- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

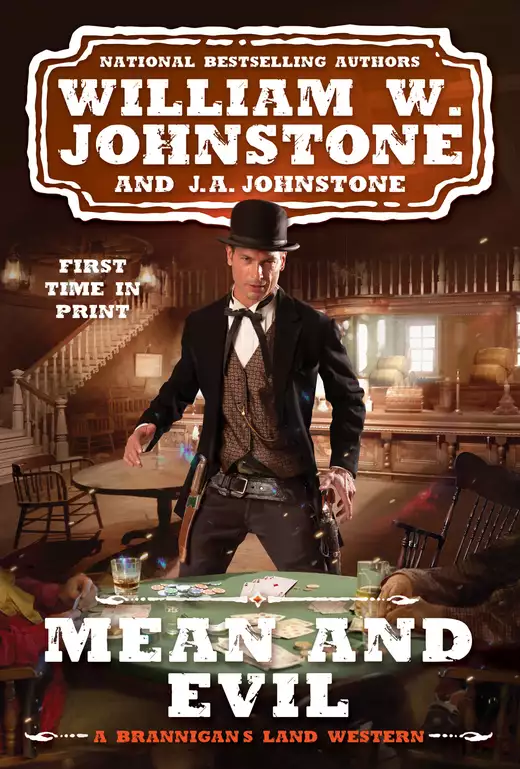

The national bestselling western authors William W. Johnstone and J.A. Johnstone bring us another Ty Brannigan western with a unique and American brand of justice.

JOHNSTONE COUNTRY. WHERE FAMILY COMES FIRST.

Ex-lawman turned cattle rancher Ty Brannigan loves his wife and children. And may Lord have mercy on those who would harm them—because Ty Brannigan will show none.

KILLER SMILE

No one knows their way around a faro table, bank vault, or six shooter more than Smilin’ Doc Ford. When he’s not gambling or thieving, he’s throwing lead—or, if he’s feeling especially vicious, slitting throats with his Arkansas toothpick. Roaming the west with Doc is a band of wild outlaws including a pair of hate-filled ex-cons and the voluptuous Zenobia “Zee” Swallow, Doc’s kill-crazy lady.

The gang have been on a killing spree, leaving a trail of bodies near Ty Brannigan’s Powderhorn spread in Wyoming’s Bear Paw Mountains. U.S. marshals want Ty to help them track down Smilin’ Doc’s bunch. But when the hunt puts the Brannigan clan in the outlaws’ sights, Ty and his kin take justice into their own hands—and deliver it with a furious, final vengeance.

Live Free. Read Hard.

Release date: September 27, 2022

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Mean and Evil

William W. Johnstone

“It ain’t dark over here by the fire,” countered Dad’s younger cow-punching partner, Pete Driscoll.

“No, but it sure is dark out here.” Dad—a short, bandy-legged, gray-bearded man in a bullet-crowned cream Stetson that had seen far better days a good twenty years ago—stood at the edge of the firelight, holding back a pine branch as he surveyed the night-cloaked, Bear Paw Mountain rangeland beyond him.

“If you’ve become afraid of the dark in your old age, Dad, why don’t you come on over here by the fire, take a load off, and pour a cup of coffee? I made a fresh pot. Thick as day-old cow plop, just like you like it. I’ll even pour some of my who-hit-John in it if you promise to stop caterwaulin’ like you’re about to be set upon by wolves.”

Dad stood silently scowling off into the star-capped distance. Turning his head a little to one side, he asked quietly in a raspy voice, “Did you hear that?”

“Hear what?”

“That.” Dad turned his head a little more to one side. “There it was again.”

Driscoll—a tall, lean man in his mid-thirties and with a thick, dark-red mustache mantling his upper lip—stared across the steaming tin cup he held in both hands before him, pricking his ears, listening. A sharpened matchstick drooped from one corner of his mouth. “I didn’t hear a thing.”

Dad turned his craggy, bearded face toward the younger man, frowning. “You didn’t?”

“Not a dadgum thing, Dad.” Driscoll glowered at his partner from beneath the broad brim of his black Stetson.

He’d been paired with Clawson for over five years, since they’d both started working at the Stevens’ Kitchen Sink Ranch on Owlhoot Creek. In that time, they’d become as close as some old married couples, which meant they fought as much as some old married couples.

“What’s gotten into you? I’ve never known you to be afraid of the dark before.”

“I don’t know.” Dad gave his head a quick shake. “Somethin’s got my blood up.”

“What is it?”

Dad glowered over his shoulder at Driscoll. “If I knew that, my blood wouldn’t be up—now, would it?”

Driscoll blew ripples on his coffee and sipped. “I think you got old-timer’s disease. That’s what I think.” He sipped again, swallowed. “Hearin’ things out in the dark, gettin’ your drawers in a twist.”

Dad stood listening, staring out into the night. The stars shone brightly, guttering like candles in distant windows in small houses across the arching vault of the firmament. Finally, he released the pine bough; it danced back into place. He turned and, scowling and shaking his head, ambled back over to the fire. His spurs chinged softly. On a flat, pale rock near the dancing orange flames, his speckled tin coffeepot, which owned the dent of a bullet fired long ago by some cow-thieving Comanche bushwhacker in the Texas Panhandle, gurgled and steamed.

“Somethin’s out there—I’m tellin’ ya. Someone or something is movin’ around out there.” Dad grabbed his old Spencer repeating rifle from where it leaned against a tree then walked back around the fire to stand about six feet away from it, gazing out through the pines and into the night, holding the Spencer down low across his skinny thighs clad in ancient denims and brush-scarred, bull-hide chaps.

Driscoll glanced over his shoulder at where his and Dad’s hobbled horses contentedly cropped grass several yards back in the pines. “Horses ain’t nervy.”

Dad eased his ancient, leathery frame onto a pine log, still keeping his gaze away from the fire, not wanting to compromise his night vision. “Yeah, well, this old coot is savvier than any broomtail cayuse. Been out on the range longer than both of them and you put together, workin’ spreads from Old Mexico to Calvary in Alberta.” He shook his head slowly. “Coldest damn country I ever visited. Still got frost bite on my tired old behind from the two winters I spent up there workin’ for an ornery old widder.”

“Maybe you got frostbite on the brain, too, Dad.” Driscoll grinned.

“Sure, sure. Make fun. That’s the problem with you, Pete. You got no respect for your elders.”

“Ah, hell, Dad. Lighten up.” Driscoll set his cup down and rummaged around in his saddlebags. “Come on over here an’ let’s plays us some two-handed—” He cut himself off abruptly, sitting up, gazing out into the night, his eyes wider than they’d been two seconds ago.

Dad shot a cockeyed grin over his shoulder. “See?”

“What was that?”

Dad cast his gaze through the pines again, to the right of where he’d been gazing before. “Hard to say.”

“Hoot owl?”

“I don’t think so.”

The sound came again—very quiet but distinct in the night so quiet that Dad thought he could hear the crackling flames of the stars.

“Ah, sure,” Driscoll said. “A hoot owl. That’s all it was!” He chuckled. “Your nerves is right catching, Dad. You’re infecting my peaceable mind. Come on, now. Get your raggedy old behind over here and—” Again, a sound cut him off.

Driscoll gave an involuntary gasp then felt the rush of blood in his cheeks as they warmed with embarrassment. The sound was unlike anything Dad or Pete Driscoll had ever heard before. A screeching wail? Sort of catlike. But it hadn’t been a cat. At least, like no cat Dad had ever heard before, and he’d heard a few during his allotment. Night-hunting cats could sound pure loco and fill a man’s loins with dread. But this had been no cat.

An owl, possibly. But, no. It hadn’t been an owl, either.

Dad’s old heart thumped against his breastbone.

It thumped harder when a laugh vaulted out of the darkness. He swung his head sharply to the left, trying to peer through the branches of two tall Ponderosa pines over whose lime-green needles the dull, yellow, watery light of the fire shimmered.

“That was a woman,” Driscoll said quietly, his voice low with a building fear.

The laugh came again. Very quietly. But loudly enough for Dad to make out a woman’s laugh, all right. Sort of like the laugh of a frolicking employee in some house of ill repute in Cheyenne or Laramie, say. The laugh of a prostitute mildly drunk and engaged in a game of slap ‘n’ tickle with some drunken, frisky miner or track layer who’d paid downstairs and was swiping at the woman’s bodice with one hand while holding a bottle by the neck with his other hand.

Dad rose from his log. Driscoll rose from where he’d been leaning back against his saddle, reached for his saddle ring Winchester, and slowly, quietly levered a round into the action. He followed Dad over to the north edge of the camp.

Dad pushed through the pine branches, holding his own rifle in one hand, his heart still thumping heavily against his breastbone. His tongue was dry, and he felt a knot in his throat. That was fear.

He was not a fearful man. Leastways, he’d never considered himself a fearful man. But that was fear, all right. Fear like he’d known it only once before and that was when he’d been alone in Montana, tending a small herd for an English rancher, and a grizzly had been prowling around in the darkness beyond his fire, occasionally edging close enough so that the flames glowed in the beast’s eyes and reflected off its long, white, razor-edged teeth it had shown Dad as though a promise of imminent death and destruction.

The cows had been wailing fearfully, scattering themselves up and down the whole damn valley . . .

But the bear had seemed more intent on Dad himself.

That was a rare kind of fear. He’d never wanted to feel it again. But he felt it now, all right. Sure enough.

He stepped out away from the trees and cast his gaze down a long, gentle, sage-stippled slope and beyond a narrow creek that glistened like a snake’s skin in the starlight. He jerked with a start when he heard a spur trill very softly behind him and glanced to his right to see Driscoll step up beside him, a good half a foot taller than the stoop-shouldered Dad.

Driscoll gave a dry chuckle, but Dad knew Pete was as unnerved as he was.

Both men stood in silence, listening, staring straight off down the slope and across the water, toward where they’d heard the woman laugh.

Then it came again, louder. Only, this time it came from Dad’s left, beyond a bend in the stream.

Dad’s heart pumped harder. He squeezed his rifle in both sweating hands, bringing it up higher and slipping his right finger through the trigger guard, lightly caressing the trigger. The woman’s deep, throaty, hearty laugh echoed then faded. Then the echoes faded, as well.

“What the hell’s goin’ on?” Driscoll said. “I don’t see no campfire over that way.”

“Yeah, well, there’s no campfire straight out away from us, neither, and that’s where she was two minutes ago.”

Driscoll clucked his tongue in agreement.

The men could hear the faint sucking sounds of the stream down the slope to the north, fifty yards away. That was the only sound. No breeze. No birds. Not even the rustling, scratching sounds little animals made as they burrowed.

Not even the soft thump of a pinecone falling out of a tree.

It was as though the entire night was collectively holding its breath, anticipating something bad about to occur.

The silence was shattered by a loud yowling wail issuing from behind Dad and Driscoll. It was a yapping, coyote-like yodeling, only it wasn’t made by no coyote. No, no, no. Dad heard the voice of a man in that din. He heard the mocking laughter of a man in the cacophony as he and Driscoll turned quickly to stare back toward their fire and beyond it, their gazes cast with terror.

The crazy, mocking yodeling had come from the west, the opposite direction from the woman’s first laugh.

Dad felt a shiver in Driscoll’s right arm as it pressed up against Dad’s left one.

“Lord almighty,” his partner said. “They got us surrounded. Whoever they are!”

“Toyin’ with us,” Dad said, grimacing angrily.

Then the woman’s voice came again, issuing from its original direction, straight off down the slope and across the darkly glinting stream. Both men grunted their exasperation as they whipped around again and stared off toward the east.

“Sure as hell, they’re toyin’ with us!” Driscoll said tightly, angrily, his chest expanding and contracting as he breathed. “What the hell do they want?” He didn’t wait for Dad’s response. He stepped forward and, holding his cocked Winchester up high across his chest, shouted, “What the hell do you want?”

“Come on out an’ show yourselves!” Dad bellowed in a raspy voice brittle with terror.

Driscoll gave him a dubious look. “Sure we want ’em to do that?”

Dad only shrugged and continued turning his head this way and that, heart pounding as he looked for signs of movement in the deep, dark night around him.

“Hey, amigos,” a man’s deep, toneless voice said off Dad and Driscoll’s left flanks. “Over here!”

Both men whipped around with more startled grunts, extending their rifles out before them, aiming into the darkness right of their fire, looking for a target but not seeing one.

“That one’s close!” Driscoll said. “Damn close!”

Now the horses were stirring in the brush and trees beyond the fire, not far from where that cold, hollow voice had issued. They whickered and stumbled around, whipping their tails against their sides.

“That tears it!” Pete said. He moved forward, bulling through the pine boughs, angling toward the right of his and Dad’s fire which had burned down considerably, offering only a dull, flickering, red radiance.

“Hold on, Pete!” Dad said. “Hold on!”

But then Pete was gone, leaving only the pine boughs jostling behind him.

“Where are you, dammit?” Pete yelled, his own voice echoing. “Where the hell are you? Why don’t you come out an’ show yourselves?”

Dad shoved his left hand out, bending a pine branch back away from him. He stepped forward, seeing the fire flickering straight ahead of him, fifteen feet away. He quartered to the right of the fire, not wanting its dull light to outline him, to make him a target. He could hear Pete’s spurs ringing, his boots thudding and crackling in the pine needles ahead of him, near where the horses were whickering and prancing nervously.

“What the hell do you want?” Pete cried, his voice brittle with exasperation and fear. “Why don’t you show yourselves, darn it?” His boot thuds dwindled in volume as he moved farther away from the fire, spurs ringing more softly.

Dad jerked violently when Pete’s voice came again: “There you are! Stop or I’ll shoot, damn you!”

A rifle barked once, twice, three times.

“Stop—” Pete’s voice was drowned by another rifle blast, this one issuing from farther away than Pete’s had issued. And off to Dad’s left.

Straight out from Dad came an anguished cry.

“Pete!” Dad said, taking one quaking footstep forward, his heart hiccupping in his chest. “Pete! ”

Pete cried out again. Running, stumbling footsteps sounded from the direction Pete had gone. Dad aimed the rifle, gazing in terror toward the sound of the footsteps growing louder and louder. A man-shaped silhouette grew before Dad, and then, just before he was about to squeeze the Spencer’s trigger, the last rays of the dying fire played across Pete’s sweaty face.

He was running hatless and without his rifle, his hands clamped over his belly.

“Pete!” Dad cried again, lowering the rifle.

“Dad!” Pete stopped and dropped to his knees before him. He looked up at the older man, his hair hanging in his eyes, his eyes creased with pain. “They’re comin’, Dad!” Then he sagged onto his left shoulder and lay groaning and writhing.

“Pete!” Dad cried, staring down in horror at his partner.

His friend’s name hadn’t entirely cleared his lips before something hot punched into his right side. The punch was followed by the wicked, ripping report of a rifle. He saw the flash in the darkness out before him and to the right.

Dad wailed and stumbled sideways, giving his back to the direction the bullet had come from. Another bullet plowed into his back, just beneath his right shoulder, punching him forward. He fell and rolled, wailing and writhing.

He rolled onto his back, the pain of both bullets torturing him.

He spied movement in the darkness to his right.

He spied more movement all around him.

Grimacing with the agony of what the bullets had done to him, he pushed up onto his elbows. Straight out away from him, a dapper gent in a three-piece, butternut suit and bowler hat stepped up from the shadows and stood before him. He looked like a man you’d see on a city street, maybe wielding a fancy walking stick, or at a gambling layout in San Francisco or Kansas City. The dimming firelight glinted off what appeared a gold spike in his rear earlobe.

The man stared down at Dad, grinning. He was strangely handsome, clean-shaven, square-jawed. At first glance, his smiling eyes seemed warm and intelligent. He appeared the kind of man you’d want your daughter to marry.

Dad looked to his left and blinked his eyes, certain he wasn’t seeing who he thought he saw—a beautiful flaxen-haired woman with long, impish blue eyes dressed all in black including a long, black duster. The duster was open to reveal that she wore only a black leather vest and a skirt under it. The vest highlighted more than concealed the heavy swells of her bosoms trussed up behind the tight-fitting, form-accentuating vest.

The woman smiled down at Dad, tipped her head back, and gave a catlike laugh.

If cats laughed, that was.

There was more movement to Dad’s right. He turned in that direction to see a giant of a man step up out of the shadows.

A giant of a full-blooded Indian. Dressed all in buckskins and with a red bandanna tied around the top of his head, beneath his low-crowned, straw sombrero. Long, black hair hung down past his shoulders, and two big pistols jutted on his hips. He held a Yellowboy repeating rifle in both his big, red hands across his waist. He stared dully through flat, coal-black eyes down at Dad.

Dad gasped with a start when he heard crunching footsteps behind him, as well. He turned his head to peer over his shoulder at another big man, this one a white man.

He stepped out of the shadows, holding a Winchester carbine down low by his side. He was nearly as thick as he was tall, and he had a big, ruddy, fleshy face with a thick, brown beard. His hair was as long as the Indian’s. On his head was a badly battered, ancient Stetson with a crown pancaked down on his head, the edges of the brim tattered in places. He grunted down at Dad then, working a wad of chaw around in his mouth, turned his head and spat to one side.

Dad turned back to the handsome man standing before him.

As he did, the handsome man, lowered his head, reached up, and pulled something out from behind his neck. He held it out to show Dad.

A pearl-handled Arkansas toothpick with a six-inch, razor-edged blade.

To go along with his hammering heart, a cold stone dropped in Dad’s belly.

The man smiled, his eyes darkening, the warmth and intelligence Dad had previously seen in them becoming a lie, turning dark and seedy and savage. He turned and walked over to where Pete lay writhing and groaning.

“No,” Dad wheezed. “Don’t you do it, you devil!”

The handsome man dropped to a knee beside Pete. He grabbed a handful of Pete’s hair and jerked Pete’s head back, exposing Pete’s neck.

Pete screamed.

The handsome man swept the knife quickly across Pete’s throat then stepped back suddenly to avoid the blood geysering out of the severed artery.

Pete choked and gurgled and flopped his arms and kicked his legs as he died.

The handsome man turned to Dad.

“Oh, God,” Dad said. “Oh, God.”

So this was how it was going to end. Right here. Tonight. Cut by a devil who looked like a man you’d want your daughter to marry. Aside from the eyes, that was . . .

As though reading Pete’s mind, the handsome man grinned down at him. He shuttled that demon’s smile to the others around him and then stepped forward and crouched down in front of Dad.

The last thing Dad felt before the dark wing of death closed over him was a terrible fire in his throat.

“You think those rustlers are around here, Pa?” Matt Brannigan asked his father.

Just then, Tynan Brannigan drew his coyote dun to a sudden stop, and curveted the mount, sniffing the wind. “I just now do, yes.”

“Why’s that?” Matt asked, frowning.

Facing into the wind, which was from the southwest, Ty worked his broad nose beneath the brim of his high-crowned tan Stetson. “Smell that?”

“I don’t smell nothin’.”

“Face the wind, son,” Ty said.

He was a big man in buckskins, at fifty-seven still lean and fit and broad through the shoulders, slender in the hips, long in the legs. His tan face with high cheekbones and a strawberry blond mustache to match the color of his wavy hair which hung down over the collar of his buckskin shirt, was craggily handsome. The eyes drawn up at the corners were expressive, rarely veiling the emotions swirling about in his hot Irish heart; they smiled often and owned the deeply etched lines extending out from their corners to prove it.

Ty wasn’t smiling now, however. Earlier in the day, he and Matt had cut the sign of twelve missing beeves as well as the horse tracks of the men herding them. Of the long-looping devils herding them, rather. Rustling was no laughing matter.

Matt, who favored his father though at nineteen was not as tall and was much narrower of bone, held his crisp cream Stetson down on his head as he turned to sniff the wind, which was blowing the ends of his knotted green neckerchief as well as the glossy black mane of his blue roan gelding. He cut a sidelong look at his father and grinned. “Ah.”

“Yeah,” Ty said, jerking his chin up to indicate the narrow canyon opening before him in the heart of west-central Wyoming Territory’s Bear Paw Mountains. “That way. They’re up Three Maidens Gulch, probably fixin’ to spend the night in that old trapper’s cabin. The place has a corral so they’d have an easy time keeping an eye on their stolen beef.”

“On our beef,” Matt corrected his father.

“Good point.” Ty put the spurs to the dun and galloped off the trail they’d been on and onto the canyon trail, the canyon’s stony walls closing around him and Matt galloping just behind his father. The land was rocky so they’d lost the rustler’s sign intermittently though it was hard to entirely lose the sign of twelve beeves on the hoof and four horseback riders.

A quarter mile into the canyon, the walls drew back and a stream curved into the canyon from a secondary canyon to the east. Glistening in the high-country sunlight and sheathed in aspens turning yellow in the mountain fall, their wind-jostled leaves winking like newly minted pennies, the stream hugged the trail as it dropped and turned hard and flinty then grassy as it bisected a broad meadow then became hidden from Ty and Matt’s view by heavier pines on their right.

The forest formed the shape of an arrow as it cut down from the stream toward Ty and Matt. That arrow point crossed the trail a hundred yards ahead of them as they followed the trail through the forest fragrant with pine duff and moldering leaves.

At the edge of the trees, Ty drew the dun to a halt. Matt followed suit, the spirited roan stomping and blowing.

Ty gazed ahead at a rocky saddle rising before them a hundred yards away. Rocks and pines and stunted aspens stippled the rise and rose to the saddle’s crest.

“The cabin’s on the other side of that rise,” he said, reaching forward with his right hand and sliding his Henry repeating rifle from its saddle sheath.

Both gun and sheath owned the marks of time and hard use. Ty had used the Henry during his town taming years in Kansas and Oklahoma, and the trusty sixteen-shot repeater had held him in good stead. So had the stag-butted Colt .44 snugged down in a black leather holster thonged on his buckskin-clad right thigh.

The thong was the mark of a man who used his hogleg often and in a hurry, but that was no longer true. Ty had been ranching and raising his family in these mountains for the past twenty years, ever since he’d met and married his four children’s lovely Mexican mother, the former Beatriz Salazar, sixteen years Ty’s junior.

He no longer used his weapons anywhere near as much as when he’d been the town marshal of Hayes or Abilene, Kansas or Guthrie, Oklahoma. Only at such times as now, when rustlers were trying to winnow his herd, or when old enemies came gunning for him, which had happened more times than he wanted to think about. At such times he always worried first and foremost for the safety of his family.

His family’s welfare was paramount.

That’s what he wanted to talk to Matt about now . . .

He turned to his son, who had just then slid his own Winchester carbine from its saddle sheath and rested it across his thighs. “Son,” Ty said, “there’s four of ’em.”

“I know, Pa.” Matt levered a round into his Winchester’s action then off-cocked the hammer. He grinned. “We can take ’em.”

“If this were a year ago, I’d send you home.”

Again, Matt grinned. “You’d try.”

Ty laughed in spite of the gravity of the situation he found himself in—tracking four long-loopers with a son he loved more than life itself and wanted no harm to come to. “You and your sister,” Ty said, ironically shaking his head. He was referring to his lovely, headstrong daughter, MacKenna, who at seventeen was two years younger than Matt but in some ways far more worldly in the ways seventeen-year-old young women can be and more worldly than boys and even men.

Especially those who were Irish mixed with Latina.

Mack, as MacKenna was known by those closest to her, was as good with a horse and a Winchester repeating rifle as Matt was, and Matt knew it. Sometimes Ty thought she was as good with the shooting irons as he himself was. Part of him almost wished she were here.

“You’re nineteen now,” Ty told Matt.

“Goin’ on twenty,” Matt quickly added.

“Out here, that makes a man.” Ty jerked his head to indicate the saddle ahead of them. “They have a dozen of our cows, and they can’t get away with them. They have to be taught they can’t mess with Powderhorn beef. If we don’t teach ’em that, if they get away with it—”

“I know, Pa. More will come. Like wolves on the blood scent.”

“You got it.” Ty narrowed one grave eye at his son. “I want you to be careful. Take no chances. If it comes to shootin’, and we’d best assume it will because those men likely know what the penalty for rustling is out here, remember to breathe and line up your sights and don’t hurry your shots or you’ll pull ’em. But fo. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...