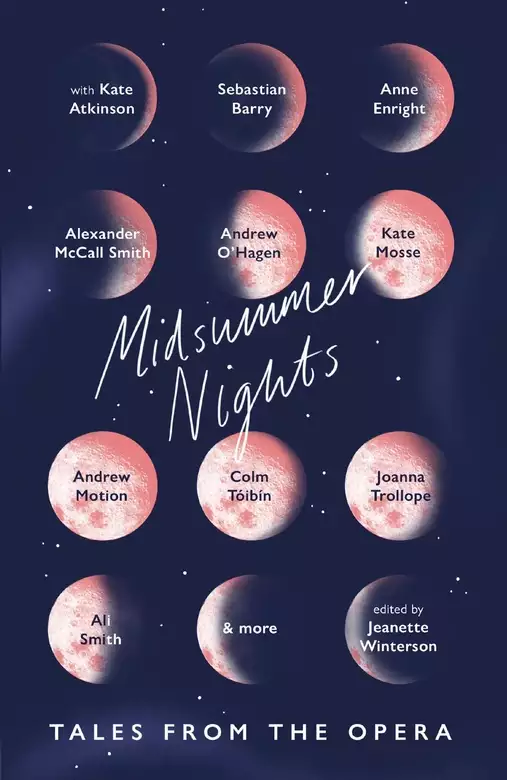

Midsummer Nights: Tales from the Opera:

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

With Kate Atkinson, Sebastian Barry, Anne Enright, Alexander McCall Smith, Andrew O'Hagan, Kate Mosse, Andrew Motion, Colm Tóibín, Joanna Trollope, Ali Smith, Jeanette Winterson & more In this stunning collection, the best and brightest writers working today reimagine familiar stories from the greatest operas. Don Giovanni's ghost haunts a young boy, Fidelio meets Porgy and Bess and two hapless men stage a Mozartian love test. Long-lost loves enter the dating game and undying witches finally get grey hairs. Funny, macabre or irreverent, these stories are charming for any opera lover and a beguiling collection in their own right.

Release date: April 18, 2019

Publisher: RiverRun

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Midsummer Nights: Tales from the Opera:

Jeanette Winterson

This ebook edition first published in 2019 by

An imprint of

Quercus Editions Ltd

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

An Hachette UK company

Collection and introduction copyright © 2009 by Jeanette Winterson

‘First Lady of Song’ © 2009 by Jackie Kay, ‘Fidelio and Bess’ © 2008 by Ali Smith, ‘Freedom’ © 2009 by Sebastian Barry, ‘To Die For’ © 2009 by Kate Atkinson, ‘The Growler’ © 2009 by Julie Myerson, ‘The Ghost’ © 2008 by Toby Litt, ‘Nemo’ © 2009 by Joanna Trollope, ‘The Pearl Fishers’ © 2008 by Colm Tóibín, ‘Key Note’ © 2009 by Anne Enright, ‘First Snow’ © 2009 by Andrew O’Hagan, ‘Goldrush Girl’ © 2009 by Jeanette Winterson, ‘The Martyr’ © 2009 by Ruth Rendell, ‘String and Air’ © 2009 by Lynne Truss, ‘The Empty Seat’ © 2009 by Paul Bailey, ‘My Lovely Countess’ © 2009 by Antonia Fraser, ‘La Fille de Mélisande’ © 2009 by Kate Mosse, ‘Now the Great Bear…’ © 2009 by Andrew Motion, ‘Forget My Fate’ © 2009 by Marina Warner, ‘The Albanians’ © 2009 by Alexander McCall Smith

“BLUE MOON” (Hart/Rogers) © 1934 EMI Robins Catalogue.

Administered by J. Albert & Son Pty Limited. Used with permission

BLUE MOON

Music by RICHARD RODGERS Lyrics by LORENZ HART

© 1934 (Renewed) METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER INC.

All Rights Controlled and Administered by EMI ROBBINS CATALOG INC.

(Publishing) and ALFRED PUBLISHING CO., INC. (Print)

All Rights Reserved Used by permission from ALFRED PUBLISHING CO., INC

The moral right of Jeanette Winterson to be identified as the editor of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing

from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 52940 406 7

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations,

places and events are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used

fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales

is entirely coincidental.

Cover design © 2019 Andrew Smith

www.riverrun.co.uk

Introduction

Jeanette Winterson

Opera has always needed a story. Some inspirations are direct – like Britten’s Turn of the Screw, or Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, and others, like Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro, or Verdi’s Rigoletto, take a story and shift it.

Why not take an opera and shift it?

All the stories in this collection have done exactly that; found a piece of music and worked it into a new shape. It doesn’t matter whether the reader knows the source or not – the stories are wonderful in their own right – but those who do know the operas will get an extra twist of pleasure from peering into the forge where they were made.

The brief to each writer was simple: choose an opera, and from its music or its characters, its plot or its libretto, or even a mood evoked, write a story.

Glyndebourne is one of the most innovative opera houses in the world, and for that reason a collection of new stories to celebrate its seventy-fifth birthday seemed like a tribute to its remarkable past and a flare sent up towards the future.

The music began in 1934, after a rather shy John Christie had met the rather sparkling Audrey Mildmay, an opera singer. They had fallen in love, and as Christie happened to have a stately home, he offered it as a love-gift to his wife. They would start an opera house together, get a few Members to subscribe, put on The Marriage of Figaro…

The thing ran on rather a small scale at first, then it was interrupted by the War, but at the end of the War, Glyndebourne decided to reopen with a new commission – the young Benjamin Britten’s Rape of Lucretia, with Kathleen Ferrier in the title role.

Brave or what? Just when everyone longed for the familiar and the known, for straightforward entertainments and light relief, Glyndebourne backed a young man writing a new opera, and did so to reaffirm culture as necessary to a civilized life.

This was no grand gesture, no posturing – it was a simple and heartfelt belief in music and its emotional power, in art as a force for good.

Seventy-five years later, still in the Christie family, and running without public subsidy, Glyndebourne offers world-class opera every year from May until August, and continues to support new work, and to stage some of the more difficult or less easily understood operas, as well as the core rep.

I think that Glyndebourne is a place where people can find opera for the first time, and fall in love with it. I think it is a place that has kept its values. Yes, some tickets cost a fortune, but some don’t, and whether you dine in style or eat sardine sandwiches on the lawn, the music is what matters.

*

That opera is a necessary synthesis of words and music makes it so potent. The stories in this collection have the music in them. The rhythm, breath, movement of language, like music, creates emotional situations not dependent on meaning. The meaning is there, but the working of the language itself, separate from its message, allows the brain to make connections that bypass sense. This makes for an experience where there is the satisfaction of meaning but also something deeper, stranger. This deeper stranger place is an antidote to so much of life that is lived on the surface alone. When we read, when we listen to music, when we immerse ourselves in the flow of an opera, we go underneath the surface of life. Like going underwater the noise stops, and we concentrate differently.

These stories are quite different from each other, and absorbing in unexpected ways. What they share is the music, and what I hope they will prompt is a curiosity about music, in particular, opera, among readers who might think that opera is not for them. Story lovers who are also opera lovers will delight in the inventions, and be moved, I hope, by the richness of these collisions between words and music.

In the end it is all about feeling. I think we spend quite a lot of time trying to control our feelings, only to find ourselves hopelessly overwhelmed when we least expect, or least want it to happen.

For me, opera is a place where all the emotions can be fully felt yet safely contained. Certainly this has therapeutic value, but art is not therapy – at least not principally so: it is a profound engagement with life itself, in all its messiness, its glory, its fear, its possibility, its longing, its love.

And these stories here, funny, sad, wise, true, reflective, speculative, ardent, each with its own tempo and written in its own key, are ways to think, and ways to feel.

And there’s Posy in the middle, drawing us in, reminding us that we are part of the picture, as well as part of the song.

First Lady of Song

Jackie Kay

My father wasn’t thinking of me when he kept me alive for years. I was my father’s experiment. At the end of this long life, when my skin is starting to show its age, finally, and my hair has the shy beginnings of grey, I need to speak. I’ve got out of the way of talking. It’s so much easier to sing, Da dee dee dee di deeeee. Talking, I always trip myself up, make some nasty mistake. It’s had the effect of people thinking of me as crazy, doo- lah- li- lal. I’ve learnt to talk lightly about things, just skimming the surface, in case I found myself in trouble. It is difficult to know where to begin – doh ray me fah so lah ti doh – for me there was no real beginning. I knew nothing of what was happening to me. One day, I was my old self, those years ago, carefree, spontaneous, and loving; another day, those qualities had gone. When I was first drugged, I fell into a coma, apparently. I was in that coma for a week; my father told me when I came round. He seemed delighted about my coma, he smiled, patted my head, and said, ‘I think it’s worked; it’s a miracle.’ I fled. I left my father, my mother, my sisters and brothers. I never looked back, and he never found me. Back in those early days, I had a different name. My name was Elina Makropulos. I’ve had many husbands, countless children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren. Some of my children are a blur, but the pianos are vivid – the babies and the uprights, the ebony and ivory, the little Joes.

I remember time through music – what I was singing when. How I loved those Moravian folk songs, how I lost myself in those twelve-bar blues, how I felt understood by those soaring arias, how beautiful ballads kept me company, how scatting made me feel high. For years I’ve been singing my head off, singing my head off for years. When I sang Elina’s head off, Eugenia came. When I sang Eugenia’s head off Ekateriana came. When I sang Ekateriana’s arias, Elisabeth came. After Elisabeth I was Ella. My favourite period was my Ella period. Every song I sang had my own private meanings: ‘I didn’t mean a word I said’, ‘Into each life some rain must fall’, ‘Until the real thing comes along’, and even ‘Paper Moon’. I’d lived so long, nothing was real. Ella seemed to be cool about that. Bebop, doowop! Eeeeee deee dee dee dee de oooooooooh dahdadadada bepop doowop brump bum bump.

Now, I’m Emilia Marty. I’m in the middle of being Emilia Marty. I’ve returned to being a classical singer, my first love. My voice is deeper now. I’ve sung about every type of love through all the years. Back in those early years when I was Elina Makropoulos, my skin was pale, perhaps a little translucent. As the years went on, I got darker and darker. Now, my skin is dark black. Emilia Marty has dark black skin. I’m rather in awe of it. It is not transparent, it is not translucent, but it is shimmering. I wear a great dark skin now, like a dark lake, like a lake at night with a full moon in the sky. Way back in the days when my father first drugged me, I remember seeing the last moon I ever saw as Elina Makropoulos; the last moon before I fell into a coma. It was a new baby moon, rocking in its little hammock, soft-skinned, fresh. Or it was the paw of a baby polar bear, clawing at the sky. Or it was a silver fish leaping through the voyage of the deep, dark sea-sky. That’s the only other thing that’s accompanied me on my long journey, the moon. The moon has never been boring! I wrote a song for it back in my Ella days: Blue Moon, I saw you standing alone.

I’ve been lonely with my lies for years. I told none of my many children the truth about their mother. I didn’t want them to carry the burden. I wanted them to think that they had an ordinary mother who looked good for her years, who was pretty healthy perhaps. Every time, I ran into an old friend or acquaintance who said, ‘It’s remarkable, you haven’t changed a bit,’ I smiled grimly and knew that they were telling the absolute truth. None of them knew that it was the truth, or how uncanny their little clichés were for me. ‘You don’t look a day older than the last time I saw you’, ‘Your skin hasn’t got a single line’, ‘You’re incredibly youthful-looking’. All were sickening sentences for me. The only change for me was my skin gradually darkening, yet nobody noticed this. Nobody lived long enough!

I’d sing my children lullabies, and chortle to myself when I got to Your daddy’s rich and your ma is good-looking knowing full well that daddy would die first and so would baby, and that the person who should really want to cry was me – Hush Hush, little baby. When nobody knows who you truly are, what’s the point in living? We’re not alive to be alone on the planet. We’re alive to share, to eat together and love together and laugh together and cry together. If you can never love because you will always lose, what reason is there to live? I have lost husbands, daughters, and sons. When my father used me as his experiment I don’t imagine he ever thought properly about the life of grief he was consigning me to, the grief, handed down the long line of years, a soft grey bundle of it. After a while, I stopped loving anyone so that I wouldn’t be hurt by their death. If you are certainly going to outlive all your family and your friends, who keeps you company? Only the songs knew me – only the songs – the daylight and the dark, the night and the day. Some songs lasted longer than sons. Some ballads outlived my daughters. Some lieder survived my lovers. Some folk songs lived longer than my folks, Fahlahdiddleday. Perhaps he might have thought of it as a gift. There is no way for me to go back and unpick the years to find out what my father hoped for me. The truth is more uncomfortable, I think. He didn’t consider me in the equation. I was his experiment. He didn’t know if it would work or not. Even now, all this time away, I can’t stop myself from wondering about this. I cannot fathom my father.

*

I have not loved for so many years, I can’t really be sure of the sensation of it, how it feels, if it is good or if it is frightening. If it is deep, how deep it goes, to which parts of the body and the mind? I have no real idea. My biggest achievement was getting rid of it altogether! What a relief! I remember that. The sensation of it! The day that I discovered I could no longer love. It was like a lovely breeze on a hot day. It billowed and felt really quite fine. I remember when, some time ago, I stood, a young woman at the grave of my old son, and not a tear came. I said to myself, ‘He was tone-deaf that one, he could never sing,’ and laughed later that night, drinking a big goblet of wine. Years later, I remember being at the funeral of my old daughter, a vicious tongue she had, that one, I said to myself and threw the rose in. So, Goodbye dear. I tried to remember if I had ever taken pleasure in any of her childhood, in reading her a book, or holding her small hand, or buying her a wooden doll. And though I had done those things, I think, I could not remember getting any pleasure. I could not remember getting anything at all.

People would say that I was the world’s greatest singer, back when I was Ella, I had a vocal range spanning three octaves and a pure tone, my dear. They said on the one hand I seemed to feel and know everything and on the other, I had never grown up. (True, true!) I could sing the greatest love songs and yet appear as if nothing touched me, as if I’d never had sex. Nobody but myself knew the irony in the way I sang Gershwin’s The way you wear your hat, the way you sip your tea, the memory of all that, no, no, they can’t take that away from me. I sang it defiantly, despite the fact that they were taking it away from me all the time, and one husband’s hat frankly had blended into another’s and I barely noticed the way they sipped their tea, let alone remembered it. When I sang Cole Porter’s I’ve got you under my skin, myself, to Elina, Eugenia, Ekateriana, Elisabeth, I was trying to keep myself together.

I had sex over and over again. Sometimes I’d get lost in it; sometimes it was the only thing that could go right through me, where I could banish the lonely feeling and abandon myself to somebody else, the soft skin of an earlobe, anybody’s earlobe, the smell of morning breath, the hair on a chest. For a moment, any little intimacy would make me feel I was standing on a smallholding, and not out in the vast, yellow, empty plains, the wind roaring on my face, singing my plainsong. I barely remember some of my men; the love songs lasted way longer than the lovers. Some were large and some were small, but all seemed to be fertile, alas. And when child came out after child, between my legs and over the centuries, I would gaze down in a sort of trance, a huge boredom coming over me already, before the new baby even suckled on my breast. Another baby! So what! Another baby to feed and teach to read and count and watch die. I lost my children to typhus, whooping cough, scarlet fever, tuberculosis, cholera, smallpox, influenza. Many of my children died before they were ten or fifteen. I remember a couple of hundred years ago looking wistfully at my daughter Emily, and wishing on the bone of the hard white moon that I could catch her whooping cough and die, die, die. It was never for me, death, never going to be handed out to me on a lovely silver platter, not the gurgle or the snap or the thud or the whack or the slide of it, death. No. I was consigned to listening to the peal of church bells barely change over the stretch of years.

When I came to be Ella, I was so much more independent. Those were plucky, scatting days. Even the moon bopped in the sky. I was on the road forty out of forty-five weeks. I’d come a long way. I’d gone from working with dodgy numbers runners to being the first African-American to perform at the Mocambo! Life takes odd turns. In my case, lives take odd turns. There I was finally as integrated as Elvis, singing songs by Jewish lyricists to white America, having folk like Marilyn Monroe fight in my corner. Every time I sang Every time I say goodbye I felt it more than people knew. I was saying goodbye all my life. I was saying goodbye to my other selves, Elina, Eugenia, Ekateriana, Elisabeth, Ella. My own names were a kind of litany. Only the songs knew my secrets, only the music was complex enough to contain me. When I was Elisabeth, I was known for how I sang Strauss’ Four Last Songs. One time, late in my Elisabeth day, I was performing at the Albert Hall, singing Straussy for the umpteenth time and I got to the last stanza. I felt like him; I welcomed death. I sang with true feeling – O vast tranquil peace, so deep at sunset, how weary we are of wandering, is this perhaps death? One of the reviewers said I’d grown into the songs over the years. Well, yes.

There’s been so much to grow into over the years. I’m like an old person the way I pick out memories and cluck over them. Well, they say the old repeat themselves and the young have nothing to say. The boredom is mutual! I’ve got an old woman’s head in a young woman’s body. Thank you for the memories! I remember: my excitement when I first got to fly on an aeroplane, getting adjusted to the phone and its ring, having penicillin suddenly for my children, my first X-ray, how my hair felt the first time it was blow-dried, how exciting the indoor bath with running water, how bamboozling the supermarket was at first. There was nobody around who’d lived as long as me, nobody to say, I liked it before we had supermarkets, I liked it before zoos arrived, before we had aeroplanes, before the hole in the ozone, I liked living before all those things. I didn’t like the poverty, the sickness, but there is still something to be said for a good cobbler, an honest loaf of bread, a cobbled street, bare oak beams, revolution. Even the words for everything have kept changing over the centuries. I’ve had to keep up with the Vocab. Jeepers Creepers. I’ve had to keep changing my talk. I’ve lived long enough to see bourgeois go out and bespoke come in.

I took a boat trip down the Vltava river in Prague, many moons ago. The food in Prague – how I loved breast of duck with saffron apples, how I loved my mother’s flaky apple strudel. I remember the first time I ate a sandwich in England and even when the word sandwich came in. My favourite pie ever was way back in the nineteenth century. They don’t make them like that these days! It was filled with chicken, partridge and duck and had a layer of green pistachios in the middle. I don’t remember who I was then, but I remember that pie! I remember when tea and coffee and sugar started being so popular. I remember my first drink of aerated water, ginger ale. I used to have a lovely silver spirit kettle. I remember the excitement of my first flask, how I took it on a lavish picnic. All musicians love a picnic, always have. There’s always been music and wine, concerts and hot puddings, strawberries, champagne. Food and Claret and Ale all seemed to taste better a while back. As I’ve gone through times, I’ve noticed so much getting watered down. Not just taste, but ideas. Oh for the fervour and passion of Marx now. Oh for the precociousness of Pascal. Oh the originality of Picasso.

My body never changed shape or height, give or take an inch or so. It was my colour that changed, and with my colour my voice. My voice is deeper now; if it was a colour it would be maroon. I’ve returned to singing the spirituals that I sang back in the days when I was another self. Swing low sweet chariot, coming forth to carry me home, swing low sweet chariot, coming forth to carry me home. There is a balm in Gilead to make the wounded whole. There is a balm in Gilead to heal the sin-sick soul. My voice is deeper than I could have ever believed when I was a soprano. I go low, Go down Moses, till my voice is at the bottom of the river bed, with the river reeds and marshes.

I look at myself in the mirror. My skin is still young-looking, and a dark blue-black colour. I look about thirty when I’m really three hundred years old. I’ve looked about thirty all these years. These days, it’s easier for me to make up my face, to add a little lipstick, a little blusher, and mascara for my already very long eyelashes. My eyelashes have grown over the centuries and are now a lavish length. People comment on them. ‘I’ve never seen such long eyelashes,’ they’ll say and I roll my eyes. I’ve been here a long time. There is nothing new under the sun that anyone can say. I’ve lost the ability to be surprised – which is worse I’ve discovered than losing the ability to surprise. Nothing about myself interests me. I’ve lost all vanity, so compliments are dreary. I’ve lost my passion for ideas, so conversations trap and unnerve me. I’ve lost my love of listening to the way that people talk, because I’ve found, over the years, people say more or less the same thing, and expect me to be riveted – the price of food, the price of fuel, the children, the schooling, the illness, the betrayal, the blow, the shock. Specific times and events jump out at me – I remember when the abolition of the triangular slave trade was announced; when women first got the vote; when Kennedy was assassinated, when segregation and Jim Crow laws started to change. Actually, I really thought something might change properly in the Nineteen Sixties. That was the last time I felt optimistic. I’ve lived through so much hurt, so many wars, so much hunger, so much unkindness and cruelty. At last, it seemed to me a decade that people cared, and the talk was interesting and I buzzed and sang and actually made some friends. And the friends I made seemed to care about me, and we all had pretty good sex with each other, sometimes three or four of us at the same time. It was liberating until it became narrow and selfish, and petty jealousies and concern about money started creeping in, and all those lovely Sixties flower folk seemed to wake up and say, I want I want I want. And off they went, the marchers, protesters, petitioners, to see acupuncturists, therapists, homeopaths. So I crept off, changing my name again and my skin darkened. I bumped into one of my old friends twenty or so years later – I lose all track of time – and she had a bungalow, three kids, a garage, a drinks cabinet, a mortgage, a pension, a car and a broken heart. Her husband had gone running off with someone half her age. She looked at me wistfully and said, ‘Oh but Emmy you haven’t aged at all. It’s quite incredible. You look exactly the same as the day I last saw you.’ She stared at me, and looked worried. She was the first person that ever really knew in her bones that something was not right with me.

She invited me round to her house a few weeks later. What have you been doing, Emmy, did you get married, have children? she said. I laughed, and told her the truth. I thought what have I got to lose? I’ve been alive for three hundred years, I said, and she exploded laughing. ‘Emmy,’ she snorted, ‘you always were so droll!’ ‘Children?’ I laughed, ‘I’ve had children, many, many children, and outlived the lot of them. Husbands? I’ve had husbands over the centuries, and buried them all.’ The tears were pouring down my innocent friend’s face by now. ‘What have I been doing?’ I asked her back rhetorically. ‘I’ve seen kings and queens come and go. I’ve seen governments rise and fall. I used to have sympathy for the Whigs. I’ve lived in Czechoslovakia, America, England.’ My friend’s eyes glazed over. Suddenly, I wasn’t funny, I was boring. She yawned. ‘You’re tired?’ I asked, gathering speed. ‘I’m exhausted. Imagine how tired you would be if you were three hundred years old.’ ‘Would you like a big gin?’ she asked eagerly, desperate to change the subject. ‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Why the hell not after all the things I’ve seen? What about you?’ I asked her. The rest of the evening was spent on the h. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...