Pastor Thomas drones on about Clementine May, the third closed-casket funeral in Sanctum, Alabama since I came down six weeks ago.

“She was a good woman,” he says. Pastor Thomas is an old white man, with bulbous green eyes and a bad case of male-pattern baldness. His voice is cool and calm, and so quiet. He’s nothing like Pastor Pride at my old church, with his booming voice and permanent sheen of sweat on his brow. Not that I ever went that much. “Clementine will be missed. Her unshakable character and selflessness are an inspiration. Congregation, take note of what kind of woman she was.”

What the hell is he talking about? The little I know about Clementine is that she frequently fell asleep in front of the only grocery store in town and gave that old-lady candy to kids. Sweet, but I wouldn’t call that “unshakable character.” Everyone else must know what he means, though; they’re nodding slowly, some murmuring prayers. No one’s crying. They’re staring at Pastor Thomas with ashen faces and grim precision. I squirm in the uncomfortable pew, trying not to scratch at the lace at the end of my dress. Maybe something happened with Clementine before I arrived.

Jade nudges my arm. She points to a handwritten note on the obituary. Poor Clementine. She was so nice.

She offers me the pencil, and I write a note back. Yeah but it’s not exactly unusual for here.

A flash of something crosses Jade’s face—fear?—but it’s quickly replaced by innocent confusion. The corners of Jade’s mouth pinch downward as she scribbles on the paper.

What do you mean?

She can’t be serious. It’s the third funeral in six weeks! There’s a whopping four hundred people in Sanctum, so three people dying is a significant population loss. I start to write again, but Allison nudges me.

“Avie, Jade,” Allison whispers in my ear. “They’re watching y’all.”

Sure enough, I look up and straight into Auntie’s death glare from the choir stand. Jade immediately crumples up the obituary and stares straight ahead. I do too, but slower. I know I’m lucky to be here, but Auntie is way too strict. We weren’t even talking. But fine, while I’m here, I’ll be good. Only two more weeks, and then I’m free.

Pastor Thomas talks about Clementine’s life and the family in Chicago she left behind (strangely absent from the funeral). Finally, he motions for us to stand. I scramble to my feet, fighting the sleep tugging at my eyelids.

Pastor Thomas meets the eyes of everyone in the front row. “Remember, no one goes into Red Wood.”

“Yes, Pastor,” the people chant. Unease crawls up my arms like goose bumps. God, this place is so weird.

“It’s time for the final prayer,” Pastor Thomas says.

“May the Lord bless their sacrifice,” a few hundred people say in unison, “and may the Lord protect us from the Serpent’s fangs and lying tongue.”

Pastor Thomas eyes the congregation, his face pale and serious. “Amen.”

With that, it’s over. Everyone starts talking in hushed murmurs, gathering their things. I stand and stretch, ignoring the glances my way. The air is thick and heavy, so heavy I can’t stand it. I bump Jade’s arm playfully. “What’s next? I’m starving.”

“Have some respect,” Jade mumbles, her hands fiddling with her purse. “Can we at least get out of the church?”

I have to bite back an unkind reply. Jade’s my cousin, a little over two years younger than me, but she definitely didn’t inherit my sense of humor. I can’t really blame her, though. Growing up in this weird-ass town’ll suck the fun out of anyone.

“I’m gonna talk to Pastor Thomas,” Allison says, flicking her blond hair out of her eyes. Her bangs are a little too long, so she’s always moving them out of her face. “You don’t have to wait for me.”

“We will,” I say quickly. Too quickly? No, Allison’s smiling, the warm one that reaches her soft blue eyes.

“Thanks!” she says. “Won’t take long, promise.”

Jade and I wave, and she heads toward the pastor’s office on the second floor. On the way, an older woman approaches her and gives her a yellow plastic bag I recognize from John’s grocery store. Allison nods graciously and tries to move away, but she’s stopped by a middle-aged guy with a beer gut. He drops something into her palm, which Allison promptly stores in her pocket while she talks to him.

“She’s popular,” I say, almost to myself. This happened the last few times I came to church too. She’s like a church celebrity.

“Jealous?” Jade says, smirking at me. I shoot her a poisonous look, but she just laughs and heads to the door.

We wander outside and sit on the porch steps. No one is milling around; the parking lot is half-empty already. It’s like everyone is in a rush to get home. Even on non-funeral days, I hardly ever see anyone out shopping or hanging out in restaurants. I know it’s a small town, but this can’t be normal. I know it’s not normal.

“I want to go for a run after this,” I tell Jade, tapping my fingers on my knee.

