- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

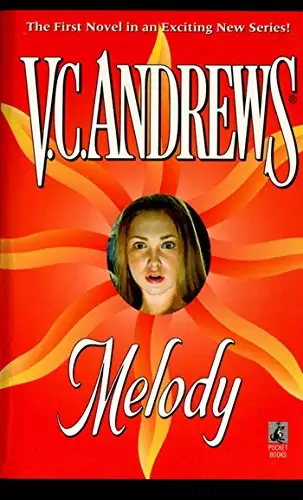

Synopsis

Melody Logan knew her beautiful mother, Haille, was unhappy in their hardscrabble mining town.... But with her wonderful father's unwavering love, Melody always felt safe -- until a dreadful mine accident ripped her from her family's moorings. She was still devastated by her father's death when she left West Virginia with Haille to follow her mother's dream of becoming a model or actress. But first they stopped in Cape Cod to visit her father's family at last. Melody knew only that her grandparents had disowned their son when he married Haille -- just because she was an orphan, her mother said. Yet moments after Melody first laid eyes on dour, Bible-spouting Uncle Jacob, nervous Aunt Sara, and her cousins -- handsome Cary, whose twin, Laura, had been killed recently in a sailing accident, and sweet, deaf little May -- Haille announced that Melody was to live with them. Sleeping in Laura's old room, Melody was awash in a sea of grief and confusion, with only her beloved fiddle to comfort her. Then Cary revealed the truth he'd gleaned about her parents -- a sad shocking story that only puzzled her more. Melody knew nothing of the dark deceptions that would soon surface...the devastating betrayals she would face before she glimpsed the faint, beckoning lights of a safe harbor....

Release date: February 8, 2011

Publisher: Pocket Books

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Melody

V.C. Andrews

I think as soon as I was old enough to understand that Mommy and Daddy were having serious arguments, I felt like an outsider, for if I appeared while they were having one, both of them would stop immediately. It made me feel as if I lived in a house with secrets woven into the walls.

One day, I imagined, I would unravel one of those secrets and the whole house would come down around me.

Just a thought.

But that is exactly what happened.

One day.

Chapter 1: The Love Trap

When I was a little girl, I believed that people could get what they wished for if they wished hard enough and long enough and were good enough, and although I'm fifteen now and long ago stopped believing in things like the Tooth Fairy, Santa Claus, and the Easter Bunny, I never completely stopped believing there was something magical in the world around us. Somewhere, there were angels watching over us, considering our wishes and dreams and occasionally, when the time was right and we were deserving, they granted us a wish.

Daddy taught me this. When I was still small enough to sit comfortably on his muscular right forearm and be carried around like a little princess, he would tell me to close my eyes really tight and wish until I saw my angel nearby, her wings fluttering like a bumble bee.

Daddy said everyone had an angel assigned to him or her at birth, and the angels did all they could to get humans to believe. He told me that when we are very little it's much easier to believe in things that grown-ups would call imagination. That's why, when we're little, angels will appear before us sometimes. I think some of us hold on a little longer or a little harder to that world of make believe. Some of us are not afraid to admit we dream even though we're older. We really do make a wish when we break a chicken bone or blow out our birthday candles or see a shooting star, and we wait and hope, even expect that it will come true.

I did so much wishing as I grew up, I was sure my angel was overworked. I couldn't help it. I always wished my daddy didn't have to go down into the coal mines miles under the earth, away from the sun in damp, dark caverns of dust. Just like every other coal miner's child, I had played in the openings of the deserted old mines, and I couldn't begin to understand what it would be like going down deep and spending a whole day below the fresh air. But poor Daddy had to do it.

As long as I could remember, I wished we lived in a real house instead of a trailer, even though right next to us, living in their trailer, were Papa George and Mama Arlene, both of whom I loved dearly. When I wished for a house, I just added a little more and wished they would live in the house next to ours. We would both have real backyards and lawns and there would be big maple and oak trees. Papa George would help me with my fiddling. And when it rained hard, I wouldn't feel as if I were living in a tin drum. When the wind blew, I wouldn't fear being turned over and over while asleep in my bed.

My wish list went on and on. I imagined that if I ever took the time and wrote all the wishes down, the paper would stretch from one end of our trailer to the other.

I wished hard that Mommy wasn't so unhappy all the time. She complained about having to work in Francine's Salon, washing other women's hair and doing perms, even though everyone said she was an excellent hairdresser. She did enjoy the gossip and loved to listen to the wealthy women talk about their trips and the things they had bought. But she was like a little girl who could only look in the window at beautiful things, one who never got to buy any of them herself.

Even when she was sad, Mommy was beautiful. One of my most frequent wishes was that I would be as pretty as she was when I grew up. When I was younger, I would perch in her bedroom and watch her at her dressing table meticulously applying her makeup and brushing her hair. As she did so, she preached about the importance of beauty care and told me about all the women she knew who were attractive but neglected themselves and looked simply awful. She told me if you were born pretty, you had an obligation to look pretty whenever you were in public.

"That's why I spend so much time on my hair and my nails, and that's why I have to spend so much money on these special skin creams," she explained. She was always bringing home samples of shampoo and hair conditioners for me to use as well.

She brought home perfumed bath oils and would soak in our small tub for over an hour. I would wash her back or, when I was old enough to be trusted, polish her toenails while she manicured her fingernails. Occasionally, she did my toenails and styled my hair.

People said we looked more like sisters than mother and daughter. I had inherited her small facial features, especially her button nose, but my hair was a lighter shade of brown, hair the color of hay. Once, I asked her to dye my hair the same shade as hers, but she shook her head and told me to leave it be, that it was a pretty color. But I wasn't as confident about my looks as she was about hers, even though Daddy told me he rushed home from work because now he had two beautiful women at home waiting for him.

My daddy stood six foot three and weighed nearly one hundred and ninety pounds, all muscle from working in the mines so many years. Although there were times when he returned home after a very long day in the mines aching, and moving slowly, he didn't complain. When he set eyes on me, his face always burst out with happiness. No matter how tired those strong arms of his were, I could run into them and he'd lift me with ease into the air.

When I was little, I would anxiously wait for the sight of him lumbering up the chipped and cracked macadam that led from the mines to our home in Mineral Acres trailer park. Suddenly, his six feet three inches of height would lift that shock of light brown hair over the ridge and I would see him taking strides with those long legs. His face and hands would be streaked with coal dust. He looked like a soldier home from battle. Under his right arm, clutched like a football, was his lunch basket. He made his own sandwiches early in the morning because Mommy was always still asleep when he woke and got ready for work.

Sometimes, even before he reached the Mineral Acres gate after work, Daddy would lift his head and see me waving. Our trailer was close to the entrance and our front yard faced the road from Sewell. If he saw me, Daddy would speed up, swinging his coal miner's helmet like a flag. Until I was about twelve, I had to wait close to Papa George and Mama Arlene's trailer, because Mommy was usually not home from work yet herself. Many times, she would go someplace and not make it home in time for dinner. Usually, she went to Frankie's Bar and Grill with her co-workers and friends and listened to the juke box music. But Daddy was a very good cook and I got so I could do a lot of the cooking myself, too. He and I ended up eating alone more times than not.

Daddy didn't complain about Mommy's not being there. If I did, he urged me to be more understanding. "Your mother and I got married too young, Melody," he told me.

"But weren't you terribly in love, Daddy?" I had read Romeo and Juliet and knew that if you were desperately in love, age didn't make a difference.

I told my best friend Alice Morgan that I would never marry anyone until I was so head-over-heels in love I couldn't breathe. She thought that was an exaggeration and I would probably fall in love many times before I was married.

Daddy's voice was wistful. "We were, but we didn't listen to older, wiser heads. We just ran off and eloped without thinking about the consequences. We were both very excited about it and didn't think hard about the future. It was easier for me. I was always more settled, but your mother soon felt she had missed out on things. She works in that beauty parlor and hears the rich ladies talking about their trips and their homes and she gets frustrated. We got to let her have some freedom so she doesn't feel trapped by all our love for her."

"How can love trap someone, Daddy?" I asked.

He smiled his wide, soft smile. When he did that, his green eyes always got a hazy, faraway glint. He'd lift his gaze from my face to a window or sometimes just a wall as if he were seeing images from the mysterious past float by. "Well...if you love someone as much as we love Mommy, you want her around you all the time. It's like having a beautiful bird in a cage. You're afraid to let the bird free and yet you know, it would sing a sweeter song if it were."

"Why doesn't she love us that much, too?" I demanded.

"She does, in her own way." He smiled. "Your mother's the prettiest woman in this town -- for miles and miles around it too -- and I know she feels wasted sometimes. That's a hard thing to live with, Melody. People are always coming up to her and telling her she should be in the movies or on television or a model. She thinks time's flying by and soon it will be too late for her to be anything else but my wife and your mother."

"I don't want her to be anything else, Daddy."

"I know. She's enough for us. We're grateful, but she's always been restless and impulsive. She still has big dreams and one thing you never want to do to someone you love is kill her dreams.

"Of course," he continued, smiling, "I have every reason to believe you're going to be the celebrity in this family. Look how well Papa George has taught you to play the fiddle! And you can sing, too. You're growing into a beautiful young woman. Some talent scout's going to snap you up."

"Oh Daddy, that's silly. No talent scouts come to the mining towns looking for stars."

"So you'll go to college in New York City or in California," he predicted. "That's my dream. So don't go dumping dirt on top of it, Melody."

I laughed. I was too afraid to have such dreams for myself yet; I was too afraid of being frustrated and trapped like Mommy thought she now was.

I wondered why Daddy didn't feel trapped. No matter how hard things were, he would grin and bear it, and he never joined the other miners to drown his sorrows at the bar. He walked to and from work alone because the other miners lived in the shanties in town.

We lived in Sewell, which was a village born from the mine and built by the mining company in the lap of a small valley. Its main street had a church, a post office, a half dozen stores, two restaurants, a mortuary, and a movie theater open only on the weekends. The shanty homes were all the same pale brown color, built with board-and-batten siding and tar-paper roofs, but at least there were children my age there.

There were no other children near my age living in Mineral Acres trailer park. How I wished I had a brother or a sister to keep me company! When I told Mommy about that wish once, she grimaced and moaned that she was only a child herself when she had me.

"Barely nineteen! And it's not easy to bring children into the world. It's hard on your body and you have to worry about them getting sick and having enough to eat and having proper clothing, not to mention getting them an education. I rushed into motherhood. I should have waited."

"Then I would never have been born!" I complained.

"Of course you would have been born, but you would have been born when things were better and not so hard for us. We were right in the middle of a major change in our lives. It was very difficult."

Sometimes, she sounded as if she blamed me just for being born. It was as if she thought babies just floated around waiting to be conceived, and occasionally they got impatient and encouraged their parents to create them. That's what I had done.

I knew we had moved from Provincetown, Cape Cod, to Sewell in Monongalia County, West Virginia, before I was born, and we didn't have much at the time. Mommy did tell me that when they first arrived in Sewell as poor as they were, she was determined not to live in a shanty, so she and Daddy rented a mobile home in Mineral Acres, even though it was mostly populated by retired people like Papa George.

Papa George wasn't really my grandfather and Mama Arlene wasn't my real grandmother, but they were still like grandparents to me. Mama Arlene had often looked after me when I was a little girl. Papa George had been a coal miner and had retired on disability. He was suffering from black lung, which Daddy said was aggravated by his refusal to give up smoking. His illness made him look much older than his sixty-two years. His shoulders slumped, the lines in his pale, tired face were cut deep, and he was so thin Mama Arlene claimed she could weigh him down with a cable-knit sweater. Still, Papa George and I had the greatest of times when he helped teach me the fiddle.

He complained that it was Mama Arlene's nagging that wore him down. They always seemed to be bickering, but I didn't know any other two people as dedicated to each other as they were. Their arguments were never really mean either. They always ended up laughing.

Daddy loved talking with Papa George. On weekends especially, the two could often be found sitting in the rocking chairs on the cement patio under the metal awning, quietly discussing politics and the mining industry. Papa George was in Sewell during the violent times when the mining unions were being formed and he had lots of stories, which, according to Mama Arlene, were not fit for my ears.

"Why not?" he would protest. "She oughta know the truth about this place and the people who run it."

"She got plenty of time to learn about the ugly things in this world, George O'Neil, without you rushing her into it. Hush up!"

He did, mumbling under his breath until she turned her fiery blue eyes on him, making him swallow the rest of his angry words.

But Daddy agreed with Papa George: the miners were being exploited. This was no life for anyone.

I never understood why Daddy, who was brought up on Cape Cod in a fisherman's family, ended up working in a place where he was shut away from the sun and the sky all day. I knew he missed the ocean, yet we never returned to the Cape and we had nothing to do with Daddy's family. I didn't even know how many cousins I had, or their names, and I had never met or spoken to my grandparents. All I had ever seen was a faded black and white photograph of them with Daddy's father seated and his mother standing beside his father, both looking unhappy about being photographed. His father had a beard and looked as big as Daddy is now. His mother was wispy looking, but with hard, cold eyes.

The family in Provincetown was something Daddy didn't discuss. He would always change the subject, just saying, "We just had differences. It's better we're apart. It's easier this way."

I couldn't imagine why it was easier, but I saw it was painful for him to talk about it. Mommy never wanted to talk about it either. Just bringing up the family caused her to start crying and complaining to me that Daddy's family always thought little of her because she'd been an orphan. She told me she had been adopted by people who she said were too old to raise a child. They were both in their sixties when she was a teenager and they were very strict. She said she couldn't wait to get away from them.

I wanted to know more about them and about Daddy's family, too, but I was afraid it would start an argument between her and Daddy, so after a while, I just stopped asking questions. But that didn't stop their arguments.

One night soon after I had gone to bed, I heard their voices rising against each other. They were in their bedroom, too. The trailer home had a small kitchen to the right of the main entrance, a little dinette and a living room. Down a narrow hallway was the bathroom. My bedroom was the first on the right and Daddy and Mommy's was at the end of the trailer.

"Don't tell me I'm imagining things," Daddy warned, his voice cross. "The people dropping hints ain't liars, Haille," he said. I sat up in bed and listened. It wasn't hard to hear normal conversation through those paperthin trailer walls as it was, but with them yelling at each other, it was as if I were right in the room with them.

"They're not liars. They're busybodies with nothing else to do with their boring, worthless lives than manufacture tales about other people."

"If you don't give them the chance..."

"What am I supposed to do, Chester? The man's the bartender at Frankie's. He talks to everyone, not just me," she whined.

I knew they were arguing about Archie Marlin. I never mentioned it to Daddy, but twice that I knew of, Archie drove Mommy home. Archie had short orange-red hair and skin the shade of milkweed with freckles on his chin and forehead. Everyone said he looked ten years younger than he really was, although no one knew his exact age. No one knew very much about Archie Marlin. He never gave anyone a straight answer to questions about himself. He joked or shrugged and said something silly. Supposedly, he had been brought up in Michigan or Ohio, and had spent six months in jail for forging checks. I never understood why Mommy liked him. She said he was full of good stories and had been to lots of exciting places, like Las Vegas.

She said it again now during the argument in the bedroom.

"At least he's been places. I can learn about them from him," she asserted.

"It's just talk. He hasn't been anywhere," Daddy charged.

"How would you know it's just talk, Chester? You're the one who hasn't been anywhere but the Cape and this trap called Sewell. And you brought me to it!"

"You brought yourself, Haille," he retorted, and suddenly she stopped arguing and started crying. Moments later, he was comforting her so softly I couldn't hear what he was saying and then they grew quiet.

I didn't understand what it all meant. How did Mommy bring herself here? Why would she bring herself to a place she didn't like?

I lay awake, thinking. There were always those deep silences between Mommy and Daddy, gaps they were both afraid to fill. Then the arguments would pass, just as this one did, and it would be as if nothing ever happened, nothing was ever said. It was as if they declared a truce over and over because both knew if they didn't, something terrible might happen, something terrible might be said.

Nothing was as mysterious to me as love between a man and a woman. I had crushes on boys at school and was now sort of seeing Bobby Lockwood more than any other boy. Since my best friend Alice was the smartest girl in school, I thought she might know something about love, even though she had never had a boyfriend. She was nice, but unpopular because she was about twenty-five pounds overweight and her mother made her keep her hair in pigtails. She wasn't allowed to wear any makeup, not even lipstick. Alice read more than anyone I knew, so I thought that maybe she had come across some book that explained love.

She thought a moment after I asked her. She replied it was something scientific. "That's the only way to explain it," she claimed in her usual pedantic manner.

"Don't you think it's something magical?" I asked her. On Wednesday afternoons she would come to our trailer after school and study with me for the weekly Thursday geometry test. It was more for my benefit than hers, for she ended up tutoring me.

"I don't believe in magic," she said dryly. She was not very good at pretending. I was actually her only real friend, maybe partly because she was too brutally honest with her opinions when it came to the other girls at school.

"Well then why is it," I demanded, "that a man will look at one woman specially and a woman will do the same, look at one man specially? Something's got to happen between them, doesn't it?" I insisted.

Alice pressed down on her thick lower lip. Her big, brown round eyes moved from side to side as if she were reading words printed in the air. She had a habit of chewing on the inside of her left cheek, too, when she was deep in thought. The girls in school would giggle and say, "Alice is eating herself again."

"Well," she said after a long pause, "we know we're all made of protoplasm."

"Ugh."

"And chemical things happen between cells," she continued, nodding.

"Stop it."

"So maybe a certain man's protoplasm has a chemical reaction to a certain woman's protoplasm. Something magnetic. It's just positive and negative atoms reacting, but people make it seem like more," she concluded.

"It is more," I insisted. "It has to be! Don't your parents think it's more?"

Alice shrugged. "They never forget each other's birthdays or their anniversary," she said, making it sound as if that was all there was to being in love and married.

Alice's father, William, was Sewell's dentist. Her mother was his receptionist, so they did spend a great deal of time together. But whenever I went to have my teeth checked, I noticed she called her husband Doctor Morgan, as if she weren't his wife, but merely his employee.

Alice had two brothers, both older. Her brother Neal had already graduated and gone off to college and her brother Tommy was a senior and sure to be the class valedictorian.

"Do they ever have arguments?" I asked her. "Bad arguments?" I wondered if it was just something my mommy and daddy did.

"Not terribly bad and very rarely in front of anyone," she said. "Usually, it's about politics."

"Politics?" I couldn't imagine Mommy caring about politics. She always walked away when Daddy and Papa George got into one of their discussions.

"Yes."

"I hope when I get married," I said, "I never have an argument with my husband."

"That's an unrealistic hope. People who live together must have some conflicts. It's natural."

"But if they do, and they're in love, they always make up and feel terrible about hurting each other."

"I suppose," Alice relented. "But that might be just to keep the peace. Once, my parents didn't talk to each other for nearly a week. I think it was when they argued about the last presidential election."

"A week!" I thought for a moment. Even though Mommy and Daddy had their arguments, they always spoke to each other soon afterward and acted as if nothing had happened. "Didn't they kiss each other good night?"

"I don't know. I don't think they do that."

"They don't ever kiss good night?"

Alice shrugged. "Maybe. Of course, they kissed and they must have had sex because my brothers and I were born," she said matter-of-factly.

"Well that means they are in love."

"Why?" Alice asked, her brown eyes narrowing into skeptical slits.

I told her why. "You can't have sex without being in love."

"Sex doesn't have anything to do with love per se," she lectured. "Sexual reproduction is a natural process performed by all living things. It's built into the species."

"Ugh."

"Stop saying ugh after everything I say. You sound like Thelma Cross," she said and then she smiled. "Ask her about sex."

"Why?"

"I was in the bathroom yesterday and overheard her talking to Paula Temple about -- "

"What?"

"You know."

I widened my eyes.

"Who was she with?"

"Tommy Getz. I can't repeat the things she said," Alice added, blushing.

"Sometimes I wonder," I said sitting back on my pillow, "if you and I aren't the only virgins left in our class."

"So? I'm not ashamed of it if it's true."

"I'm not ashamed. I'm just..."

"What?"

"Curious."

"And curiosity killed the cat," Alice warned. She narrowed her round eyes. "How far have you gone with Bobby Lockwood?"

"Not far," I said. She was suddenly staring at me so hard I had to look away.

"Remember Beverly Marks," she warned.

Beverly Marks was infamous, the girl in our eighth-grade class who had gotten pregnant and was sent away. To this day no one knew where she went.

0 "Don't worry about me," I said. "I will not have sex with anyone I don't love."

Alice shrugged skeptically. She was annoying me. I sometimes wondered why I stayed friends with her.

"Let's get back to work." She opened the textbook and ran her forefinger down the page. "Okay, the main part of tomorrow's test will probably be -- "

Suddenly, we both looked up and listened. Car doors were being slammed and someone was crying hard and loudly.

"What's that?" I went to the window in my bedroom. It looked out to the entrance of Mineral Acres. A few of Mommy's co-workers got out of Lois Norton's car. Lois was the manager of the beauty parlor. The rear door was opened and Lois helped Mommy out. Mommy was crying uncontrollably and being supported by two other women as they helped her toward the front door of our trailer. Another car pulled up behind Lois Norton's with two other women in it.

Mommy suddenly let out a piercing scream. My heart raced. I felt my legs turn to stone; my feet seemed nailed to the floor. Mama Arlene and Papa George came out of their trailer to see what was happening. I recognized Martha Supple talking to them. Papa George and Mama Arlene suddenly embraced each other tightly, Mama Arlene's hand going to her mouth. Then Mama Arlene rushed toward Mommy, who was now nearly up to our steps. Tears streamed down my cheeks, mostly from fear.

Alice stood like stone herself, anticipating. "What happened?" she whispered.

I shook my head. I somehow managed to walk out of my room just as the front door opened.

Mommy took a deep breath when she saw me. "Oh Melody," she cried.

"Mommy!" I started to cry. "What's the matter?" I asked through my sobs.

"There's been a terrible accident. Daddy and two other miners...are dead."

A long sigh escaped from Mommy's choked throat. She swayed and would have fallen if Mama Arlene hadn't been holding on to her. However, her eyes went bleak, dark, haunted. Despair had drained her face of its radiance.

I shook my head. It couldn't be true. Yet there was Mommy clutching Mama Arlene, her friends beside and around her, all with horribly tragic faces.

"Nooo!" I screamed and plowed through everyone, down the stairs, outside and away, with my hands over my ears. I was running, unaware of which direction I had taken or that I had left the house without a coat and it was in the middle of one of our coldest Februaries.

I had run all the way to the Monongalia River bend before Alice caught up with me. I was standing there on the hill, embracing myself, gasping and crying at the same time, just gazing dumbly at the beach and the hickory and white oak trees on the other side of the river. A white-tailed deer appeared and gazed curiously at the sound of my sobs.

I shook my head until I felt it might snap off my neck, but I somehow already knew all the No's in the world wouldn't change things. I felt the world horribly altered. I cried until my insides ached. I heard Alice calling and turned to see her gasping for breath as she chugged her way up the hill to where I was standing. She tried to hug and comfort me. I pulled away.

"They're lying," I screamed hysterically. "They're lying. Tell me they're lying."

Alice shook her head. "They said the walls caved in and by the time they got to your father and the others -- "

"Daddy," I moaned. "Poor Daddy."

Alice bit her lower lip and waited for me to stop sobbing. "Aren't you cold?" she asked.

"What difference does it make?" I snapped angrily. "What difference does anything make?"

She nodded. Her eyes were red, too, and she shivered, more from her sadness than the wintry day.

"Let's go back," I said, speaking with the voice of the dead myself.

She walked beside me silently. I don't know how I got my legs to take those steps, but we returned to the trailer park. The women who had brought Mommy home were gone. Alice followed me into the trailer.

Mommy was on the sofa with a wet washcloth on her forehead, and Mama Arlene beside her. Mommy reached up to take my hand and I fell to the floor beside the sofa, my head on her stomach. I thought I was going to heave up everything I had eaten that day. A few moments later, when I looked up, Mommy was asleep. Somewhere deep inside herself she was still crying, I thought, crying and screaming.

"Let me make you a cup of tea," Mama Arlene said quietly. "Your nose is beet red."

I didn't reply. I just sat there on the floor beside the sofa, still holding on to Mommy's hand. Alice stood by the doorway awkwardly.

"I'd better go home," she said, "and tell my parents."

I think I nodded, but I wasn't sure. Everything around me seemed distant. Alice got her books and paused at the doorway.

"I'll come back later," she said. "Okay?"

After she left, I lowered my head and cried softly until I heard Mama Arlene call to me and then touch my arm.

"Come sit with me, child. Let your mother sleep."

I rose and joined her at the table. She poured two cups of tea and sat. "Go on. Drink it."

I blew on the hot water and took a sip.

"When Papa George was down in the mines, I always worried about something like this happening. There were always accidents of one sort or another. We oughta leave that coal alone, find another source of energy,

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...