- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

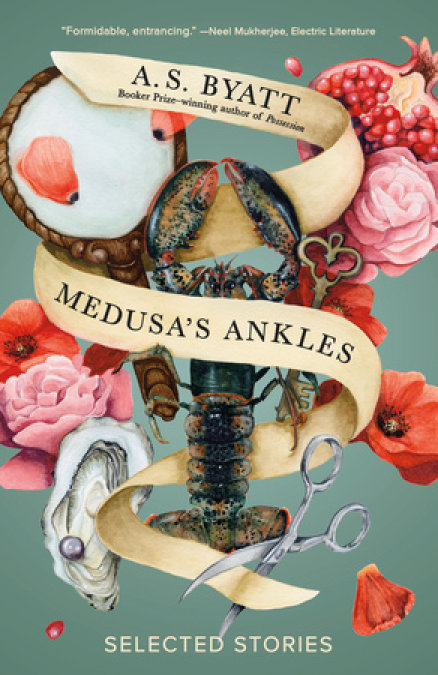

A ravishing, luminous selection of short stories from the prize-winning imagination of A. S. Byatt, "a storyteller who could keep a sultan on the edge of his throne for a thousand and one nights" (The New York Times Book Review). With an introduction by David Mitchell, best-selling author of Cloud Atlas

Mirrors shatter at the hairdresser's when a middle-aged client explodes in rage. Snow dusts the warm body of a princess, honing it into something sharp and frosted. Summer sunshine flickers on the face of a smiling child who may or may not be real.

Medusa's Ankles celebrates the very best of A. S. Byatt's short fiction, carefully selected from a lifetime of writing. Peopled by artists, poets, and fabulous creatures, the stories blaze with creativity and color. From ancient myth to a British candy factory, from a Chinese restaurant to a Mediterranean swimming pool, from a Turkish bazaar to a fairy-tale palace, Byatt transports her readers beyond the veneer of the ordinary—even beyond the gloss of the fantastical—to places rich and strange and wholly unforgettable.

Cover image: © 2021 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Release date: November 23, 2021

Publisher: Vintage

Print pages: 464

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Medusa's Ankles

A.S. Byatt

Sylvia Townsend Warner, and Elizabeth Bowen, and who achieve virtuosity in both short- and long-form fiction. The stories in this volume beguile, illuminate, immerse, unsettle, console, and evoke. They buzz with wit, shimmer with nuance, and misdirect like a street conjuror. They amend, or even rewrite, any putative Rules of the Short Story time and again. They possess a sentient quality. If Medusa’s Ankles was a retrospective exhibition, the gallery would need no guide or “explainer” cards stuck next to the paintings—the stories are perfect and lucid as they stand. For this introduction, however, I’ve settled on three qualities of Byatt’s writing that have a particular glow for me. A brief discussion of these, following a thumbnail biography, are what I’d like to offer the reader, here at the doors of the gallery.

A. S. Byatt was born Susan Drabble in Sheffield in 1936, the eldest daughter of a county court judge and a scholar of Victorian poetry. I hereby succumb to the biographical temptation to locate the sources of thematic streams in Byatt’s fiction in her upbringing: notably, a deep moral engagement; the effect of domineering patriarchs; due reverence for intellect; and a friction between the life of the mind and the life of the housewife. All four Drabble children were educated in Sheffield and York, though the communal confines of boarding school did not suit the bookish future author, and the loneliness of her school years informs one story in this volume, “Racine and the Tablecloth.” Byatt has written approvingly, however, of her Quaker schooling’s respect for silence and listening, and an outsider’s perspective is also a novelist’s perspective. Byatt’s horizons broadened and brightened upon going up to Cambridge to read English in 1954. The emancipations of fifties undergraduate life are fictionalised in her novel Still Life (1978)—as are the casual sexism and taken-as-read elitism. Spells of postgraduate study followed at Bryn Mawr College, Philadelphia, and Somerville College, Oxford. These, too, would be creatively fruitful: few authors engage with the pleasures of scholarship as persuasively as Byatt. Several academics inhabit Medusa’s Ankles, and even if jaded or satirical, they love their work. A. S. Byatt married in 1959 and combined raising a family, lecturing in art, and writing her debut novel, The Shadow of the Sun, published in 1964. She became a full-time writer only in 1983. Despite living in London, her Yorkshire roots assert themselves throughout her oeuvre: Byatt’s literary England has a magnetic north and a cosmopolitan south. Possession won the Booker Prize in 1990 and made A. S. Byatt a household name, in book-reading households at least. The novel remains the author’s best-known work, and ushered in a remarkably industrious decade. In addition to serving on boards for the British Council and the Society of Authors, she travelled widely and wrote Angels and Insects (1992), a diptych of lush, learned novellas; the third novel in the “Frederica Quartet,” Babel Tower (1996); three collections of short stories; and a highly original novel, The Biographer’s Tale (2000). She was made a Dame of the British Empire for services to literature in 1999. The “Frederica Quartet” was concluded with A Whistling Woman in 2002, followed by a fourth story collection, The Little Black Book of Stories (2003), her most recent full-length novel, the Booker-shortlisted The Children’s Book (2009), and a novella of reworked mythology, Ragnarok (2011). Throughout her career, Byatt has written essays, journalism, art criticism, and biography, the latter including books on Iris Murdoch, Wordsworth, and Coleridge, William Morris and the Spanish designer Mariano Fortuny. Her life of scholarship, literature, art, and ideas informs, and is reflected in, the stories in these pages. All writers turn their lives and selves into writing: it’s the “how” and the “what” of this act of alchemy that is unique to each writer; and it is to a trio of qualities of A. S. Byatt’s particular alchemy to which I now turn.

Firstly, note the sheer range. Most great short-story writers are distinctive stylists more than they are stylistic chameleons. Most habitual readers of short stories could pass a “Name That Author” test and identify, say, Raymond Carver, Anton Chekhov, or Alice Munro by a single page of their prose. As a rule of thumb, however, the more readily identifiable the author, the narrower the world of the author’s literary corpus. Narrowness of world does not equate with narrowness of vision, or mind, or skill. Infinity can indeed be held in the palm of a hand, and eternity in an hour. A. S. Byatt’s stories bypass this rule of thumb with relish. She is both a highly distinctive stylist—ornate, cerebral, “Byatty”—and a short-story writer whose menu of answers to the question “What form can a story take?” is long, varied, and rich. “The July Ghost” is a portrait of a mother who has lost a child and an agnostic ghost story. It is subtle, poignant, and ever so slightly trippy. In contrast, “Sugar” is a meandering clamber around a family tree, ripe with memorable anecdote and northern-hued. “Precipice-Encurled” is a set of framed narratives about the poet Robert Browning, a family he knew in Italy, a young artist and a woman who models for him. It is sumptuous, expectation-busting, heartbreaking, and immune to classification. “Racine and the Tablecloth” is a tale of a vulnerable pupil and her ambiguously predatory schoolmistress set in an all-girls’ boarding school. This may be Muriel Spark turf, but Byatt’s story reads like biography and feels shot in black and white.

So much for the first four stories of Medusa’s Ankles: my point is, I could describe the next fourteen in the collection, and none would much resemble the others. When I encounter this degree of writerly omnivorousness, I speculate about its source. Kipling’s formidable range came from a peripatetic life spent in (and between) different worlds; and from, to use a now-quaint word, his adventures. I wonder if Byatt’s range comes from inner conversations with what she reads; from a scholar’s delight in exploring the rabbit warrens of research; and from a likeable openness to genre fiction. It was traditional for literary figures of Byatt’s generation and altitude on the literary ladder to distinguish between serious literary fiction and genre fiction, and to allot respect, study, and awards only to the former. As I write in the early 2020s, this distinction is fading—Bob Dylan has won the Nobel Prize in Literature and Booker longlists may now include graphic novels—but genre snobbery is still alive, well, and writing reviews. (I have the bruises to prove it.) A. S. Byatt is the opposite of a genre snob. In this collection, “Dragons’ Breath”uses, well, dragons, in the service of a fever-dream parable. “Cold” is a fairy story with a feminist twist. “Dolls’ Eyes” flirts with Gothic horror, and is steeped in the genre’s history cleverly enough to outwit the reader. “A Stone Woman” melds fantasy, psychology, Ovid, and Scandinavian myth to delineate both the metamorphosis of a widow into a crystal she-troll and the stages of grief. “The Lucid Dreamer,” a tale of an experimental psychonaut entering free fall, occupies that zone of British science fiction staked out by J. G. Ballard and John Wyndham. I’m not claiming that Byatt is a genre writer, or that Medusa’s Ankles should be exiled to the SF/Fantasy section (shudder!). The full spectrum of the English literary canon, in all its realist glory, is present and correct too—George Eliot, Henry James, Proust, Virginia Woolf, D. H. Lawrence, Iris Murdoch. As a literary traveller, however, Byatt engages with writers as far off the Leavisite road map as the Brothers Grimm, Italo Calvino, Ursula le Guin, Neil Gaiman. (During a conversation with Gaiman I told him how much A. S. Byatt enjoyed his fantasy novel Coraline. He replied without hesitation, “Antonia’s one of us.”) Byatt’s scholarly knowledge of English literature, combined with her freethinking attitude to genre, produces magnificent hybrids. The longest story here, “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye,” is built of distinct modes of writing that are rarely found in the same room. We begin with middle-class kitchen-sink drama: Gillian Perholt, the protagonist, has been dumped by her husband for a younger woman. The story segues into literary theory when Gillian, a narratologist, presents a paper at a conference in Ankara. Next up is travel writing, as Gillian visits museums and mosques. Then, stunningly, this near-novella veers into fantasy, when a djinn is freed by Gillian from an old bottle acquired in a bazaar. Surreal comedy—no spoilers, but watch out for a cameo by tennis player Boris Becker—is followed by a wholly persuasive interspecies romance. The story’s breathtaking genre shifts make “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye” utterly unpredictable, and its themes dynamic and various. It is Byatt at her magpie-minded, ideas-studded, plot-driven best.