Jade doesn’t look up from her phone. “Mom’ll kill you.”

Yeah, I know. Auntie is strict about her rules: don’t go into Red Wood, the thick miles-wide forest behind her house; no going outside after dark (that includes running); come straight home after funerals. Among a million other things. Before, when I’d visit Auntie and Jade on Thanksgiving and Christmas, I thought it was Auntie being a hard-ass. But now that I’ve been here for six weeks in a row, I’m starting to get nervous. I watch people pour out of the church, silent, grim. Population of four hundred, and at least three hundred packed into the single massive church in town. And not just for Clementine. The other two funerals were like this too. All three older people, not sick; here one day, dead the next. I tap my fingers on my thigh. I don’t think Auntie is just being strict. I think something is wrong with Sanctum and they all know it.

I’m mulling over what the hell is wrong with this place when a woman and her kid approach us. I recognize her—Mrs. Brim, Deacon Brim’s wife. She’s a white woman with red hair, tall and gaunt. Her clothes are always a little too big. She smiles when she sees us. “Hey, girls. Waiting on the doctor?”

“No,” I answer, because Jade hasn’t looked up from her phone, “we’re supposed to go straight home. Which sucks, but whatever.”

Mrs. Brim laughs. “Dr. Roberts is a strict lady. Runs the choir stand with an iron fist!”

Yeah, I bet. Mrs. Brim moves a strand of hair out of her face, and I notice a bandage wrapped around her wrist. She’s still wearing her sweater too, despite it being a hundred degrees out here. “What happened to your wrist?” I ask.

Mrs. Brim’s smile wavers, but it’s back in a second. “I had an accident at home. Delilah left her Legos in the kitchen, and bam! There I went.”

I glance at the kid behind her, Delilah. She’s crouched, hugging her knees. She draws a picture of two people in the dirt, one tall, one short. She draws Xs over their eyes.

“Ouch,” Jade says, oblivious to the weird-as-hell kid. “Did Mom look at it for you? It seems kinda swollen.”

Mrs. Brim starts to answer, but Deacon Brim appears on the front steps. He’s a muscular man, with short brown hair and small, mean eyes. He ignores Jade and me and nods to Mrs. Brim. “We’re leaving.”

“Okay…Bye, girls! See you both on Sunday.” She grins at me. “I’ll talk to Dr. Roberts about letting you both loose every once in a while.”

Jade and I wave to Mrs. Brim as she gathers Delilah, and they walk to a sleek black SUV. We don’t speak until they’ve driven away.

“Do you think she’s okay?” I say, watching the car disappear.

“I don’t know,” Jade says, frowning at the place where Mrs. Brim stood. “But I do know it’s none of our business.”

Her comment irritates me. It is our business. It’s everyone’s business if Mr. Brim is a wife beater. But I don’t have any proof, just a hunch, and Mrs. Brim probably wouldn’t tell me, an eighteen-year-old “outsider,” anything. It’s pointless; the church would probably protect him. Maybe she’d even protect him. I curl my fingers on my knee. Someone needs to hurt Mr. Brim’s wrist. See how he likes it.

Allison emerges from the church, rejoining us. Thoughts of Mrs. Brim all but disappear. “Sorry I made y’all wait!”

“That’s okay,” I say, standing. “I was thinking we should go for a walk.”

“You know Mom hates it when we’re not home after funerals,” Jade says, annoyance at the edge of her voice.

Jesus, someone tell this kid to lighten up. “It’s a walk. It won’t kill us, Goody Two-shoes.”

Jade’s brow furrows, and I know we’re about to fight.

“Wait, wait,” Allison says. She pushes in between me and Jade. “Let’s go to the park. It’s right by your house, so if you need to leave quick, it’ll be fine.” She smiles at me, and the bottom of my stomach does a tiny somersault. “Okay?”

As if I could say no. “Okay,” I tell her. “Lead the way.”

Allison leads me and Jade away from the church. She’s still holding the yellow plastic bag from the old woman. I sneak a peek—looks like vegetables. That’s nice; old ladies sharing their gardens with her. That’s also normal. But as we pass unsmiling adults in a hurry to get home and a few listless, quiet kids staring at the ground, I’m reminded that Sanctum is anything but normal.

The whole town is like this. When I came down from Atlanta a month and a half ago, I didn’t notice it right away. Too angry, I guess. But slowly, as we had funerals every two weeks, as the town glared at me, something felt wrong. I can’t explain it. It’s summer, but the whole town feels dreary, lifeless. Streets are empty, devoid of cars and people. Kids don’t run in their yards and play. Dogs don’t bark. It’s like the town is holding its breath in case someone is listening.

“So,” I say, loud to dispel the eerie quiet, “I was thinking about Sanctum.”

“Thinking? You? Dangerous.” Jade laughs, but also glances at Allison. Allison doesn’t say anything.

“I was thinking…” I walk backward, my hands behind me. “Something feels kinda weird about this place. I mean, it’s the third funeral in six weeks. Here one day, gone the next.”

“People die of old age all the time,” Jade says. She won’t look at me, her gaze stubbornly on something behind me.

“Three in a row, all two weeks apart? All of them closed caskets?”

Jade and Allison don’t say anything, looking everywhere but at me. The unease from before is back in full force. They know something, and they’re not telling me.

“Well, what about that noise?” I ask. The night before someone dies, there’s a rattling sound that’s loud enough to carry through the whole town. Three times it’s woken me up from a dead sleep. Three funerals.

“The wind gets up at night sometimes,” Allison says. “It tears down the tree branches, and since you live right by Red Wood, it’s probably loud.”

Is she serious? She can’t think I’d actually believe that excuse. But it looks like she does; her blue eyes finally meet mine, and there’s an undercurrent of desperation in them. She wants me to believe her.

“There, see?” Jade says, kicking a rock at her feet. “Nothing to worry about. You’re being paranoid, Avie.”

I’m so frustrated, I could scream. “We’re really ignoring this? Seriously?”

Allison looks at me, her eyebrows scrunched together. “Everything’s fine, Avie. I promise.”

I sigh, defeated. If they won’t talk, no one will. If I want to know something, I’ll have to figure it out myself.

“Okay, fine.” I wipe my hands on the front of my itchy dress. “Don’t tell me about the serial killer or whatever. At least he only takes old people.”

Allison and Jade laugh nervously, but they don’t deny what I said. Fucking yikes.

We walk in heavy silence until we reach the park. It’s a pathetic collection of ancient swings, rusted metal slides, and rotten-wood playhouses. The only reason I come here at all is the gravel track looping the length of the park. Auntie won’t let me run in town, so this is the only place to practice.

I start to wander to a swing and sit down, but I stop. Near the entrance is a massive stone slab with a ton of names on it. There’s no marker or anything, so I thought it was a Civil War memorial and firmly ignored it. But today, I slow down and really look at it. It has names, like I thought, but the last few entries are newer. The last one is Clementine May.

“If the funerals are from old people dying of old age,” I say, running my fingertips over Clementine’s newly etched name, “then why is there a memorial for them?”

There’s a thick, unbearable silence. I don’t turn around to face Jade and Allison, a sick feeling in my gut. Something big is happening in this town. Something bad. I don’t have any proof, but I don’t need it; the silence of Jade and Allison tells me all I need to know.

“Avie, let’s go home.”

I turn around, and Jade has her thin arms crossed over her chest. Her expression is hard to read—anxious, confused, pleading.

“Mom’ll kill us if we’re not back by the time she gets home from the cemetery. Please.”

I turn back to the memorial, struggling to sort out my thoughts. I’m unnerved because they’re hiding something from me, clearly, but I’m not stupid. Maybe there’s a reason why I’m not supposed to know what’s going on in Sanctum. And so far, the victims have been sweet old ladies, so I guess I shouldn’t be too worried about myself. I take a breath, in through the nose, out through the mouth. I’ll play along for now. I just need to survive two more weeks, and then whoever’s making old people disappear won’t be my problem anymore. Though I’m a little worried about leaving Jade behind when I go to school….

“Okay, we—”

“What’re you kids doing?”

I know that voice. I turn around, my stomach sinking. Sheriff Kines strides toward us, hands on his belt. Dangerously close to his gun. He looks at me, his gray eyes like steel. “You know you’re supposed to go straight home after the service.”

I back up so I’m standing with Allison and Jade. Jade’s practically trembling, and for good reason. Sheriff Kines is a huge man, not only wide, but tall too. He towers over us, looking down his long nose at us like we’re bugs. He’s got his police dog with him today, an unpleasant German shepherd that has bitten at least three people. The black-and-tan dog looks at me, nose twitching, ears pricked. I bet it’d bite me too if the sheriff ordered it to.

I give the sheriff my best smile. “We’re taking a walk. We all grieve in our own ways.”

“A smart mouth’ll get you in trouble in this town,” he says.

I keep smiling, but I can feel it turning into a grimace. No one can take a joke here.

