knew” things. Just like I knew that Pa Salt wasn’t dead . . .

If he was, I would have known when his soul had left the earth. Yet I’d felt nothing, only the utter shock of the news when I’d received the call from my sister Maia. I’d been totally unprepared; no “warning” of the fact that something bad was coming. So, either my spiritual wiring was faulty, or I was in denial because I couldn’t bear to accept the truth.

My thoughts spun back to Charlie Kinnaird and the bizarre job interview I’d had earlier today. My stomach resumed its inappropriate lurches as my imagination conjured up those startling blue eyes and the slim hands with the long, sensitive fingers that had saved so many lives . . .

“God, Tiggy! Get a grip,” I muttered to myself. Maybe it was simply that—living such an isolated life—attractive, intelligent men were not exactly streaming through the door. Besides, Charlie Kinnaird had to be ten years my senior at least . . .

Still, I thought, as I closed my eyes, I was really looking forward to visiting the Kinnaird estate.

Three days later, I stepped off the little two-carriage train at Tain and walked toward a battered Land Rover—the only vehicle I could see outside the front entrance to the tiny station. A man in the driver’s seat rolled down the window.

“You Tiggy?” he asked me in a broad Scottish accent.

“Yes. Are you Cal MacKenzie?”

“I am that. Climb aboard.”

I did so, but struggled to close the heavy passenger door behind me.

“Lift it up, then slam it,” Cal advised me. “This tin can has seen better days, like most things at Kinnaird.”

There was a sudden bark from behind me, and I twisted round to see a gigantic Scottish deerhound sitting in the backseat. The dog edged forward to sniff my hair before giving my face a rough-tongued lick.

“Och, Thistle, down with you, boy!” Cal ordered.

“I don’t mind,” I said, reaching back to scratch Thistle behind the ears, “I love dogs.”

“Aye, but don’t start pampering him, he’s a workin’ dog. Right, we’re off.”

After a few false starts, Cal got the engine going and we drove through Tain—a small town fashioned out of dour gray slate—which served a large rural community and housed the only decent supermarket in the area. The urban sprawl soon disappeared and we drove along a winding road with gentle, sloping hills covered in clumps of heather and dotted with Caledonian pines. The tops of the hills were shrouded in thick gray mist, and on turning a corner, a loch appeared to our right. In the drizzle, it reminded me of a vast gray puddle.

I shivered, despite Thistle—who had decided to rest his shaggy gray head on my shoulder—warming my cheek with his hot breath, and remembered the first day I’d arrived at Inverness Airport almost a year ago. I’d left a clear blue Swiss sky and a light dusting of the first snow of the season on top of the mountains opposite Atlantis, only to find myself in a dreary facsimile of it. As the taxi had driven me to Margaret’s cottage, I’d truly wondered what on earth I had done. A year on, having lived in the Highlands throughout all four seasons, I knew that when the spring came, the heather would bring the hillsides alive with the softest purple, and the loch would shine a tranquil blue under a benevolent Scottish sun.

I glanced surreptitiously at my driver: a stocky, well-built man with ruddy cheeks and a head of thinning red hair. The large hands that clutched the wheel were those of a man who used them as his tools: fingernails ingrained with dirt, covered in scratches, and the knuckles red from exposure. Given the physically punishing job that Cal did, I decided he must be younger than he looked and put him somewhere between thirty and thirty-five.

Like most people I’d met around here, who were used to living and working on the land and isolated from the rest of the world, Cal didn’t speak much.

But he is a kind man . . ., my inner voice told me.

“How long have you worked at Kinnaird?” I broke the silence.

“Since I was a wee one. My father, grandfather, great-grandfather, and great-great-grandfather afore me did the same. I was out with my pa as soon as I could walk. Times have changed since then and that’s for sure. Changes bring their own set o’ problems, mind. Beryl isnae pleased tae have her territory invaded by a bunch o’ Sassenachs.”

“Beryl?” I questioned.

“The housekeeper at Kinnaird Lodge. She’s been workin’ there o’er forty years.”

“And ‘Sassenachs’?”

“The English; we have a load of poncey rich folk from across the border arriving tae spend Hogmanay at the lodge. An’ Beryl’s nae happy. You’re the first guest since it’s been renovated. The laird’s wife was put in charge and she didnae skimp on anything. The curtain bill alone must ha’ run intae thousands.”

“Well, I hope she hasn’t gone to any trouble for me. I’m used to roughing it,” I said, not wanting Cal to think I was in any way a spoiled princess. “You should see Margaret’s cottage.”

“Aye, I have, many a time. She’s the cousin o’ my cousin, so we’re distantly related. Most folk are around these parts.”

We lapsed into silence again as Cal turned a sharp left by a tiny run-down chapel with a weathered For Sale sign nailed lopsidedly to one of its walls. The road had narrowed and we were now driving through open countryside, with drystone walls on either side keeping the sheep and cattle safely corralled behind them.

In the distance, I could see gray clouds hanging atop further mountainous terrain. The odd stone homestead appeared sporadically on either side of us, plumes of smoke belching from the chimneys. Dusk was fast descending as we drove on and the road became pitted with potholes. The old Land Rover’s suspension was seemingly nonexisten

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...