- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

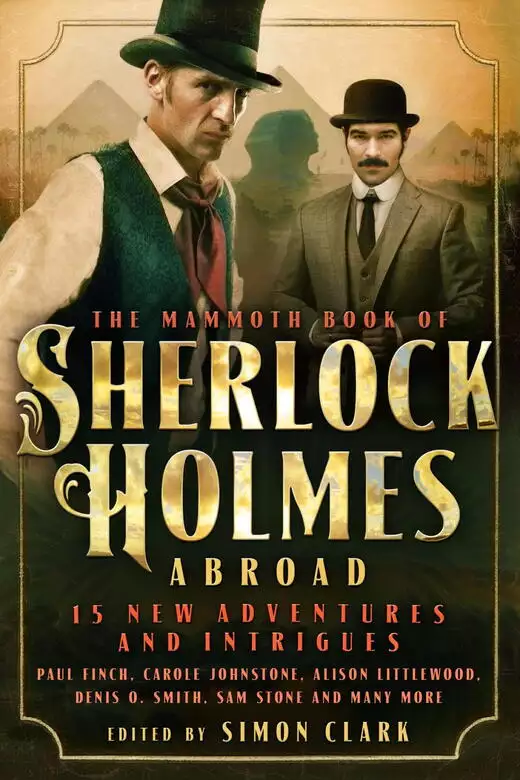

In this wonderful anthology of new stories, Sherlock Holmes travels to the far ends of the Earth in search of truth and justice. A host of singularly talented writers, while remaining respectful towards Conan Doyle's work, present a new and thrilling dimension to Holmes's career. Full list of contributors: Simon Clark; Andrew Darlington; Paul Finch; Nev Fountain; Carole Johnstone; Paul Kane; Alison Littlewood; Johnny Mains; William Meikle ;David Moody; Mark Morris; Cavan Scott; Denis O. Smith; Sam Stone and Stephen Volk.

Release date: April 2, 2015

Publisher: Robinson

Print pages: 512

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Mammoth Book Of Sherlock Holmes Abroad

Simon Clark

My thanks go to the Sherlock Holmes expert Charles Prepolec. Thank you, also, to Mike Ashley for his encouragement and help. Mike edited The Mammoth Book of New Sherlock Holmes Adventures (Robinson Publishing, 1997); in doing so, he set a very high standard in the finding and the gathering together of “lost” cases. And much gratitude to Duncan Proudfoot, Emily Byron and Georgie Szolnoki at Constable & Robinson for making this anthology possible in the first place.

I would like to thank you, the reader, for your undiminished appetite for new Holmes and Watson adventures. Happily, I share that appetite, too. I also whole-heartedly thank my wife, Janet, for her advice and feedback as I recruited such a fine team of writers and compiled this volume that you now hold in your hands.

All of the stories in this anthology are in copyright. The following acknowledgements are granted to the authors for permission to use their work herein.

INTRODUCTION © 2014 by Simon Clark, and THE CLIMBING MAN © 2014 by Simon Clark

THE STRANGE DEATH OF SHERLOCK HOLMES © 2014 by Andrew Darlington

THE MONSTER OF HELL’S GATE © 2014 by Paul Finch

THE DOLL WHO TALKED TO THE DEAD © 2014 by Nev Fountain

THE DRAUGR OF TROMSØ © 2014 by Carole Johnstone

THE CASE OF THE LOST SOUL © 2014 by Paul Kane

THE MYSTERY OF THE RED CITY © 2014 by Alison Littlewood

THE CASE OF THE REVENANT © 2014 by Johnny Mains

THE CASE OF THE MALTESE CATACOMBS © 2014 by William Meikle

A CONCURRENCE OF COINCIDENCES © 2014 by David Moody

THE CRIMSON DEVIL © 2014 by Mark Morris

THE ADVENTURE OF THE MUMMY’S CURSE © 2014 by Cavan Scott

THE ADVENTURE OF THE COLONEL’S DAUGHTER © 2014 by Denis O. Smith

THE CURSE OF GUANGXU © 2014 by Sam Stone

THE LUNACY OF CELESTINE BLOT © 2014 by Stephen Volk

Holmes and Watson run across the moor. Fog swirls. The eerie howl of a gigantic hound . . . Mystery and excitement all but crackled from the television screen, and I, at eight years old, sat on the edge of the chair not wanting to even blink in case I missed one marvellous second. The film and television adaptations of the Sherlock Holmes stories provided me with my first introduction to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s legendary detective – and the film that long ago captivated me and transformed me into a devotee of Sherlock Holmes was the 1959 Hammer production of The Hound of the Baskervilles, starring Peter Cushing.

A few years later, I began to read the Conan Doyle stories in a little old book with red covers that I found in a tin trunk at my grandparents’ house. I still have that book, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, published by T. Nelson & Sons. It’s here beside me on my desk as I write this introduction. A handwritten note on an otherwise blank page before the title page tells me that the book was bought by F. Audsley on 20 May 1918. The red volume’s diminutive size suggests it was specially produced for those serving in the military, so it could be slipped into an army overcoat, perhaps, before its owner headed out to the trenches of the First World War in Europe. In my mind’s eye, I can see Mr Audsley finding a few precious moments to escape his nightmarish surroundings by reading exciting adventures, involving a man with a twisted lip, or the red-headed league, or a scandal in Bohemia, while artillery thundered, and bullets flew overhead.

I don’t know who Mr Audsley was, exactly, who indirectly bequeathed me The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, but the book has been a good companion to me over the past forty years or so. I loved the adventures that Holmes and his friend, the ever-loyal Doctor John Watson, embarked upon. Yes, I liked the parts where Holmes receives visitors to his Baker Street rooms, and makes his astonishing deductions based on how the sole of a boot is worn, or the singular position of an ink stain upon a sleeve. But what really made my blood race with excitement was when Holmes would urge Watson to pack his bag, collect his revolver, and check the train timetables for some destination where the drama would explode from the page.

Holmes would then unravel the mystery and identify the culprit, with, as likely as not, an arrest to follow, bringing everything to a satisfying conclusion. When Holmes and Watson ventured to remote parts of Norfolk or Devon these would, to many readers of the time, seem quite outlandish and strange – places that could contain lurking danger in the form of ominous figures prowling the countryside, or oozing marshes that might claim the city gentleman who wandered too far away from the path.

Holmes travelled further afield, too, of course. “The Final Problem” sees him venture across the sea to mainland Europe, eventually reaching the terrifying Reichenbach Falls in Switzerland – it is here where he experiences his fateful and seemingly catastrophic encounter with the evil Professor Moriarty.

It was this notion of Holmes travelling away from the cosy surroundings of 221b Baker Street that prompted me to suggest to the publisher of this book that I compile an array of short stories that sends Holmes out of London and away from Britain to countries overseas. The exotic places would provide an unfamiliar setting for mysteries that would test Holmes’s ingenuity. What’s more, the very landscapes themselves would test him, too, when he found himself in extremes of heat and cold, and, perhaps, faced by local populations that were hostile to the Englishman.

The publisher liked my idea and gave me the go-ahead for The Mammoth Book of Sherlock Holmes Abroad. I immediately invited a range of authors who I knew could pen fiction that was entertaining as it was imaginative and would still be respectful towards the legacy created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and satisfyingly echo the style of the original works. I recruited writers, however, that would be prepared to take risks, and transport Sherlock Holmes “abroad” in, perhaps, more senses than one. Consequently, not only does he travel to exotic locations in these pages, he also encounters mysteries that are equally exotic, and severely test his powers of deduction.

Within this book you will find several tales that are very much traditional Sherlock Holmes adventures, in the sense that they wouldn’t have been out of place in The Strand of a hundred years ago, the magazine that first featured Sherlock Holmes. Others in this volume will challenge the reader, just as certain Conan Doyle tales would have raised eyebrows and increased the temperature of the flesh beneath those stiff collars of Victorian and Edwardian Britain.

It must be said that our detective hero also experimented with drugs. These, on the whole, were legally obtainable in Sherlock Holmes’s “time”. It wasn’t until the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1920 that a wide range of narcotics, including cocaine and opium, were banned in Britain. Therefore, we can easily imagine Holmes “travelling” to fantastical destinations without ever leaving his armchair. Indeed, Doctor Watson observes his friend rising “out of his drug-created dreams” in “A Scandal in Bohemia”. Where the drugs carried Holmes in those dreams we don’t know, but in this volume you’ll find him, on at least one occasion, “transported”, let us say, and possibly influenced, by certain chemicals that he was so fond of injecting into his veins, or smoking in his pipe.

Other writers in this volume give Sherlock Holmes more conventional modes of transport: locomotives, horse-drawn carriages, sailboats and steamships. Nonetheless, these convey him to faraway realms where he encounters mysteries and adventures galore.

I hope you enjoy accompanying Mr Sherlock Holmes, as he steps out from his rooms in London’s Baker Street, and ventures abroad on these extraordinary journeys.

Bon Voyage.

Simon Clark

September 2014

The sun dipped as we approached the mountain range. The rugged peaks of the Nandi Hills glinted flame-red, lilac shadows flowing like ink across the flat green/gold scrubland lying betwixt us and the eastern slopes of those majestic highlands. Of course, beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and all the time I’d known him, my friend, Mr Sherlock Holmes, had never once been stopped in wonder and awe by anything picturesque. Even now he leaned against his armrest, absorbed in thought, the dusty white brim of his homburg pulled down over his eyes, drawing on a cigarette he’d unconsciously taken from the engraved silver case donated to him in gratitude after the stressful business at Mortmain Manor.

In truth, the romance of our setting could be exaggerated. The last two days had been arduous even by the standards of our recent travels. The horse that pulled our trap was a bony nag, its sagging posture and stick-like ribs suggesting a painful need for food and water. As such, we made laborious progress even though our road ran straight as an arrow. This was a service road, and better than many others we’d encountered in the East African Protectorate. It ran parallel to the railway tracks, only a dozen yards of dry earth separating us from the neatly arrayed sleepers and sun-gleaming metals. If nothing else, this was a welcome trace of modernity in a hot, harsh wilderness; firm evidence that civilization, at least as we British knew it, was finally pushing north through the Great Rift Valley. But it also underlined the sheer vastness of these spaces, and answered the oft-asked question as to why so mammoth a series of tasks had ever been undertaken in East Africa in the first place.

The Ugandan Railway, as the press at home christened it, had been completed five years earlier, forging an unbroken line of communication for almost seven hundred miles between Mombasa on the Indian Ocean and Kisumu on the east shore of Lake Victoria, to much acclaim but at staggering cost. This new branch line, originating at Kalawi Junction, a middle-of-nowhere former army outpost now turned crossroads town, drove away from it at a right angle towards Lake Rudolf, and had encountered similar problems: swamp, jungle, rocky ridges minus tunnels, depthless ravines minus bridges, and of course fierce wildlife and hostile tribesmen.

The portion of the route we were traversing now, which one could probably characterize as savannah, was less overtly dangerous, but, though scenic, monotonous. It changed little as we traversed it hour after uneventful hour. Our driver didn’t help. His name was Jervis, and he’d been a lance corporal in the King’s African Rifles. Now – at sixty-five, I estimated – he was too old to be of service. That notwithstanding, he’d remained here in the Protectorate, seeking what work he could, and as such was completely acclimatized. Even in the raging heat of a bone-dry February, his short, stooped form was shrouded in a double-caped overcoat, with a scruffy, moth-eaten cap hanging sideways from his head. He was a pucker-mouthed, pockmarked man, wizened and browned to the texture of a walnut. I’d attempted to engage him in banter, regaling him with a few military quips of my own, but his monosyllabic responses had not encouraged me to continue.

I adjusted my position for what seemed the eightieth time. It wasn’t easy finding comfort on a wooden plank only thinly clad with ox-hide. I irritably addressed the yellowed copy of The Times I’d managed to acquire at Kalawi. It was dated December 1905, which meant it was only three months out of date – something of a blessing in this part of the world. But its front page made the usual gloomy reading.

As a continued aftermath of the Boer War, the reconstruction process was costing the British taxpayer ever more money. Not only had the initial three million pounds allocated to cover the resettlement of Boers displaced from their farms in the Transvaal or the Orange Free State, or interned in those terrible prison camps, now been used up, another three million had been earmarked in the way of interest-free loans to provide landowners with the means to replace their crops and livestock; and now it seemed another two million was to be forwarded as compensation to neutral foreigners and native blacks who’d also suffered. As a prominent MP who had opposed the South African campaign said, who knew where it was going to end?

“What did you make of Meinertzhagen?” Holmes asked me, unexpectedly.

I shrugged. “I imagine he’s the kind of chap who gets what he wants.”

“Most certainly.” Holmes relapsed into thought again, though my brief, rather inane observation couldn’t have added much fuel to that process.

The Meinertzhagen in question was Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, under whose remit protection of the new railway project fell. On first meeting him at Kalawi, I’d thought him a rather typical pillar of colonial officialdom; an army officer by name, but in reality occupying that mysterious middle-ground between soldier, bureaucrat and sportsman that one tended to find over here. He was tall, straight and handsome, civilized in all his manners, undoubtedly well bred, and yet an unbending kind of man, with hidden depths of toughness. We’d met him in one of the stable paddocks attached to the Kalawi barracks. He’d been clad for the outdoors in a staff officer’s fawn tunic, jodhpurs and tall, well-polished riding boots, and was standing legs apart and crop in hand as he barked instructions at a group of boys engaged in breaking a succession of spirited horses. Almost inevitably, he’d seemed unflustered either by heat or dust.

“Is he the sort of man,” Holmes said, “who would stay his hand if . . . say, if it came down to it?”

“Well, it has come down to it, hasn’t it?” I replied. “And he didn’t.”

Holmes acknowledged this without speaking. I was referring to the events of five months previously, when twenty leaders of the Nandi nation, the native occupants of this region, having risen under arms against the railway’s intrusion into their tribal homeland, had been lured to a peace negotiation by Meinertzhagen, only to be machine-gunned en masse. A single bullet fired from Meinertzhagen’s own Mauser pistol had claimed the life of Koitalel Arap Samoei, the Nandi’s supreme leader.

“That said,” I ventured, “the publicity was hardly good. I doubt he’ll want any further kerfuffle with these local chaps. Which I presume is why we’ve been called in.”

“Well, of course.” Holmes’s tone implied surprise that I thought this a remarkable enough point to raise. “I’ve no doubt that very fact lies at the root of all these recent murders.”

“Not this mysterious monster we’ve heard so many mumblings about?” I said.

“Oh, I wouldn’t be sure of that, Watson. You’ve travelled the Empire to its limits. You don’t need me to tell you how intimately involved with colonial politics monsters can be.”

“Pleased to meet you, Mr Holmes . . . it’s a great honour.”

The overseer’s name was Alex Butler, and again he was just what I’d expected a white settler to look like out here. He was deeply tanned, and though a head taller than either myself or Holmes, burly with it – to the point of being four-square. He had a bull neck, a jutting jaw and a thick black beard. His weatherworn khaki tunic fitted him tightly, though his sleeves were rolled back to the elbows, exposing ham-like forearms covered in brush-bristle hair. He wore a wide-brimmed bush hat, tied under his chin with a leather thong, and two criss-crossing bandolier belts filled with ammunition. What looked like a beaten-up Martini-Henry rifle was slung at his shoulder, twenty or so tiny notches etched into its butt, a huge acid scar on its lock. Despite his ferocious appearance, Butler grinned broadly, showing even rows of white-yellow teeth. He shook our hands with strength and vigour.

