ONE

There are things I cannot say in any voice.

I was born Leonora Emmaline Somerville, but I am not at all sure that is still who I am.

Oh, I could tell you the facts as you will find them in The Examiner and The Times and the Morning Post. I could tell you which Illustrated London News artist depicted the burning masts most faithfully, which Royal Academy painter best captured the hurricane of light reflected on black water. But I could not tell you where to find me in their pictures, or even which of the facts are reliable when it comes to me.

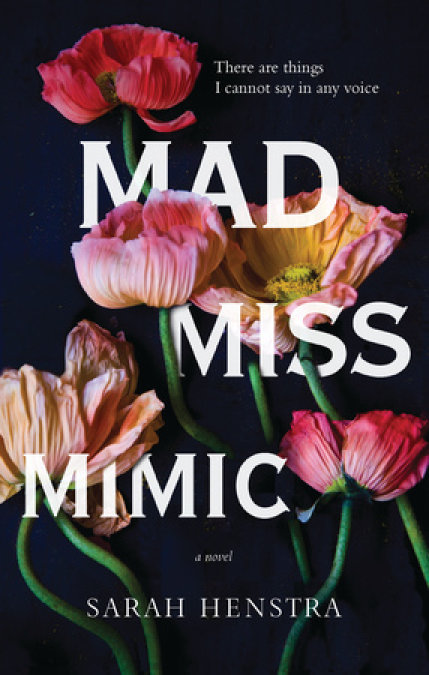

“Miss Somerville,” they called me to my face at Hastings House, and “Mad Miss Mimic” when they thought I could not hear. Which is the more accurate name for me? My sister always said that one’s station determines who one is. Certainly she believed it her life’s noblest task to secure my station through a good marriage. She did believe it, and she did try—I must grant her that at least.

My aunt Emmaline says that your story decides who you are. But what about the chapters I did not write? Those scenes in which I stood by, watching in horror, but found nothing to say? Those moments when my tongue froze, and I tasted ashes and could not produce a single word?

If I am not visible in the pictures of the Thames disaster, it must be because I am still under water. I’ve long given up thrashing for the surface and fighting for breath. The current turns me in its bed like an efficient nurse, shifting my limbs and nudging me and whispering me to sleep. Sweeping me down, down, out to sea.

Oh Aunt Emma, how can you ask me to recover the traces of my story from the wreckage? I am still in the river, caught here in the undertow of grief.

Spilled slops, and a housemaid’s illness. A lowly beginning for a tale to be sure! But looking back I think that must be when it really began for me. A morning in early March—a cold morning between winter and spring, the kind with dull grey light outside the window and rain hissing down the chimney onto the coal-grate. The kind of morning that asks you to linger in bed instead of rising to greet the day.

I was only half-dressed when Hattie’s accident happened. My lady’s maid, Bess, had gone to fetch my hairbrush from my sister’s room. A sharp clang of metal on wood echoed from the service stairs, followed by a feminine cry of distress. Afraid that Bess had fallen I ran down the hall to assist her but discovered Hattie instead. The servant girl was stopped halfway down the narrow staircase, strug- gling to right a copper bucket and gather the hearth brush and tray she’d dropped. I hadn’t seen Hattie often in my eighteen months at Hastings House. The lower servants kept their own schedules and stayed in separate quarters. Hastings is large for a city home: a cold, cavernous maze of a house with thirteen bedrooms, a greater and a lesser hall, and two libraries in addition to the usual parlours, eating rooms, nurseries, and kitchens. The regular staff of eleven grew to sixteen or twenty when my sister planned one of her parties. So I knew nothing of Hattie’s background or character—to me she was only a shy housemaid, maybe thirteen or fourteen years old.

The spreading stench told me the contents of the tipped bucket: the girl must have just finished emptying the family’s chamber pots. I shivered in my chemise and would have turned back to avoid embarrassing her, but I was surprised by the violence of Hattie’s trembling and the whiteness of her knuckles as she gripped the banister for support. The slops pail slid farther from its precarious balance against her knee. It looked like she might fall. Hastening to Hattie’s side I steadied the pail and seized her round the waist. She was so thin that I could feel all her ribs.

“Sorry, mum,” Hattie gasped, and then she paled even further: “Oh, I ain’t to be seen by the family carryin’ slops, mum! I beg you, mum, please leave me.”

“Shh,” I soothed her. “Shh, now.” I was composing a joke about my baby nephew’s soiled diaper, which had rolled nearly to the landing, and I might even have attempted to tell the joke for Hattie’s sake, but we were interrupted by the appearance of Mrs. Nussey through the door below us.

“Hattie! What is the meaning of this?” The housekeeper hiked her skirts and lumbered up the stairs.

I smiled at the woman, about to tell her that I wasn’t the least bit upset, that the poor housegirl was near to fainting from shame and fear.

But Mrs. Nussey was gaping in open-mouthed horror at my feet. “Miss Somerville! Your slippers are ruined. Do remove them at once!”

“S-sorry m-m-m ...” I stammered. “I only m-meant ...” But my tongue had fixed itself like a bar of lead in my mouth. I sat down right there on the stairs and tore off my urine- stained slippers.

“Whatever are you doing, wandering about undressed?”

I kept my head down so that my hair would fall and screen the flush on my cheek.

Concern sharpened the housekeeper’s voice: “Miss Somerville, are you quite well? Shall I call for Dr. Dewhurst?” I shook my head and, so that she would not fetch my brother-in-law, I forced myself to meet Mrs. Nussey’s eyes. And there it was, plain as day: that expression I knew so well but still cringed every time to witness. The eyes darting all over my face, the mouth tight with anticipation. Wary but fascinated. Waiting.

What was I to do? I knew that if I did not speak for her Hattie would be punished—unfairly, since she was obviously ill—but my embarrassment and fear of self-exposure made me creep, barefoot and shamefaced, back up the stairs. I winced when I heard the housekeeper’s slap and Hattie’s suppressed cry, but I did not turn around.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved