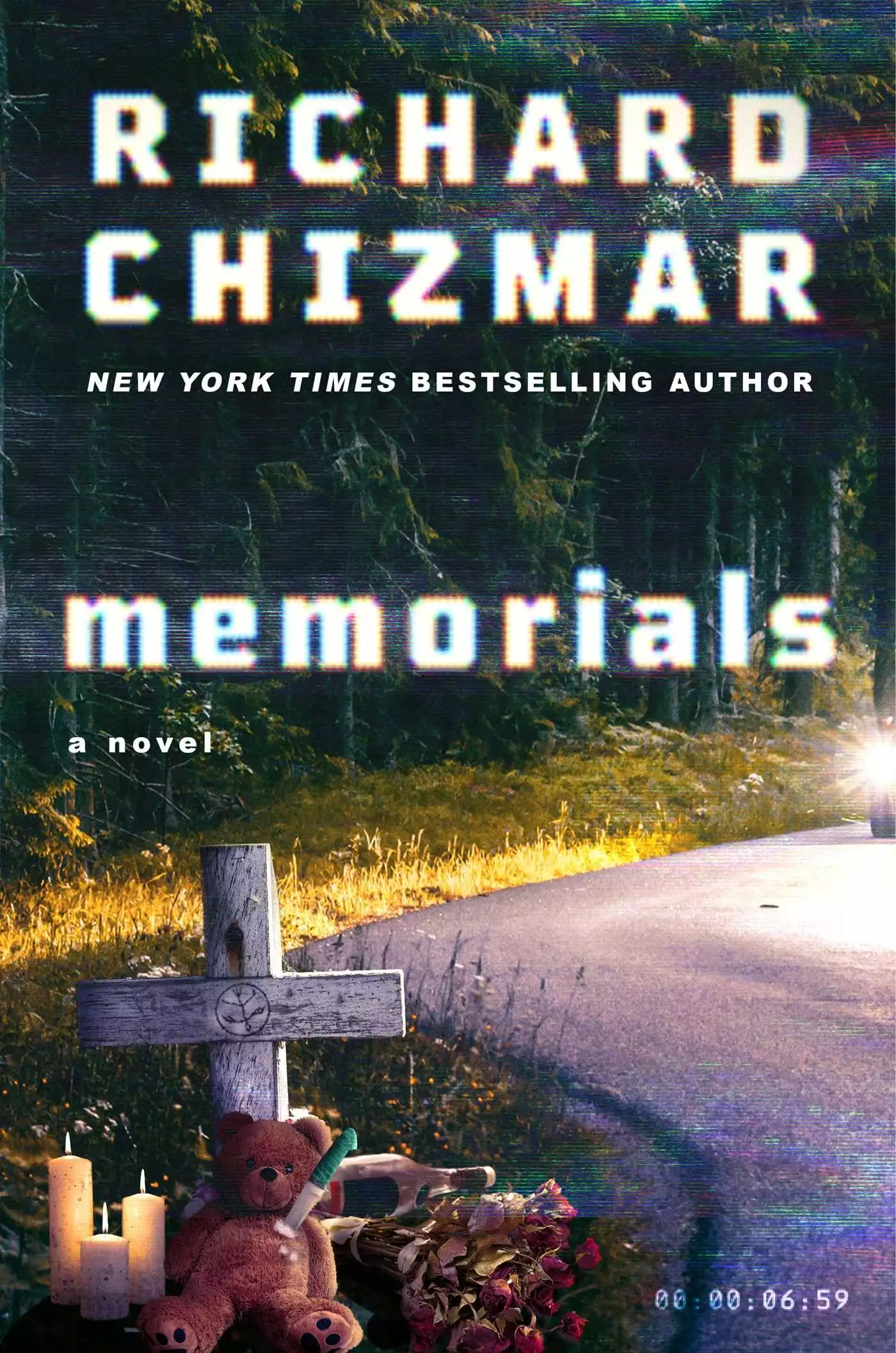

Memorials

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A group of students encounter a supernatural terror while on a road trip through Appalachia in this chilling new novel from the New York Times bestselling author of the “unforgettable and scary” (Harlan Coben) Chasing the Boogeyman.

1983: Three students from a small college embark on a week-long road trip to film a documentary on roadside memorials for their American Studies class. The project starts out as a fun adventure with long stretches of empty road and nightly campfires where they begin to open up with one another.

But as they venture deeper into the Appalachian backwoods, the atmosphere begins to darken. They notice more and more of the memorials feature a strange, unsettling symbol hinting at a sinister secret. Paranoia sets in when it appears they are being followed. Their vehicle is tampered with overnight and some of the locals appear to be anything but welcoming. Before long, the students can’t help but wonder if these roadside deaths were really random accidents…or is something terrifying at work here?

Release date: October 22, 2024

Publisher: Gallery Books

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Memorials

Richard Chizmar

PROJECT PROPOSAL

Date: April 18, 1983

Class: American Studies 301

Instructor: Professor Tyree

Group Members: William Anderson, Troy Carpenter, Melody Wise

Roadside Memorials: A Study of Grief and Remembrance

We’ve all seen them. On our way to the grocery store or the post office or a faraway vacation destination. Keeping a lonely vigil on the side of the road. Stark white crosses, surrounded by candles and photographs; stuffed animals and flowers; ceramic angels and red or yellow ribbons. We slow down to take a look, shake our heads in regret, and then continue on our way—and they’re forgotten.

Roadside memorials not only honor the accidental death of a loved one, but they also play an important role in the grieving process for surviving family members and friends. They often form a connective thread of remembrance and help survivors to maintain an emotional bond with the departed.

Roadside memorials originated in the early 1800s, most prominently in the American Southwest, especially in what is now Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. Many Latin Americans placed such memorials to mark the location where their loved ones died. The first documented memorial to appear on the East Coast was in Connecticut in 1812.

Now, in 1983, there are thousands of such memorials scattered around the nation’s bustling highways, suburban streets, and remote backroads. So many, in fact, that there is talk of legislation and regulation in some states/towns/counties. Even outright bans. But for now, these emotionally charged shrines remain a relatively new and increasingly controversial development.

And behind each of them is a story.

Our group proposes to travel by automobile throughout central and northwestern Pennsylvania on a five-day road trip. Utilizing a variety of visual mediums (still photography, film, and video), we plan to create a sixty-to-seventy-five-minute documentary entitled “Roadside Memorials: A Study of Grief and Remembrance.” This visual presentation will be supplemented by dramatic commentary, as well as personal interviews with family members and close friends of the accident victims.

We will begin our journey on the campus of York College and then travel north via I-83 and a network of backroads, following the shoreline of the Susquehanna River. On our first night, we will stop in Sudbury, Pennsylvania, the hometown of group member Billy Anderson, where a very personal roadside memorial dedicated to his late mother and father still stands.

From there, we will navigate a winding path to the northwest, venturing deep into the heart of Pennsylvania’s Appalachian region. We will drive without a preplanned route, wandering with a purpose, searching for roadside memorials and attempting to discover the heart-wrenching stories behind them.

VIDEO FOOTAGE

(8:43 a.m., Friday, May 6, 1983)

The sound of muffled voices over a dark screen.

After a moment, the lens cap is removed and we are greeted by blue sky and bright sunshine. The camera angle shifts and we see an orange Volkswagen van with black side panels parked at the curb. The rear double doors are standing open. Off to the side, on the nearby sidewalk, is a jumbled heap of what appears to be camping gear: knapsacks, a fishing pole, a rolled-up tent, a pair of lanterns, and folded-up lawn chairs. There are also two large Coleman coolers and a half-dozen brown paper grocery bags filled with packaged food.

A young woman——olive skin, dark eyes, long brown hair tied back in a ponytail, wearing a yellow sundress and white high-top Chuck Taylor All Star sneakers——emerges from the back of the van. She appears out of breath. A sheen of perspiration glistens on her bare arms. The camera zooms close. She sees it——and sticks out her tongue.

“Camera equipment’s all loaded,” she says. “What do you think? Food next, then the gear?”

“I think Billy should put down the camera and help pack the van,” an off-screen voice says. “We’re already behind schedule.”

A young man carrying two grocery bags appears in frame. Brown-skinned and diminutive, he’s dressed in tan khaki shorts and a matching button-down shirt. A red bandanna is tied loosely around his neck. He’s wearing thick-framed glasses and his hair is styled in a large Afro.

From behind the camera, a cheerful male voice announces: “Meet Troy Carpenter, ladies and gents! Say something, Carp!”

Troy places the bags in the back of the van and glances over his shoulder. Adjusting his eyeglasses, he frowns and says, “Something.”

The man holding the camera groans and slowly pans to the roadside where their female companion is leaning over to pick up a grocery bag. “Your turn, Mel. Introduce yourself to our adoring audience.”

She spins around, her face lighting up into a million-dollar smile. Her teeth are very white and perfectly straight. We see a scattering of freckles across her nose and cheeks as she gives the camera a flirty wave.

“Hello, adoring audience! My name’s Melody Wise. I’m here in York, Pennsylvania, on this beautiful Friday morning with the grumpy ‘Boy Wonder’ Troy Carpenter…” She gestures at the camera. “… as well as ‘Billy the Kid’ Anderson, our esteemed camera operator. As soon as we finish loading up the van, we’re hitting the road in search of life’s——and death’s——eternal truths.” Her smile fades and she shrugs. “That’s all I got. I’m still half-asleep.”

“You did great,” Billy replies, and we see his blurry thumbs-up surface in front of the lens.

And then the screen goes dark and silent.

DAY ONEFRIDAY | MAY 6

Later, when the trip went bad, I would remember the bleeding man on the bicycle and wonder if he was a sign of things to come.

The van—a Volkswagen Westfalia pop-top camper that, from the moment I first laid eyes on it, reminded me of the Mystery Machine from Scooby Doo—belonged to Melody’s sister.

