- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

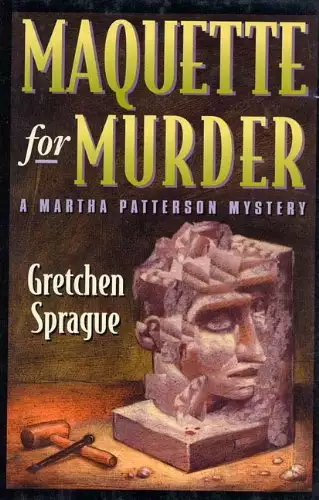

When retired attorney Martha Patterson's sculptor friend, Hannah Gold, is attacked, her assistant battered to death, and her latest sculpture destroyed, Martha plunges into the New York art world to find the culprit while threading her way through the jealousies and loyalties of a group of people for whom "the unusual is just usual."

Release date: February 12, 2000

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 240

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Maquette for Murder

Gretchen Sprague

The taxi stopped in front of a steel overhead door, halfway down a block of steel overhead doors. What distinguished this particular door from its neighbors were the brick-faced second story above it, the horizontal strip of security-wired windows, pale with interior light, cut into it, and the accumulation of cars parked along the curb in front of it. The cab had to stop in the middle of the street, but no honks or epithets resulted; at six-thirty in the evening, the trucks that frequented the working warehouses had retired for the day.

"This is it?" asked Joe Gianni.

"This is it," said Martha Patterson. Hannah Gold's studio, Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

Martha allowed Joe to pay their fare, accepted his offered hand, and with no more than a token protest from her aging knees, emerged into the showery, but not at the moment showering, May evening. A many-voiced babble drifted out to the street through an open, human-sized door to the left of the overhead door. The invitation had said 5-8, but they were not really late; as everyone knows, the stated hours for a stand-up reception amount to little more than a suggestion.

Inside, clots of people, wineglasses in hand and voices at New York volume, stood among a scattering of Hannah's works that were displayed around the room. While Joe wrestled their raincoats onto the rented coatrack, Martha watched Hannah excuse herself from one of the groups and bustle across to them. Her soft gray garment—certainly silk, for no other substance would flow so liquidly, and certainly designed and produced by Hannah herself, for fabric was her medium—fluttered with the breeze of her passage. The color matched her hair, the neck-to-ankle drapery camouflaged her grandmotherly figure, and the cut of the costume proclaimed her an artist as surely as Martha's tailored dress and Joe's suit and tie defined them as professionals.

Crying, "At last, at last," Hannah enfolded Martha in her arms, then released her and held out both hands to Joe. "And Mr. Gianni, of course. Lovely of you to come." Four months past her sixty-third birthday, she was as excited as a girl celebrating her sweet sixteen.

Martha, who had known Joe professionally for upwards of three decades, was accustomed to thinking of him as restrained beyond the average. But any New Yorker who has achieved a degree of worldly success has mastered cocktail party etiquette; Joe took Hannah's offered hands and air-kissed in the direction of her cheek. "Joe, please," he said. "It's very kind of you to have me."

"Oh, Joe, please, I'm the soul of kindness." The skin around her eyes crinkling, Hannah released his hands and linked arms with him and Martha. "Come, eat and make nice over the baby."

"The . . ." That did perplex Joe for a moment.

"The maquette," Martha cued him.

Earlier, when she'd granted his rather surprising request to accompany her to this reception, she had found it necessary to explain that a maquette was a small-scale model of a proposed large work of art. This one, whose display was the occasion for the party, represented the most recent stage of Hannah's autumn-blooming career: it was her entry in a competition for a large-scale sculptural work to be installed in a corporate space in Minneapolis.

"The maquette, of course," said Joe. "I'm looking forward to it."

The gray-painted concrete floor had been swept clean of the ravelings of thread and odd little fabric scraps that accumulated when Hannah was working, the industrial sewing machines at the side of the room were covered, and the caterer had disguised the big table on which Hannah cut out her patterns with a leaf-green cloth. They sampled properly runny Brie and trendily high-fiber crackers; then, carrying plastic glasses of better-than-tolerable wine, they began a meandering journey across the room, interrupted every few steps by introductions: two or three dealers; a writer from a slick-paper art magazine; a tall, fortyish man with a ponytail of gray-flecked mahogany-colored hair, who was talking with great intensity about the interplay of light and shadow to three women, two of them very young and very attentive, the third a stocky woman with Asian features whose smile said she'd heard it all before but didn't mind hearing it again.

The maquette, illuminated by a pair of spotlights on a ceiling track, stood on a blocky waist-high pedestal a few feet out from the far side wall. A bulky man in worn jeans and scuffed work boots was standing in front of it, his arms folded across his chest. Serious biceps bulged his T-shirt, and the overhead light created an aureole around his shaved brown scalp. It wasn't until he turned that Martha recognized him as a sculptor who, at his last opening, had been wearing an Al Sharpton haircut.

"Love," he said. He appeared to be addressing Joe.

Joe raised his eyebrows and sipped his wine.

"Joe Gianni, this is Dennison Simm," said Hannah. "Martha, I know you've met Dennie."

Martha nodded. Joe shifted his wineglass to his left hand, extended his right hand, and said, "How do you do."

Simm grasped the offered hand in a complex grip that might have had some street significance. "Do?" he boomed. "About like everybody else, I guess. Eat, drink, fuck, work. How about you, man?" It wasn't clear that he expected an answer; as he spoke, his gaze slid away across the room.

Nevertheless, Joe responded. His right hand still imprisoned, he produced a cocktail-party smile and said, "Well, I suppose that about sums it up."

The answer reclaimed Simm's attention. "Good man," he barked. He released Joe's right hand and slapped his left shoulder. Joe managed to extend his arm far enough to let the jostled wine miss his trousers and splat onto the floor.

"Love?" This time Simm was addressing Hannah. "Like gettin' married?" His voice slid up the scale into an Amos-and-Andy parody. "Maybe one a them tents they put up for a weddin' down on the ol' plantation? Keep the sun off all the massas an' missuses scarfin' up the mint juleps 'longside the magnolias?" But again his attention wandered across the room.

This time Martha let her gaze follow his. He seemed to be watching a young woman who was standing near the back wall, partly concealed by an abstract metal sculpture on a chest-high pedestal. Dredging the depths of her unreliable memory for names, Martha came up, first with Olive, and then with Quist. Olive Quist, who would be Olive Simm if she had chosen to take her husband's name.

Was Dennison Simm watching his wife or assessing the art?

Martha's judgment declared the woman to be the more worthy of attention. Her skin was the color of milky cocoa; her hair was teased into a dark froth around her head; her body, inside a red minidress, was nubile; her legs below the abbreviated skirt were shapely.

Obviously unaware of her husband's scrutiny, she was gazing into the middle distance. Once more Martha let another person's concentration direct her own gaze. While Dennison Simm was watching Olive, Olive seemed to be watching the ponytailed man who had been discoursing on light and dark, his three female listeners, and a second man, younger and slimmer, who had joined them. With lowered eyelids and curved lips, this newcomer was directing a stereotypically seductive gaze, not at either of the young women, one of whom was smiling in his direction, but at the Asian woman, who was ignoring him.

"Well." Simm returned his attention to Hannah. "Guess it's 'bout time to be gettin' on. Thanks for the invite, Miz Gold, ma'am." Once more he cuffed Joe, who this time avoided spillage altogether, and said, "Good to meet you, man."

When he had passed beyond earshot, Joe said, "Odd man."

"A good sculptor, though." Hannah spoke absently; most of her attention, like Martha's, was following Dennison Simm, who was heading for his wife. "Oh, child!" she breathed, "be careful!"

Olive had reached blindly toward the sculpture beside her and, still staring at the group in the middle of the room, was stroking a smooth area near its base. She was obviously unaware of Simm's approach until he was only a step away. He clamped his fingers around her wrist and jerked her hand away. The sudden motion rocked the sculpture on its pedestal. Almost absentmindedly, Simm steadied it with his free hand while with his other hand he twisted Olive's wrist at an angle that had to be painful.

Joe started forward half a step.

"Let it be," said Hannah.

Joe glanced at her and subsided.

And almost at once, the domestic drama turned anticlimactic. Simm transferred his grip from his wife's wrist to her upper arm; to anyone who had missed what had gone before, the grasp might appear as affectionate. Thus linked, they made their way toward the coatrack by the door.

The next act, if any, would take place elsewhere. Martha retrieved her attention and directed it to the maquette.

She had seen almost nothing of this work's progress, though she had heard much. Like many of Hannah's recent pieces, it was an arrangement of patterned fabric draped over a framework. What was new was its over-the-top lavishness. The maquette was much scaled down, of course; it measured about four feet high, three feet wide, and a couple of feet deep. The installed work was to be twelve feet high. The drapery would consist of hundreds of yards of hand-stenciled parachute fabric, whose folds would form passages leading viewers into a center chamber. There, a white linen cloth encrusted with embroidery would be draped over a lopsided structure resembling a misshapen altar. On this structure, securely fastened against pilferage, would rest a tattered stuffed object that vaguely resembled an emaciated teddy bear.

This creature, the altar cloth, and a scale model of the altar were displayed beside the maquette. A set of computer renderings that showed what a walk through the work would be like was mounted on the wall behind it, next to a blueprint of the armature, which was to be constructed of riveted and welded I-beams.

"Hi, Hannah, I'm sorry to be so late," said a voice behind them. "Hi, Martha." Wendy Kahane, Hannah's assistant until a few weeks ago, had arrived.

Wendy was somewhere between youth and middle age, thick-waisted and double-chinned, with a rebellious tangle of dark hair. Martha liked her a great deal.

"Oh, there you are!" Hannah said. Embraces were exchanged; Joe was introduced.

"So what do you think of Love?" Wendy demanded.

"Love?" said Joe.

"Love is its name," said Hannah.

"Oh. Yes. I see." Joe sipped his wine. "So if somebody wants to call it a wedding marquee . . ."

"Dennie is not stupid," said Hannah.

"Matter of opinion," said Wendy. Something behind them seemed to catch her eye; she said, "Oh, God," and began to sidle off. "I'll talk to you later, Hannah."

Martha turned. A young man—the one who had joined the group to which Olive Quist's attention had been directed—had left that group and was approaching.

"Don't run away," Hannah called after Wendy. "We're going to dinner."

Wendy looked back over her shoulder, glanced once more at the newcomer, and raised her eyebrows.

The snub was obvious, but the young man's smile did not waver, although his eyelids flickered for an instant.

Hannah reasserted control. "Martha, Joe," she said, "this is my new assistant, Kent Reed. Kent, my dearest friend, Martha Patterson, and her friend Joe Gianni."

So this was Kent Reed. Martha had heard a good deal about this beautiful young man (Hannah's epithet) who was Wendy's replacement, but this was their first meeting. She offered her hand and said, "How do you do." Beautiful was not an exaggeration; he was tall, loose-limbed, and high-cheekboned; his skin was a shade between cafe au lait and pale beige; he wore his hair in a neat modified Afro.

"Martha, what a treat," he murmured. He didn't exactly shake her offered hand; he gave it a squeeze that was probably meant to flatter with a hint of affection. Perversely, Martha was simply annoyed. He said, "I've heard so much . . ."

"And," Hannah repeated, "her friend Joe Gianni."

Instantly obedient, he released Martha's hand and modulated his manner from charm to good fellow. "Mr. Gianni," he said. "Joe. How are you?"

Sepia. That was the word for the beautiful young man's skin color.

Joe's right hand had found its way into his coat pocket. He left it there, nodded, cleared his throat, and said, "Fine. And you?"

Kent nodded at the maquette. "Isn't it marvelous?"

Joe cleared his throat once more and said, "Impressive."

And there the conversation stalled; no one seemed to have anything more to say. As speechlessness engulfed them, Hannah stood with her hands folded loosely in front of her, a thoughtful line etched between her brows. She might have been conceiving a new work to be called Awkwardness.

And all at once an imp sprang forward from the lawless recesses of Martha's mind. "You must be an artist, Kent," she said.

"Ah, well," he said. "I aspire."

Ah, well? Good heavens. Martha looked across the room at the upright piece Olive Quist had been caressing. "A sculptor, perhaps?" prodded the imp.

The sepia skin flushed. "Well, I've made a few pieces," Kent said, "but lately I've been getting into the artistic potential of digital imaging."

Martha's interest in computer-generated art was less than minimal. She ignored this lead and said, "Might that metal piece over there be one of yours? I don't think I've seen it before."

The flush deepened. "Yes," Kent said. "Yes, that's mine."

"Interesting," Martha said. "Would you mind if I had a look?"

"What a question," said Hannah.

The piece was an abstraction, about three feet high: a slender curving upright column of steel, its ascent interrupted in three places by rough-cast lumps five or six inches across. Kent had not come over with them, which was fortunate; Martha would have been hard put to formulate a comment acceptable to the artist. Generally receptive to abstract sculpture, she thought the piece should have interested her more than it did, but some failure of proportion left her unmoved. Perhaps the artist had already experienced such a reaction and had no stomach for another.

"Not?" said Hannah.

"The performance doesn't seem to come up to the concept," Martha said.

"Oh well, it never does. The physical object corrupts the purity of the concept." With that amused crinkling of the skin around her eyes, Hannah added, "That's critic-ese. In English, it means that stuff doesn't care what you want it to do. Stuff has ideas of its own. Sometimes they're better, sometimes they're worse."

"That's all very well," Martha said, "but the problem with this piece isn't the stuff, it's the eye. There's something wrong with the proportions."

"Oh, you." Hannah looked at Joe. "What do you think?"

But Joe shook his head. "I'm afraid I'm no judge. I'm new at this."

"That doesn't matter. One way or another, everybody responds." Hannah closed one hand around the slender area that Olive Quist had caressed. It was as obvious a handhold as the neck of a baseball bat. Supporting the top with her other hand, she lifted the sculpture from the base and offered it to him. "Here," she said, "forget looking at it. Sculpture is tactile. Feel it."

Joe hesitated.

"Don't be afraid of responding," Hannah said. "Let your hands feel the steeliness of it. Let your muscles support the mass."

"Won't it corrode?" Joe said. "From acids in the skin, things like that?"

"And what if it does? It's stuff. If corroding is its nature, it will corrode. Paint fades, stone crumbles, metal corrodes. Look at us; we wither and die. Have you seen the old stone saints with the toes worn away by the kisses of the faithful? That's their nature." She thrust the metal shaft toward him. "Don't be afraid."

Adversaries more experienced than Joe had been hard put to resist Hannah. He set his empty wineglass on the corner of the pedestal and took the sculpture from her, holding it as she had: his left hand gripping the slender area at the base, his right hand supporting the top. He hefted it for a moment and handed it back. "Yes, I see what you mean," he said. Martha did not detect much conviction in his voice.

Hannah thrust it toward Martha. "Your eyes don't like it. What do your muscles say?"

No more able to resist than Joe, and far more willing to go along, Martha took it. The thing was heavy, but the balance wasn't too bad. And it was a good thing that its maker had avoided coming with them, for the imp, still running the show, transported Martha five decades back in time. She moved her right hand down to grip the smooth handhold just above her left hand, planted her feet, poised the thing just above her right shoulder, leaned forward at the waist, and mimed a batter awaiting the pitcher's delivery.

"Oh, you're bad." But Hannah didn't try to hide her grin. She took Kent Reed's piece out of Martha's hands and set it back on its pedestal.

1 Love

The taxi stopped in front of a steel overhead door, halfway down a block of steel overhead doors. What distinguished this particular door from its neighbors were the brick-faced second story above it, the horizontal strip of security-wired windows, pale with interior light, cut into it, and the accumulation of cars parked along the curb in front of it. The cab had to stop in the middle of the street, but no honks or epithets resulted; at six-thirty in the evening, the trucks that frequented the working warehouses had retired for the day.

"This is it?" asked Joe Gianni.

"This is it," said Martha Patterson. Hannah Gold's studio, Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

Martha allowed Joe to pay their fare, accepted his offered hand, and with no more than a token protest from her aging knees, emerged into the showery, but not at the moment showering, May evening. A many-voiced babble drifted out to the street through an open, human-sized door to the left of the overhead door. The invitation had said 5-8, but they were not really late; as everyone knows, the stated hours for a stand-up reception amount to little more than a suggestion.

Inside, clots of people, wineglasses in hand and voices at New York volume, stood among a scattering of Hannah's works that were displayed around the room. While Joe wrestled their raincoats onto the rented coatrack, Martha watched Hannah excuse herself from one of the groups and bustle across to them. Her soft gray garment—certainly silk, for no other substance would flow so liquidly, and certainly designed and produced by Hannah herself, for fabric was her medium—fluttered with the breeze of her passage. The color matched her hair, the neck-to-ankle drapery camouflaged her grandmotherly figure, and the cut of the costume proclaimed her an artist as surely as Martha's tailored dress and Joe's suit and tie defined them as professionals.

Crying, "At last, at last," Hannah enfolded Martha in her arms, then released her and held out both hands to Joe. "And Mr. Gianni, of course. Lovely of you to come." Four months past her sixty-third birthday, she was as excited as a girl celebrating her sweet sixteen.

Martha, who had known Joe professionally for upwards of three decades, was accustomed to thinking of him as restrained beyond the average. But any New Yorker who has achieved a degree of worldly success has mastered cocktail party etiquette; Joe took Hannah's offered hands and air-kissed in the direction of her cheek. "Joe, please," he said. "It's very kind of you to have me."

"Oh, Joe, please, I'm the soul of kindness." The skin around her eyes crinkling, Hannah released his hands and linked arms with him and Martha. "Come, eat and make nice over the baby."

"The . . ." That did perplex Joe for a moment.

"The maquette," Martha cued him.

Earlier, when she'd granted his rather surprising request to accompany her to this reception, she had found it necessary to explain that a maquette was a small-scale model of a proposed large work of art. This one, whose display was the occasion for the party, represented the most recent stage of Hannah's autumn-blooming career: it was her entry in a competition for a large-scale sculptural work to be installed in a corporate space in Minneapolis.

"The maquette, of course," said Joe. "I'm looking forward to it."

The gray-painted concrete floor had been swept clean of the ravelings of thread and odd little fabric scraps that accumulated when Hannah was working, the industrial sewing machines at the side of the room were covered, and the caterer had disguised the big table on which Hannah cut out her patterns with a leaf-green cloth. They sampled properly runny Brie and trendily high-fiber crackers; then, carrying plastic glasses of better-than-tolerable wine, they began a meandering journey across the room, interrupted every few steps by introductions: two or three dealers; a writer from a slick-paper art magazine; a tall, fortyish man with a ponytail of gray-flecked mahogany-colored hair, who was talking with great intensity about the interplay of light and shadow to three women, two of them very young and very attentive, the third a stocky woman with Asian features whose smile said she'd heard it all before but didn't mind hearing it again.