“Sorry, Sheriff,” Allison says, coming to rescue me. “We were just headed home. We’ll definitely be in by dark.”

Sheriff Kines nods stiffly. He looks at me one more time, his eyes narrowed. “Don’t let newcomers get y’all in trouble.”

“Oh, come on—”

“Yes, sir.” Jade interrupts me, grabbing my arm and dragging me back toward Auntie’s house. “Sorry again.”

The sheriff stares as we leave the park. Then he leans down and says something into the radio on his uniform. My stomach fills with dread every step of the way home.

—

After a wordless journey home and a quick goodbye to Allison, I climb the steps to Auntie’s guest room. It’s a stale, tired beige, with that old-people flowered print lining the walls and a white comforter draping the bed. This was my grandmother’s room before she passed away five years ago. We weren’t close, but it’s still a little weird to stay in a dead woman’s bedroom. Jade won’t come in here if she’s alone.

I pace the room for a bit, my fingers tapping on my thigh. I want to go for a run, but Auntie would have an aneurysm. If I don’t practice, though, my times will be terrible when I get to school. Coach Anders used to say I’m too easygoing and don’t take track seriously. And I mean, he’s kinda right. I run because it’s fun and relaxing. The scholarship money to University of Georgia is just a bonus. A damn good bonus, but still.

I climb onto the bed and lie down, frowning at the popcorn ceiling. I put my feet to the sky, then roll to my side, then to my back. I’m bored. Maybe I can sneak out tonight after Auntie goes to bed. Then again, with all these dead people, should I risk it? My arms itch as I think about Clementine’s closed casket. They were all closed, all three of them. Why haven’t I ever seen a body?

I pull my phone from my pocket and scroll through the top few texts, hoping for distraction. Jade and Allison, of course, but I can talk to them anytime. Lindsay—no, she’s still in France for the summer. Wish I was that lucky. Kendra—definitely not. I wince when I think about how we left things. My thumb grazes over Mom’s name, and I get a pang so sharp, I have to sit up. Flutterings of panic touch my chest. I breathe in through the nose, out from the mouth to calm down, just like Coach taught me. I’m okay. I can survive a few more weeks, and then UGA athletes are scheduled to go to campus on August 2 for orientation. Auntie will drive me, Jade will complain the whole time because she gets carsick, and maybe Mom will meet us there and help me move in. Two more weeks, and everything will be fine.

I turn my phone over so I can’t see the screen and close my eyes.

The sound of footsteps on the stairs makes my eyes pop open. Dinnertime, probably. I swing my aching legs off the bed and sit up as Auntie appears in the doorway of the guest room.

I grin at her, but she doesn’t smile back. She’s still wearing her floral church dress but looks severe and intimidating. She’s so tall—at least a head taller than me, and I’m five foot eight—and her sharp brown eyes will cut anyone down if they’re not careful.

“What’s up, Auntie?”

“I heard you were in the park instead of at home.” Her voice is lifeless, but her eyes are like fire.

I grit my teeth against my smile. “Just took a walk.”

Auntie glares for a moment more, and then her expression softens. She comes to my side and sits on my bed. “What am I going to do with you, Latavia?”

I can feel my shoulders relaxing. Auntie is strict and disciplined (have to be to put yourself through medical school), but she’s not so bad. And I owe her a lot, so I could be a better house guest. “You don’t have to do anything. The sheriff chased us home, anyway.”

“I don’t have to tell you why that worries me.”

Yeah, she doesn’t. I sigh heavily. “Auntie, can’t we go somewhere, do something? Anything. I’m bored to tears.”

“You can have fun at UGA,” she says, shaking her head. The motion makes the soft ceiling-fan lights catch on the pendant she always wears. It’s like a locket, but the picture part is huge. I always wondered whose picture is in there. Maybe Jade’s dad, who I’ve never seen or heard of. “Latavia, listen to me. I know it’s tough, and you’re having a hard time right now, but these rules are to protect you.”

“From the serial killer?” I don’t expect a real answer, but the flash of fear on Auntie’s face surprises me.

“Don’t speak about things you don’t know.”

“I would know if someone would tell me! I’m not stupid. Something’s bad wrong with this town.”

Auntie closes her eyes. “You only have two weeks here. Do what I say until then, okay? Everything will be fine.”

Everything will be fine. That’s what Allison said too. My skin crawls with apprehension and with it, anger. Auntie is hiding something, just like Allison and Jade. Why won’t anyone tell me what the hell is happening here? But…Auntie also took me in when I had no place to go. She’s the reason I don’t have to be homeless for three months while I wait for school to start. I take a deep breath to calm myself. If she wants to keep some secrets, I’ll let her. Two more weeks, and I’ll be gone.

I open my mouth to tell her okay, I’ll stay home and die of boredom, but something cuts me off. A sound. I pause, listening—a soft chaka, chaka. All the color drains from my aunt’s face.

“No…,” she says. “No, it’s too soon. There aren’t any volunteers. It’s too soon!”

The sound gets louder, until it’s almost deafening. A rattling sound.

Something tells me we’re about to have another funeral.

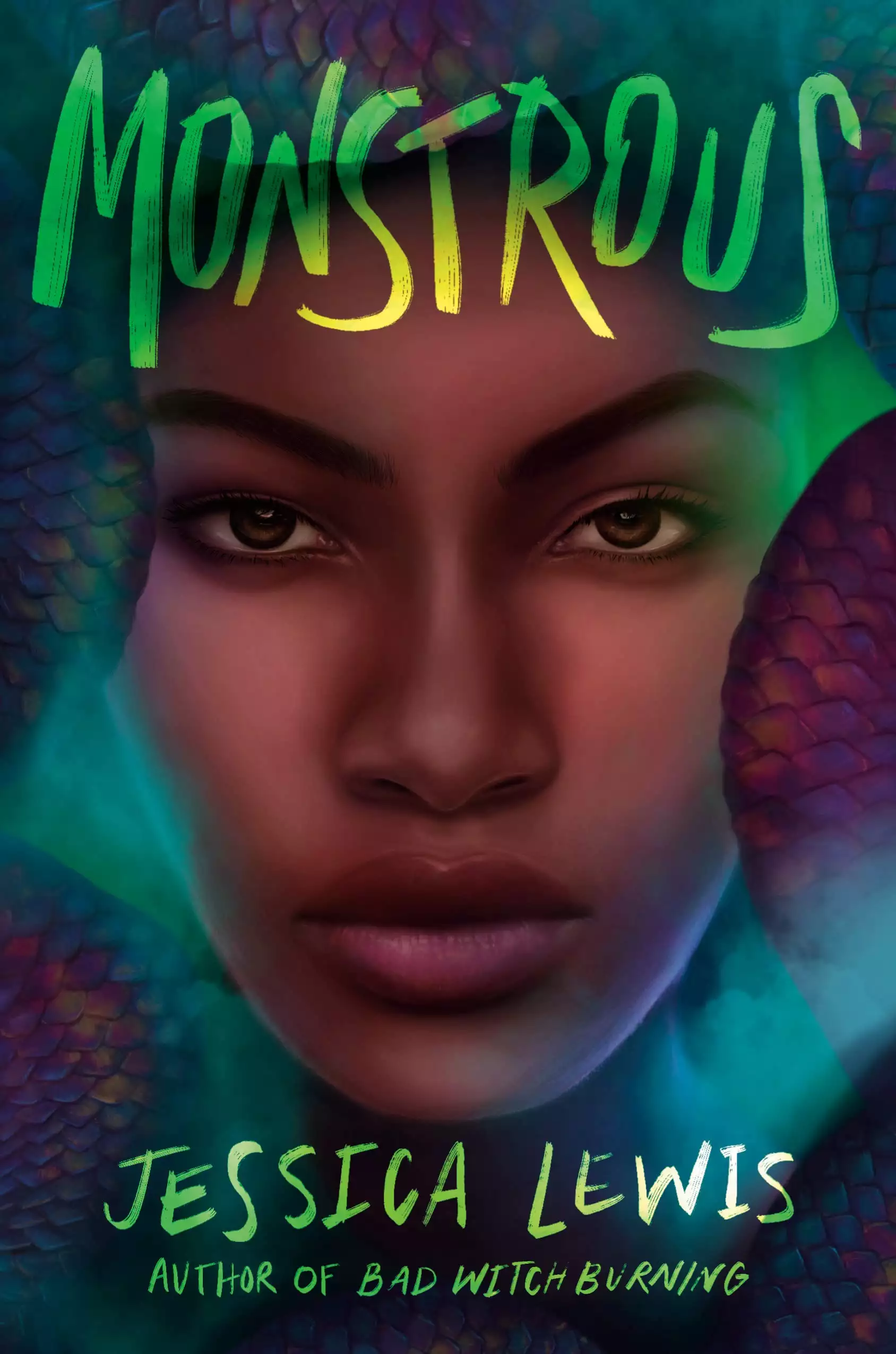

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved