- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

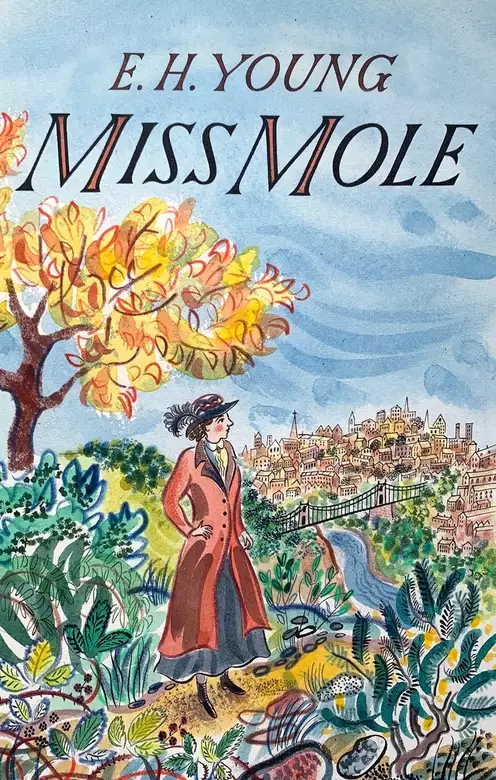

Synopsis

'Who would suspect her sense of fun and irony, of a passionate love for beauty and the power to drag it from its hidden places? Who would imagine that Miss Mole had pictured herself, at different times, as an explorer in strange lands, as a lady wrapped in luxury and delicate garments?' Miss Hannah Mole has for twenty years earned her living precariously as a governess or companion to a succession of difficult old women.Now, aged forty, a thin and shabby figure, she returns to Radstowe, the lovely city of her youth. Here she is, if not exactly welcomed, at least employed as housekeeper by the pompous Reverend Robert Corder, whose daughters are sorely in need of guidance. But even the dreariest situation can be transformed into an adventure by the indomitable Miss Mole. Blessed with imagination, wit and intelligence, she wins the affection of Ethel and her nervous sister Ruth. But her past holds a secret that, if brought to life, would jeopardise everything.

Release date: October 1, 2020

Publisher: Virago

Print pages: 250

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Miss Mole

E.H. Young

‘Yes, yes, I’ll come!’ Hannah called out hurriedly, and she glanced over her shoulder as the golden patch on the path disappeared. Mrs Gibson had shut the front door: she had returned to the problems which ought never to have arisen in her respectable house, and Hannah, freed from the necessity for action, for the expression of sympathy and the giving of advice, was able to admire the skill she had shown in these activities, but first, because she was grateful by nature as well as appreciative of herself, she offered up thanks for the timely justification of her faith in the interest of life. That faith had been persistent, though, latterly, it had demanded a dogged perseverance, and at the moment when she most needed encouragement it had been supplied. She would not ignore the creditable quickness with which she had grasped the opportunity offered; it was, indeed, only to those with seeing eyes and hearing ears that miracles were vouchsafed, and who but Hannah Mole, at her impact with Mrs Gibson’s broad bosom, would have had the prescience to linger after her apology and give Mrs Gibson time to recover her breath and explain why she stood outside her gate, bareheaded and in a flutter.

On the same spot Hannah now stood, a little breathless herself, through excitement and the effort to reconcile her good fortune with the small deception she had practised on her employer. The effort was not successful and she renewed her conviction that the power which controlled her life was not hampered by man’s conventional morality, otherwise, she would surely have been punished and not rewarded for the lie which had induced Mrs Widdows to send her companion shopping at the hour when she should have been mending Mrs Widdows’ second-best black dress. Yes, Hannah should have been knocked down by a motorcar or, worse still, have been robbed of her purse, for hiding the reel of silk and pretending she could not find it.

The crowded little sitting-room had been unbearably hot. A large fire blazed and crackled, the canary made sad, subdued movements in its cage, Mrs Widdows’ corsets creaked regularly, her large knees almost touched Hannah’s own, for the two women sat near each other to share the lamplight, and Hannah, luckier than the canary, had found a means of escape. Too wise to suggest that she should go out and buy the necessary silk, she had merely remarked with regret that it would be impossible for Mrs Widdows to wear the second-best dress on the morrow, and, at once, Mrs Widdows had indignantly driven her forth with orders to return quickly. And nearly two hours had passed and the silk was still in the shop. Hannah was indifferent about the silk, for the reel she had removed from the work-basket was in the pocket of her coat, and she was twopence halfpenny and an adventure to the good, but the passage of time was a serious matter, so serious that another hour or two would make no difference. She glanced up the street, and then down, and while she seemed to hesitate between duty and desire, she had already made her choice. She would go down, towards the traffic and the shops. By the light of the street lamp, she looked at the old-fashioned flat watch she carried in her handbag. It was six o’clock. Most of the shops would be shut, but there would be light and movement; tram-cars full of passengers would be leaping in their advance, like strange beasts rejoicing in their strength; people on foot would be streaming homewards from the city of Radstowe, and Miss Hannah Mole, who had no home of her own, would look at these people with envy but with the cynical reflection that some of those homes might be comparable to that of Mrs Widdows – stuffy and unkind, or to the one she had just left – holding tragedy maliciously streaked with humour. In nearly twenty years of earning her living, as companion, nursery governess or useful help, she had lost all illusions except those she created for herself, but these appeared at her command and, stirred by her late adventure, she was ready to find another in the approach of each person she met. In Prince’s Road, however, there were not many people and such as there were walked quietly, as though the influence of the old terraced houses on one side of the road were stronger than that of the later buildings on the other. It was the old houses that gave its character to the street and here, as elsewhere in Upper Radstowe, the gently persistent personality of the place remained, unmoved by any material or spiritual changes since the first red bricks were well and truly laid. It was like a masterpiece of portrait painting in which a person of another generation looks down on his descendants and dominates them through the union of the painter’s art and something permanent in himself. Even where the old houses had disappeared, their ghosts seemed to hover over the streets, and Hannah, too, walked quietly, careful not to disturb them. In no other place of her acquaintance did the trees cast such lovely shadows in the lamplight, and on this windless night the leaves were patterned with extraordinary, ethereal clearness on the pavement. Now and then she paused to look at them, puzzled that the reflected object should always seem more beautiful than the original, and eager to find some analogy to this experience in her mental processes.

‘Not the thing itself, but its shadow,’ she murmured, as she saw her own shadow going before her, and she nodded as though she had solved a problem. She judged herself by the shadow she chose to project for her own pleasure and it was her business in life – and one in which she usually failed – to make other people accept her creation. Yes, she failed, she failed! They would not look at the beautiful, the valuable Hannah Mole: they saw the substance and disapproved of it and she did not blame them: it was what she would have done herself and in the one case when she had concentrated on the fine shadow presented to her, she had been mistaken.

She pushed past that thought with an increase of her pace and reached the wide thoroughfare where the tram-cars clanged and swayed. Here she paused and looked about her. This part of Radstowe was a new growth, it was not the one of her affections, but on this autumn evening it had its beauty. The broad space made by the meeting of several roads was roughly framed in trees, for in Radstowe trees grew everywhere, as church spires seemed to spring up at every corner, and the electric light from tall standards cast a theatrical glare on the greens and browns and yellows of their leaves.

At Hannah’s left hand, in a shrubbery of its own, there stood a building, in a debased Greek style, whither the Muses occasionally drew the people of Radstowe to a half-hearted worship. The darkness in which it was retired, suddenly illuminated by the head-lights of a passing car, dealt kindly with its faults, and there was mystery in its pale, pillared façade, a suggestion of sensitive aloofness in its withdrawal from the road. When Hannah passed this temple in the daytime, her long nose would twitch in derision at its false severity and the rusty-looking shrubs dedicated to its importance in the aesthetic life of Radstowe – had the gardener, she wondered, chosen laurels with any thought beyond their sturdiness? – but now it had an artificial charm for her: she could ignore the placards on the enclosing railings and see it as another example of the city’s facility for happily mixing the incongruous.

She stood on the pavement, a thin, shabby figure, so insignificant in her old hat and coat, so forgetful of herself in her enjoyment of the scene, that she might have been wearing a cloak of invisibility, and while she watched the traffic and saw the moving tram-cars like magic-lantern slides, quick and coloured, no one who saw through that cloak would have suspected her power for transmuting what was common into what was rare and, in that occupation, keeping anxious thoughts at bay. Tonight she could not keep them all at bay, for though she was pleased with her adventure and the speculations in which it permitted her to indulge, she was altruistically concerned for the other actors in it, and it would have obvious consequences for herself. Mrs Widdows was not a lady to whom confidences could be made or who would accept excuses, and Hannah would presently find herself without a situation. It was a familiar experience but, in this case, her contempt would have to be assumed, and she made a rapid calculation of her savings, shrugged her shoulders and took a half-turn to the right. A cup of coffee and a bun would strengthen her for the encounter with her employer and, as she sipped and ate, she could pretend, once more, that her appearance belied her purse and that she was one of those odd, rich women who take a pleasure in looking poor. She was good at pretending and she thanked God sincerely that her self-esteem had enabled her to resist the effects of condescension, of the studied kindness which hurts proud spirits, the slyer variety she had encountered, in her youth, from men, when compliance and disdain were equally disastrous to her prosperity, the bullying of people uncertain of their authority, and the heartlessness of those who saw her as a machine set going at their order and unable to stop without another. Her independence had survived all this, and it was, as she knew but could not regret, her conviction of her dignity as a human being which, more than any of her faults, had been her misfortune, but it had its uses when she demanded a bun and a cup of coffee of young women who respected richer appetites, and she went on in this confidence, and with pleasure for though this street might have found itself at home in any city, she knew what lay beyond it and she treated herself as she would have treated a child who thinks it has been cheated of a promise: there was not much further to go, the surprise was close at hand, and when it came she rewarded herself with a long sigh of pleasure.

She stood at the top of a steep hill, lined with shops, edged with lamp-posts, and the shops and the lamp-posts seemed to be running, pell-mell, to the bottom, to meet and lose themselves in the blue mist lying there. Golden and russet trees were growing in the open space which the mist now enwrapped, their branches were spangled with the lights of still more lamps, and though the colours of the trees were hardly perceptible at that distance and in the increasing darkness, Hannah’s memory could reinforce her sight and what she saw was like a fine painted screen for the cathedral of which the dark tower could be seen against a sky which looked pale by contrast. Whether the prospect was as lovely to others as to her she did not know, nor did it matter; the wonder of it was that her childish recollections had not deceived her. She had stood on that spot, for the first time, thirty years ago when, after a day’s shopping, she and her parents had halted for a moment before they made their descent on their way to the station, and the lights, the mist, the trees peering through a magic lake of blue, had been no more fairy-like to her then than they were now. There were things, she told herself, that were imperishable, but she smiled as she remembered how her father had attributed the fairy blue to the damp rising from the river and how her mother had sighed at the downward jolt. For the small Hannah – and she pictured herself in her queer clothes and country-made boots, with her father, gnarled like one of his own apple trees on one side of her, and her mother, as rosy as the apples, on the other – it had been a journey of delight which suffered no diminishment, for no sooner had they reached the blue and lost, in gaining, it, than they turned a corner and were in the midst of a confusion as exciting as a circus, for here huge coloured tram-cars – and Hannah never lost her love for them – were gathered round a large triangle of paving, and when one monster, carefully controlled, glided away to the sound of a bell and the spluttering of sparks overhead, another would take its place, and the first would be seen growing smaller as it gathered speed and swaying in the pleasure of its own strength. There seemed no end to these leviathans, with their insides illuminated as, surely, that of Jonah’s whale had never been, and when she was hustled into one of them, with pushings from both parents, before she had had her fill of gazing, she almost lost a glimpse of the masts and funnels of ships rising, as it seemed, from the street, and though she was to learn that here a river carried in a culvert met the water of the docks, knowledge, which spoils so much, had not deprived the young Hannah, or the mature one, of a recurring astonishment at the sight.

Much had changed in the city since those days. The steep street roared with ascending and purred with descending motor-cars; there were more people on the pavements – where did they come from? Hannah asked, thinking of the declining birth-rate – but she did not resent their presence. A throng of people excited her with its reminder that each separate person had a claim on life, a demand to make of it as imperious as her own, and an obligation towards it, a thought that was both humiliating and enlivening. And she had no miserliness in her pleasures, no feeling that they were increased by being hidden. Involuntarily, she half flung out a hand as though she invited all these strangers to share with her the beauty spread out below, and it was with regret, but a pressing hunger, that she turned into a tea-shop a few paces down the street.

At this hour when it was too early for dinner and too late for tea, the shop was almost empty and a lady who was sitting in full view of the door and who started at Hannah’s entry, immediately repressed all signs of dismay and resigned herself to the impossibility of avoiding recognition. She laid down her knife and fork while Hannah, on her part, advanced with every appearance of enthusiasm.

‘Lilla! What luck!’ she exclaimed loudly, and then chuckled contentedly as her eyes, which were not quite brown, or green, or grey, surveyed all that was visible of the seated figure. ‘Just the same!’ she murmured, and her large, amiable mouth was tilted at the corners. ‘If I’d pictured how you’d look if I met you – but to tell the truth, Lilla, I haven’t been thinking of you lately – I should have imagined you exactly as you are. That hat – so suitably autumnal, but not wintry.’

‘For goodness’ sake, sit down, Hannah, and lower your voice a little. What on earth are you doing here?’

Hannah sat down, and on the chair occupied by Mrs Spenser-Smith’s elegant monogrammed hand-bag, she placed her own shabby one, with a deliberate comparison of their values which made Lilla jerk her head irritably, but there was nothing envious in Hannah’s expression when she looked up.

‘And your coat!’ she went on. ‘It’s wonderful how your tailor eliminates that tell-tale thickness at the back of the middle-aged neck. But perhaps you haven’t got one. Anyhow, you look very nice and it’s a pleasure to see you.’

Mrs Spenser-Smith blinked these compliments aside and remarked, ‘I thought you were in Bradford, or some place of that sort.’

‘Not for years,’ Hannah said, peering across the table at Lilla’s plate. ‘What are you eating? And why? Have you caught the restaurant habit, or haven’t you got a cook?’

‘I’ve had the same cook for more than ten years,’ Mrs Spenser-Smith replied loftily.

‘I call that very creditable,’ Hannah said, beckoning to the waitress and ordering her coffee and bun. ‘I wish you’d ask her how it’s done.’

‘By giving satisfaction,’ Mrs Spenser-Smith replied loftily.

‘And getting it, I suppose,’ Hannah sighed. ‘Oh well! What you get on the swings, you lose on the roundabouts, and I’d rather have my experience than her character, for what, after all, can she do with it, except keep it? And it must be an awful responsibility. Worse than pearls, because you can’t insure it.’

‘On the contrary,’ Mrs Spenser-Smith began, but Hannah held up her hand.

‘I know. I know all the moral maxims. It sounds so easy. But then, all employers are not like you, Lilla. This coffee smells very good, but alas, how small the bun appears! Yes, your servants are well fed, I haven’t a doubt, and I’m sure their bedrooms are beyond reproach. You should see the one I’m occupying now! It’s in the basement, among the beetles. The servant sleeps in the attic, safe from amorous policemen. Don’t frown so anxiously, Lilla. I am obviously in no danger.’ She sat back in her chair and shut her eyes. ‘But I can hear the ships. I can hear the ships as they come hooting up the river. D’you know what nostalgia is? It’s what I was suffering from when, as you put it, I was in “some place of that sort”. So I spent some of my hard-earned—’

‘Don’t shout,’ Mrs Spenser-Smith begged.

‘It doesn’t matter. With your well-known charitable propensities, I shall only be taken for one of your hangers-on – which I may be yet, I warn you. I spent quite a lot of money on Nonconformist religious weeklies, and very nearly reestablished my character by reading them ostentatiously. But it was the advertisements I was after. I wanted to be in Radstowe, and Radstowe, I knew, would proclaim its needs in the religious weeklies. I took the first offer, at a pittance, too late to see the lilacs and laburnums, but in time for what, I’m sure, you call the autumn foliage, Lilla dear. And,’ she added sadly, ‘I shan’t last until next spring and it was the spring I wanted, for tonight, as ever is, I fear I’m going to get the sack.’

Mrs Spenser-Smith frowned again, and after an anxious exploring glance which, happily, lighted on no face she knew, she said sharply, ‘And you sit here, eating cakes!’

Lifting her level eyebrows, Hannah looked with amusement at her plate, where there was a scattering of crumbs. ‘I was always reckless,’ she murmured, and then, with an air of being politely eager to shift the conversation from herself, she asked effusively, ‘And how is Ernest? And how are the children? I should love to see the children!’

‘They’re at school,’ said Mrs Spenser-Smith, promptly putting an end to Hannah’s hopes. ‘Ernest, as usual, is quite well. He overworks, of course,’ she added, between pride and resignation. ‘And now, Hannah, what’s this about losing your situation? And do tell me the truth – if you can. Who are you living with?’

‘A tall, gaunt woman with a false hair-front. Dresses in black – I’m supposed to be mending her second best at this moment. Even her stays are black and they reach from her armpits to her knees. Wears black beads in memory of the departed and has his photograph, enlarged and tinted, on an easel in the drawing-room. Lives in Channing Square, name of Widdows. Prophetic! I suppose that’s why he risked it.’

‘Don’t be vulgar, Hannah. I think jokes about marriage are in the very worst taste. Widdows? I’ve never heard of her.’

‘Perhaps that’s why she’s so unpleasant,’ Miss Mole said gently.

The robin-brightness of Mrs Spenser-Smith’s brown eyes was dimmed with disapproval. She was not stupid, though she chose to let Hannah think her so, and she said severely, ‘According to you, Hannah, every employer you’ve ever had was objectionable.’

‘Not all,’ Hannah said quickly, ‘but naturally, the ones I loved I lost – through no fault of my own. They were exceptional people. The others? Yes, what can you expect? It’s the what-d’you-call-it of the position, and perhaps – it’s a long chance but perhaps – there are people who find Mrs Widdows lovable.’

‘You don’t adapt yourself,’ Mrs Spenser-Smith complained. ‘It was the same at school. You were always kicking against authority. But you ought to have learnt sense by this time and if you leave this Mrs Widdows, what are you going to do?’

‘I don’t know,’ said Miss Mole, ‘but I really think I’ll have another bun. I’ve got a spare twopence-halfpenny in my pocket. I earned it – by sleight-of-hand. Yes, another of those excellent buns, please, and a curranty one. Doctors,’ she informed Mrs Spenser-Smith, ‘tell us that currants have sustaining properties, and I badly need them. I don’t know what I’m going to do and I’m not worrying about it much. I’ve got a whole month for making plans and I always enjoy the month I’m under notice. I feel so free and jolly, and there have been occasions when I’ve been asked to stay on, after all. Happiness,’ she said, a slight oiliness in her tone, ‘is a great power for good, is it not?’

‘Tut!’ said Mrs Spenser-Smith. ‘Don’t try any of that with me! I know you too well.’

Miss Mole chuckled, ‘But not so very well – in Radstowe. I’ve been careful of your reputation. I haven’t told a soul that we’re related. I didn’t even put you to the inconvenience of letting you know I was here. You should give me credit for that. And if I’d said I was the cousin, once removed, of Mrs Spenser-Smith, that old black cat might have been different, for, of course, everybody knows who you are! But there, I never think of myself!’

‘If you’d been entirely penniless, it would have been much better for you,’ Lilla pronounced distinctly. ‘I suppose that house of yours is let?’

‘House?’ said Hannah. ‘Oh, you mean my teeny-weeny cottage.’

‘You get the rent from that, don’t you?’

‘I suppose so,’ Hannah said, smiling oddly, ‘but really, my money has such a trick of slipping through my fingers—’

‘Then you can’t go there, when you leave your situation. You’d better eat humble pie, Hannah, for what’s to become of you I don’t know.’

‘Well,’ said Miss Mole in a drawl, ‘it’s just possible that I might find myself in your nice red and white house, and no later than tomorrow, for I may be dismissed without warning. In your nice house, behind the lace curtains and the geraniums and the gravel sweep, having my breakfast in bed, though I’m afraid my calico night-gowns might shock your housemaid.’

‘I wear calico ones myself,’ said Mrs Spenser-Smith, putting the seal of her approval on them.

‘But I don’t suppose your housemaid does.’

‘And breakfast in bed is not what you want, Hannah.’

‘That’s all you know about it,’ Hannah said.

‘What you want,’ Lilla continued, ‘is a place where you’ll settle down and be useful, and if you’re useful you’ll be happy. Now, can’t you make up your mind to please this Mrs Widdows?’

‘She doesn’t want to be pleased. She’s been longing for the moment when she could turn me out and find another victim, and now she’s got it. And I’m not afraid of starving while I have a kind, rich cousin like you, dear. And an old school-fellow, too! What I want at my age, which is your own, is a little light work. In a house like yours, you can surely offer me that. You must want someone to arrange the flowers and sew the buttons on your gloves, and I shouldn’t expect to appear at dinner when there’s company. You wouldn’t have to consider my feelings, because I haven’t got any, and if the cook gave notice, I could cook, and if the parlourmaid gave notice, I should be tripping round the damask.’

‘Yes, I daresay! And spilling the gravy on it! And, as it happens, my servants don’t give notice. At the first sign of discontent, they’re told to go.’

‘That’s the way to treat them!’ Hannah cried encouragingly. ‘But if they fell ill, Lilla,’ – she leant forward coaxingly, ‘think what a comfort I should be to you! And you know, Ernest had always a soft spot in his heart for me.’

‘Yes,’ said Lilla, ‘Ernest’s soft spots are often highly inconvenient. Today, for instance, when I wanted the car to take me home after a busy afternoon, he chooses to lend it to someone else. I have to be at the chapel this evening for the Literary Society Meeting and I should be worn out if I made two journeys across the Downs beforehand.’

‘Good for your figure,’ Hannah said. ‘The time may come when your tailor won’t be able to cope with it. So that’s why you’re dining out. I should like to see you at the Literary Meeting, trying not to yawn. What’s the subject?’

‘Charles Lamb.’

‘Hardy annual,’ Hannah muttered, twitching her nose.

‘It’s a duty,’ Mrs Spenser-Smith said patiently, yet with a touch of grandeur. ‘I’d much rather stay at home with a nice book, but these things have to be supported, for the sake of the young people.’

‘Ah yes, but it isn’t the young people who go to them. It’s the old girls, like myself, who have nothing else to do. I’ve seen them, sitting on the hard benches, half asleep, like fowls gone to roost.’

‘They’ll go to sleep tonight,’ Lilla admitted, ‘though,’ she added as she remembered to keep Hannah in her place, ‘I don’t see why you should try to be funny at their expense. Trying to be funny is one of your failings.’

Miss Mole answered meekly. ‘I know I ought never to see a joke unless my superiors make one, and then I’ve got to be convulsed with admiring merriment. I’ve no right to a will nor an opinion of my own, but somehow – I’m that contrary! – I insist on laughing when I’m amused and exercising my poor intelligence. Let me come with you tonight, Lilla, and I might make a speech.’

‘You might make a fool of yourself,’ said Mrs Spenser-Smith, picking up her modestly rich fur necklet and settling it at her throat. ‘Go back to Channing Square, at once, and do, for goodness’ sake, try to see which side your bread is buttered. And, in any case, Mr Blenkinsop’s lecture wouldn’t entertain you. He’s rather a dull young man. What’s the matter?’ she asked, for Hannah had put down the bun she was lifting towards her mouth and the mouth remained open. ‘Such a funny name!’ Hannah murmured. She leaned back and folded her hands on her lap. ‘I like to co-ordinate – or whatever the word is – my impressions with other people’s facts. Now, that name. I should have suspected its owner of being a dull young man, a rather owlish young man, with a Biblical Christian name. Am I right?’

‘His name is Samuel,’ said Mrs Spenser-Smith, impatient with this topic.

‘And he’s a member of your chapel?’

‘Not a very worthy one, I’m sorry to say. He’s highly irregular.’

Now Hannah leaned forward, her eyes sparkling. ‘You’re not going to tell me he’s a bit of a rake?’

The droop of Mrs Spenser-Smith’s eyelids effaced a world which had any acquaintance with rakes. ‘Irregular in his attendance on Sundays,’ she said coldly.

‘That upsets one of my theories, but it’s interesting. Are you going, Lilla? Try to find a corner for me in your red and white house. I’ve been past it several times. I like the colour scheme. The conjunction of the yellow gravel with the geraniums—’

‘The geraniums are over,’ Lilla said, ‘and what colour do you expect gravel to be? I shall ask Ernest if he knows of any suitable post for you.’

‘Ernest’s reply will be obvious. You’d better not ask him.’

‘And then I’ll write to you.’

‘Don’t bother, don’t bother,’ Miss Mole said airily. ‘I’ll come to tea one afternoon. These,’ she smiled maliciously, ‘are not my best clothes – but very nearly. My shoes, however,’ she thrust out a surprisingly elegant fo. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...