- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

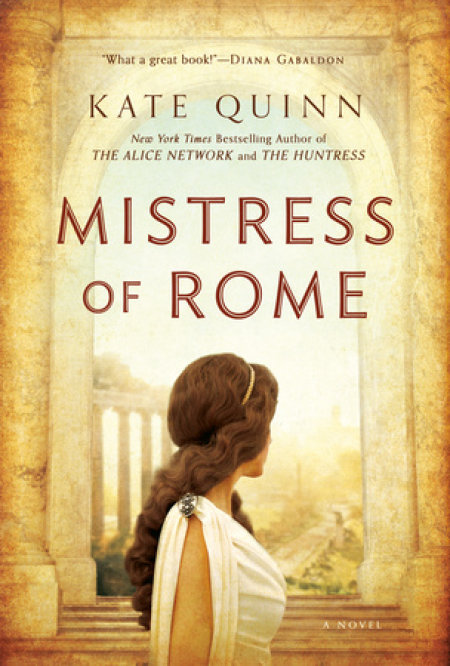

Synopsis

Thea is a slave girl from Judaea, passionate, musical, and guarded. Purchased as a toy for the spiteful heiress Lepida Pollia, Thea will become her mistress's rival for the love of Arius the Barbarian, Rome's newest and most savage gladiator. His love brings Thea the first happiness of her life, but that is quickly ended when a jealous Lepida tears them apart.

As Lepida goes on to wreak havoc in the life of a new husband and his family, Thea remakes herself as a polished singer for Rome's aristocrats. Unwittingly, she attracts another admirer in the charismatic Emperor of Rome. But Domitian's games have a darker side, and Thea finds herself fighting for both soul and sanity. Many have tried to destroy the Emperor: a vengeful gladiator, an upright senator, a tormented soldier, a Vestal Virgin. But in the end, the life of the brilliant and paranoid Domitian lies in the hands of one woman: the Emperor's mistress.

Release date: April 6, 2010

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Mistress of Rome

Kate Quinn

One

APRIL, A.D. 82

The atmosphere at the Mars Street gladiator school was contented,convivial, and masculine as the tired fighters troopedin through the gates. Twenty fighters had sallied out to join themain battle of the Cerealia games, and fourteen had come back alive.A good enough average to make the victors swagger as they filedthrough the narrow torch- lit hall, dumping their armor into thewaiting baskets.

“. . . hooked that Greek right through the stomach! Prettiestpiece of work I . . .”

“. . . see that bastard Lapicus get it in the back from that Gaul?Won’t be looking down his long nose at us anymore . . .”

“. . . hard luck on Theseus. Saw him trip in the sand . . .”

Arius tossed his plumed helmet into the waiting basket, ignoringthe slave who gave him cheery congratulations. The weapons hadalready been collected, of course— those got snatched the momentthe fighting was done.

“First fight?” A chatty Thracian tossed his own helmet into thebasket atop Arius’s. “Mine, too. Not bad, huh?”

Arius bent to unlace the greaves about his shins.

“Nice work you did on that African today. Had me one of thosescrawny Oriental Greeks; no trouble there. Hey, maybe next time I’llget Belleraphon and then I’ll really make my fortune.”

Arius unlaced the protective mail sleeve from his sword arm,shaking it off into the basket. The other fighters were already troopinginto the long hall where they were all fed, whooping as they filedalong the trestle tables and grabbed for the wine jugs.

“Quiet, aren’t you?” The Thracian jogged his elbow. “So whereyou from? I came over from Greece last year— ”

“Shut up,” said Arius in his flat grating Latin.

“What?”

Brushing past the Thracian into the hall, he ignored the trestletables and the platters of bread and meat. He leaned over and grabbedthe first wine jug he saw, then headed off down another small ill- lithallway. “Don’t mind him,” he heard another fighter growl to theThracian. “He’s a sour bastard.”

Arius’s room in the gladiator barracks was a tiny bare cell. Stonewalls, a chair, a straw pallet, a guttering tallow candle. He sank down onthe floor, setting his back against the wall and draining half the jug ina few methodical gulps. The cheap grapes left a sour taste in his mouth.No matter. Roman wine was quick, and all he wanted was quick.

“Knock knock!” a voice trilled at the door. “I hope you aren’tasleep yet, dear boy.”

“Piss off, Gallus.”

“Tut, tut. Is that any way to treat your lanista? Not to mentionyour friend?” Gallus swept in, vast and pink- fleshed in his immaculatetoga, gold gleaming on every finger, magnolia oil shining onevery curled hair, a little silk- decked slave boy at his side. Owner ofthe Mars Street gladiator school.

Arius spat out a toneless obscenity. Gallus laughed. “Now, now,none of that. I came to congratulate you. Such a splendid debut. Whenyou sent the head flying clean off that African . . . so dramatic! I wasa little surprised, of course. Such dedication, such savagery, from onewho swore not an hour before that he wouldn’t fight at all . . .”

Arius took another deep swallow of wine.

“Well, how nice it is to be right. The first time I saw you, I knewyou had potential. A little old for the arena, of course— how old areyou, anyway? Twenty- five, thirty? No youngster, but you’ve certainlygot something.” Gallus waved his silver pomander languidly.Arius looked at him.

“You’ll get another fight in the next games, of course. Somethinga little bigger and grander, if I can persuade Quintus Pollio. A solobout, perhaps. And this time”— a glass- sharp glance— “I won’t haveto worry that you’ll deliver, will I.”

Arius aligned the wine jug against the wall. “What’s a rudius?”The words surprised him, and he kept his eyes on the jug.“A rudius?” Gallus blinked. “Dear boy, wherever did you hearabout that?”

Arius shrugged. They had all been waiting in the dark underthe Colosseum before their bout, nervous and excited, fingering theirweapons. Here’s to a rudius for all of us, one of the others had muttered.

A man who had died five minutes later under a trident beforeArius could ask him what it meant.

“A rudius is a myth,” Gallus said airily. “A wooden sword givenfrom the Emperor to a gladiator, signaling his freedom. I supposeit’s happened once or twice for the stars of the arena, but that hardlyincludes you, does it? One bout, and not even a solo bout— you’vegot a long way to go before you can call yourself a success, much lessa star.”

Arius shrugged.

“Such a dear boy.” Gallus reached out and stroked Arius’s arm.His plump fingers pinched hard, and his black peppercorn eyeslocked onto Arius’s with bright curiosity.

Arius reached out, picked up the tallow candle beside him, andcalmly poured a stream of hot wax onto the soft manicured hand.Gallus snatched his burned fingers away. “We really will have todo something about your manners,” he sighed. “Good night, then.Dear boy.”

As soon as the door thudded shut, Arius picked up the wine jugand drank off every drop. Letting the jug fall, he dropped his headback against the stones. The room wasn’t spinning anymore. Notenough wine. He closed his eyes.

He hadn’t meant to fight. He’d meant what he’d told Gallus,standing in the dim passage underneath the arena, hearing the roarsof the crowd and the screams of the wounded men and the whimpersof the dying animals. But the sword had been placed in his hand, andhe’d gone out with the others in the brisk group battle that served towhet the crowd’s appetite for the solo bouts, and he’d seen the Africanhe’d been paired to fight . . . and the black demon had uncoiledfrom its self- devouring circles in his brain and roared joyously downthe straight and simple path of murder.

Then suddenly he had been standing blinking in the sunlightwith another man’s blood on his face and cheers pouring down on hishead like a swarm of bees. Just thinking about those cheers broughtan icy sweat. The arena. That hellish arena. It spoiled his luck everytime. Even slaughtering its guards had failed to get him killed.After that savage beating seven months ago, he had awakened inbed. Not a soft bed; Gallus didn’t waste luxuries on half- dead slaves.Dragging himself painfully into the light, he heard for the first timeGallus’s voice: high, modulated, reeking of the slums.

“Can you hear me, boy? Nod if you understand. Good. What’syour name?”

Hoarsely he croaked it out.

Gallus tittered. “Oh, that’s absurd. A Briton, aren’t you? You barbariansalways have impossible names. Well, it won’t do. We’ll callyou Arius. A bit like Aries, the god of war. Quite catchy, yes, we cando something with that.

“Now. I’ve bought you, and paid a pretty price, too, for a half- deadtroublemaker. Yes, I know exactly why you were sentenced to thearena. You were part of a chain gang making repairs on the Colosseum,until you strangled a guard with his own whip. Very foolish,dear boy. Whatever were you thinking?” Gallus snapped for his littleslave boy with the tray of sweetmeats. “Well, then”— eating busily—“you can tell me for starts how you ended up working a chain gangin the Colosseum.”

“Salt mines,” Arius forced out through swollen lips. “In Trinovantia.Then Gaul.”

“Dear me. And how long have you been working in thosesinkholes?”

Arius shrugged. Twelve years? He wasn’t sure.

“A long time, clearly. That explains the strength of the arms andchest.” A plump finger traced over Arius’s shoulders. “Hauling rocksof salt up and down mountains for years; oh yes, it builds fine men.”A last lingering stroke. “One doesn’t learn to use a sword in themines, however. Where did you learn that, eh?”

Arius turned his face toward the wall.

“Well, no matter. Time to listen. You’ll do your fighting for mefrom now on, when and where I say. I am a lanista. Know what thatis? No? I thought your Latin was a little rough. Everything about youis a little rough, isn’t it? A lanista is a trainer, dear boy, of gladiators.You’re going to be a gladiator. It’s a good life as they go— women,riches, fame. You’ll take the oath now, and begin training as soon asthose bones patch up. Repeat after me: ‘I undertake to be burnt by fire,to be bound in chains, to be beaten by rods, and to die by the sword.’ That’sthe gladiator’s oath, dear boy.”

Arius told him hoarsely what he could do with his oath, and collapsedback into blackness.

It had been days before he could get out of bed, weeks before hisbones were whole, and nearly five months before his training in thegladiators’ courtyard was complete. His fellow fighters were pettycriminals and bewildered slaves scummed off the bottom of the market:a cheap cut- rate bunch. Arius slid indifferently into the school’sroutine: just one more thug with Gallus’s crude crossed- swords tattooon his arm. Better than the mines.

Rudius. The word came back to him. Sounded like a snake, not awooden sword. He didn’t see how getting a wooden sword from theEmperor made you free, but the mist- shrouded mountains of homerose up before his eyes, impossibly fresh and green and lovely.A wooden sword. He used wooden swords every day when hetrained. He always broke them, hitting too hard. An omen? Hethought back to the white- robed Druids of his childhood, dimlyremembered, smelling of mistletoe and old bones, reading the godsin every leaf’s fall. They’d call it a bad omen, breaking a woodensword. But he’d never had many good omens in his life.

He shook off the thought of home. The Mars Street school wasn’tbad. No women and riches as Gallus had promised, but at least nomerciless sun, no chains eating the flesh off his ankles, no uneasysleep on bare mountainsides. Here there were blankets and bread forthe days, wine to drown the nights, a quick death around the corner.Better than the mines. Nothing could be worse than the mines.The applause of the games fans flickered uneasily through hismind.

THEA

From the moment I saw Senator Marcus Vibius Augustus Norbanus,I longed to fix him up: give him a proper haircut, get theink stains off his fingers, take his slaves to task for pressing his toga sobadly. He had been divorced for more than ten years, and slaves takeadvantage when there’s no mistress of the house. I would have bet fivecoppers that Marcus Norbanus, who had been consul four times andwas the natural grandson of the God- Emperor Augustus, poured hisown wine and put away his own books just like any pleb widower.“Your name, girl?” he asked, as I offered a tray of little sweetmarchpane pastries.

“Thea, sir.”

“A Greek name.” He had deep- set eyes; friendly, penetrating,aloof. “But not, I think, a Greek. Something too long about the vowels,and the shape of the eyes is wrong. Antiochene, perhaps, but Iwould guess Hebrew.”

I smiled in assent, backing away and examining him covertly. Hehad a crooked shoulder that pulled him off- balance and made himlimp, but it was hardly visible unless he was standing. Seated he wasstill a fine figure of a man, with a noble patrician profile and thickgray hair.

Poor Marcus Norbanus. Your bride will eat you alive.“Senator!” Lepida danced in, fresh and lovely in carnelian silkwith strands of coral about her neck and wrists. Fifteen now, as I was;prettier and more poised than ever. “You’re here early. Eager to seethe games?”

“The spectacle always provides a certain interest.” He rose andkissed her hand. “Though I usually prefer my library.”

“Well, you must change your opinion. For I am quite mad for thegames.”

“Her father’s daughter, I see.” Marcus made a courtly nod toPollio.

Lepida’s father swept his eyes with just a hint of contempt overMarcus’s uncurled hair, the carelessly pressed toga, the mended sandalstrap. He himself was immaculate: snowy linen pleated razor- sharpand perfume heavy enough to tingle the nostrils. Still, no one wouldever mistake him for a patrician. Or Marcus Norbanus for anythingelse.

“So, you really know the Emperor’s niece?” Lepida asked herbetrothed as we left the Pollio house and sallied out into the Aprilsunshine. Her blue eyes were wide with admiration. “Lady Julia?”

“Yes, since she was small.” Marcus smiled. “She and her half- sisterwere playmates of my son’s when they were very young. They haven’tmet since they were children— Paulinus is with the Praetoriansnow— but I still visit Lady Julia now and then. She’s been very downcastsince her father died.”

The wedding morning of Lady Julia and her cousin Gaius TitusFlavius burst clear and blue as we went to watch them join hands atthe public shrine— on foot, since the litters would never get throughthe crowds. I was jostled from side to side by shoving apprentices,avid housewives, beggars trying to slip their hands into my purse.A baker in a flour- sprinkled apron trod heavily on my foot, and Itripped.

Marcus Norbanus caught my arm with surprising agility, settingme on my feet before I could fall. “Careful, girl.”

“Thank you, sir.” I fell behind, chagrined. He really was far tookind to be Lepida’s husband. I’d been praying devotedly for an ogre.

“Oh, look!” Abandoning Marcus’s arm, Lepida elbowed her wayto the front of the crowd. “Look, there they are!”

I peered over Pollio’s shoulder. The shrine of Juno, goddess ofmarriage— and the tall ruddy- cheeked young man beside the priestmust be the bridegroom. He was in high spirits, jostling and jokingwith his attendants. “He’s handsome,” Lepida announced. “Fat,though. Don’t you think?”

Marcus looked amused. “The Flavians tend toward heaviness,” hesaid mildly. “A family trait.”

“Oh. Well, he’s not really fat, is he? Just imposing.”

The blast of Imperial trumpets brazened in our ears. Servants inImperial livery began to wind past. The Praetorian Guard lined theroad in their ceremonial breastplates and red plumes, making way forthe bride. “Is that Lady Julia?” Lepida craned her neck.

I studied the Emperor’s niece curiously— the one who supposedlywanted to be a Vestal Virgin. She was very small, her hair straw- pale,her figure straight and childlike in the white robe. The flaming bridalveil drew all the color out of her face. Her pale lips were smiling, butshe didn’t really look— well, bridal.

“She doesn’t have the complexion for red,” my mistress said, toosoftly for her betrothed to hear. “Her skin’s like an unripe cheese. I’lllook much better at my wedding.”N

The bridal pair joined hands at the shrine, speaking the ritual words:Quando tu Gaius, ego Gaia. They exchanged the ritual cake, the rings.

The marriage contracts were signed. The priest intoned prayers, and abellowing white bull gave its blood in a gout over the marble steps asa sacrifice to Juno. Usually Imperial weddings were conducted moreprivately, but Emperor Domitian was a lover of public pomp. So wasthe public.

“She should smile,” Lepida criticized. “No one wants to see a bridelooking like a corpse on her own wedding day.”

Before the procession, the groom had to wrest his bride from hermother’s arms in symbolic theft. Lady Julia’s mother was dead; heruncle stood in for her. She folded the red veil back over her palehair and walked meekly into his arms. As the bridegroom used bothhands to jerk her away, my gaze shifted to the Emperor.

He was a tall man, vigorous and well made, a little more thantwice my age, reflecting back the sun in his gold- embroidered purplecloak and golden circlet. Thickset Flavian shoulders that would runto fat in his old age. Ruddy cheeks and broad, friendly features.

My eyes shifted back to his niece, huddled in the arm of her newhusband. I felt sorry for her. A slave feeling sorry for a princess— Idon’t know why. Then her eyes shifted, falling for a moment on mine,and in the instant before I dropped my gaze to the ground I saw thaton the day of her own wedding— a bright and beautiful spring daywhen the whole world stretched before her— Lady Julia Flavia feltlost and terrified and alone.

“Well, that’s that!” Pollio clapped his hands, and I jumped. “We’dbetter go on to the arena. The first show is very splendid, I assureyou. I found a dozen of the strangest striped horses from an Africantrader; he called them zebras— ”

On Senator Norbanus’s suggestion, we took a hired litter on ashortcut through Mars Street. I trotted behind on foot while Lepidasqueezed in beside her betrothed, hanging on his every word, lookingup at him through long black lashes. A spider reeling in the fly.

Pollio was still droning on about how clever he had been tobuy twenty tigers at a bargain price from India when the litter wasforced to pull up short. A huge cart blocked the road, ironbound andpadlocked, and a litter borne by six golden- haired Greeks. As wewatched, a gate barred like a prison swung open and a team of menmarched out. Armor gleamed beneath their purple cloaks as theyclimbed into the wagon, and their faces were somber under theirhelmets. Gladiators, on their way to the Colosseum.

“Gallus’s fighters.” Pollio twitched back the curtains for a betterlook, frowning. “ Third- raters, all of them. Still, they make good baitfor the lions. So would Gallus himself, if you ask me. That’s him inthe litter.”

A fat man with a fringe of oiled curls around his forehead leanedout through the orange silk curtains to shout through the gates.“You’re holding us up, dear boy.”

Out through the gates of Gallus’s school strode a big man,russet- haired, a Gaul or a Briton. He wore heavy iron plates overhis shins, a green kilt, an absurd helmet with green plumes. A mailsleeve protected his fighting arm, the leather straps passing over hisunprotected chest and scarred back. His face was granite- still— andI knew him.

The slave. The one who had fought back in the games of theEmperor’s accession months ago. I remembered weeping a littlefor him, the same way I wept when the lions fell in the arena withspears through their great chests. I’d thought he was dead. Even afterthe Emperor decreed mercy, they’d had to drag him out on a hooklike they did the dead lions. But he wasn’t dead. He was back: agladiator.

“Hurry up, Arius,” the lanista called impatiently from the litter.“We’re blocking the road.”

He caught the side of the wagon and vaulted up. Arius. So thatwas his name.

For once, I was longing to see the games.

The underground levels of the Colosseum hummed like the pipesof an aqueduct. Slaves rushed through the torch- lit passages,some with whetstones to sharpen the weapons, some with sharpsticks to prod the animals into a fury before they were released upinto the arena, some with great rakes to scrape up the dead. Somewherea lion screamed, or maybe a dying man.

“The main battle’s in two hours,” a steward barked at Gallus ingreeting, eyes raking over the gladiators. “Keep them out of the waytill then. Which one’s the Briton? He goes after the tigers finish offthose prisoners.”

A few hissed words from Gallus, and Arius found himself shunteddown a dark passage. Spring warmth never penetrated the bowels ofthe Colosseum; the passages were dank and cold. Fine clay dust filtereddown, shaken loose by the vibrations of the cheers.

A pulley carried Arius to the upper levels; a slave led him to agate and hastily shoved a sword and heavy shield at him. “Luck toyou, gladiator.” Arius waited, rasping a mailed finger up and downthe edge of the blade. Against the darkness he saw a wooden sword.The applause died down. Dimly he heard the voice of the gamesannouncer: “And now . . . wilds of Britannia . . . we bring you . . .Arius the Barbarian . . . playing the part of . . .”

With a clank of machinery the heavy gate cranked up. Blindingsunlight flooded the passage.

“ACHILLES, THE GREATEST WARRIOR IN THE WORLD!”

The cheering hit him like a wall as he strode out into the sunlight.Fifty thousand voices shouting his name. A blur of brightsilks and white togas, pale circles of faces and black circles of openmouths, backed by a roof of dazzling blue sky. He’d never seen somany people in his life.

He caught himself staring, and slammed down his visor. No needto know who Achilles was, or what kind of part he was playing. Killingwas killing.

The demon uncoiled joyfully in his gut.

The announcer’s voice again, hushing the cheers. “And now, fromthe wilds of Amazonia, we bring you fitting opponents to the mightyhero Achilles— ”

The gate at the other end of the arena rumbled. Arius shruggedhis cloak off and his sword up, shifting into a crouch.

“THE QUEEN OF THE AMAZONS AND HER CHAMPIONS!”Arius’s blade faltered.

Women. Five women. In plumed golden helmets and crescentmoonshields and gold anklets. Breasts bare for the audience to leerat. Slim bright swords raised high. Lips clamped into hard lines.The demon rage drained away. Left him cold and shaking. Hissword point dropped, brushed against the sand.

The red- plumed leader let out a kestrel shriek as she swoopeddown toward him.

“Oh, damn it,” he snarled, and brought up his sword.

He picked them off one at a time. The smallest first. No olderthan fourteen. She stabbed at him with more desperation than skill.He killed her quickly. Then the dark- haired one with the birthmarkon her shoulder. He clipped the sword out of her hand, turning hiseyes away as he hewed her down. Every stroke lasted a century.

In extreme slow motion he saw the leader cry out, trying to pullthem together. She knew what she was doing. Charging together,they might have brought him down. But they panicked and scattered.And, to the raucous enjoyment of the crowd, he chased themdown one at a time and slew them.

He just tried to do it fast.

The leader in her brave scarlet plumes, she was the last. She putup a good fight, catching his sword again and again on her slimshield. Her blade landed twig- light against his own. Her eyes showedhuge and wild through the visor.

He knocked her sword aside and drove his shield boss against herunprotected breast. Her neck arced in agony. She crumpled to thesand like a broken clay figurine.

Not dead. Not yet. Just strangling on her own blood, crushed ribstrying to expand. He took a tired step forward to cut her throat.

“Mitte! Mitte!”

The cry assailed his ears, and he looked up dumbly. All across the tiersof spectators, the thumbs called for mercy. The cheers were good- natured,the opinion unanimous: mercy for the last of the Amazons.

His eyes burned. Sweat. He flung the blade away and droppedto one knee to slide an arm under her shoulders. She was bleedingeverywhere—

Her eyes swept him feebly. A swaying hand reached up to tiltback his visor. And then he was jolted all the way down to his bonesas she spoke to him in a language he had not heard for more than adozen years. His own language.

“Please,” she rasped.

He stared at her.

She choked again on her own blood. “Please.”

He looked down into those great, desperate eyes.

“Please.”

He slid his hand up into her hair, turning her head back to exposethe long throat. She closed her eyes with a rattling sigh. He eased hisblade into the soft pulse behind her jaw.

When her crushed body was cold in his arms, he looked up. Hisaudience had gone silent. He rose, stained all over with her blood andweighed down by unbelieving eyes.

The demon’s fury roared up, and with all his strength he hewedhis sword sideways against the marble wall. He struck again andagain, feeling the muscles tear across his back, and at last the bladesnapped in two with a dissonant crack. He flung the pieces away, spaton them, then ripped the helmet from his head and flung that after.

Rage surged up in his throat and he shouted— no curses, just a longwordless roar.

They applauded him.

Applauded.

They cheered, they shouted, they screamed praise down on hishead like a stinging rain. They threw coins, they threw flowers, theysurged upright and shrieked his name. They stamped their feet androcked the marble tiers.

It was only then that he wept, standing alone in the greatarena surrounded by the bodies of five women and a thousanddownward- drifting rose petals.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...