“Welcome to Hell’s Gate – at least that’s what the boys have been calling it, thanks to us losing so many souls as we approached. Its official name is the Tungo Gorge.”

For the last twenty minutes, Jervis had driven us virtually alongside the railway, up a shallow gradient through a forest of whistling-thorn so closely interlaced that the setting sun had barely penetrated it. Above, the entangled spiny boughs had formed a low ceiling, which I fancied would claw the paint from the roof of any passing train. Immediately after that we’d entered the aforementioned gorge, a colossal crevice in the Nandi Hills running south-north, which we’d traversed half the length of before we’d finally encountered the construction crew.

It was well after dark, but in the infernal firelight of multiple torches, rugged walls of red rock rose sheer on either side. Only a slice of star-speckled African sky was visible overhead.

“Your boys don’t seem to care for it very much,” Holmes remarked, thinking on the groups of native men we’d seen headed east on foot, weighed down with tools and backpacks, as we’d finally reached the whistling-thorn. Those gathered around us now numbered only thirty or so, the African features of the Nandi alternating with the paler Asian faces of coolies imported from the Subcontinent. To a man, they looked tense, nervous, and yet their eyes shone with fascination at the sight of Holmes. His arrival had no doubt been trumpeted for several days.

“That’s easy to explain, gentlemen,” Butler said. “There were two more murders this evening. That makes sixteen in total in the last month.”

“Are the corpses still lying where they were found?” Holmes asked with immediate interest.

“Afraid not, Mr Holmes, sir,” Butler said. “Leave dead meat out here for long, and the scavengers are all over it. McTavish has assigned one of the tents at the far end of the works as a temporary mortuary.”

“McTavish?” I asked.

“Our chief engineer, Dr Watson.” Butler said this with a degree of disdain, which he quickly realized we both had noted. “Forgive me, gentlemen. Robert McTavish clearly knows how to build a railway . . . but, well, I sometimes wonder if this is really the place for a minister’s son.”

“You think he’d rather be saving souls than hammering spikes?” Holmes asked.

Butler smiled to himself. “I wouldn’t go that far, Mr Holmes, but there’s much of East Africa still needs taming, and sometimes that requires a firm hand. Anyway, you must look at the bodies . . . of course you must. But if you feel like resting first, that might be an idea, especially if you’re planning on eating.”

“No time for rest,” Holmes said, indicating that I should take care of Jervis, who, once I’d paid him, stated flatly that he was heading home straight away and wouldn’t be returning. Apparently supply carts arrived from Kalawi Junction on a two-weekly basis. When we were done, we’d “need to hitch a ride back with one of them”.

“And who’s to worry if we must first dawdle around here a few days,” I said, in a huff, as Holmes and I, laden with bags, followed Butler along the remainder of the gorge on foot.

“I doubt there’ll be much dawdling, Watson,” Holmes replied curtly. “The fear in this place is palpable.”

The few labourers remaining made space for us as we walked through. Some wore shorts or loincloths, though most were clad in loose-fitting rough-wear. Even though it was night-time the heat was unrelenting. Drab, dusty tents were everywhere, along with piles of raw materials, filling the gorge on both sides of the railway. There was also the construction train itself. This consisted of at least twenty open wagons loaded with metals and timbers. Though the locomotive was located at its rear, it was turned around, the idea being that it would push the train forward slowly as the tracks were laid, so the cargo was always delivered to the point of need most swiftly. As we passed the footplate, the driver and his mate, both Indians, remained onboard, watching us warily. One wore a Webley pistol in a harness, while the other clung to a two-handed spanner.

“They are not happy,” I agreed.

“What do you know of the Nandi Bear, gentlemen?” Butler asked over his shoulder.

“Precisely nothing,” Holmes replied. “Please feel free to enlighten us.”

“In Nandi mythology, it’s a great brute of a bear . . .”

“Of which there are no known wild species native to any part of Africa,” Holmes said.

“Correct, Mr Holmes.” Butler sounded impressed. “But even if wild bears were found in this part of the world, that’d be irrelevant. The Nandi Bear is a kind of spirit beast.”

“A tribal totem?” I suggested.

“A bit more than that, Dr Watson. A guardian spirit. At least, in the Nandi belief.”

We’d now reached the end of the train. Beyond it, the gorge was filled with opaque blackness. But initially our attention was drawn elsewhere – to a large tent on our right, standing separate from the others.

“It’s this beast,” Butler said, lifting the tent flap, “which, according to the rumours, is killing our workforce.”

We entered and, by the light of a suspended lantern, saw two naked corpses lying on parallel tables. Both were local Africans: tall, well-built chaps. Butler told us the one on the right was Torokut, who had been the construction camp foreman; the other was Abasi, one of his labourers. Both had been terribly mutilated, their bodies slashed and torn from head to foot.

“I’m afraid you can’t see the others,” Butler said. “We’ve either sent those back or had them buried along the way. Local sensitivities and all that.”

“Have only Nandi workers died?” Holmes asked, assessing the evidence in his usual unemotional way.

“No, Mr Holmes. We’ve lost several coolies too.”

“So this is a message for everyone,” Holmes said under his breath. “You say these two attacks occurred earlier this evening?”

“Shortly after eight. We’ve been falling behind badly. Torokut took it on himself to put in extra time. He and Abasi were working alone just a way up the gorge from here, trying to clear scrub that we’d torched during the day. A couple of the other boys heard their screams, but they were too frightened to investigate. I was down the other end of the train at the time. When I got there, it was all over.”

“Well, these fellows haven’t been murdered,” I said, and I honestly believed that at the time. “They’re clearly the victims of an animal attack. I’ll need to make a proper examination to ascertain the exact cause of death, but at first glance there are any number of possibilities. Throats bitten, skulls crushed, evisceration of the lower abdomen. The signs are obvious.”

“And that can’t be unusual in a region like this?” Holmes said, posing it more as a question than a statement.

Butler shrugged. “Unusual enough for Colonel Meinertzhagen to have paid your fares all the way down the east coast and across the interior. Unusual enough for him to have sent to Mombasa for additional troop numbers, once they’re available.”

“You don’t have lions and leopards in this part of the country?”

“We certainly do, Mr Holmes. The lion attacks at Tsavo impeded the mainline railway’s construction for quite a few weeks. But there’s no evidence there are big cats in Tungo Gorge. Or that they’ve attacked any of our men. Big cats kill to eat – even if disturbed, they drag their prey away afterward, or devour as much as they can on the spot. None of our casualties were in any way eaten. On top of that, I’ve farmed several thousand acres in the Lumbwa highlands for quite a few years now; I’ve guided prospectors, hunting parties, missionaries. I know my lions and leopards. I’m used to their spoor. I’d stake my life on there being no big cats around here at present. We even set lion traps when we were out on the plain, but caught nothing.”

“Even so,” I protested, “this is a dangerous place. I’d expect every man to carry his weapon of choice, and yet I only saw one of your chaps armed with a gun.”

Butler shrugged again. “We have to be wary of that, Dr Watson. Some of the boys we know and trust are allowed guns. Mainly coolies. The problem is the Nandi. They were in open revolt only recently. To equip them with firearms would be a big risk. As an extra precaution, only I have keys to the ammunition store, which is the compartment right at the front of the train. No one else is allowed in there but me.”

“Not even Engineer McTavish?” Holmes asked.

“McTavish has his own little kingdom – the explosives store.”

“You’d think a king with explosives to hand would be a force to reckon with, eh?” came a feeble-sounding Scottish voice from the entrance to the tent. “Truth is, I feel anything but.”

This was our introduction to Chief Engineer Robert McTavish. And a less than inspiring one it was. My immediate impression was of a fussy man who back in civilization would be preened and dapper, and yet here had allowed heat and exhaustion to get the better of him. Like Holmes and me, he was clad in tropical whites, though they were grubby and creased. He was of short, tubby stature, his paunch hanging over his belt buckle from an open waistcoat, his hair a greasy red-grey thatch, which hadn’t seem a comb in days. The top of his lengthy nose was pinched by a lopsided pair of pince-nez, but perhaps the most startling thing about him was his half-beard. He had a full red moustache, but only one side of his lower face wore whiskers, though these were dabbled in lather, so he’d evidently been in the process of shaving. The other side of his jaw was clean, but cut in several places, blood dribbling freely onto his collar.

“Apologies for my ghoulish appearance, gentlemen,” he added. “I only just heard you’d arrived. Plus—” he offered us a shaking hand “—I’m not as steady as I once was.”

Formal introductions were made, at the end of which McTavish shook his head wearily. “So what do you think of our horror show?” he asked.

“I suspect an animal attack of some sort,” I stated again.

McTavish smiled. “You think we’ve never experienced that kind of thing out here, Dr Watson? Trust me, I wish that was the answer, then we could snare and shoot the rogue beast responsible, just as they did on the Tsavo River.”

Before I could reply, Holmes spun to face Butler. “You told me these men were heard screaming as they died. You didn’t mention any animal sounds – no roars, snarls?”

“Nothing of that sort, Mr Holmes,” Butler replied.

“Nothing,” McTavish echoed disconsolately.

Holmes gave this brief thought. “And that’s something we can’t disregard, Watson, no matter how it may muddy our waters.”

I had to admit, this odd fact needed explaining. In India, I’d known tiger attacks where the predator made no sound initially, but if it turned into a struggle, as this one surely must have with two victims involved, there were almost always growls. Besides, there are no tigers in Africa.

“Time we looked at the murder scene,” Holmes said.

Butler took the lantern, and we moved out of the tent. Much of the camp now lay at our rear, but was largely deserted, the majority of the workforce having retreated to their beds. Alongside us stood the front three carriages of the train. The first was a rudimentary but fairly standard railway compartment, which, after its years of service on these sun-wizened hinterlands, looked understandably weather-worn. According to McTavish, this one contained the works office. The second compartment was sealed, its few windows shuttered and bolted, the shutters bearing warning insignia for explosives, though several of its air vents were fixed open with screws. The third and last, the ammunition store, bore no markings but this too was closed up except for several air vents, which had also been screwed open.

Our eyes had now attuned to the equatorial darkness, and we could see that north of this point, the railway line ended in dust. From here on the gorge was filled, initially with burnt and blackened vegetation, but beyond that with lush, tangled thorns and deep grasses, some reaching to shoulder height and above. We advanced into this along a footpath flattened through the stubble. Butler led the way with lantern held high and rifle unslung. On reaching the clearing where the double attack had taken place, it immediately struck me as worrying how close it was to the main camp. Thirty yards from the end of the train, no more. Here, the burned foliage thickened up again, interspersed with patches untouched by flame, but it offered no real screen. It seemed that only superstitious terror had prevented the rest of the workforce coming to the doomed pair’s aid.

On entry to the actual clearing, it didn’t require Holmes’s sharp eye to conclude that violence had been done. Both charred and fresh vegetation alike had been trampled and torn, the sunbaked earth kicked up in divots. And there were spatters of gore everywhere.

“So close to safety and neither one of two strong men was able to escape,” he remarked, thinking aloud. “Our assailant came upon them with great speed and ferocity.”

“Every death has been like this,” McTavish said in the tone of a man at the end

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...