To an art historian, angels, dragons, and dreamscapes are as legitimate subjects as sunflowers, haystacks, and realist portraits. A. S. Byatt’s scholarly knowledge of art informs her prose as pervasively as (Doctor) Chekhov’s knowledge of medicine and human malaises informs his. Certainly, Byatt’s characters are introduced with a portraitist’s eye. Of Ines’s mother in “A Stone Woman” we are told, “[She]—a strong bright woman—had liked to live amongst shades of mole and dove.” Some of Byatt’s most vivid creations are painters, like Joshua Riddell, the artist in “Precipice-Encurled”; or art lecturers, like Professor Perry Diss (“Bury this?”) in “The Chinese Lobster” who falls foul of campus politics; or artists in the broader senses, like Hew the architect in “The Narrow Jet,” Thorsteinn the sculptor from “A Stone Woman,” or the oneiric artist in “The Lucid Dreamer.” Such characters are Byatt’s conduits for ideas about making art, looking at art and art’s centrality to the mind and the world. “Precipice-Encurled” features John Ruskin—from whom art lecturers claim professional descent—and Joshua Riddell, engaging with Ruskin’s idea’s before our very eyes:

Monsieur Monet had found a solution to the problem posed by Ruskin, of how to paint light, with the small range of colours available: he had trapped light in his surface, light itself was his subject. His paint was light. He had painted, not the thing seen, but the act of seeing.

This conversation happens across years and ontological boundaries. Few writers embed theory in their fiction with Byatt’s boldness and success. The theories of art are sometimes illustrated by the very story that houses them. The line quoted above—“He had painted, not the thing seen, but the act of seeing”—is embedded in “Precipice-Encurled” as much by characters’ perceptions of what happens, as by what actually happens. Art powered by the dissonance between characters’ interiors and the world’s exteriority is as old as Shakespeare and Cervantes, but Byatt elevates this dissonance itself to subject and theme. And plot and structure, when occasion permits. “Ekphrasis”—the use of a work of visual art as a literary device—is a word seldom reached for in everyday conversation, but it’s a perfect fit for “Christ in the House of Martha and Mary.” The story imagines the circumstances around the titular painting by Diego Velázquez—a picture that encloses a picture—from the viewpoint of Concepción, the cook who appears in the Velázquez painting. This story is unfussy about those oft-mystified concepts “inspiration” and “the creative process.” It bestows dignity upon art in all its manifestations, including cooking. Byatt’s Velázquez addresses Concepción not as a disposable domestic but as a respected equal:

The cook, as much as the painter, looks into the essence of the creation not, as I do, in light and on surfaces, but with all the other senses, with taste, and smell, and touch, which God also made in us for purposes ... the world is full of light and life, and the true crime is not to be interested in it. You have a way in. Take it. It may incidentally be a way out, as all skills are.

Byatt can describe a painter at work with the vivacity and precision of a skilled football pundit. I would call these passages “notoriously difficult” to write, but the phrase feels misleading—so few writers even try. In this sensuous passage from “Precipice-Encurled,” artist Joshua Riddell sketches Juliana Fishwick, daughter in the family with whom he is staying in Italy. It is a double love scene between Joshua and Juliana, and between artist and vocation:

His pencil point hovered, thinking, and Juliana’s pupils contracted in the greenish halo of the iris, as she looked into the light, and blinked, involuntarily. She did not want to stare at him; it was unnatural, though his considering gaze, measuring, drawing back, turning to one side and the other, seemed natural enough. A flood of colour moved darkly up her throat, along her chin, into the planes and complexities of her cheeks.

If Velázquez is an established artist and Joshua Riddell a wunderkind, Bernard Lycett-Kean in “A Lamia in the Cévennes”is an artist-in-progress. The story is comic—a lamia gets trapped in an English expat’s swimming pool—and cerebral, as we watch Bernard fall in love not with the mythological seductress, but with art itself. The story is a kind of serio-comedic miniature of Van Gogh’s collected letters to his brother Theo—a self-drawn road map of artistic growth. In this passage, Bernard notices that reality represents itself as shifting fields of colours and luminosities, mirrored by Byatt in her prose:

The best days were under racing cloud, when the aquamarine took on a cool grey tone, which was then chased back, or rolled away, by the flickering gold-in-blue of yellow light in liquid. In front of his prow or chin in the brightest lights moved a mesh of hexagonal threads, flashing rainbow colours, flashing liquid silver-gilt, with a hint of molten glass; on such days liquid fire, rosy and yellow and clear, rain across the dolphin, who lent it a thread of intense blue.

It is not easy to think of another writer with so painterly and exact an eye for the colours, textures, and appearances of things. The visual is in constant dialogue with the textual. One aftereffect of reading Byatt resembles the aftereffect of a morning in an art gallery whereby, upon leaving, I find myself framing rectangles in my field of vision and looking at them—at the world—as I might a painting. These stories are in constant dialogue with readers, asking, “What is art?” and “Why do we need it?” and “What does it do to us?” and “Why make the damn stuff?” These questions linger long after putting the book down. This thought-bubble of Bernard’s could feasibly puff out of the skull of any writer, or artist of any bent:

He muttered to himself. Why bother. Why does this matter so much. What difference does it make to anything if I solve this blue and just start again. I could just sit down and drink wine. I could go and be useful in a cholera camp in Colombia or Ethiopia. Why bother to render the transparency in solid paint on a bit of board. I could just stop.

He could not.

Art is a mercurial lover. One artist you’ll meet in these pages pays a truly shocking final price for his devotion to his art. Yet art is also what saves Bernard from the titular lamia. For Velázquez, art is the key that unlocks life. Whatever chord the stories end on, the artists can no more ignore their art than a character can change the story they appear in, or a Greek hero outwit the Fates.

Metafiction, my dictionary tells me, is “fiction in which the author self-consciously alludes to the artificiality or literariness of a work by parodying or departing from novelistic conventions and traditional narrative techniques.” Quite a mouthful, and not an overly appetising one. Metafiction as practised during 1980s “peak-postmodernism” led up some sterile cul-de-sacs. How can a reader care about a character who discusses his own fictionality? Metafiction in A. S. Byatt’s stories is subtler, however, often wrapped up with voice, and is an urbane pleasure of her work. First-person narratives are the “home viewpoint” for many a fine writer, but they require an extra act of complicity from the reader, who must “believe” not only the story but also in the reality of its fictional narrator. Byatt’s stories are all third-person, told by a narrator who balances the needs of the story—keep that disbelief suspended, keep the reader caring—with the “insider information” that only a sentient narrator can impart. On occasion, the narrator is chatty, pondering aloud at the start of “Racine and the Tablecloth,” “When was it clear that Martha Crichton-Walker was the antagonist?” Since we, the readers of said story, can’t be expected to know the answer, the narrator elaborates: “Emily found this word for her much later, when she was a grown woman.” Sometimes the narrator alludes to the reader’s role in fiction by inviting us to fill in an onerous blank, as in the story of Gillian Perholt’s dumping, by fax, by her husband. “It was long and self-exculpatory, but there is no need for me to recount it to you, you can very well imagine it for yourself.” From time to time the narrator will philosophise, noting that if the newly-wed Fiammarosa (from “Cold”) was sometimes lonely in her glass palace, “this was not unusual, for no one has everything they can desire.” Such remarks bridge Fiammarosa’s fantastical reality with our own less fantastical one, and make the point that the workings of the heart—and marriage—are pretty much the same, whether they reside in an enchanted palace or a house with a postcode. Elsewhere, the narrator offers cinematic “fore-flashes”: in one of the frame narratives in “Precipice-Encurled,” a woman is waiting for the poet Robert Browning. “She ... will do this for many years,” prophesies the authorial voice, thereby elongating this character’s sad arc, and shading her in tones of Miss Havisham and The Aspern Papers. The effect reminds me of watching a film with a taciturn director’s commentary; or, more precisely, a film whose script includes a few remarks spoken by the director from behind the camera. Narrators clued up on the act of narration are, of course, nothing new. Chaucer was at it in the 1300s—but there’s a self-knowing quality to Byatt’s narrator’s self-knowledge that renders the mechanisms of these stories sporadically visible. At these moments I even sense Byatt observing the reader through her narrator, like Dutch painters painting their own reflections in mirrors.

