TWO DAYS BEFORE Hannah’s father disappeared, he took her out in his boat.

It was an aluminum boat, flat and small with a pull-operated motor. Before they left, her father checked the gas and oil levels.

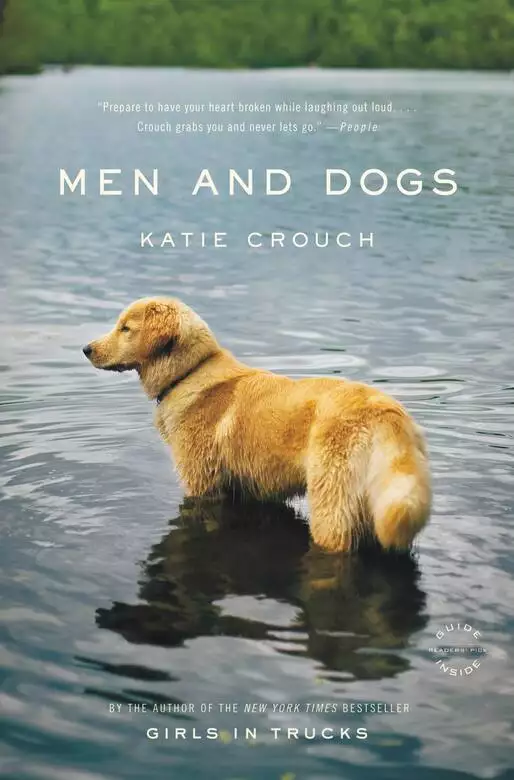

Hannah held Tucker, the dog, on a leash.

Hannah was still small then. Eleven years old. Her hair was streaked with green from afternoons spent in the neighbor’s pool.

She wasn’t pretty. She had her father’s powerful features, and they were too large for her face. She wore a long T-shirt and

red sneakers. Her bathing suit snaked up in bright lines around her neck. She wasn’t unhappy. She’s always been good at waiting.

There was no plan for the day. There never was.

The Legares were a family who navigated by the outlines of Buzz’s whims. The children had become excellent at collecting information.

It was a survival tactic. They eavesdropped, they spied. Hannah’s brother taught her how to open and reseal mail over a pot

of steaming water.

That morning there had been a fight. Hannah listened to the dull murmurings of it through the bedroom wall, the voices spiking

in volume, then falling flat to silence. Shortly after, Buzz stepped out into the hall.

I’ll take Hannah, he said.

His voice through the door.

Her mother’s laugh.

Take her to China if you want to, she heard her mother say. I don’t care.

Hannah sat up. It was time to go.

Hannah, now thirty-five, remembers some details perfectly clearly, as if they happened just a moment ago. They bounce in her

head, meaningless shards of color and sound. When she is ordering coffee. When she is in line to get on a plane.

Other things she knows she should recall—large events and happenings—now somehow eradicated. Sometimes she squeezes her eyes

shut and scrapes her mind, trying to get to them.

She still has this list. Items she and her father took on the boat trip, written in an eleven-year-old’s cursive on Hello

Kitty paper, carefully folded and stored.

1 jug of water

3 bottles of Coke

4 cans of Budweiser

2 bologna sandwiches

1 net

1 package chicken necks

1 portable radio

1 fishing pole

2 hats

1 bottle of sunscreen, SPF 15

1 dog

When they were ready, Hannah untied the bowline and waited on the dock while her father pulled the cord. The engine sneezed,

rumbled slightly, and died.

Damn it, Buzz said.

He looked up at his daughter and smiled.

Don’t tell your mother.

She nodded. There were going to be many things she wouldn’t tell her mother.

The boat started. Buzz steered them away from the Boat Club and turned the engine knob all the way to the right. Hannah stared

at the shrinking land.

Always nice to leave, isn’t it? her father said. Where should we go? China?

I don’t know.

China.

No!

We’ll send them a postcard.

No!

You’re right, no postcard.

Hannah…

Yeah?

How many bones are in the body?

Two hundred six.

Hannah’s father was a doctor, and she planned on being one, too.

How many cells?

One hundred trillion.

One hundred trillion, her father repeated, looking out at the water. He took a swallow of beer.

He was tall and, at forty-one, still lean from runs around the Battery. People remembered him as the high school track star.

Buzz Legare wasn’t staggeringly handsome, but he was disarming. People wanted to be near him. Men pointedly used his first

and last name in conversation. Hannah noticed that waitresses lingered after taking an order, even when her mother was there.

Aren’t you going to crab? he asked. We brought all of these chicken necks.

Hannah sighed. She didn’t want to crab. She wanted to read about Kirk Cameron.

Pretty soon a day on the boat with your dad will be the last thing you want to do, he said. Pretty soon, it’ll all be about

makeup and boys.

OK. I’ll crab.

Buzz turned on the radio. He always sang. He’d start out with a hum, and then would become overwhelmed with the desire to

perform. He never knew the words. He didn’t care.

Go-go, Hannah said.

What?

Go-go.

Are you sure?

I learned the words so I can lip-synch them.

Lip what?

Lip-synch.

Buzz cocked his head.

We pretend to sing them. My friends and I. Like on a show.

Who pretends? he said, casting his line.

Everyone. It’s a show.

Do me a favor, kid. Don’t pretend. Just sing.

She looked at him, mouthing, Wake me up before you—

Out loud, he said.

It was midday, and men, both black and white, were sitting out in the sun, legs spread, fishing poles in their hands. They

stayed on separate docks, but their children spilled into the river together, floating side by side on Styrofoam boards. Some

of them waved. Hannah waved back.

Suddenly, a scream cut through the sound of the motor. Hannah jerked her head toward the shore. On one of the docks, people

were running and gathering around something lying flat.

Kevin! someone shouted.

A woman was crouching, shaking a boy’s shoulder.

Kevin! Will someone—Kevin?

Hannah’s father knocked about the boat like a large caught fish, swearing as spray lurched up behind with sick, slapping sounds.

They slammed into the dock.

A boy had been stung by a bee. He was in shock. His throat was swollen, and his tongue was the size of a pickle.

I’m a doctor, Buzz told the boy’s mother. He always stood up a little taller when he said this. Hannah, get my doctor’s bag.

Center console, in the flare box.

Hannah ran back to the boat, found the flare box, and retrieved the bag, a perfect leather triangle that opened and closed

with a reassuring snap. Inside, set rows of neatly arranged syringes, bottles, and rubber tubes. One of her favorite things

to do was to put her hand inside. It was always cool, as if it required its own separate air.

Later, Hannah looked up what would have happened if her father hadn’t stopped to help that day. The bee venom was almost as

lethal as cyanide for the boy. When the tip of the stinger pierced his skin, an army of histamines split from the heparins

and flooded his body. Water was released from the cells, causing his skin to strain against the liquid. He would have turned

blue and choked on his own tongue while his mother watched.

Afterward, a party. The boy’s father brought out another cooler of beer, and the neighbors came, carrying plastic folding

chairs and bags of potato chips and a great bowl of pink, curling shrimp. Candy-lipped mothers rushed back and forth with

more food. The afternoon poured away.

We have to go, Buzz said after a while. Thank you for the good time.

So we’ll come see you, Doc, the boy’s mother said. She was leaning into him slightly. You’re our doctor now.

Buzz looked down at her and squeezed her shoulder. There was a pause, then he broke away and began running. Hannah and the

others watched, openmouthed, as he did a cannonball off the dock.

He’s swimming! the boy screamed. The doctor is swimming!

He ran after Hannah’s father and flung himself in the water. Now people all over the dock were following Buzz. They jumped

in with huge splashes, showing off awkward half dives in their shirts and shorts.

Come on, Hannah! her father yelled. He spouted water through his lips.

No, that’s OK, she said. She was worried about her hair. She’d sprayed it up, a proud open lily.

Hannah! Swim!

She shook her head. The boy’s mother was swimming near her father. She gave him a little splash.

Hannah, he called. How many times a day does a human breathe?

Twenty thousand.

How many heartbeats?

A hundred thousand.

Come on, sweetie.

No.

Scared?

No.

Come on, honey.

Why?

Because.

Why?

There won’t always be a why.

They were all waiting. Her father, the not-dead boy, his mother, the strangers. It was April 6, a day she would come to circle

in red each year and label: dad. 1985. What was happening? Hannah Legare can tell you. It was the year of New Coke. The number

one song was “One More Night.” Christa McAuliffe was slated to ride the Challenger. Ronald Reagan was sworn in for a second term. As for the Legares—they were still a family. Hannah, eleven; Palmer, thirteen;

Daisy, thirty-six; Buzz, forty-one.

On April 6, Hannah was a plain sixth grader with a bad perm. She was a bit scared of the water, and was shivering on a dock.

She closed her eyes and listened to her heart, then held her breath to try to make it stop. It didn’t, so she jumped, because

her father told her to.

WHEN HANNAH OPENS her eyes, she knows something is wrong. She sits up slowly, orienting herself. There is a ripping sound as her skin parts

from the hammered-leather couch. It’s not the sort of couch she would ever buy; nor would she purchase anything resembling

the fluffy, synthetic white rug spread across the concrete floor, nor the enormous plasma TV and entertainment system complete

with Wii, nor the oversize, framed sci-fi movie posters. But, having been turned from her home, Hannah is currently subletting

an overpriced, furnished loft in San Francisco’s South of Market district. The place is cavernous. The ceiling is twenty feet

high; the gray walls yawn past the gleaming kitchen to a cold bedroom housing a large closet filled with old computers and

an S&M-worthy wrought-iron bed. Though many, she knows, would be impressed by the loft’s Trekkie-esque grandeur, Hannah can’t

help but see it as a very expensive, geeky prison—pretty much where she deserves to be living right now.

She sits up and takes a reluctant lap around the space. Her husband must have carried her up, dumped her on the couch, and

left. She sits on the kitchen stool and rubs her eyes. Clothes are strewn on the floor, dishes and take-out containers litter

the stone countertop. She is still drunk, but it is not a pleasant state of intoxication. In an attempt to solve this, she

pours herself a drink. Then she reaches over and picks up a pad of paper and a pen in order to make a list.

Better rug

Better sofa? (How long will I be here?)

Music contraption

Pictures of normal people

More wine

Husband

She sighs and throws the pad down again. So Jon didn’t stay. She feels the dull reality of it, a cold ache. She pictures where

her husband might be now. At a club, maybe, leaning into Denise on a velvet banquette. Or, worse, with Denise in Hannah and

Jon’s bed—a mattress selected according to her own finely tuned appraisals of width, springs, and plushness. No, her husband

wouldn’t do that. Would he? She doesn’t know, actually. She’s not sure anymore.

Maybe he called? She finds her purse. No missed calls. No messages. She tosses the phone on the sofa, wondering how this happened

to her. Yet it didn’t happen to her. She did this. Still—Denise? She’s a PR consultant, for God’s sake. A very pretty one, and smart, but… she’s a twentysomething

hippie. She teaches a hula-hooping class in her spare time. Whereas Jon is a man—a nerd, really—who believes that Craig Newmark

deserves the Nobel Peace Prize. Who never swears. Who subscribes to Tin House and The Believer and actually reads them cover to cover. His light-brown hair in the morning looks like hay; his favorite possession is his mother’s quilt; he

once threw a party to plan Britney Spears’s mercy killing. He’s dorky and hilarious and generous and perfect and she’s really

fucked up this time and has to do something about it.

Hannah finishes her vodka soda, tops it off with half of a sugar-free Red Bull left in the fridge by the previous renter,

then downs a tumbler of water to stave off tomorrow’s hangover. (A futile attempt, but each new day deserves a fresh chance.)

She molts the dress, puts on Jon’s favorite outfit—jeans, T-shirt, braless—and calls a cab.

Even after more than fifteen years, Hannah still has a mad crush on San Francisco. She loves the confectionary mansions, the

thickets of crack dens, and the dense, surprising pockets of eucalyptus. The cultural compartmentalization warms her—Hannah

can look at nearly any person she meets and almost instantly peg where they live. That girl in the Atari shirt and the green

eye shadow? The Mission. The guy in the pink button-down and Dockers? Somewhere in between Cow Hollow and Pac Heights. The

Indian guy in the jeans with a knife crease is Potrero. The woman with the sport top and the sunburned nose, either the Presidio

or the Outer Richmond—somewhere with enough room for her surfboards.

The car slams on its brakes. A homeless man darts in front.

“Careful!” she shouts.

“The guy’s on meth,” the driver says. “What do you want?”

They stop at a light. Hannah turns back to look again, checking the man’s height, hair, approximate age. Too short—not her

father. She leans back into the seat, the man leaving as quickly as he came, replaced by what she will say to her husband.

The words slip dangerously through her mind.

I didn’t mean to. No. I meant to, but I’m really sorry about it. Try again. I was stuck. I was depressed. Too much “I.” You are everything to me. God. Without you I am a meaningless pile of nothing. Maybe. Please. Maybe that?

The light turns green. The man retreats to the shadows, out of the limits of her sight.

Hannah sees her father about once a month. Not all at one time, of course. Not the whole person. And never when she’s consciously

looking. Last week, she saw his shoulders at a wine store. Then one of the buyers at Saks surprised her by having his hair:

early-forties thickness, light brown with a little gray.

Her biology professor at Stanford had his nose. It was the first time she’d seen the nose on anyone other than her father—a

rare find. Since then, she’s spotted it only on the face of her hair stylist and one of the contestants on Top Chef. During the first class she had with the nose, she was mesmerized. It was a stupid class, and, as with many at Stanford,

Hannah coasted through on autopilot. Still, after seeing the nose, Hannah found herself going to office hours twice a week

and spending long, unnecessary tutoring sessions with its owner.

The rest of the man was nothing like Buzz. Short and dark, with bushy eyebrows and a smug, charmless voice, he immediately

assumed Hannah had a crush on him. And who could blame him? She constantly made up excuses to see him, thought up inane questions

about plant phyla and bird species and brought in flowers plucked from the quad. At first the Nose seemed to find her charming,

but near the end of the term, he became exasperated.

“I have a wife, Hannah,” he said, his caterpillar eyebrows straining to meet. “This is very flattering, really. Listen, you’ve

got an A. An A plus, if there is such a thing. I promise. Just please, don’t come back.”

Hannah didn’t bother to tell the professor her story, because doing so would be a self-indulgent action that would defeat

the proverbial point of moving to California. For that reason very few people know that she has a father who went fishing

at dusk when she was eleven and never returned. They don’t know that Buzz Legare disappeared into thin air, leaving no note,

body, or explanation.

The fact is, Hannah has a hard time getting those close to her to understand how she could be so preoccupied by someone who

left more than twenty years ago. Under her mother’s direction, she and her brother were discouraged from hanging on to things.

Sentimental clutter in the form of, say, photo albums and bulletin boards are not encouraged in the Legare family. Daisy is

nothing if not a responsible mother; after her husband’s disappearance, Hannah and Palmer were dutifully sent to church and

to see a family counselor, his office complete with painted inspirational posters bearing troubling slogans such as PUNISHMENT HALVED IS JOY DOUBLED! and YOUR YESTERDAYS ARE ONLY YOUR TOMORROWS, AGAIN.

Did the sadness subside? It did. And that’s exactly when, with a groaning crack, the glacial divide in the Legare household

began to form. For her brother, Palmer, the topic of her father was closed. Her mother, too, seemed over it, having remarried

within a year, something Hannah has never quite been able to forgive her for.

So Hannah entered her twelfth year more than a little baffled. She still had—has—questions. For her, an empty boat floating on the harbor is not an obvious conclusion.

Hannah believes her father is alive. As in, still in existence and breathing the same air as she is, on this very Earth. It’s

not that she isn’t tempted to believe otherwise; there are just too many unexplained factors. For instance, how does one fall

off a boat on a calm spring evening? And why did no one see her father out in the harbor? And why was he fishing on a Monday

at twilight? And if he drowned, why was no body ever found? And finally, why, why was the dog still there?

After six years of probing, Hannah succeeded only in estranging herself from her family. Palmer, Daisy, and her stepfather

were tired of her questions, tired of what they saw as her relentless desire to cause upheaval in their lives. “What do you

need?” Daisy once snapped in exasperation. “A shark-eaten carcass?” So when it came time for college, it became clear that

Hannah’s best option was just to leave. Since high school graduation, she’s been back to Charleston only four times: a wedding,

a Christmas, a funeral, and once with Jon—each visit an awkward jail sentence. It isn’t that she doesn’t appreciate the place.

Who wouldn’t adore the beaches and a local accent so complex it allows a woman to simultaneously seduce and reprimand in one

single word? She probably loved it more than anyone, right up until that day in April when her father took off in his boat

to find something better. A crappy thing for him to do, but as she’s gotten older, she’s come to admire her father for it.

She’s almost grateful, even. Because certainly her father’s departure gave her an unquestionable license to leave without

looking back.

And she’s thriving, isn’t she? Stanford, a start-up, then Stanford again for business school, and now another start-up out

of the ashes of the first. Three marathons, two biking centuries, a marriage (albeit slightly screwed) to a highly appropriate

life partner.

Her father never would have dreamed of such a future for her. Often she wakes up in the middle of the night, wanting to tell

him. I’m killing it, Dad, she’d say. How about you? She googles his name once a week. He left long before the Internet; still

she sends e-mails to the kinds of addresses he might choose—

[email protected],

[email protected]. But she receives only auto replies from strangers. Action failed. Error. Your message did not go through.

Taxis always have trouble finding Hannah and Jon’s Upper Terrace apartment, and this one’s no dif. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved