- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

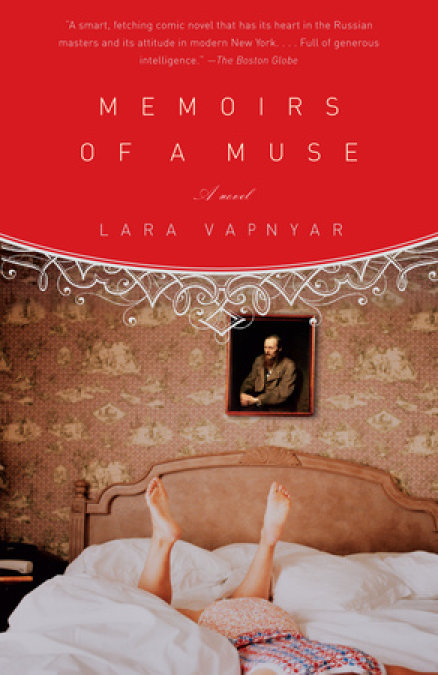

Tanya is a typical teenager living with her bookish professor mother in a cramped Soviet apartment. She is obsessed with Dostoyevksy, and noticing that he always portrays his mistress and muse in his novels–never his wife–she determines to become a companion to a great writer. Her opportunity comes when, as a college graduate newly emigrated to America, she attends a Manhattan bookstore reading by Mark Schneider, a Significant New York Novelist. Tanya quickly moves in with Mark, ready to dazzle in bed, to serve and inspire . . . if only he would spend a little more time writing. But as she struggles to better understand her role as Muse, Tanya also learns more than she expected about the destiny she has imagined for herself.

A touching and very funny novel in the great tradition of Russian realism, Memoirs of a Muse is also a lively meditation on the mysteries and absurdities of artistic inspiration.

Release date: December 18, 2007

Publisher: Vintage

Print pages: 224

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Memoirs of a Muse

Lara Vapnyar

The woman is young, with a broad, well-defined face framed with heavy waves of auburn hair. Her lips are squeezed tight. Her small eyes are intense, alert. She is watching the man. The man is in his forties, short, heavy, with a scant beard and a lumpy bald patch, visible to the woman because his head is hung low. He has sinewy hands and the prominent forehead of a great Russian writer.

He is, in fact, a great Russian writer. He is Fedor Dostoevsky. And the woman is Apollinaria Suslova, his lover. Or his former lover, because she has just informed him that she has fallen in love with somebody else.

He is kneading his face with his hands. His large thumbs are stretching the skin on his cheeks, his index fingers are pressing into his temples. Beads of sweat form between the rare hairs on his crown and crawl down, lingering in every wrinkle on his forehead. Some of them dissolve in his skin, others make it as far as his brows, only to be crushed by his fast, cruel fingers. Two blue veins throb on his forehead. He is suffering. She can’t take her eyes away.

“Polya,” he suddenly whispers. He raises his wet, shaking face to meet her eyes. “Have you given yourself to him? Have you given yourself completely?”

His voice is thin, hysterical. She recoils. Even now, now! That is all he could ever think about.

“I won’t answer that,” she says.

“Oh!” he groans. His head drops back and his fingers resume their frenzy.

She stretches her legs under the table. She’d never imagined that inner turmoil could take such a physical form. She can smell the heavy odor of his sweat, she could reach with her hand and feel his veins throb under her fingers, she could taste his tears. She could take him into her arms and let her body shake with those powerful convulsions of his.

She doesn’t budge.

“Cruel, coldhearted, unkind,” people called her.

Dostoevsky was one of them. “She desperately wanted and tortured herself to become somewhat kind,” he wrote about one of his heroines, one of many inspired by Polina.

So was it true? Was she cruel? Does a muse have to be cruel? Does a muse have to be able to induce a certain amount of pain? I want to know that.

I want to know why I failed.

“Here, I see the brilliant, wondrous future spread out for both of you,” the old governess said to little Polya and her younger sister, Nadya, pointing to the coffee cups with her clean, chubby hand. She had seated the girls around the big, empty table and placed a coffee cup in front of each of them. Polya climbed onto the seat of her chair and peered into her cup. The dim candlelight made their plump, round-faced governess look like a mysterious sibyl.

“You see that? See that?” the governess said, pointing at the barely visible holes and furrows in the grounds in Nadya’s cup. “Our Nadya will be a heroine, a conqueror. She will fight for a great cause, she will reach unreachable heights.”

Nadya nodded—she saw the furrows.

“Now, let’s look at yours, Polya.” Polya licked her parched lips. “I see Polya as a great beauty and as a great conqueror too, but she will conquer men’s hearts and inspire them. She will be a muse.”

Later Polya sobbed in her bed, pounding on the mattress with her little fists. She saw a muse as a lapdog with a devoted expression in her wet, bulging eyes. She wanted to be a heroine. She didn’t want to be somebody’s lapdog!

That scene about the governess I made up. I’m not sure that the sisters even had a governess. But I know that Apollinaria’s younger sister, Nadezhda, achieved great success: as the first Russian medicine woman, as an accomplished writer, as a political activist, as a wife. While Apollinaria . . . Apollinaria failed at just about everything she attempted. She failed as a scholar. She failed as a teacher. She failed as a writer. She failed as a wife. What else? Oh, yes, she failed as a lover; she failed as a lover several times.

Apollinaria Suslova didn’t succeed at anything, except immortality. But what good has immortality ever done anyone?

As a child, I used to think that Dostoevsky’s muse was his second wife, Anna Grigorievna. I knew her story before I knew anything else about Dostoevsky, before I’d read any of his books.

When I was three, my father left to marry a tall, square- shouldered woman named Marina; shortly after that, he died. To my mother and me it was a kind of double betrayal. Around that time, photographs of the major Russian writers began to line the wall in my mother’s room, replacing pictures of my father.

I never liked Tolstoy’s portrait—he looked like a mean Santa Claus, the one who won’t bring you anything good, the one who would leave a knitted scarf or a pair of socks under the tree. The existence of a mean Santa Claus was one of my early beliefs. There were two Santas, two brothers. The good one left glossy boxes with dolls, dolls’ furniture, or dolls’ dishes for me. The mean one left nothing but clothes—a huge waste. My mother would’ve bought me clothes anyway.

I didn’t like Chekhov’s portrait either. There was something suspicious about his grin and his pince-nez. What if he knew something that I didn’t want him or anybody else to know? What if he even knew about my aunt’s favorite vase, which I accidentally broke, disposing of the shards and then pretending not to know anything about it? I definitely didn’t like Chekhov!

Pushkin . . . well, Pushkin was okay. He seemed to be a nice guy, but he didn’t look serious enough for a writer.

Dostoevsky was the one whom I loved. He had strong hands and a large forehead, so large that it seemed to burst through his skin. He had serious eyes, and he looked straight at me, without hiding, without the fake playful expression of other adults. “Dostoevsky had different eyes,” my mother said when she spotted me staring at him. “One brown and one black.”

“Different eyes!” I repeated, awestruck, and asked if he had a wife. “He is dead” was the answer. “But he did have a wife, when he was alive. Her name was Anna Grigorievna.”

I liked her name. “Was she nice?”

“Oh, yes, she was very nice. She took very good care of him.”

“I could do that too!” I said.

I imagined Dostoevsky sharing a dinner table with my dolls. I knew how to prepare kasha for dolls and serve them tea. I would’ve spread a napkin on his lap and fed him my kasha, then I would’ve put him to bed, tucked his blanket around him and taken his temperature with my toy thermometer, just in case.

Dostoevsky stayed for me a dead writer with different eyes and a nice wife up until I turned ten and my grandmother got sick. Then I learned some more details about his life.

“Dostoevsky’s name was Fedor Mikhailovich, and so was your grandfather’s! Dostoevsky was crazy, but your grandfather even more so!” My grandmother told me this as I stood cutting her hair. I had no experience cutting hair, except for chopping up the coarse ringlets of my dolls’ curls.

My grandmother’s hair was white with a faint tint of yellow, light and slippery in my fingers. She’d always worn it in a neat chin-length cut with a thin blue band to keep the bangs from falling over her eyes. After the first few months she spent bedridden, her hair barely reached her shoulders, like feeble thawing icicles. She complained that long hair made her neck itchy, she complained that it made her hot, she complained that she looked like Robinson Crusoe. I said that she would need a beard to really look like Robinson Crusoe. I said that she’d better stop complaining. I said, “Enough, Ba.” But she kept insisting on a haircut.

“You should try it,” my mother said to me. “You’re good with your hands.”

My hand skills had only recently been discovered. Just a few weeks before that, I’d fallen victim to severe rainy-day boredom and pulled an old (probably left from my kindergarten days) box of white clay out of the closet. I sculpted a fat, curly sheep, hardened it in the oven, painted it off-white, sheep color, and presented it a week later to my uncle for his birthday.

“Oh, we have hands, don’t we?” my aunt Maya commented. Up until that moment it was thought that my mother and I were equally bad at all hands-involving activities: sewing, knitting, cooking, making sheep out of clay. I stood in front of Maya, staring at my hands as if they’d been slowly coming out of nonbeing. I had hands!

Having hands saddled me with new duties. I was to be the one to cut my grandmother’s hair.

I moved a chair to the edge of the bed, sat my grandmother up, and slowly dragged her from the bed and onto the chair’s seat, holding her under the arms. She looked weightless, but felt awfully heavy. After those months in bed she seemed to have lost all the substance that used to fill the space between her bones and her skin. I imagined she was completely empty in there, her bones rattling inside of the withered sack of her self, like my wooden building blocks in their canvas bag. I wrapped a sheet around her neck, untied her blue band and combed her hair, trying to avoid touching her scalp. Her skin, though warm, had a corpselike softness about it. I felt that if I pressed my finger hard enough, it would break her skin and fall into some deathly depths that reached further than the inside of my grandmother’s body.

I took the scissors—large stainless-steel shears, usually used for cutting fabric and trimming fish tails—and snapped with them a couple of times, then put them down and combed her hair some more. Her eyes, wet and alert, took in the scissors, the comb, my hands, and seemed to creep into my face.

“Sit still, Ba,” I said, turning away from her stare. I called her a short and intimidating “Ba” instead of a long “Babushka.” I loved to bully her. “Sit straight, Ba, you don’t want to spill your soup.” “Here is your potty. You better do it now, because I have lots of homework and I’m not going to run in here every second.” She never complained. She moved the way I told her to. She tried to eat as fast as possible and to go to the bathroom as neatly as she could. She praised the food I served. She sang to me. She told me stories. She met me with an eager smile. She tried to humor me.

Tough but efficient, I thought myself a perfect nurse.

“You wouldn’t believe what this girl of ten can do. I’ve been training my nurses for years and they are not half as accurate or reliable,” my uncle said, introducing me to his doctor friends, who shook their heads in disbelief and smiled at me. I knew I was special! I’d always known! No other girl of my age could take blood pressure, run an ECG machine, or administer injections. Not even my uncle’s daughter, Dena. Dena, who was nine years older than me, a very good student, perfect in every way, and preparing to go to the U.S. There was no saying what I would be able to do when I got older!

It was only years later, when the doubts started gnawing at me, that I thought very few girls of ten were ever assigned to giving injections or running echocardiogram machines, and if they were, they might have done no worse than me.

And still later, a sickening suspicion suddenly crept in: my grandmother was so smiley and acquiescent not because I was a perfect nurse, but because she was afraid of me.

Before her stroke my grandmother had lived in her own apartment “a half of Moscow away from us,” as my mother had said. We visited her once a month. To get to her part of Moscow we had to switch from a bus to a subway and then to another bus. The trip back and forth took us more than two hours. I thought that the hour spent at my grandmother’s place wasn’t worth it. She always served us cake that I hated—a stale, crumbly sponge smeared with sour cream and bitter wild strawberry jam, and she kept asking if I’d at last learned how to make my bed and spread my bread with butter. My grandmother’s apartment didn’t have any toys, or any fun or beautiful objects—only books, which lay everywhere with neat paper bookmarks stuck between the pages, and a few photographs: of my dead grandfather, my uncle, my mother, and myself at the age of two. I would rather she had a more recent photo. She talked about her health, the problems she encountered while paying her electricity bills or applying for her special war widow pension, the sidewalks covered with thin ice in the mornings. My grandmother often attempted to talk about my father, but seemed unsure if she should weep over his tragic, untimely death or condemn his behavior when he was alive, so she switched to my uncle’s wife, Maya, who was not dead and thus not protected from criticism.

My grandmother had a stroke on her seventieth birthday. We came to her door smartly dressed, with a cake, a bottle of Soviet champagne, a knitted shawl, which my mother had bought because she couldn’t knit, and the birthday card, which I had decorated with stickers because I couldn’t draw. My uncle was to join us later. We rang the doorbell, then we knocked, then my mother pulled the keys from her purse and told me to stay on the staircase. In a few seconds, I heard her scream. She ran out of the apartment, grabbed me by the sleeve, and dragged me to the next-door apartment. A short, chubby woman opened the door and took me in after my mother whispered something into her ear. Inside, a fat man in a white tank shirt was eating his dinner in front of the blaring TV. “Are you hungry, my little chick?” the woman asked me. I shook my head and went back to the front door, where I flattened my face against the cold wood of the door’s surface and watched through the peephole what was happening on the staircase. Nothing happened for a long time. Then I saw my uncle and people in white gowns running up the stairs. My mother was crying and shaking when she opened the door for them. In a few moments I saw my grandmother strapped to the stretcher. My mother ran down the stairs after the stretcher, trying to throw the knitted shawl over my grandmother’s legs. That means she is alive, I thought, wiping the tears away from my eyes so I would be able to see. There is no need to cover the legs of a dead person.

“She’ll be home soon. It was just a mild stroke,” my mother told me later. “She’ll just have to live with us now. She really is fine.”

The chilling preparations for my grandmother’s arrival made me doubt my mother’s words. A big bed was installed in the living room. A waterproof sheet was carefully tucked over the new mattress and covered with a regular sheet. Then my uncle came with a special chair he had made in his garage. You could remove the chair’s seat, place a potty under, and there, you had a toilet. He raved about his creation. “Eh? What do you say? After she’s done, you can put the seat back and use it as a table for her meals.”

“A table?” my mother gasped. “A table! On the same chair, where she . . .”

“So what? The seat is removable, right? Anyway, I talked to Mother and she didn’t mind.”

I wondered what had happened to my squeamish grandmother. If she didn’t mind taking her meals on the toilet, she couldn’t possibly be fine.

She looked fine, though. She looked the same, I decided when I came home from school on the day of her discharge from the hospital and saw her in the new bed. She was pale, and she’d lost some weight, and she wore a nightgown instead of her usual dress, but she smiled and talked and made sense when she did. “The food in the hospital wasn’t as bad as I’d expected. Yesterday they even served cream puffs, and I wanted to save one for Tanechka, but they didn’t allow me,” she said. My uncle spent some time teaching my mother how to remove the chair seat and how to move my grandmother onto it without having to lift her. My mother practiced a couple of times. My grandmother didn’t protest. Then we all had tea in the living room so my grandmother wouldn’t feel left out. She had some tea too, leaning over the new chair.

“I want to see my little girl,” my grandmother requested the following morning. I walked up to her, but she shook her head. “Who is that?”

“This is Tanya,” my mother said. “Our little girl.”

My grandmother laughed. “You two think you can deceive me like that? Our Tanya is no more than two or three and she doesn’t look like this one at all. You think I won’t know the difference? You think I went funny in the head?”

It was stupid of me, but I ran out and locked myself in my room and said that I wouldn’t come out. “She has crazy eyes!” I yelled through the door. “Wet and crazy!”

“A stroke has everything to do with food,” my uncle explained to me on the phone. “The brain is usually fed on blood. After a stroke the brain isn’t fed properly, and that causes all kinds of disturbances. That’s why your grandmother might fall when she walks, and that’s why she has memory lapses, and that’s why, well . . . you see, that’s why she sometimes doesn’t have a clear mind.”

Her brain wasn’t fed properly. I understood that my uncle was talking about the quantity of blood, that the brain didn’t get enough. But I imagined that my grandmother’s brain was getting junk food, and thus producing junk.

“As improbable as it sounds,” my uncle added, “the state of her mind won’t stay the same. It can change from better to worse and back. Hopefully it will change back. Just remember that she is not crazy, it’s just a question of brain food.”

I decided I wasn’t afraid of her anymore.

The schedule of caring for my grandmother was established. My mother was to switch to an afternoon shift at work, and would be at my grandmother’s side in the mornings and late nights. My hours were from two to eight p.m., after I came home from school and before my mother came from work. And my uncle promised to visit whenever he had the time, a statement met with a sarcastic grin from my mother’s side.

“I’m home, Ba!” I yelled when I opened the door with my key upon returning from school. I dropped my schoolbag on the floor and marched into the room, ready to check on the patient, who was to be in my power for the next six hours. Her mental state was the first thing I checked on. My uncle was right; it wavered back and forth. At times she didn’t recognize anybody. She pushed me away and said that her granddaughter was a little girl and asked what we had done to that little girl. She took my mother for her late sister, Zeena. She read her books upside down. She called for Hitler and Shakespeare. “Hitler, Hitler, help me die,” she sang in her tiny voice. Why Hitler? we wondered. Was she thinking about the Jews and, having suddenly regained her Jewish conscience, wanting to share their fate? No. She said that she wanted him to poison her the way he had poisoned himself and Eva Braun.

Then she would sing for Shakespeare. I asked if she needed Shakespeare to kill her off the way he had killed off all his tragic characters. But I was wrong again. She needed Shakespeare, she said, to record her story. Why Shakespeare, of all writers? She didn’t give an answer to that. After her quest for Shakespeare, she usually sneaked out of the bed and wandered off with a pillow under her arm, swaying on her thin and dry spaghetti–like legs. I felt that it was really her poor underfed mind that left her body and went wandering with a pillow under its arm.

Then her mind would return to her. She would lull herself to sleep singing of Hitler and Shakespeare and wake up with a clear mind. She would look around her in disbelief, slowly taking in the room, the bed, the nightstand with its colorful disarray of medicine bottles, the chair with its removable seat. She would peer into our faces and say that she was sorry, so sorry to be a burden. She would grab my mother’s or my hand when we approached the bed and beg us to say goodbye to her now, because she was afraid that one day her mind would go and wouldn’t return. My mother would hold her hand and say goodbye to her, even though she’d already said it the day before, and the week before. But I refused to do that—I’d run into my room and slam the door.

Fortunately her sane days weren’t frequent. For the most part her mind drifted in a weird, transitional state that I called “medium-crazy.” Her mind was almost clear: She didn’t confuse our names, she didn’t attempt to wander off or eat soup with a fork. She behaved like a proper invalid: subdued and grateful with me, weepy and whimsical with my mother. Still, something betrayed the sickness of her mind to those who knew her well. It was her passion for storytelling, the unhealthy vigor that didn’t let her rest, that made her talk abruptly, confessionally, that made her greedy for an audience. My late grandfather, a man we avoided in family conversa- tion, was the main hero of her stories. He, and another Fedor Mikhailovich: Dostoevsky. Both men emerged as bright and sinister characters, as fairy-tale villains, endowed with juicy real-life details.

“Do you know how it came about that I married your grand- father? He forced me!”

Forced her? Nobody’d ever talked to me about that! I was all ears.

“A fat chance he would’ve married me, if not for the Revolution. I came from a good family. And he was . . . He was . . . He didn’t have a spare pair of pants to cover his . . . his male belongings!”