The maquette, illuminated by a pair of spotlights on a ceiling track, stood on a blocky waist-high pedestal a few feet out from the far side wall. A bulky man in worn jeans and scuffed work boots was standing in front of it, his arms folded across his chest. Serious biceps bulged his T-shirt, and the overhead light created an aureole around his shaved brown scalp. It wasn't until he turned that Martha recognized him as a sculptor who, at his last opening, had been wearing an Al Sharpton haircut.

"Love," he said. He appeared to be addressing Joe.

Joe raised his eyebrows and sipped his wine.

"Joe Gianni, this is Dennison Simm," said Hannah. "Martha, I know you've met Dennie."

Martha nodded. Joe shifted his wineglass to his left hand, extended his right hand, and said, "How do you do."

Simm grasped the offered hand in a complex grip that might have had some street significance. "Do?" he boomed. "About like everybody else, I guess. Eat, drink, fuck, work. How about you, man?" It wasn't clear that he expected an answer; as he spoke, his gaze slid away across the room.

Nevertheless, Joe responded. His right hand still imprisoned, he produced a cocktail-party smile and said, "Well, I suppose that about sums it up."

The answer reclaimed Simm's attention. "Good man," he barked. He released Joe's right hand and slapped his left shoulder. Joe managed to extend his arm far enough to let the jostled wine miss his trousers and splat onto the floor.

"Love?" This time Simm was addressing Hannah. "Like gettin' married?" His voice slid up the scale into an Amos-and-Andy parody. "Maybe one a them tents they put up for a weddin' down on the ol' plantation? Keep the sun off all the massas an' missuses scarfin' up the mint juleps 'longside the magnolias?" But again his attention wandered across the room.

This time Martha let her gaze follow his. He seemed to be watching a young woman who was standing near the back wall, partly concealed by an abstract metal sculpture on a chest-high pedestal. Dredging the depths of her unreliable memory for names, Martha came up, first with Olive, and then with Quist. Olive Quist, who would be Olive Simm if she had chosen to take her husband's name.

Was Dennison Simm watching his wife or assessing the art?

Martha's judgment declared the woman to be the more worthy of attention. Her skin was the color of milky cocoa; her hair was teased into a dark froth around her head; her body, inside a red minidress, was nubile; her legs below the abbreviated skirt were shapely.

Obviously unaware of her husband's scrutiny, she was gazing into the middle distance. Once more Martha let another person's concentration direct her own gaze. While Dennison Simm was watching Olive, Olive seemed to be watching the ponytailed man who had been discoursing on light and dark, his three female listeners, and a second man, younger and slimmer, who had joined them. With lowered eyelids and curved lips, this newcomer was directing a stereotypically seductive gaze, not at either of the young women, one of whom was smiling in his direction, but at the Asian woman, who was ignoring him.

"Well." Simm returned his attention to Hannah. "Guess it's 'bout time to be gettin' on. Thanks for the invite, Miz Gold, ma'am." Once more he cuffed Joe, who this time avoided spillage altogether, and said, "Good to meet you, man."

When he had passed beyond earshot, Joe said, "Odd man."

"A good sculptor, though." Hannah spoke absently; most of her attention, like Martha's, was following Dennison Simm, who was heading for his wife. "Oh, child!" she breathed, "be careful!"

Olive had reached blindly toward the sculpture beside her and, still staring at the group in the middle of the room, was stroking a smooth area near its base. She was obviously unaware of Simm's approach until he was only a step away. He clamped his fingers around her wrist and jerked her hand away. The sudden motion rocked the sculpture on its pedestal. Almost absentmindedly, Simm steadied it with his free hand while with his other hand he twisted Olive's wrist at an angle that had to be painful.

Joe started forward half a step.

"Let it be," said Hannah.

Joe glanced at her and subsided.

And almost at once, the domestic drama turned anticlimactic. Simm transferred his grip from his wife's wrist to her upper arm; to anyone who had missed what had gone before, the grasp might appear as affectionate. Thus linked, they made their way toward the coatrack by the door.

The next act, if any, would take place elsewhere. Martha retrieved her attention and directed it to the maquette.

She had seen almost nothing of this work's progress, though she had heard much. Like many of Hannah's recent pieces, it was an arrangement of patterned fabric draped over a framework. What was new was its over-the-top lavishness. The maquette was much scaled down, of course; it measured about four feet high, three feet wide, and a couple of feet deep. The installed work was to be twelve feet high. The drapery would consist of hundreds of yards of hand-stenciled parachute fabric, whose folds would form passages leading viewers into a center chamber. There, a white linen cloth encrusted with embroidery would be draped over a lopsided structure resembling a misshapen altar. On this structure, securely fastened against pilferage, would rest a tattered stuffed object that vaguely resembled an emaciated teddy bear.

This creature, the altar cloth, and a scale model of the altar were displayed beside the maquette. A set of computer renderings that showed what a walk through the work would be like was mounted on the wall behind it, next to a blueprint of the armature, which was to be constructed of riveted and welded I-beams.

"Hi, Hannah, I'm sorry to be so late," said a voice behind them. "Hi, Martha." Wendy Kahane, Hannah's assistant until a few weeks ago, had arrived.

Wendy was somewhere between youth and middle age, thick-waisted and double-chinned, with a rebellious tangle of dark hair. Martha liked her a great deal.

"Oh, there you are!" Hannah said. Embraces were exchanged; Joe was introduced.

"So what do you think of Love?" Wendy demanded.

"Love?" said Joe.

"Love is its name," said Hannah.

"Oh. Yes. I see." Joe sipped his wine. "So if somebody wants to call it a wedding marquee . . ."

"Dennie is not stupid," said Hannah.

"Matter of opinion," said Wendy. Something behind them seemed to catch her eye; she said, "Oh, God," and began to sidle off. "I'll talk to you later, Hannah."

Martha turned. A young man—the one who had joined the group to which Olive Quist's attention had been directed—had left that group and was approaching.

"Don't run away," Hannah called after Wendy. "We're going to dinner."

Wendy looked back over her shoulder, glanced once more at the newcomer, and raised her eyebrows.

The snub was obvious, but the young man's smile did not waver, although his eyelids flickered for an instant.

Hannah reasserted control. "Martha, Joe," she said, "this is my new assistant, Kent Reed. Kent, my dearest friend, Martha Patterson, and her friend Joe Gianni."

So this was Kent Reed. Martha had heard a good deal about this beautiful young man (Hannah's epithet) who was Wendy's replacement, but this was their first meeting. She offered her hand and said, "How do you do." Beautiful was not an exaggeration; he was tall, loose-limbed, and high-cheekboned; his skin was a shade between cafe au lait and pale beige; he wore his hair in a neat modified Afro.

"Martha, what a treat," he murmured. He didn't exactly shake her offered hand; he gave it a squeeze that was probably meant to flatter with a hint of affection. Perversely, Martha was simply annoyed. He said, "I've heard so much . . ."

"And," Hannah repeated, "her friend Joe Gianni."

Instantly obedient, he released Martha's hand and modulated his manner from charm to good fellow. "Mr. Gianni," he said. "Joe. How are you?"

Sepia. That was the word for the beautiful young man's skin color.

Joe's right hand had found its way into his coat pocket. He left it there, nodded, cleared his throat, and said, "Fine. And you?"

Kent nodded at the maquette. "Isn't it marvelous?"

Joe cleared his throat once more and said, "Impressive."

And there the conversation stalled; no one seemed to have anything more to say. As speechlessness engulfed them, Hannah stood with her hands folded loosely in front of her, a thoughtful line etched between her brows. She might have been conceiving a new work to be called Awkwardness.

And all at once an imp sprang forward from the lawless recesses of Martha's mind. "You must be an artist, Kent," she said.

"Ah, well," he said. "I aspire."

Ah, well? Good heavens. Martha looked across

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...