Tamara Wise was six years older than Melody and more of a mother figure than a sibling. She’d bought the van used from an old stoner who manned the ticket booth at a drive-in movie theater in Richmond, Virginia, where Tamara worked as a secretary in a real estate office. It was the first vehicle she’d ever owned and she was very proud of it. Once she managed to accumulate enough vacation days, she and her boyfriend planned to hit the road and explore the coastline of New England, something she’d dreamed about doing ever since she was little.

After a lengthy and at times rocky negotiation, Tamara agreed to rent the van to us for the princely sum of $300. I’d bitched and moaned about unfair price gouging, but after Troy pointed out how much money we’d be saving by not having to pay for nightly hotel rooms, the numbers didn’t look so bad. In the end, we each agreed to chip in a hundred bucks and share the cost of gas.

To add insult to injury, Tamara’s rental agreement came with a handwritten list of rules and regulations:

No smoking cigarettes or weed inside the van (Tamara was, of course, allergic);

No eating food of any kind inside the van (can you see me rolling my eyes?);

The van must be returned within seven days with the exterior washed and the interior vacuumed (reasonable enough);

Photocopies of both my and Troy’s driver’s licenses must accompany cash payment of the rental fee (just in case the entire trip was an elaborate ruse to kidnap and murder Melody);

And last but certainly not least, Melody Wise—and only Melody Wise—was authorized to drive the van (no sweat off my back; I had no desire to drive that toaster on wheels).

At the bottom of the lined sheet of notebook paper upon which the rules were listed, Tamara had scribbled her name. Directly below, she’d neatly printed each of our names and drawn lines next to them. Melody and Troy had dutifully complied with their signatures. I had not. In a gesture of silent protest, I’d scrawled William Shatner in chicken scratch. For as long as I could remember, Star Trek had been my father’s favorite television show. Either no one noticed what I’d done or they decided not to say anything. Not that it really mattered.

Unbeknownst to the other group members, our photocopy of the rental agreement was currently crumpled into a ball roughly the size of a half-dollar and crammed inside the van’s back seat ashtray.

“I think we should take the Brookshire Road exit,” Troy said from the passenger seat, a Pennsylvania state road map spread out across his lap. He squinted at it and traced a zigzagging route with the tip of his finger. “I like our odds better on the backroads.”

“Quality over quantity?” Melody signaled to change lanes and sped past a pickup truck hauling an open trailer loaded down with lawn equipment. The driver—beard, sunglasses, faded green John Deere baseball cap—gave the van a double take, no doubt wondering how it came to be that such a pretty young woman was chauffeuring around a Black teenager. Probably

thinks it’s a kidnapping in progress, I thought. Watch the idiot pull over at the next rest stop and call the cops.

“Precisely,” Troy said. Oblivious to the truck driver’s stare, he began refolding the map. “The interstate’s too much of a crapshoot. Half the accidents on 83 involve out-of-state victims. No way are we tracking down those families—not in a week, anyway.”

Melody glanced at the rearview mirror. “Exit’s coming up. You okay with Brookshire, Billy?”

“Fine by me,” I said, trying to disguise the fact that my mouth was full of Hot Fries. “Backroads are a lot more camera-friendly, anyway.”

Camera-friendly. Now that was an odd way to put it.

Not for the first time, I wondered if what we were doing might be an exercise in poor taste. No matter how we framed it—and no matter how well intentioned we might be—I had to admit the whole thing was a bit morbid. Maybe my Aunt Helen was right, and it was better to just leave the dead alone. After all, didn’t they deserve their peace? As with the other times doubts had surfaced inside my head, I kept my mouth shut and didn’t say a peep. The documentary had been my idea in the first place, and besides, it was too late to turn back now.

Stealing a peek at the mirror to make sure Melody wasn’t watching, I snuck another handful of Hot Fries into my mouth and began chewing as quietly as possible. The bootleg Van Halen T-shirt I’d bought last summer from an Ocean City boardwalk vendor was covered in a bib of bright orange crumbs. I leaned over and casually brushed them onto the floor, getting rid of the evidence.

Earlier this morning, standing outside Melody’s apartment, she’d flipped a quarter to determine which one of us got to ride shotgun. Troy called heads for the win, and although I’d initially been disappointed, I now believed I’d gotten the better end of the deal. Even with all the gear squeezed into the rear of the van, there was still plenty of legroom to spread out and, best of all, tons of snacks within easy reach. Not to mention, from my vantage point in the back, I didn’t have to serve as copilot and take charge of giving directions.

“For chrissakes!”

As if reading my thoughts, Troy flung the wrinkled mess he’d made of the road map onto the dashboard. “Fifteen-eighty on the SATs and I can’t even fold a fucking—” The wind grabbed at the map and tried to suck it out the open window. “Son of a—” Troy snatched it in midair, crumpled it against his chest like an accordion, and hurled it onto the floorboard, where he pinned it with the heel of his shoe. Before I could manage to get out a word, he spun around and wagged a finger in my face. “I don’t want to hear it, Billy!”

Melody smirked at the rearview mirror and steered off the exit, leaving behind two lanes of northbound traffic on I-83. I leaned forward in my seat, ready to have some fun at Troy’s expense, but at the last moment decided against it. It was too early in the trip to start poking the hornet’s nest. There would be plenty of time for that later. Instead, I replied, “Not saying a word, my friend.” And then I sat back and closed my eyes.

4

At eighteen years old, Troy Carpenter was the youngest of the group—last spring, he’d graduated high school a year early—and also the smartest one in the room. While technically still a freshman at York College, he was already pursuing a double major in accounting and English, and on pace to earn a degree in just three years. If he didn’t end up in the hospital with a bleeding ulcer first. To say that Troy Carpenter was wound up tight was a little like saying the summit of Mount Everest offered a fairly decent view of the surrounding countryside.

I’d once watched Troy practically suffer a nervous breakdown because of a five-dollar parking ticket left on the handlebars of his moped. On another occasion, I’d talked him out of sending his Literature and Sexuality professor a rage-filled, borderline threatening letter because the man had had the audacity to give Troy an 88 on his midterm essay. And I know that being twenty points shy of a perfect SAT score absolutely gnawed at his soul. He drank Mylanta like it was water and chewed antacids as if they were breath mints. He rarely got more than four or five hours of sleep at night. And sometimes, he went all day without bothering to eat.

I genuinely worried about the guy—and yet I had to admit he made an easy target for my hijinks. It was virtually impossible to spend an extended period of time in Troy Carpenter’s company and not be amused and entertained by his idiosyncrasies. He went through more mood swings than a pregnant housewife carrying twins. His bad taste in music (country and western, for God’s sake, the twangier the better) was only rivaled by his horrible fashion sense. He was a die-hard conspiracy theorist, not to mention a passionate believer in both Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster, and had little patience for those who weren’t. The most recent rabbit hole he’d disappeared into involved the rumored existence of a sophisticated network of underground tunnels running all the way from Baltimore City to Washington, DC. Troy insisted that government officials were using these hidden tunnels for nefarious purposes involving the urban drug trade. He’d left numerous messages for reporters at the Baltimore Sun and Washington Post newspapers but had yet to hear back from anyone.

Despite all of this, Troy and I had grown closer as the spring semester progressed. I found myself teasing him less and less, and actually feeling protective of him. Almost like a big brother. He may have been a tornado of anxiety-ridden, hormonal adolescence, but he was also the most authentic and nicest guy I’d ever met. There was no hidden agenda with Troy Carpenter. For better or worse, he was just Troy. And once he finally let me in and I really got to know him, it wasn’t difficult to understand why he acted

the way he did.

“How long… the Appalachians?”

“Depends,” Melody said. “… tomorrow night… don’t stay too long in Sudbury.”

“… the mountains?”

“… grounded in truth… those folks can be odd…”

As I dozed in the warm wash of sunlight slanting through the van window, I overheard snippets of broken conversation. Like listening to a radio station with a weak signal.

“… not dangerous?”

“… talked about that… be fine…”

“… seen a Black person.”

As usual, Troy was worried. After reading a handful of articles discussing the backwoods stereotypes of the Appalachian people, he’d developed an intense dread regarding how we’d be accepted by the locals. “Just look at us,” he’d quipped, staring at our reflection in the grocery store window as we’d stocked up on supplies for the trip. “Toss in a blonde chick, and we’d look like a Benetton ad.” It also hadn’t helped that we’d recently rented the movie Southern Comfort, in which a group of Army Reserve weekend warriors conducting maneuvers deep in a Louisiana swamp are stalked and killed by rifle-toting Cajuns with bad teeth.

“… just in case.”

“… of those are rumors…”

“That doesn’t… me feel better…”

Although he would freely admit to being terrified of snakes, cockroaches, rats, ghosts, and any other number of potential dangers, there existed two great fears in Troy Carpenter’s life. The first was losing his scholarship. As a high school student, he’d attended the prestigious Calvert Hall School thanks to a pair of academic grants provided by the Maryland State Board of Education and an independent alumni council. How else could a third-generation Cherry Hill kid graduate in the top 5 percent of his class from a private Catholic institution with a five-figure annual tuition?

Now, at York College, he was once again riding the scholarship train. Despite only needing to maintain a 3.0 GPA to keep his full ride—and never once coming within spitting distance of dropping below a 3.85—he shuffled his way around campus enveloped within a brewing storm of impending doom. Either he succeeded and made something of himself or it was back to the mean streets of Baltimore, where half the guys he’d grown up with were either.

dead or in prison. The daily pressure of such thoughts was enough to paralyze even the most emotionally balanced of students—something my friend clearly was not.