I couldn’t believe nobody was there to stop my listening to this. I hadn’t known much about my grandfather. He died shortly after I was born, and whenever somebody was around to talk about him in my presence, my mother sent the person a warning look, and he or she hurriedly changed the subject. My grandfather was a Communist and a war hero—that much I knew because I had often heard my mother plead to social workers, “My father was a member of the Communist Party for thirty years, he defended Stalingrad, he has two medals of honor—you can’t just cut his wife’s pension.” He was a handsome man; he looked like a thirties movie star in photographs, with a big lock of hair on his forehead, brilliant eyes, and a powerful jaw. At various times in his life he worked as a full-time reporter, a freelance photographer, a wine taster, an assistant to a judge, a vegetable store manager, and an amateur theater critic. (The last in the list was based on the acid letters he liked to send to newspapers whenever he disliked a play.) When I asked why he switched jobs, I was met with that wary look on my mother’s face. I knew that he loved me very much. “Your grandfather was so happy when you were born that he promised to stop drinking and actually didn’t drink for eight months,” my uncle managed to tell me once, before my mother silenced him with her stare.

My grandfather was also a revolutionary. “A first-class revolutionary! A Communist, a proletarian, a top student in a political awareness school! I met him at just the right time,” my grandmother said. “You see, my father used to own a tiny grocery store before the Revolution. And he was labeled a capitalist and an enemy of the people. We needed clean documents, we needed proof of residence . . . Your grandfather promised to help. I married him fictitiously. Fictitiously! But you know what he did? After a couple of days he just climbed into my bed and said that fictitious marriages were against the Soviet law, and he, as a Communist, couldn’t possibly break the law!”

“So, what happened next, Grandma?”

“What happened next? What could happen next? He went on proving the truth of our marriage every night, sometimes twice a night. Sometimes three times!”

I didn’t mind my grandmother’s “medium-crazy” state at all! The only thing that bothered me was her eyes. I did what I could to avoid looking at her. Her eyes chased me. They were ready to seize me whenever I slipped and looked up at her. Then her face bloomed into a smile—half sly, half delirious.

Such was her state on the day I cut her hair. “Dostoevsky, note it—also Fedor Mikhailovich, just like your grandpa—was a terrible, terrible man,” she said as I reached for the scissors.

“Now sit still, Ba,” I ordered as her body tilted to the side of the bed.

“How he tortured his poor wife! His muse! She was his muse, you know. Without her he wouldn’t have written shit.”

“I know her name. Anna Grigorievna,” I said.

“Anna Grigorievna. That’s right. Oh, how he tortured her!”

“Damn! I told you to sit still!” I said as her body tilted to the other side. It wouldn’t be such a big deal if she fell onto the bed, I thought, but I knew only too well how those waiflike limbs turned into dumbbells as soon as you had to pick her up. A cream-colored knitted shawl, which my grandmother liked to wrap around her legs, not so much for warmth as for its softness, drew my attention.

“I am going to tie you up, Ba. If you want to have a haircut, I’ll have to tie you up.” She didn’t resist while I circled around her with the shawl, weaving it between the chair back’s rails and under her breasts, then tied it in a big knot between her shoulder blades. She sat as still as she could, nodding eagerly, following my hands with restless, glistening eyes.

“Better? Isn’t it?” I asked my prisoner and took the scissors off the nightstand.

The first snap was a signal for her to continue the story.

“Fedor Mikhailovich would take all the money and gamble it away, and then he would come back for more—but there wasn’t any—and pawn all of the good things only to gamble the money away. He gambled away her ring, her earrings, her shawl, and once even her shoes and her dress, so she couldn’t even go shopping.”

“What was the point in going shopping if he’d already gambled away all the money?”

“Well, maybe she hoped to ask a nice salesman for credit, or just wanted to window-shop. . . . And when he came back, instead of apologizing he yelled at her for not fixing his supper on time!”

“Did she yell back at him?”

“Never! She apologized for not fixing supper. You see, she was a very good wife.”

“All right, now shut your eyes.”

I let her long bangs fall down on her forehead and snapped the scissors there, careful not to scratch the skin. It was easier to look at her when her eyes were closed. She looked relaxed, smoother, more alive, almost normal, until one sly, glistening eye opened under my snapping hand.

“Geniuses are a crazy lot. They’re crazy like hell! You never know how to please them. You think that you do. You keep track of the things that please them. But they are fickle, they change their likings on a whim. You serve them tea with sugar and cream—their favorite, and you had just gone out specially to buy that cream—and they yell that they wanted coffee with lemon. You want to throw that tea into their red, ugly mugs and then break t

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...