As “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye” is metafictional by way of being a Narratologist’s Tale, so the story “Raw Material”is fiction about fiction. Jack Smollett (the names of Byatt’s characters hum with allusion) is a one-hit-wonder, ex–Angry Young Man novelist who, in the 1960s, “left for London and fame, and returned quietly, ten years later.” Jack lives off a circle of students who are unencumbered by a surfeit of talent. One week, the octogenarian Cicely Fox appears in his class with a brief essay, “How We Used to Black-Lead Stoves.” The essay itself is included in “Raw Material,” as are a couple of follow-ups. Jack sees the merit and authenticity in Cicely’s work as “the real thing.” Artistically, the semi-washed-up youngish writer is smitten and reignited by the senior. The essays, the narrator tells us, “made Jack want to write. They made him see the world as something to be written.” If the “painter” stories allow Byatt to depict a painter painting, “Raw Material” enables Byatt to write a writer discussing writing. Byatt ricochets ideas between these metafictional levels. “He had given up telling them that Creative Writing was not a form of psychotherapy. In ways both sublime and ridiculous it clearly was, precisely, that.” Tonally, “sublime and ridiculous” would be a fair description of the whole story. It is about the clarity offered by poetry and prose; about why writers write what writers write about. It is dark, shocking, and exhibits Byatt’s ticklish sense of the ridiculous. It is a counterpoint to death, which arrives with all the warning an owl gives a vole. The narrative eye of “Sea Story” has the godlike precision of a GPSsatellite, tracking the voyage of a message in a bottle from Filey to its (un-Romantic) destination in the Great Caribbean Trash Vortex. Meditatively, brilliantly, the story gives form to Byatt’s recurring theme of epistemology: What are the limits of knowledge? What do we know is true, and what do we merely believe is true? Is truth a constant, or a lover’s words on a page of paper rolled up in a plastic Perrier bottle doomed to split open, disintegrate, and end up inside a mollyhawk’s chicks?

About 170 pages from this one you’ll meet Orhan Rifat, a cosmopolitan Turkish academic, waiting for Gillian Perholt at Ankara airport. Orhan will refer to a statue’s breasts, explaining: “They are metaphors. They are many things at once, as the sphinxes and winged bulls are many things at once.” These remarkable stories, too, are many things at once. Chains of cause and effect. Puzzle boxes. Meditations. Learned discourses. Statements of regret and offerings of solace. X-rays of the heart. Showcases of beauty for beauty’s own sake. Views of a world where, to be sure, bad things can happen to good people; but also where happy-ish endings, qualified by realism, are not beyond hope. Step inside. Take your time. Savour your discoveries. “They sat in silence and were amazed, briefly and forever.”

—David Mitchell

May 2021

THE JULY GHOST

“I think I must move out of where I’m living,” he said. “I have this problem with my landlady.”

He picked a long, bright hair off the back of her dress, so deftly that the act seemed simply considerate. He had been skilful at balancing glass, plate, and cutlery, too. He had a look of dignified misery, like a dejected hawk. She was interested.

“What sort of problem? Amatory, financial, or domestic?”

“None of those, really. Well, not financial.”

He turned the hair on his finger, examining it intently, not meeting her eye.

“Not financial. Can you tell me? I might know somewhere you could stay. I know a lot of people.”

“You would.” He smiled shyly. “It’s not an easy problem to describe. There’s just the two of us. I occupy the attics. Mostly.”

He came to a stop. He was obviously reserved and secretive. But he was telling her something. This is usually attractive.

“Mostly?” Encouraging him.

“Oh, it’s not like that. Well, not ... Shall we sit down?”

They moved across the party, which was a big party, on a hot day. He stopped and found a bottle and filled her glass. He had not needed to ask what she was drinking. They sat side by side on a sofa: he admired the brilliant poppies bold on her emerald dress, and her pretty sandals. She had come to London for the summer to work in the British Museum. She could really have managed with microfilm in Tucson for what little manuscript research was needed, but there was a dragging love affair to end. There is an age at which, however desperately happy one is in stolen moments, days, or weekends with one’s married professor, one either prises him loose or cuts and runs. She had had a stab at both, and now considered she had successfully cut and run. So it was nice to be immediately appreciated. Problems are capable of solution. She said as much to him, turning her soft face to his ravaged one, swinging the long bright hair. It had begun a year ago, he told her in a rush, at another party actually; he had met this woman, the landlady in question, and had made, not immediately, a kind of faux pas, he now saw, and she had been very decent, all things considered, and so ...

He had said, “I think I must move out of where I’m living.” He had been quite wild, had nearly not come to the party, but could not go on drinking alone. The woman had considered him coolly and asked, “Why?” One could not, he said, go on in a place where one had once been blissfully happy, and was now miserable, however convenient the place. Convenient, that was, for work, and friends, and things that seemed, as he mentioned them, ashy and insubstantial compared to the memory and the hope of opening the door and finding Anne outside it, laughing and breathless, waiting to be told what he had read, or thought, or eaten, or felt that day. Someone I loved left, he told the woman. Reticent on that occasion too, he bit back the flurry of sentences about the total unexpectedness of it, the arriving back and finding only an envelope on a clean table, and spaces in the bookshelves, the record stack, the kitchen cupboard. It must have been planned for weeks, she must have been thinking it out while he rolled on her, while she poured wine for him, while ... No, no. Vituperation is undignified and in this case what he felt was lower and worse than rage: just pure, childlike loss. “One ought not to mind places,” he said to the woman. “But one does,” she had said. “I know.”

She had suggested to him that he could come and be her lodger, then; she had, she said, a lot of spare space going to waste, and her husband wasn’t there much. “We’ve not had a lot to say to each other, lately.” He could be quite self-contained, there was a kitchen and a bathroom in the attics; she wouldn’t bother him. There was a large garden. It was possibly this that decided him: it was very hot, central London, the time of year when a man feels he would give anything to live in a room opening onto grass and trees, not a high flat in a dusty street. And if Anne came back, the door would be locked and mortice-locked. He could stop thinking about Anne coming back. That was a decisive move: Anne thought he wasn’t decisive. He would live without Anne.

For some weeks after he moved in he had seen very little of the woman. They met on the stairs, and once she came up, on a hot Sunday, to tell him he must feel free to use the garden. He had offered to do some weeding and mowing and she had accepted. That was the weekend her husband came back, driving furiously up to the front door, running in, and calling in the empty hall, “Imogen, Imogen!” To which she had replied, uncharacteristically, by screaming hysterically. There was nothing in her husband, Noel’s, appearance to warrant this reaction; their lodger, peering over the banister at the sound, had seen their upturned faces in the stairwell and watched hers settle into its usual prim and placid expression as he did so. Seeing Noel, a balding, fluffy-templed, stooping thirty-five or so, shabby corduroy suit, cotton polo neck, he realised he was now able to guess her age, as he had not been. She was a very neat woman, faded blond, her hair in a knot on the back of her head, her legs long and slender, her eyes downcast. Mild was not quite the right word for her, though. She explained then that she had screamed because Noel had come home unexpectedly and startled her: she was sorry. It seemed a reasonable explanation. The extraordinary vehemence of the screaming was probably an echo in the stairwell. Noel seemed wholly downcast by it, all the same.

He had kept out of the way, that weekend, taking the stairs two at a time and lightly, feeling a little aggrieved, looking out of his kitchen window into the lovely, overgrown garden, that they were lurking indoors, wasting all the summer sun. At Sunday lunchtime he had heard the husband, Noel, shouting on the stairs.

“I can’t go on, if you go on like that. I’ve done my best, I’ve tried to get through. Nothing will shift you, will it, you won’t try,will you, you just go on and on. Well, I have my life to live, you can’t throw a life away ... can you?”

He had crept out again onto the dark upper landing and seen her standing, halfway down the stairs, quite still, watching Noel wave his arms and roar, or almost roar, with a look of impassive patience, as though this nuisance must pass off. Noel swallowed and gasped; he turned his face up to her and said plaintively,

“You do see I can’t stand it? I’ll be in touch, shall I? You must want ... you must need ... you must ...”

She didn’t speak.

“If you need anything, you know where to get me.”

“Yes.”

“Oh, well ...” said Noel, and went to the door. She watched him, from the stairs, until it was shut, and then came up again, step by step, as though it was an effort, a little, and went on coming, past her bedroom, to his landing, to come in and ask him, entirely naturally, please to use the garden if he wanted to, and please not to mind marital rows. She was sure he understood ... things were difficult ... Noel wouldn’t be back for some time. He was a journalist: his work took him away a lot. Just as well. She committed herself to that “just as well.” She was a very economical speaker.

So he took to sitting in the garden. It was a lovely place: a huge, hidden, walled south London garden, with old fruit trees at the end, a wildly waving disorderly buddleia, curving beds full of old roses, and a lawn of overgrown, dense ryegrass. Over the wall at the foot was the Common, with a footpath running behind all the gardens. She came out to the shed and helped him to assemble and oil the lawn mower, standing on the little path under the apple branches while he cut an experimental serpentine across her hay. Over the wall came the high sound of children’s voices, and the thunk and thud of a football. He asked her how to raise the blades: he was not mechanically minded.

“The children get quite noisy,” she said. “And dogs. I hope they don’t bother you. There aren’t many safe places for children, round here.”

He replied truthfully that he never heard sounds that didn’t concern him, when he was concentrating. When he’d got the lawn into shape, he was going to sit on it and do a lot of reading, try to get his mind in trim again, to write a paper on Hardy’s poems, on their curiously archaic vocabulary.

“It isn’t very far to the road on the other side, really,” she said. “It just seems to be. The Common is an illusion of space, really. Just a spur of brambles and gorse bushes and bits of football pitch between two fast four-laned main roads. I hate London commons.”

“There’s a lovely smell, though, from the gorse and the wet grass. It’s a pleasant illusion.”

“No illusions are pleasant,” she said, decisively, and went in. He wondered what she did with her time: apart from little shopping expeditions she seemed to be always in the house. He was sure that when he’d met her she’d been introduced as having some profession: vaguely literary, vaguely academic, like everyone he knew. Perhaps she wrote poetry in her north-facing living room. He had no idea what it would be like. Women generally wrote emotional poetry, much nicer than men, as Kingsley Amis has stated, but she seemed, despite her placid stillness, too spare and too fierce—grim?—for that. He remembered the screaming. Perhaps she wrote Plath-like chants of violence. He didn’t think that quite fitted the bill, either. Perhaps she was a freelance radio journalist. He didn’t bother to ask anyone who might be a common acquaintance. During the whole year, he explained to the American at the party, he hadn’t actually discussed her with anyone. Of course he wouldn’t, she agreed vaguely and warmly. She knew he wouldn’t. He didn’t see why he shouldn’t, in fact, but went on, for the time, with his narrative.

They had got to know each other a little better over the next few weeks, at least on the level of borrowing tea, or even sharing pots of it. The weather had got hotter. He had found an old-fashioned deck chair, with faded striped canvas, in the shed, and had brushed it over and brought it out on to his mown lawn, where he sat writing a little, reading a little, getting up and pulling up a tuft of couch grass. He had been wrong about the children not bothering him: there was a succession of incursions by all sizes of children looking for all sizes of balls, which bounced to his feet, or crashed in the shrubs, or vanished in the herbaceous border, black and white footballs, beach balls with concentric circles of primary colours, acid-yellow tennis balls. The children came over the wall: black faces, brown faces, floppy long hair, shaven heads, respectable dotted sun hats and camouflaged cotton army hats from Milletts. They came over easily, as though they were used to it, sandals, training shoes, a few bare toes, grubby sunburned legs, cotton skirts, jeans, football shorts. Sometimes, perched on the top, they saw him and gestured at the balls; one or two asked permission. Sometimes he threw a ball back, but was apt to knock down a few knobby little unripe apples or pears. There was a gate in the wall, under the fringing trees, which he once tried to open, spending time on rusty bolts only to discover that the lock was new and secure, and the key not in it.

The boy sitting in the tree did not seem to be looking for a ball. He was in a fork of the tree nearest the gate, swinging his legs, doing something to a knot in a frayed end of rope that was attached to the branch he sat on. He wore blue jeans and training shoes, and a brilliant tee shirt, striped in the colours of the spectrum, arranged in the right order, which the man on the grass found visually pleasing. He had rather long blond hair, falling over his eyes, so that his face was obscured.

“Hey, you. Do you think you ought to be up there? It might not be safe.”

The boy looked up, grinned, and vanished monkey-like over the wall. He had a nice, frank grin, friendly, not cheeky.

He was there again, the next day, leaning back in the crook of the tree, arms crossed. He had on the same shirt and jeans. The man watched him, expecting him to move again, but he sat, immobile, smiling down pleasantly, and then staring up at the sky. The man read a little, looked up, saw him still there, and said,

“Have you lost anything?”

The child did not reply: after a moment he climbed down a little, swung along the branch hand over hand, dropped to the ground, raised an arm in salute, and was up over the usual route over the wall.

Two days later he was lying on his stomach on the edge of the lawn, out of the shade, this time in a white tee shirt with a pattern of blue ships and water-lines on it, his bare feet and legs stretched in the sun. He was chewing a grass stem, and studying the earth, as though watching for insects. The man said, “Hi, there,” and the boy looked up, met his look with intensely blue eyes under long lashes, smiled with the same complete warmth and openness, and returned his look to the earth.

He felt reluctant to inform on the boy, who seemed so harmless and considerate: but when he met him walking out of the kitchen door, spoke to him, and got no answer but the gentle smile before the boy ran off towards the wall, he wondered if he should speak to his landlady. So he asked her, did she mind the children coming in the garden. She said no, children must look for balls, that was part of being children. He persisted—they sat there, too, and he had met one coming out of the house. He hadn’t seemed to be doing any harm, the boy, but you couldn’t tell. He thought she should know.

He was probably a friend of her son’s, she said. She looked at him kindly and explained. Her son had run off the Common with some other children, two years ago, in the summer, in July, and had been killed on the road. More or less instantly, she had added drily, as though calculating that just enough information would preclude the need for further questions. He said he was sorry, very sorry, feeling to blame, which was ridiculous, and a little injured, because he had not known about her son, and might inadvertently have made a fool of himself with some casual reference whose ignorance would be embarrassing.

What was the boy like, she said. The one in the house? “I don’t—talk to his friends. I find it painful. It could be Timmy, or Martin. They might have lost something, or want ...”

He described the boy. Blond, about ten at a guess, he was not very good at children’s ages, very blue eyes, slightly built, with a rainbow-striped tee shirt and blue jeans, mostly though not always—oh, and those football practice shoes, black and green. And the other tee shirt, with the ships and wavy lines. And an extraordinarily nice smile. A really warm smile. A nice-looking boy.

He was used to her being silent. But this silence went on and on and on. She was just staring into the garden. After a time, she said, in her precise conversational tone,

“The only thing I want, the only thing I want at all in this world, is to see that boy.”

She stared at the garden and he stared with her, until the grass began to dance with empty light, and the edges of the shrubbery wavered. For a brief moment he shared the strain of not seeing the boy. Then she gave a little sigh, sat down, neatly as always, and passed out at his feet.

After this she became, for her, voluble. He didn’t move her after she fainted, but sat patiently by her, until she stirred and sat up; then he fetched her some water, and would have gone away, but she talked.

“I’m too rational to see ghosts, I’m not someone who would see anything there was to see, I don’t believe in an afterlife, I don’t see how anyone can, I always found a kind of satisfaction for myself in the idea that one just came to an end, to a sliced-off stop. But that was myself; I didn’t think he—not he—I thought ghosts were—what people wanted to see, or were afraid to see ... and after he died, the best hope I had, it sounds silly, was that I would go mad enough so that instead of waiting every day for him to come home from school and rattle the letter box I might actually have the illusion of seeing or hearing him come in. Because I can’t stop my body and mind waiting, every day, every day, I can’t let go. And his bedroom, sometimes at night I go in, I think I might just for a moment forget he wasn’t in there sleeping, I think I would pay almost anything—anything at all—for a moment of seeing him like I used to. In his pyjamas, with his—his—his hair ... ruffled, and, his ... you said, his ... that smile.

“When it happened, they got Noel, and Noel came in and shouted my name, like he did the other day, that’s why I screamed, because it—seemed the same—and then they said, he is dead, and I thought coolly, is dead, that will go on and on and on till the end of time, it’s a continuous present tense, one thinks the most ridiculous things, there I was thinking about grammar, the verb to be, when it ends to be dead ... And then I came out into the garden, and I half saw, in my mind’s eye, a kind of ghost of his face, just the eyes and hair, coming towards me—like every day waiting for him to come home, the way you think of your son, with such pleasure, when he’s—not there—and I—I thought—no, I won’t see him, because he is dead, and I won’t dream about him because he is dead, I’ll be rational and practical and continue to live because one must, and there was Noel ...

“I got it wrong, you see, I was so sensible, and then I was so shocked because I couldn’t get to want anything—I couldn’t talk to Noel—I—I—made Noel take away, destroy, all the photos, I—didn’t dream, you can will not to dream, I didn’t ... visit a grave, flowers, there isn’t any point. I was so sensible. Only my body wouldn’t stop waiting and all it wants is to—to see that boy. That boy. That boy you—saw.”

He did not say that he might have seen another boy, maybe even a boy who had been given the tee shirts and jeans afterwards. He did not say, though the idea crossed his mind, that maybe what he had seen was some kind of impression from her terrible desire to see a boy where nothing was. The boy had had nothing terrible, no aura of pain about him: he had been, his memory insisted, such a pleasant, courteous, self-contained boy, with his own purposes. And in fact the woman herself almost immediately raised the possibility that what he had seen was what she desired to see, a kind of mix-up of radio waves, like when you overheard police messages on the radio, or got BBC One on a switch that said ITV. She was thinking fast, and went on almost immediately to say that perhaps his sense of loss, his loss of Anne, which was what had led her to feel she could bear his presence in her house, was what had brought them—dare she say—near enough, for their wavelengths to mingle, perhaps, had made him susceptible ... You mean, he had said, we are a kind of emotional vacuum, between us, that must be filled. Something like that, she had said, and had added, “But I don’t believe in ghosts.”

Anne, he thought, could not be a ghost, because she was elsewhere, with someone else, doing for someone else those little things she had done so gaily for him, tasty little suppers, bits of research, a sudden vase of unusual flowers, a new bold shirt, unlike his own cautious taste, but suiting him, suiting him. In a sense, Anne was worse lost because voluntarily absent, an absence that could not be loved because love was at an end, for Anne.

“I don’t suppose you will, now,” the woman was saying. “I think talking would probably stop any—mixing of messages, if that’s what it is, don’t you? But—if—if he comes again”—and here for the first time her eyes were full of tears—“if—you must promise, you will tell me, you must promise.”

He had promised, easily enough, because he was fairly sure she was right, the boy would not be seen again. But the next day he was on the lawn, nearer than ever, sitting on the grass beside the deck chair, his arms clasping his bent, warm brown knees, the thick, pale hair glittering in the sun. He was wearing a football shirt, this time, Chelsea’s colours. Sitting down in the deck chair, the man could have put out a hand and touched him, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...