His second great fear was disappointing his parents. Troy’s father, Raymond, a decorated Vietnam vet and former assembly-line worker out on long-term disability after losing most of his right foot in a factory accident, was the one who’d taught Troy the wonders of literature. Their Hanover Street row house may have been filled with secondhand furniture purchased at parking lot flea markets and the local Goodwill, but the numerous bookshelves lining the walls overflowed with literary treasures—stacks of hardcovers and paperbacks, most of them picked up at various library sales. There was everything from Hemingway to Bradbury, Faulkner to Haley, Joyce to DuBois. The complete works of Langston Hughes and James Baldwin and those from Toni Morrison thus far held special places of honor. A narrow shelf in the second-floor hallway was dedicated to the works of the world’s great poets. Keats and Cummings, Shakespeare and Poe, Whitman and Frost. There was even a crate of old comic books—or “picture books” as Mrs. Carpenter called them—tucked away in the bottom of Troy’s bedroom closet. Star Wars and X-Men; The Incredible Hulk and Classics Illustrated; Tales of the Unexpected and Troy’s all-time favorite, The Fantastic Four. Most of them were missing their covers, but Troy didn’t care. For him, it was the words that mattered the most.

Troy’s mother, Claudia, worked in the cafeteria at nearby Union Memorial Hospital. She was the disciplinarian of the family. All about strict rules and consistent boundaries and tough love—but always with an emphasis on the love. According to Troy, she gave the world’s best hugs. The kind that made you feel safe and strong and like you could fly. Regardless of how old you were. The summer before he’d left for college—while his father was busy playing his weekly game of hearts with friends from the neighborhood—Troy and his mom spent nearly every Saturday evening camped out on the sofa, watching whatever movies happened to be on television. If they were in the middle of a game, they took turns on the Scrabble board during the commercials. In preparation for those nights, they’d stockpile candy from the corner store—M&M’s and strawberry Laffy Taffy for Troy, Hershey’s Kisses and SweeTarts for his mother—and pop a bag of an amazing new snack invention: popcorn nuked in the microwave. Sometimes, if the movie was a long one, one bag wouldn’t be enough, and they’d spoil themselves with a second. Heavy on the butter. Troy didn’t talk about home very often, but when he did, you could really tell how much he missed those Saturday nights with his mom.

Unlike most young men in their late teens, Troy wore his love and devotion for his parents unabashedly on his sleeve. As a result, he took his fair share of mostly good-natured ribbing. At one point, his roommate,

Brent—an alligator-shirt-collar-turned-up preppy from Washington, DC—had started calling him “Mama’s Boy,” but that came to an abrupt halt once Troy began tutoring him in math. Every Sunday night like clockwork, Troy called his folks collect from the pay phone in his dormitory lobby, and at least twice a week, he mailed home postcards with handwritten notes (usually updating them on his class grades and what he’d eaten for dinner that day). So, the mere thought of doing something that might cause them shame or disappointment sent Troy plummeting into an emotional tailspin. It wasn’t until recently, when Troy allowed me to read a journal entry he’d written for his creative writing class, that I finally understood why.

The road was a maze of bloody footprints. It looked like red paint. He’d been running away when the bullets struck. Once in the back of the head, and again in the shoulder. When the police arrived, they covered him with a dirty blanket and wouldn’t let me near him. They shoved me back onto the sidewalk with everyone else. They didn’t care that I was his brother. They didn’t care.

In August 1975, Troy’s eight-year-old brother, Morgan, was the victim of a drug-related drive-by shooting. He had been playing stickball in the street along with a group of friends in front of the Carpenters’ home. These pickup games were a regular occurrence in Cherry Hill, and they often drew an audience. That day, a man named Tyrone Chester—“Big Head” to most everyone in the neighborhood—sat on a nearby stoop to watch while eating his lunch. Chester was a notorious heroin dealer and the intended target of the shooting. Troy was supposed to be there—in fact, whiffle ball had been his idea earlier that morning as he and his brother shared a Slurpee on their walk home from the 7-Eleven—but he’d dozed off on the living room floor while watching TV. The sound of gunshots woke him a short time later. The incident made the front page of the Sun and all four local television news channels, but the shooter was never identified.

In life, the two brothers couldn’t have been more different. Troy was the bookworm, the showman and goofball, comfortable in his own skin. Morgan was quieter, more of an introvert, and the best damn athlete in the entire school. His death had almost broken Mr. and Mrs. Carpenter. In hindsight, if it hadn’t been for Troy, I really believe it would have. During the years following the shooting, he almost single-handedly lifted them up and gave them hope. He stayed clear of trouble in the neighborhood. He volunteered at the humane society and a nearby nursing home. At school, Bs and B-pluses turned into As across the board. He won academic awards and was offered scholarships. Slowly but surely, the sense of doom lifted and the three Carpenters began to feel like a family again.

Troy told us all of this one night at Melody’s apartment, after a breaking news story

about a drive-by shooting in downtown Philadelphia interrupted the episode of Magnum, P.I. we were watching. When he was finished talking, there wasn’t a dry eye in the room. After hearing what had happened to his brother, and especially after reading his journal entry, I realized that all Troy had to do to save his family was place the weight of the world upon his skinny shoulders—at a time in his life when he wasn’t even old enough to vote or buy a six-pack of beer. The pressure he felt on a daily basis had to be staggering.

I’d tried my best on more than one occasion to get him to loosen up. There was an Eddie Murphy concert in Philly, a handful of late nights at the local college bars (try finding a fake ID for a guy who looked like the cartoon owl in the Tootsie Pops commercial), a hike at Codorus State Park, and even a rowdy frat party featuring a pair of live bands. All resulted in rather limited success—the low point coming when Troy vomited all over my brand-new Nikes after downing a single shot of tequila.

A month or so ago, I decided to give him a nickname. A timeless fraternity tradition even though neither of us belonged to one—good-natured in mindset, and maybe I thought it would help him feel more like one of the guys. Initially, I was tempted to call him “Owl”—which was the first thing that came to mind due to his obvious intelligence and the way his glasses magnified his already perpetually wide eyes—but I knew that wouldn’t be well received. Then, I thought possibly “Oscar”—after the New York Yankees outfielder Oscar Gamble, the proud owner of the biggest Afro in Major League Baseball. But when I brought it up, Troy looked at me like I had two heads and said, “Don’t be ridiculous. I’m a Baltimore boy. I want nothing to do with the damn Yankees.” Finally, I ended up settling on “Carp.” A genius move, I thought, a short and simple play on his last name. So far, though, it hadn’t really taken. Not even a little bit. Like I said earlier, what you saw was what you got. Troy was just… Troy.

I wasn’t exactly sure how long I’d been dozing.

I opened my eyes to blinding sunlight streaming through the van window, blinked a couple of times, and then remembered where I was. Groaning, I squeezed my eyes shut again.

Day One. Morning. Or maybe even early afternoon by now. Either way, it was going to be a long-ass week cooped up inside this van. After a while, I forced my eyes open again. Squinted out the window at rolling green hills. A farm pond glistening in the distance. A copse of faraway trees surrounded by cows,

David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” was playing too loudly on the radio. I felt the itch of a headache coming on.

“Do you think he’d been in an accident?”

“Probably,” Melody was saying. “Although he was heading in the opposite direction of the hospital.”

“His bike seemed fine. I didn’t see any damage.”

“I’m just glad I didn’t hit him. Can you imagine if…”

They were talking about the man on the bicycle from earlier this morning. Once we’d finished loading the equipment, Melody went inside to say goodbye to her roommate—a very nice older woman named Rosalita—while Troy and I waited by the van. A few minutes later, she returned carrying a casserole of homemade empanadas. Even covered with Saran Wrap, they smelled delicious. With my stomach grumbling, I took the still-warm-from-the-oven dish from Melody and stowed it inside one of the coolers. And off we went.

I remembered what happened next with the slow-motion clarity of a waking dream:

As we pulled up to the stop sign, Troy swiveled in his seat and looked at me. I could tell he was nervous. His eyes, behind his glasses, were enormous. “Did I ever mention that sometimes I have pretty bad night-mares?”

Melody inched the nose of the van into the intersection. With the radio turned down, I could hear the rhythmic tic-tic, tic-tic, tic-tic of the turn signal. She leaned forward, glanced both ways, and began to make a left onto Margrove Street.

As she did, I answered Troy. “Great, you and me in the same tent. Maybe I should—”

Melody slammed on the brakes—

—as a man on a ten-speed bike zipped right in front of us, missing the van’s front fender by no more than six or eight inches.

Even though he was speeding along, I could make out his details crystal clear. The stranger with the death wish appeared to be in his thirties, maybe early forties. Tall and slender. Receding hairline. Skinny legs covered in coarse, dark hair. He was wearing navy-blue athletic shorts and a plain gray T-shirt. Dark rivulets of what I first believed was muddy perspiration streamed down his neck and chest, soaking the front of his shirt.

But it wasn’t sweat.

It looked like blood.

His face a mask of crimson.

Even his teeth were stained red.

The man was smiling, a macabre full-tooth grin.

And then in a blink—he was gone, swallowed up by the morning traffic.

“WHAT IN THE HELL WAS THAT?!” Melody had practically crawled onto Troy’s lap in an effort to get a better look at the stranger.

“I-I have no idea,” he stammered. “I don’t think… I want to know.”

“Should we go after him?” Melody asked.

“And do what?” I said, still staring out the window.

“I don’t know… maybe try to help him?”

“Yeah, that’s a big fat no from me.” Troy actually crossed his arms over his chest and shuddered. “That dude looked like the devil himself.”

Melody raised her eyebrows. “The devil on a ten-speed bike?”

Before Troy could respond, the driver behind us laid on his horn.

Melody frowned at the rearview mirror. “Yeah, yeah, hold your goddamn horses!”

She checked both ways for cars—and lunatics on bikes—and made a left onto Margrove Street, driving in the direction from which the man had come. Leaning across the seat, I searched the road for a blood trail or signs of an accident but didn’t see anything. Two blocks later, still nothing, and then Melody had to turn right on Logan and merge into a steady stream of northbound traffic. The bloody cyclist still a mystery, we were finally on our way.

The three of us had met five months earlier in Professor Tyree’s American Studies class.

AMST301—as it was listed in the spring 1983 course catalog—was one of York College’s most popular electives. Professor Marcus Tyree, who’d recently celebrated his thirty-second year with the faculty, was highly regarded as both a charismatic and innovative educator, someone who went out of his way to connect with his pupils. His classes invariably attracted the brightest young minds on campus. Melody Wise and Troy Carpenter were exemplary students with sterling track records. They belonged in his classroom. Me, though—Billy Anderson: unheralded sophomore, recovering degenerate, and angst-filled orphan—not so much. The fact that I was enrolled in AMST301 to begin with was nothing short of a miracle.

This was how it happened:

Following a less-than-inspired freshman year—a polite way of saying I’d bombed most of my classes and landed on academic probation—I’d spent the summer of ’82 hauling concrete at a local construction site and taking a couple of night classes to hopefully boost my GPA. When I wasn’t working or going to school, I kept to myself and rarely left my studio apartment overlooking the river. I watched a lot of television that summer. I did newspaper crossword puzzles. I taught myself to play the guitar. Every once in a while, when a restless mood struck, I ventured into the city proper and caught a Phillies game from the cheap seats in left field.

Mostly, I did my best to stay away from the bars. Even at the recklessly young age of

eighteen—with a fake ID purchased for forty bucks tucked away inside my wallet—I’d recognized that my drinking was becoming a problem.

By the time Fourth of July weekend rolled around, the construction gig had given me a perpetually sunburned neck and thick calluses on my palms. I had some difficulty playing guitar, and my medium T-shirts no longer fit. The hard work was good for me, though, and not just because of the newly added muscle. It was good for my soul. In a way, it felt like I was sweating out my demons for eight or nine hours a day. Some of them, at least.

At the end of each week, while the full-timers peeled out of the parking lot in their pickups with paychecks burning holes in their jeans, I was too worn out to follow them into town and get myself into trouble. Weekends were spent sleeping until noon and catching up on laundry. Every Monday afternoon, during my lunch break, I walked across the street to the First National Bank and deposited my check. I didn’t need the money—the insurance payout from my parents’ accident was earning interest in my savings account—but I was proud of myself, none-theless.

I rarely felt lonely or homesick. I actually preferred being alone. It was just easier that way. Most of my old friends from Sudbury had returned from college early that summer. They’d unpacked their suitcases and settled into their old bedrooms and picked up right where they’d left off. Working part-time jobs at the mall or the swimming pool. Hanging out nights at the Scoop and Serve or the drive-in movie theater. Cruising the backroads with six-packs of beer and the radio cranked up or floating downriver on inner tubes. Fishing. Tossing the ball around. Rekindling summer flings.

Just the idea of all that felt like too much work to me. I’d moved away and moved on. I had no interest in looking back or going back—or even trying to stay in touch. Everyone in town had treated me differently after the accident. Overnight, it felt like I’d become a stranger to them. Someone whom folks had a hard time looking in the eye. When I walked into a room, there were stealthy glances and whispers. God, I hated it. I hadn’t even bothered to hook up the phone line when I moved into the new apartment. Who needed it, anyway.

As the summer wore on, my Aunt Helen paid me a number of surprise visits, usually with a back seat full of groceries to restock my pantry. It was good to see her, and a part of me was always sad when it came time to say goodbye. But another part of me—and it would’ve deeply hurt her had she known I felt this way—was filled with relief when I watched her drive away. As much as I loved her, my aunt was a remnant of my other life. A fucking reminder.

Late at night, after her visits, I often found myself unable to sleep, staring at the ceiling, my head ravaged by a tsunami of dark thoughts and bittersweet memories. Those nights felt endless and lost and even a little bit scary, and when I finally did fall asleep, long after the witching hour had come and gone.

I almost always dreamed of my parents.

Still, for a while during that summer, it felt like my efforts were paying off. I managed an A- and a B in my night classes, and by the time students arrived back on campus for the fall semester, my confidence was on the upswing. At registration, I signed up for a full class load of eighteen credits. I was no longer working construction, so I had plenty of time to study. I was steadfast in steering clear of the bars. I signed up for intramural basketball. I even went to visit my Aunt Helen for a long weekend in early October. When midterm grades were posted a short time later, I was shocked to discover that I’d earned four As and a pair of Bs. I must have checked the list at least a half-dozen times to make sure it wasn’t some kind of mistake, and nope, it wasn’t.

Not long after, I ran into Mr. Skelley, my econ instructor, in the cafeteria and he suggested that I might be interested in Professor Tyree’s American Studies class that next semester. Early registration was beginning in a week, he explained with a mouth full of turkey sandwich, and he and Tyree were longtime colleagues and racquetball partners. The class was very popular and usually filled up immediately, but he’d be more than happy to put in a good word for me. Flattered, I thanked him for his generosity, and walked away not really anticipating anything would come of it. I signed up for American Studies 301 early the next week—and to my surprise was promptly accepted.

I still hadn’t made even a semblance of peace with what had happened to my parents—many days I woke up angry and sad and confused—but I no longer felt completely adrift in my life. For the first time since before the accident, I had some sort of direction and focus. I was no longer drinking and was doing a lot better at pushing away the itch. I was sleeping and eating better. Getting a little exercise. There was even a girl in my English class that I kind of liked. I actually began to feel hopeful about what the future might hold.

And then the holidays arrived—and everything went to shit.

VIDEO FOOTAGE

(1:49 p.m., Monday, May 2, 1983)

The classroom is empty.

“Testing… one… two… three… four… five…”

As the camera swings around in a slow circle, we see a dozen rows of desks and chairs stretching from the front of the room to the rear. Five or six in each row. It’s a narrow room. The walls covered with maps and charts and indexes. A large metal desk sits center stage at the front. Behind it, a length of chalkboard covered in messy handwriting. An exit sign hangs above the only door, which is closed.

“… six… seven…

eight… nine… ten.”

The image blurs and then quickly sharpens again as the camera operator zooms in on the blackboard. ROANOKE and CROATOAN and 1590 swim in and out of view——

——and then we hear a door bang open off-screen.

And a loud, boisterous voice. “Billy! I am so sorry to interrupt!”

The camera abruptly shifts to the left——and a grizzly bear of a man comes into focus. Professor Marcus Tyree is wearing a huge smile above his unmanageable beard and carrying a stack of books in his arms. He walks to the large desk at the front of the room and puts them down with a thud.

“No problem, Professor. Just giving the camera a test run. This thing’s pretty amazing.”

“The A/V department to the rescue.” He sits down behind the desk——and we hear the chair groan beneath his weight. “Glad it worked out for you.”

“Thanks to your help.”

“Happy to put in the good word… although I admit I’m still a bit worried about the three of you going on the road by yourselves.”

“Don’t be. It’ll be fun.” As Billy walks closer, we get a shaky glimpse of the professor’s tattoo-covered forearms. “Melody’ll watch over me, and I’ll watch over Troy.”

“And who’ll watch over Melody?”

“That girl can take care of herself, believe me.”

And then they’re both laughing.

10 At York College, the last day of exams before Christmas break was Tuesday, December 21. I had an 11 a.m. British Lit final—and that was it. Semester officially over. I finished my blue book essay on Emily Brontë in just under an hour and walked outside to a winter wonderland. A steady, wet snow was falling from a slate-gray sky. The ground was already covered, and the mostly abandoned campus resembled a New England postcard. As I walked to my car, I listened to distant laughter and cries of joy coming from a handful of sledders on the hill in front of the library and a gang of grade-school kids waging a snowball fight across the pond. Another week or two of this frigid weather, and they would be ice-skating and playing hockey. When I pulled out of the parking lot with “Silent Night” playing on the radio, it felt like I was driving inside of a snow globe. Thrilled to be finished with my exams, I spent the rest of the afternoon Christmas shopping. Later that evening, I went out for pizza and beers with the guys from my intramural basketball team. It was the first time all season that I’d accepted an invitation to join them. When the waitress asked for my drink order, I told her a

pitcher of Sprite. No one at the table said a word about it.

When I got back to my apartment later that night, I wrapped the only two gifts I’d purchased. A silver necklace and a set of carving knifes. Both for my Aunt Helen. I wasn’t sure if she’d like what I’d picked out, but I figured she could wear the necklace to church if she wanted to and use the knives to cut up the vegetables she grew in her garden. I’d agreed to spend Christmas week at her house in Sudbury and was actually looking forward to it.

I left the wrapped presents on the kitchen counter beside my keys, poured myself a glass of water from the tap, and got ready for bed. Once I was settled beneath the covers, I turned on the television. White Christmas was playing on cable. I immediately felt a lump form in the back of my throat. This was my mother’s favorite movie. Growing up, we’d watched it as a family at least a dozen times. Probably more. She always made hot chocolate with tiny marshmallows and turned off the lights so it felt like we were at the movie theater.

On the TV, in my dark bedroom, Bing Crosby and Danny Kaye, both dressed in makeshift hula skirts, began dancing across the screen, crooning about devoted sisters…

… and for just a moment—as clear and present as if she were sitting right next to me—I heard my mother’s voice singing along with them.

It should have made me happy.

It should have made me remember.

And smile.

But it didn’t.

Instead, my heart broke into a million pieces.

All over again.

And then it was as if all the hope and goodwill and progress that had been stored up inside me those past few months bled out of my body in one great arterial gush.

Leaving behind nothing at all.

Except for tears.

I lowered my head and let them come.

Before long I was sobbing—and couldn’t stop. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...