ONE

The Big Move

I'll never forgive my mother for naming me Milagro.

"Milagro!" she would yell. "Come down to dinner," "Do your homework," "Put that book down and get ready for the ambassador's dinner." I always said I'd do whatever she asked if she would only call me Mila or, even better, Jenny, which wasn't my name at all. At least Mila sounded like an actual girl's name, but my mother, Maggie (not short for Margaret, so I couldn't retaliate), wouldn't listen. She may have been a successful diplomat, but she was never one for compromise. Her stance on moving away right before my senior year of high school would prove no different. She wouldn't even consider letting me stay behind in Washington, D.C., where we'd lived for four years, the longest I'd ever stayed in one place.

I may have hated the name Milagro, but I knew why my mother chose it. After getting her degree in foreign languages at Berkeley in the early seventies, she moved back to L.A. to live with her parents. One month later, after thirty years of marriage, her cardiologist father left her mother for a Thai waitress just a year older than my mother, who was twenty-three at the time. He never apologized or explained, and my grandmother allowed noone to bring it up.

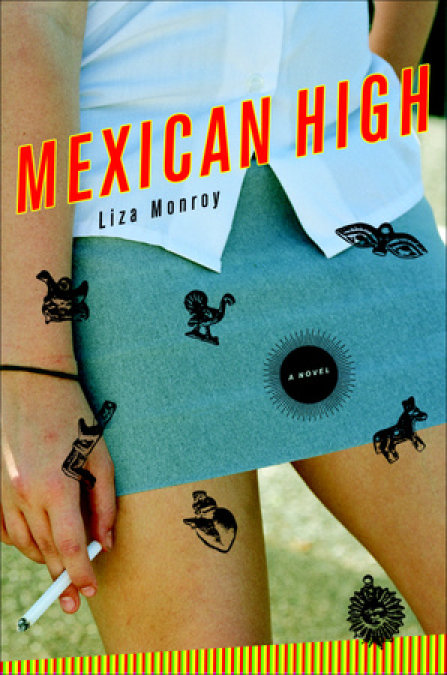

My mother dealt with her family's derailment in the only way she knew how: by taking off. She sold her car, quit her job at the farmers' market, and climbed onto a bus from Los Angeles to Tijuana. She had studied Spanish since high school, and by the time she'd drifted farther south to Mayan territory, she was fluent. She rented a room by the beach in Playa del Carmen, a town on the Mayan Riviera where expatriate types flocked for sun, beautiful beaches, and bohemian lifestyles. To earn enough money to support what soon became a traveling habit, she apprenticed with a jeweler and was soon making her own necklaces, earrings, bracelets, and rings, using unique Mexican charms called milagros, the Spanish word for miracles and surprises. The little bronze and silver eyes, crosses, hearts, fish, and houses were said to bring luck for whatever they represented. An arm stood for strength, a leg for travel. The mule brought fortune in work. Tiny kneeling saints answered prayers.

The milagros might have been responsible for my entire existence: Maggie was supposed to be infertile, having been given a diagnosis of premature ovarian failure as a teenager. So the biggest miracle-and-surprise was when she found out that she was constantly vomiting not from untreated Mexican vegetables or bad tap water but from pregnancy. When she told her best friend, Estela, a local Mayan girl with a thick black braid whose father was the town shaman, Estela pointed straight to my mother's milagro necklace. Since discovering the charms, my mother always wore a string of her favorites around her neck.

"Isn't this something you wanted?" Estela asked, seeming confused.

"Why would you say that?" Maggie said.

"You're wearing the hen, a sign of fertility, right here. And this one"--Estela took a tiny silver child between her thumb and forefinger--"means the wearer asks the saints for a baby girl."

"But it's physically impossible for me to get pregnant," Maggie said. "I've known for years."

"Milagros," said her friend, "work to bring about miracles. What did you think they were for?"

"Estela, what I think is that the doctor in America was wrong."

"You gringas," said Estela, smiling and shaking her head. I imagine she paused for a moment before the obvious question dawned on her. "Magita! Who is the father?"

The randomness of my conception always made me wonder if maybe Maggie, with her wild, free spirit, long flowing hair, and complete self-obsession, perhaps wasn't built for motherhood in the first place--and I'm not talking ovaries. Half globe-wandering hippie, half glamour girl, she was upper-middle-class L.A. breeding meets nomadic adventuress, with a romantic ideal of what a jet-set life might be. But for some reason that I suspect had to do with not being a statuesque, leggy blonde, international playboys weren't exactly inviting her to coast the French Riviera on their private yachts.

***

Maggie sold the milagros on the beach until right before I was born. Then she went back to her mother's house in West L.A., where the streets were all named after rural states: Montana, Nebraska, Iowa. She was only twenty-five. Three months later, she took an administrative job at the Mexican consulate, and sold my grandmother's prized Brandywine heirloom tomatoes at the farmers' market on weekends. One day at work, she heard that U.S. Foreign Service recruiting officers were coming through town looking to hire more women. She decided to take the exam that could grant her entrance into a whirlwind life in far-off places on diplomatic assignments. She passed, and a few months later we left L.A. for good. I was barely two years old.

My life became a blur of ever-changing cultures after that. My mother's job made us country-hoppers, gypsy vagabonds who came and went with the wind. When I landed in D.C. after Shanghai, Guadalajara, Bolivia, Rome, Oslo, and Prague (in that order), I decided I'd make more sense as a person if I had an accent, but there was nothing I could do about that--I spoke perfectly American-sounding English.

As for my father, I'd never met him, but my mother admitted that he was Mexican, married, and that she'd had an unexpected one-night stand with him that summer in Playa del Carmen. She wouldn't tell me his name, or anything else about him; she even said she invented my last name, Marquez, simply because she liked the way it sounded.

"Milagro Epstein didn't sound good," she'd said. Maggie was all about keeping everything as harmonious as possible, even when that was impossible.

Still, I must have resembled the man, whoever he was. My mother had olive-toned skin and eyes so dark you could barely tell the iris from the pupil. She was the one who looked Mexican, not I. I had green eyes, a color people often mistook for the effects of colored contact lenses. My hair was naturally dark blond, lighter in the summer. Everyone always seemed surprised when I introduced myself as Mila Marquez.

"You're really Hispanic? You have that all-American girl-next-door look," said my best friend, Nora, a petite but enviably curvy half-French, half-African girl. We became close our freshman year in D.C., when Nora had the locker right next to mine at our Georgetown high school, which was mostly made up of international students. Her father was the Kenyan ambassador.

"It's true," I said, clasping my lock shut and spinning the dial. "I must be the only blond Mexican ever." Only when we arrived in Mexico City, four months before my seventeenth birthday, did I find out that I was but one of a million light-haired, pale-skinned Mexican girls, and they all seemed to go to ISM, the International School of Mexico.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved