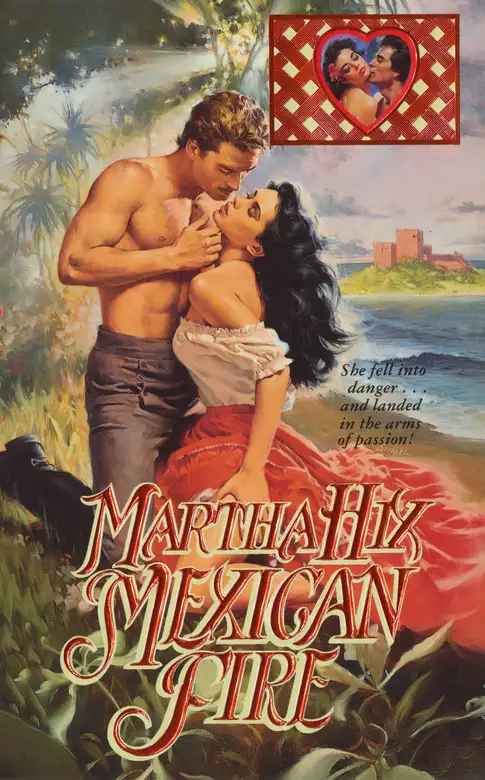

Mexican Fire

- eBook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

HE DESPISED HIM As her beloved Mexico teetered on the brink of overthrow by the ruthless dictator Santa Anna, beautiful Alejandra Sierra schemed with her countrymen to defeat him. They needed a spy from his ranks, and who better than Texas soldier-of-fortune, Reece Montgomery? It was Alejandra's job to "charm" the arrogant, flaxen-haired Reece into helping their cause -- a job she despised, for he was an unscrupulous traitor, loyal only to gold. But when she felt the fire in his soul and the hunger in his kisses, Alejandra found herself cursing her own seduction -- and her own burning need for his masterful touch. HE ADORED HER Reece Montgomery had his own private reasons for being on General Santa Anna's payroll. Still, he didn't trust the general, and he'd bet the raven-haired beauty who'd come to bribe and seduce him was part of some elaborate trap. Well, Reece didn't plan on falling for it ... but then he didn't plan on Alejandra's lips being sweeter than a warm Gulf breeze, or her green eyes promising more passion than an erupting volcano. He would not trust her motives, yet he could not deny his blazing desire to bury himself in her fiery Mexican passion!

Release date: October 1, 1991

Publisher: Zebra Books

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Mexican Fire

Martha Hix

As it had for two centuries, the islet fortress of San Juan de Ulúa overlooked the bay’s black sands and the city’s high walls. Sea gulls cawed and dipped. Inside the town gates, and only a block from the pier, meat and fowl hung in market stalls while odors—shellfish, tortillas, chiles, citrus, mildew—permeated the tropical air.

Even the mood seemed commonplace. The evocative strains of marimba music beat through el mercado. Vendors pestered shoppers. Children shouted and played; lovers strolled around the palm and almond trees; a wife harangued her husband when his wandering eyes strayed to a beautiful señorita. A sultry breeze, warm as the nearby Gulf of Mexico’s waters, ruffled the black mantilla covering an especially beautiful young woman’s dark hair as she alighted from her carriage and headed toward Café Plantain to meet with her Federalist friend Erasmo de Guzman.

She was Alejandra Toussaint Sierra, mistress of one of the region’s largest coffee plantations, Campos de Palmas. Rarely did her lips ease into one of her once ready smiles. Her hazel eyes no longer sparkled. It was broadly whispered her seriousness resulted from a foreign education. That was partially true. For the last three of her twenty-two years she had lived with sorrow having nothing to do with passing from a wild child into a solemn woman. Her sadness today wasn’t out of the ordinary.

Thus, taken at face value, this might have been a typical Monday morning. But it was not. The French had blockaded Vera Cruz’s harbor.

A foghorn blared. No doubt it belonged to the menacers. Alejandra grimaced. Admiral Charles Baudin and his men should have been the widow Sierra’s allies, her father being a patriotic Gaul even though he had lived in nearby Jalapa for many years. But she held no such allegiance to los franceses. Alejandra believed in Mexico. Mexico forever.

“Señorita?”

A ragged Indian girl of about five stepped in front of her and held out a grubby hand. Huge pleading eyes looked up.

Accustomed to such a situation, Alejandra sighed in sympathy and dug into her pocket. “For you, my sweet,” she said in Totonac, placing the silver coin in that palm. “Go with God.”

“Thank you, fair lady.” The girl took off in the harbor’s direction, the coin clutched as if it were a talisman.

No more than a quarter block away, in a less crowded section of the marketplace, the beggar girl stumbled and fell to the patterned marble walkway. A nearby vendor of bananas, exotic birds, and crucifixes fashioned from seashells turned a blind eye.

Alejandra started toward the child.

At that same moment a tall and dashing man rushed to offer aid. Rocking back on his booted heels, he lifted her shoulders from the pavement. Alejandra stopped several paces from the pair, but she couldn’t turn her eyes from the touching sight.

She heard the man’s words of comfort, uttered with deep resonance. Obviously he wasn’t fluent in the Indian’s language. Just as obviously he wasn’t Español. His features were neither fine as a Spaniard’s nor coarse as an Indian’s, and a mixture of the two he wasn’t.

Since he did not look at Alejandra, she couldn’t distinguish the color of his eyes, but he gave the impression of being Nordic: above average height; features etched to rugged and manly perfection; hair the color of freshly scythed flax.

Somewhat out of the ordinary described his clothes. A Panama hat tilted cavalierly above his tanned and mustachioed face, a blousy-sleeved white shirt open at the neck to reveal a hirsute chest, gray linen trousers hugging narrow hips, plus boots of black suede—thigh high above silver spurs. Alejandra detected the outline of a knife in the right boot.

And they were big boots. Even though she had traveled extensively through Europe and the United States, and had seen many towering men in both places, she was struck by the size of his feet and hands. Mexico was a land where men prided themselves on small bones; it was a sign of breeding. But Alejandra found this foreigner’s big bones intriguing.

A breeze ruffled his sleeves, pressing the material against well-developed muscles. To gaze upon the lines of a man shouldn’t have been this interesting to a widow respectful of her husband’s memory. It shouldn’t be, especially since she had never been prone to ogling men.

There was no accounting for Alejandra Sierra’s continued interest.

Except the stranger—he appeared to be around thirty—gave the impression of mystery and danger mixed with compassion. Was that why she was intrigued? Probably. Who wouldn’t be curious about a man certain in his actions, commanding in his presence, and tender in his ministrations?

He smoothed the little girl’s brow and asked in broken Totonac, “Can you walk now?”

She shook her head, perched on his knee, then nestled against his broad chest.

“May I carry you to your mother?”

She closed her eyes before snuggling deeper.

No way was the child giving up that safe haven. And it certainly appeared to be comforting. A bizarre feeling tugged at Alejandra. For the first time since her husband’s death—and possibly a good while before that—she yearned for physical comfort. And ached to be held against a man’s chest. What was she thinking? Such thoughts were not proper!

She flushed, lifted her lace fan, and retreated a step to the side. Cooling her face, she made mental amends. Despite a far different appearance, this man reminded her of Miguel Sierra. Her departed husband, predictable as rain in springtime, had been a compassionate soul, deserving to love and be loved. In her world of Latin tempers—and she had her own—Miguel’s calm, soothing ways had been refreshing.

Poor Miguelito, she thought. Miguel, who loved children and sunsets and fandangos. And Alejandra. He died childless on his twenty-fifth birthday. In March of 1836. He had not died in the arms of his devoted wife. Don Colonel Miguel Sierra y de Leon fell in battle. In the Tejas village of San Antonio de Béjar. At a mission turned fortress called the Alamo.

A tear formed. As clearly as if he were standing beside her, Alejandra could hear Erasmo de Guzman say, “Stop torturing yourself.”

It wasn’t easy, jacking up her chin and sniffing back that tear, but Alejandra did, and felt better for her efforts. Erasmo, friend to both Alejandra and the late Miguel, had been right in his advice. She must quit crying over her husband. All the tears in the world wouldn’t bring him back.

Calm again, she wondered about this kind stranger, who was telling the little girl some story about trapping muskrats as a lad. Who was he? Surely not a pirate, though his clothing outside of the spurs befitted one. Perhaps he was an American? There were many on these shores, Vera Cruz being a cosmopolitan seaport.

Uneasiness tugged at Alejandra. He might be Norman French. After all, Normans were of Nordic extraction. Could it be that he was one of Admiral Baudin’s men come ashore to spy on the Mexicans? Surely not, she reasoned. Even the French wouldn’t be so bold. In bright daylight anyway.

And he didn’t strike Alejandra as an enemy.

“Señorita, you want camarones?” A dirty-faced boy shoved a pungent, cloth-covered basket toward her face. “The boiled shrimp is excellent today.”

“No thank—” Alejandra glanced at the beggar girl. She wasn’t as plump as a youngster ought to be. Taking another step backward, Alejandra whispered to the shrimp monger, “I’ll take a dozen. Give them to the child.”

He flourished his serape, kneeling on the blanket to bundle the huge, pink crustaceans. He grinned at Alejandra as he took her money, then sauntered to hand the parcel over.

The girl looked at her benefactress. “Thank you, generous lady.”

Her rescuer started to glance at the source of that appreciation, but tiny fingers pressing against his cheek stopped him. “Thank you, nice gentleman.” There was a funny look on her face. “Your cheek isn’t smooth like my people’s. It’s all . . . like sand, or something. It tickles my fingers. But it is a nice feeling.”

Barely aware of her actions, Alejandra edged closer to the two of them. The man was laughing at the comment. “Little one,” he said and patted the thin shoulder, “you’ll break many hearts one day.”

She beamed and lowered her chin in sudden shyness. “I will go now.” Paper-wrapped camarones clutched in one hand, her coin in the other, she departed.

Finally the man turned his gaze to the now smiling Alejandra. He levered to stand. Something lit the eyes that were blue as a Nordic fjord. Something akin to recognition. Such an expression from a stranger was unsettling, especially when a grin as sensuous and evocative as the marimba pulled the left side of his face, lifting his mustache, as he said simply, “Doña Alejandra.”

Her smile vanished. How did he know her name and title? Never before had she seen this blond man. Never. Nonplussed and perhaps frightened at this disadvantage, she stepped back. In these perilous times, one couldn’t be too cautious.

“Lovely day, isn’t it?” There wasn’t a trace of an accent to his Spanish beyond a slower cadence and a deeper timbre than was usually detected hereabouts. “Doña Alejandra, may I introduce myself?”

Not a syllable passed her lips. She must not dally here chatting with this mysterious, socially forward person—who just might be French!—when other matters required her attention.

Alejandra whipped around and hurried in the direction of Café Plantain. Over her shoulder she heard the stranger say, “You disappoint me.”

Recalling his kindness to the beggar girl, Alejandra almost turned around. Almost. It took reminding herself that ladies did not engage with those not of their acquaintance, especially in times like these, to keep her feet moving. Besides, she was late for her appointment.

Last evening she received a note from her friend and confidant, Erasmo de Guzman, urging that she meet him at the coffee shop located catercorner to Vera Cruz’s plaza, and that was where she needed to be. Now.

Yet she couldn’t help wondering . . . How did the stranger know her? Could she have forgotten a previous meeting? Surely not. If they had met, she would have recognized him. A man so handsome and considerate would be unforgettable.

You’re making too much of it. Her family, the Toussaints, were well-known residents of Veracruz state; the Sierras, all of whom were now dead, had been even more prominent. It wasn’t unusual for Alejandra to be recognized. But by a foreigner?

You disappoint me. She didn’t wish to mull the source of why the man’s statement bothered her. Nearing Café Plantain now, she decided not to give it one more thought.

A couple of minutes after turning from the flaxen-haired stranger, Alejandra Sierra entered Café Plantain. Here, Veracruzanos enjoyed the finest locally grown coffees amidst the hubbub of coffee brokers conducting business.

Because of her long period of mourning, this was her first visit since word of Miguel’s death had reached her two years ago. She noted the café’s familiar whitewashed and stark walls, the mosaic tiles covering the floors, the din of voices, and the clanging of dishes. The aroma of coffee wafted throughout to cajole customers to cup after cup of the delicious brew.

Several men took time from their refreshments to offer Alejandra greetings and condolences. No one looked askance at her. Frequenting establishments alone was frowned at in some parts of the world, but not here. Especially not at her. Coffee was the mainstay of Campos de Palmas. Of course with the French blockade, business wasn’t good, but she refused to think about that now.

An errant recollection did rush to mind.

You disappoint me.

It was as if the mysterious man were in the main salon of the Plantain, speaking to her with that resonant tone of his. Resonant and filled with . . . with what? True disappointment, she decided. She much preferred the easy tone he had used with the Totonac girl.

The child’s words haunted her, too. Your cheek is not smooth like my people’s . . . It tickles my fingers. . . But it is a nice feeling.

What did it feel like to touch his cheek?

Making her way to a room reserved for private meetings, Alejandra scolded herself for such thoughts. Of course she had loved her husband, but dwelling on intimacies was not only unladylike, it was also uncharacteristic of her.

She entered the room and closed its door behind her. Two men rose from the table. She had expected simply to see the young mestizo coffee broker. With his burly build and coarse features, Erasmo de Guzman couldn’t have been termed handsome, not like that golden-haired pirate, but Erasmo’s expressions and the way he carried himself showed intelligence and confidence.

It was no wonder Alejandra’s sister had once found him attractive. Very attractive.

Not wishing to dwell on that recollection, Alejandra noted Erasmo wasn’t looking her in the eye. Why not? Trying to figure out an answer, she observed the room’s other male occupant. He was old, bent, and small.

This was definitely a day for strangers.

And whatever her friend and his companion wanted, she doubted it had anything to do with friendship or the business of coffee beans. Which had her uneasy for some reason.

“What do you want of me?” she asked quietly, sans the preamble or the social chatter of a typical Veracruzana.

The old man raised an arthritic hand to cup his ear before turning to Erasmo. “What did she say?”

“ ’Rasmo, who is this gentleman?”

“Don Valentin Sandoval of Merida.”

Merida. Capital of the Yucatan peninsula. Center of opposition to the present government. Don Valentin Sandoval. Sandoval—of course! Alejandra was surprised at not recognizing the name immediately, since Erasmo had mentioned it on several occasions. The Yucatecan grandee, a distinguished arch Federalist, was an outspoken critic of the Centralist government.

But what did the consumptive don and Erasmo want from her? Don’t be loca, she scolded herself. This meeting must have something to do with the subject near and dear to Erasmo’s heart. A cause he had instilled in Alejandra. Promoting a Federalist government.

For years Mexico had been divided into two camps, Centralist and Federalist. The former was in power, granting favors to those in the upper classes. Her faction, on the other hand, believed in liberty, equality, and fraternity for all. As well, they embraced the doctrine of states rights over a Centralist regime where all authority was vested in a few corrupt men in the capital. They took no regard of practicality and didn’t understand—or care!—that what worked for Veracruz state wouldn’t necessarily be right for Chihuahua or the Pacific Northwest or the Yucatan. And vice versa.

At present, nothing was right in the government. And with the French obstructing free trade—

“Alejandra? May I seat you, please?” At her nod, Erasmo helped her into a chair at the small round table. “We have much to discuss, amiga,” he murmured.

“We have much to discuss,” Don Valentin Sandoval interjected with no signs that he had heard Erasmo.

The closed door rattled as a waiter knocked before entering. High above his shoulder, he carried a linen-covered tray. “Buenos dias,” he said and set his burden on a table by the wall. He poured coffee from a battered pot into tall, stemmed glasses, then did the same with a pot of hot milk.

Whistling a tune that had overtones resembling “La Marseillaise”, the fresh-faced young man—he couldn’t have been older than sixteen or seventeen—flourished a linen-covered plate from his tray.

He pulled up the covering. “May I interest you in chocolate eclairs?”

Alejandra blanched, as did her table mates. Despite the warm day, the air took a sudden chill.

“French pastries!” squawked the octogenarian. “Take them away!”

“But they are very tasty.”

“Felix, have you lost your mind?” Erasmo glared at the waiter. “We don’t eat French food. Not with the Gauls cutting our supply lines and customs revenues.”

“Ah, Señor de Guzman, where is your sense of humor?” He replaced the offensive pastries on his tray. “Back in the kitchen we find much mirth in it. Ochoa the chef has even come up with words to a song. It goes like—”

“Felix! There is a lady present.” Erasmo pointed at the young man. “Watch what you say.”

Giving a nonchalant shrug, Felix said, “The words are not offensive to any Mexicana or Mexicano, I assure you. It goes like this, The day the Gloire arrives here, is the day the Gloire will be sunk.‘” He terminated the verse. “Granted, she is here smelling up our harbor, but that’s not the point. This siege started over no more than a chocolate eclair, so why not mock the French with their foolish ‘pastry’ claims?”

“Foolish pastry claims?” Alejandra repeated, unable to keep mum. “No one should count them as trivial. The French don’t, be assured.”

“You’re not much more than a niño, Felix.” Eyeing him, Erasmo took a sip of his coffee. “Are you fully aware of what precipitated the French aggression?”

“What did you say?” the don asked, leaning closer. Erasmo did not repeat his question, which sent the Yucatecan into a sulk.

Felix answered Erasmo’s query. “I don’t know a lot about the politics of what happened, but I do know it had something to do with some Frenchman’s bakery in the capital getting sacked.”

Alejandra had been in England at the time of the incident, but she was well aware of the happenings. It all started ten years ago, and seven years into the chaos following Spain granting Mexican independence.

A squad of Mexican soldiers had descended on the pastelería. Caught up in what turned out to be a crude fiesta, they gobbled down their eclairs. The situation turned ugly when the proprietor presented the bill. The soldiers not only refused to pay, they destroyed the bake shop.

“It started with that,” she said as Don Valentin coughed into a linen handkerchief, “but the whole thing got more serious right away.”

Erasmo nodded. “His demands were a rallying cry to other ex-patriots living in our country. Thousands of them came forth, demanding money for insults.”

Felix had a pensive look to his face. “Well, I don’t know about the others, but I think that baker deserved a settlement. That’s what the Federalists are working for, you understand. Fair treatment for everyone.”

Erasmo and Alejandra exchanged covert yet knowing looks. Since he had introduced her to Don Valentin—this was the first time she had been in company with Federalists other than Erasmo—would he also mention to the waiter that she was likewise aligned? He didn’t.

He responded to Felix’s comment. “The other claims got out of hand. One after another after another, until there were thousands of claimants, they came forth and demanded money from the government. They complained of forced loans and lack of police protection. And of things such as looted property and false imprisonment.”

Leaning a hip against the side table, Felix crossed his arms. “If they were victimized like that other hombre, who could blame them?”

Alejandra smoothed the skirt of her black dress, and spoke up. “Most of their claims are of the nuisance variety . . . if not absolute falsehoods. As for those who have legitimate claims, they have suffered no more than any Mexican has. We’ve all been touched by revolution and strife. And a bankrupt treasury.” The last part was the result of war and Centralist corruption, but she wouldn’t make mention of that.

Don Valentin waved a crabbed finger. “That’s right, young man. We have no money to pay those Froggies. Even if we wanted to. Which we don’t, of course.”

Felix nodded. “Let them eat—What was it their la reina Maria said? Oh. Let them eat cake.”

No one corrected the misquote.

Alejandra didn’t hold such a blasé opinion as Felix. King Louis Philippe of France meant to collect the supposed debt now embracing the million peso mark.

And he would go to any lengths to do it.

Thus, French frigates had been menacing the waters of Veracruz for several months, and lately Charles Baudin, the one-armed and fearsome rear admiral of Louis Philippe’s navy, had arrived with more warships as well as with the king’s third son.

Five years ago, upon her presentation to the French court, Alejandra had met the foppish young prince and knew him to be aggressive. What did he think to accomplish by being a part of the fighting fleet? She shuddered. If the Gauls were to prevail in battle, wouldn’t it be convenient, their having an ambitious young prince ready to claim Chapultepec Palace?

She was only vaguely aware of Felix refilling the coffee glasses and of his exit from the room, so caught up was she in the thought of Mexico becoming an empire again. While she was strongly against the Centralist government, Alejandra was more adamantly opposed to any possible invasion by foreign forces intent on stealing Mexico for empire purposes.

She stirred her coffee, then took a meditative sip. Before Miguel died, she couldn’t have cared less about politics. As a girl she had been as untamed as the jungles of Veracruz, as wild as the chipichipi rains that tormented her hometown of Jalapa. Much to her parents’ dismay, Alejandra had ridden bareback and hell-bent, laughing at life and loving every minute of it. Time after time, Papa had thrown his arms wide to lament in his peculiar mixture of French and Spanish. “Sacrebleu, Mamacita, what will we do about un garçon manqué?”

Mamacita had had a solution, and not just for the family tomboy. She shipped Alejandra and her equally bratty sister off to Europe for “smoothing out.” With Mercedes the lesson had backfired, for the elder Toussaint sister had become more wild and untamed. Alejandra had returned with reserve, ready to be united in an arranged marriage to the wealthy young heir to the Sierra name and fortune. As a bride Alejandra had wanted nothing more than her husband’s devotion and a houseful of children. As a widow she wanted justice for her country.

She placed her glass on the table. Glancing from Don Valentin to Erasmo, she said, “I suppose this meeting has a purpose. What would it be?”

The two men eyed each other. In a gesture unlike his usual confidence, Erasmo swallowed nervously; his Adam’s apple bobbed as he studied the wooden table. Don Valentin rubbed his wrinkled mouth. Their hesitation distressed Alejandra. She had the urge not to press the subject, to say adios and be gone.

If you’re going to live in a man’s world, she told herself, be as bold as a man. “Speak up. One of you.”

The older of the two cleared his throat, then blurted, “You must help us rid Mexico of General Santa Anna.”

The mere mention of that despot’s name twisted her stomach into knots. Santa Anna. General Antonio López de Santa Anna Perez de Lebron. Former president and dictator of Mexico. Some styled him the Napoleon of the West, a name generated by Santa Anna himself. No longer was he called that. Like his Corsican counterpart, Santa Anna had met his Waterloo.

For him that place had been San Jacinto, an obscure region in the southeastern Texas, or Tejas as the Mexicans knew it. There, in April 1836 and six weeks after the Alamo and Goliad fiascos to the west, General Sam Houston’s small, ragtag army surprised and finally defeated the Mexican forces.

Before his downfall, nonetheless, Santa Anna had dug his Centralist claws into the flesh of many—including that of Alejandra’s young husband. Miguel Sierra, infantry colonel on attack against the Alamo, may have been struck by rebel guns, but in her heart Alejandra believed he died from the tactical errors and bloodthirsty excesses of his own commander.

A man without honor or principles.

Santa Anna was that. After his shameful victory at the Alamo and the annihilations of the Goliad rebels, after his ignominious defeat at San Jacinto, in the aftermath of giving Tejas away to the Anglo filibusters, he undertook a strange odyssey, traveling far and wide in search of a country that would sanctify his actions in Tejas. His search was unsuccessful. Several months ago Santa Anna had returned under cover of night to the country he disgraced in more ways than Alejandra could count on her fingers and toes.

“Amiga?”

Erasmo’s gently spoken word pulled her back to the present. “Why rid Mexico of Santa Anna?” she asked, fastening her hazel gaze to the brown of his. “President Bustamante, in his only action I’ve approved of, has decreed he stay exiled at Manga de Clavo.”

“Which is right outside our city,” the don reminded.

“Yes, Santa Anna’s estate is near Vera Cruz, but with the French in our puerto, he should be the least of our problems.”

Don Valentin coughed again, and Alejandra handed him a glass of water. “Would you like to take a rest?”

He shook his head. “No. This meeting is too important.”

“True.” Erasmo got back to the business at hand. “Alas, our fallen president will use the blockade to his best advantage. Already he’s sent word: his services are available. He yearns to defend San Juan de Ulúa. By driving Admiral Baudin from these waters, he figures to ride a wave of popularity all the way to Mexico City.”

She almost laughed “That will never happen. Mexico won’t give that cretin another try.”

“Complacency is folly,” Erasmo said. “Our defeated leader is a man of high charisma, and his offer could be taken as one of a savior by many of our people. Some are still loyal to him.”

She quivered with revulsion, thinking of Mexican vulnerability to enemies from abroad and from within.

“Amiga, the French have presented him with the opportunity he’s been waiting for.”

Was it only a moment ago she had thought the most dangerous threat to Mexico was France?

Odd, how matters could change in the blink of an eye. Suddenly it all was too much for her. She would have welcomed her bed, its covers pulled over her eyes.

Coward!

She leaned toward the wheezing Don Valentin. “The people might be duped into returning Santa Anna to power.”

“Exactly,” he replied.

“Unless we stop him, amiga.”

Don Valentin nodded. Composed now, he said, “Doña Alejandra, you are the key. You’re the most beautiful woman in Veracruz . . . and you’ve come to a certain party’s attention. We want you to play on his weakness.”

Alejandra overlooked the expansive praise. “I’m insulted you would ask.” She glared at both of them, then shored up her dignity to present facts to free herself from commitment. “Besides, I’m much too old for the general. Twenty-two. And I’m a widow, certainly no virgin. Santa Anna prefers females of the nubile variety.”

Erasmo colored. The Yucatecan, having no problem comprehending, choked on his coffee.

“We don’t mean you should offer yourself to Santa Anna,” Erasmo amended, indignation in his tone.

Too often she rushed to conclusions, and a blush heated her face at this one. “What . . . what do you mean, ’Rasmo?”

“Until the French can be paid, or repulsed from these shores, Santa Anna must be stalled from entering San Juan de Ulúa.” Erasmo rubbed his lips. “There’s an American adventurer, a man called Reece Montgomery. We think he’ll help us stall Santa Anna.”

She rolled her eyes and clicked her tongue. “For curiosity’s sake, and for no other reason, I’d like to know how you figure I would fit into this intrigue.”

“We need him as a spy and we’ll pay him to be one. You’ll convince him.”

“No, gracias.” .

Erasmo patted his hand in the air, chest level. “Would you allow me to finish before saying no?” He rushed on. “Under mysterious circumstances Montgomery aligned himself with Santa Anna. The circumstances were strange, but his motives are not. Montgomery can be bought. He went like this”—he snapped his fingers—“to Santa Anna’s payroll. Among the army being collected, we know there is no man as corruptible as Señor Reece Montgomery. So . . . we intend to raise his salary.”

She laughed. “The nuns from the Insane Hospital should pull you to their bosoms. Surely this Montgomery you speak of won’t fall for some harebrained scheme.”

“We think differently,” Erasmo replied. “He holds an allegiance to money, nothing else. Yet he, like Santa Anna, has a weakness for ladies. To his credit, though, Montgomery favors women to girls.”

“Oh, ’Rasmo, how very kind of you to think of your best friend’s widow,” Alejandra retorted in scathing outrage. “You, a tower of strength in my widow’s grief.”

He took her hand. “I mean no disrespect. All we’re asking is for you to gain Montgomery’s trust. That is all.”

“Why doesn’t some man approach him? Why would you choose me for the deed?”

“What was that?” the grandee asked. She repeated her question and he nodded, “Understand, Doña Alejandra, Montgomery has seen you.”

For some strange reason, Alejandra thought of the foreigner in the marketplace. Could they be one and the same? Preposterous!

Don Valentin went on. “He’s made inquiries about you. Is she married?’ ‘Is she pledged to another?’ Those sorts of questions. If you’re with him, no suspicions will be aroused. After all, your late husband was a martyr to the Santanista cause. Sierra loyalty won’t be que

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...