Lydia

- eBook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

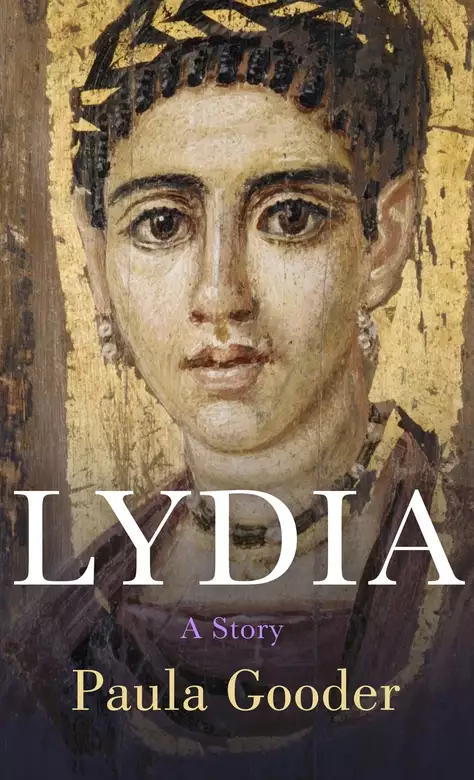

Synopsis

The New Testament tells us very little about Lydia, a seller of purple cloth who was living in Philippi when she met the apostle Paul on his second missionary journey. And yet she is considered the first recorded convert to Christianity in Europe.

In her second work of fiction, Biblical scholar and popular author and speaker Paula Gooder tells Lydia's story - who she was, the life she lived and her first-century faith - and in doing so opens up Paul's letter to the Philippians, giving a sense of the cultural and historical pressures that shaped Paul's thinking, and the faith of the early church.

Written in the gripping style of Gerd Theissen's The Shadow of the Galilean, and similarly rigorously researched, this is a book for everyone and anyone who wants to engage more deeply and imaginatively with Paul's theology - from one of the UK's foremost New Testament scholars.

Release date: October 6, 2022

Publisher: John Murray Press

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Lydia

Paula Gooder

Lydia was the opposite of joyful. The midsummer sun beat down relentlessly, its suffocating heat leaving her no option but to pant like her father’s elderly dog. Sweat covered every inch of her body. Her head pounded. Her vision swam, though it was hard to tell whether this was due to the sweat dripping incessantly into her eyes or to the baking heat shimmering upwards from the interminable Via Egnatia, which snaked onwards as far as her blurry eyes could see. Then, to cap it all, the ache that had lodged determinedly in her hip ever since the cart rumbled out of Neapolis the morning before, began seeping upwards and outwards, heading for the small of her back. Lydia shifted her position irritably, letting out a small, undignified grunt as she did so.

‘Let me guess,’ the dark brown eyes of the young woman sitting opposite her twinkled mischievously, ‘you’re too old for this?’

Lydia shrugged her acknowledgement. Even through the fog of her toweringly bad mood, she had to admit that this phrase had hung almost constantly on her lips since their small party had departed Thyatira a few weeks earlier.

Ruth, her brown-eyed companion, became suddenly serious. ‘When are we going to talk about the real reason you didn’t want to come?’

Lydia sighed. ‘I hate it – the travelling, the upheaval, the discomfort . . . all of it.’

Ruth moved to sit on the bench next to her and settled back with an exasperating appearance of comfort on the same hard wooden bench that was causing Lydia so much pain, her fluidity of movement suggesting that she would never be too old for . . . well . . . anything. ‘It’s a reason, but it isn’t the reason, is it?’

From his position at the front of the cart, John snorted and mumbled something inaudible. The horses picked up speed obediently in response, but Lydia had a suspicion that whatever he’d said was meant not for them but for her.

It was true that she had never felt as old and tired as she had in the past few weeks. The more excited and animated Ruth appeared at what lay ahead of them, the more stifling Lydia’s sense of dread had become. Fear crept into every corner of her waking mind and, most nights, her dreams too. Each morning she would wake exhausted, hardly any more rested than when she had gone to bed.

She should have said something all those weeks ago when it became clear that someone had to go to Philippi. Alexander, their faithful steward, who had taken over when Lydia had had to leave so suddenly all those years ago, had fallen ill and died suddenly. Over the years, he had run the business with such a graceful competence that Lydia hadn’t had to think much about it. But now he was gone, and with him the much needed income from Philippi’s love of all things purple. Someone needed to be there to run the business, and, try as she might, Lydia hadn’t been able to think of anyone else who could go. Her father really was too old to travel, and in any case was so deeply involved in the dyers’ guild of Thyatira that to remove him from it would have been like losing a limb. After the deaths of her three younger brothers and two sisters in their infancy, and then of her mother in a final ill-fated pregnancy, Lydia and her father had clung together and slowly remade their lives. The reality was that there was no one else to ask. Like it or not, Lydia would have to go. She’d made a half-hearted attempt to persuade Ruth to stay in Thyatira with her father, but her pleas had not worked. From the moment when they’d fled Philippi with only the clothes on their backs nearly ten years before, Ruth had barely left her side. And since Lydia found it impossible to put her sense of foreboding into words, how could she have made a case for Ruth to stay behind?

So she had kept silent, and had – or so she had thought – kept her fears to herself. Now Ruth’s inquisitive eyes and John’s censorious back suggested that she had been less successful than she had imagined. But how much did they know? John had lived all his life in Thyatira working alongside her father and becoming highly regarded as an expert dyer of purple; Ruth had been only a child when they had left Philippi, and so, Lydia sincerely hoped, remembered little of the events that had driven them out. After arriving back in the safety of her home town and sinking into the peaceful embrace of familiar sights, sounds and rhythms of life, Lydia had never mentioned the turbulent events to anyone, priding herself on a well-kept secret; her status as a brilliant businesswoman safely intact in everyone’s mind but her own.

As they had drawn nearer to Philippi, Lydia watched Ruth for signs of the stirrings of memories but there appeared to be none. There was, as far as she could tell, no apparent anxiety to mirror Lydia’s own. Throughout the gruelling cart ride to the coast, the boat voyage hopping from Samothrace to Thassos and onwards to Neapolis, Ruth was her usual relaxed self; poised on the brink of this new adventure as if it were the most exciting thing that had ever happened to her. Lydia looked at Ruth again now, but all she saw was gentle inquisitive concern for Lydia’s welfare, nothing more.

‘You’ll be afraid that what happened back then will happen again.’ John’s gruff tones broke into Lydia’s thoughts. It was probably the longest sentence, not connected to the art of dyeing, that Lydia had heard John utter in a long time.

‘Of course you are,’ said Ruth. ‘What we don’t understand is why you won’t talk about it.’

Lydia looked at her, astonished. She opened her mouth to speak a couple of times, but hesitated. At last she spoke in a tumble of words: ‘I thought you didn’t know. I didn’t want to worry you. I didn’t know how. I was so ashamed . . .’ She tailed off into silence.

‘I was there, of course I know,’ Ruth said. ‘You just never wanted to talk about it, so I talked to Tata instead.’ Although technically no blood relation, Lydia’s father – with a characteristic generosity – had gathered Ruth to his heart when they had reached Thyatira, weary after the long journey from Philippi. So it had seemed natural to everyone when she called him Father. No one could remember when she’d started doing it, it was so obviously the right name for him.

‘So he knew? Did everyone know?’ Lydia said, incredulously, as she attempted to readjust reality in her mind. What she thought a secret so well kept that no one knew of it was apparently a well-known tale that people avoided mentioning to protect her feelings.

‘Well not everyone obviously, but you must have known that people would wonder what had happened to the business in Philippi and why you had arrived unannounced with a young girl they’d never heard of before?’

Lydia closed her eyes as the memory of those first days back at home in Thyatira came flooding back to her. She had been so numb and tired when she had arrived back home that she had simply not wanted to talk to anyone. The few visitors she had seen had, she remembered, tried to ask her what had happened and whether she was all right, but each time she had changed the subject or sat in awkward silence until, eventually, they had given up and gone away. She had always imagined that this meant she had kept her secret; now she began to wonder whether her silence had been more eloquent than any words.

‘Tata tried to talk to you again when we made the plan to come back,’ Ruth went on, ‘but you just wouldn’t talk to him. He is so worried about you. We all are.’

Lydia cast her mind back to the numerous awkward exchanges she had had with her father over the preparations for leaving. Guiltily, she realised that she’d written him off as an old man who was reacting badly to change, when all along he’d seen her panic and had been trying to help. She looked back to Ruth. ‘Why didn’t you say?’

Ruth threw her hands upwards in exasperation. ‘I have been trying to talk to you for ten whole years.’ Travellers, trudging their way along the road weighed down by their heavy burdens, lifted their heads at the sound of her frustration. ‘You just won’t listen; you never listen.’

Normally, Lydia would have been horrified at the thought of the attention they were drawing to themselves. For once, however, she paid no notice to the commotion they were causing. The story she had told herself over the years of a serene closing of the door on everything that had been so difficult, leaving her reputation intact and Ruth blissfully ignorant of all that had taken place, had been snatched from her grasp. It had been replaced instead by a much less flattering tale of denial and self deceit.

Her emotions must have been written clearly on her face because Ruth threw herself into her arms. ‘Dee-dee,’ she reverted to the affectionate name she had first used for Lydia before she became too grown up for such childish terms, ‘don’t worry. None of us want you to worry. I talked it all through with Tata. I’m fine. He’s fine. We just want to make sure that you are too. It is so hard when you shut us out.’

‘But aren’t you even a little bit scared?’ Lydia was struggling to adjust to this new view of events. ‘You’re the reason we had to leave.’

Ruth grinned. Her frustration now vented, she seemed to have reverted to her usual sunny self. ‘Not the entire reason, there was that moment when you stood in the forum shouting at Caius and Julius in the marketplace so vehemently that you were nearly arrested on the spot.’

‘True, that didn’t exactly help.’ Despite the many anxieties jostling her, Lydia couldn’t help smiling at the memory of the time when she had lost all semblance of dignity and shouted as though she was possessed by a spirit. ‘So you remember it? And you’re still not afraid?’

‘I was a little girl, not a baby.’

‘But you were so quiet, you barely said a word afterwards.’

‘Not speaking is different from not remembering. Of course I remember it. Some of it is a little jumbled, but I do remember my old life.’

‘Do you remember us running away?’ Lydia asked.

‘How could I forget?’ said Ruth. ‘I’ve never run so fast or so far since, but surely our departure will be forgotten by now? Alexander has been there all this time tending the business. Surely people will love purple more than they care about something that happened years ago?’

Not for the first time, Lydia pondered Ruth’s youthful confidence. Following a traumatic early childhood and the catastrophic incident that had led to their flight, Ruth had been surrounded by people who loved her unquestioningly, and, nourished by that love, she had blossomed into the self-assured young woman she was today. But was she right? Would people have forgotten? Or were they heading back into the middle of the same storm from which she had fled all those years ago?

Her aching bones swayed along with the lurching cart as it headed northwards along the Via Egnatia, its sturdy wheels scattering hot, midsummer dust over the unfortunate travellers they passed on the way. It was, she realised, the shame that still clung to her, its fumes as noxious as her father’s dyeing workshop in the summer heat. She had called it fear and, while her stomach still lurched at the thought of that turbulent time all those years ago, what she had never acknowledged was the shame she felt. She had been so successful in Philippi. People across the city and beyond, almost despite themselves, looked up to her: a woman on her own in trade who had succeeded against the odds. She had a great reputation. She knew who she was. She had found her place in the world.

It had been her idea to go to Philippi in the first place. Some traders passing through Thyatira had laughed at the prices they asked, joking with each other about the profit they would make when they took their wares to the gullible Romans. People in places like Philippi, they said, would do almost anything for purple. They were, it turned out, entirely right. In Thyatira, where the madder plant grew abundantly and dye was produced in copious quantities, the price for purple was low and profits small, but in Philippi, a Roman colony, where demand for purple was high and purple sellers were rare, there were great profits to be made. At first her father had been reluctant to let her go. They only had each other, he said, and wasn’t that worth more than the profits they would make? But Lydia had set her heart on it and in the end he gave in. The business had grown and grown, and, although she missed her father, her success put all other thoughts out of her mind. There were other sellers of purple, but none so sought after as Lydia. She was a triumph . . . but then she had had to leave, abandoning not just the business but the hard-won admiration she had built up little by little over the years.

Ruth leant over and squeezed her hand. ‘We’ll be fine, Lydia, you’ll see.’

‘You’d better be,’ said John, ‘we’re nearly there.’

And he was right. Through the shimmering haze it was possible to pick out the faintest outline of the city walls.

Chapter 10

Lydia sat waiting, sensing that Artemis would begin again when she was ready. She knew Epaphroditus had gone to see Paul in prison, but beyond that knew very few details of why he had gone or of what had happened next.

After a few moments, Artemis began speaking again. ‘It all started to go wrong before he went really. We’d heard about what happened to Paul in Jerusalem and how he was being sent by ship to Rome.’

Lydia nodded; they’d heard about that in Thyatira too. Timothy and Silvanus sent letters from time to time telling people news of Paul and what he had been doing. They would be copied and passed from hand to hand around all the churches he’d founded, and, as in the case of Thyatira, those he hadn’t founded too. They’d been horrified to hear of Paul’s arrest; horrified again when he was sent to Rome, despite Timothy’s reassurance that it was what Paul had planned; terrified while they waited for what felt like endless months for news of his arrival; relieved to hear he had arrived safely in Rome, but, at the same time, worried not just for him, but for themselves too. What would happen to them all if Paul was condemned to death? What if, when Paul saw the emperor, he declared faith in Jesus Christ to be against Rome and Roman values? What would they do then? Back in Thyatira they’d talked about it for hours. It wasn’t as though any of them, other than Lydia, had ever met Paul, but he represented something even to them, and they weren’t sure what they would do without him.

‘We were so cross with Paul,’ Artemis continued. ‘Timothy passed through one day, after Paul had been arrested. He told us not to worry; going to Rome was what Paul had wanted all along. He had taken the good news of Jesus to the ends of the earth – and had plans of even going further, to Spain, once he’d been to Rome – and now was taking it to the centre of the known world. Timothy was usually so level-headed and calm, but even his eyes sparkled as he told us about how Paul was going to speak to the emperor to tell him the good news of Jesus. We were gathered together that day, the overseers and deacons from across the whole city, to talk to Timothy and hear the news. I remember Euodia exploding with rage at Paul’s selfishness, gambling with the safety of us all by going to the heart of power for what she saw as a vanity project. What would happen to us all if it went wrong? What if the emperor Nero took against us? What would happen then? We’d heard stories about Nero, about his mood swings and unpredictability. What if followers of the Way drew his attention? What would happen to us then?

‘Euodia gave a long and impassioned speech about the importance of us distancing ourselves from Paul. Putting space between us and him, and then if anything happened, people would know we were different. “We aren’t, though, are we?” Epaphroditus had said. “We aren’t different. We follow the same Jesus Christ as Paul. And even if we were, the Romans wouldn’t see it. Surely you remember how they expelled the Jews from Rome because of arguments about Christ? If they can’t tell a Jew from a follower of the Way, how will they tell the difference between Paul and us?” He then scolded us all for our selfishness. He’d grown by then, from my hesitant little brother into a tower of integrity and justice. He was still his sweet gentle self, but he fought for what he thought was right with single-mindedness and passion. He was, he said, horrified by our self-centredness and negligence. Paul was in prison, for proclaiming the Gospel, and all we could think about was whether we would suffer as a result. He seemed to grow a hand’s breadth or so in his indignation,’ Artemis recalled, ‘and we all squirmed in the heat of his fury . . . well almost all of us did. Euodia didn’t. She was adamant that Paul had let his pride run away with him and refused to listen to Epaphroditus’s impassioned pleas.

‘Then Syntyche stepped in. Her gentle presence usually calmed the most vicious of arguments, but not this time. Euodia looked really frightened. She knew what happened when you became an enemy of the Romans, and she was convinced that what she called Paul’s vanity project would bring the full wrath of Rome down on us all. She was, she declared, done with Paul. He would get no more help from us in Philippi . . . ever. Timothy left that day empty-handed, a little deflated and chastened. He used all the persuasive powers available to him – and Timothy could be very persuasive when he wanted – but it was to no avail. Euodia and a few others were intractable, and no amount of coaxing would get them to change their view.

‘The next we heard of Paul was when he had arrived in Rome and was set up in a small house near the Pantheon, along with the solider that was looking after him. Epaphroditus and Syntyche worried about him constantly: concerned that he had to take care of himself in a strange city where he couldn’t go out to meet people; anxious that he would grow weak and tired, kept inside without access to fresh air and good food; troubled at the thought of him running out of money. They wore away people’s reluctance with their persistence, visiting person after person until they had gathered a sizeable gift ready to send to Paul in Rome. Euodia never came around and refused to have anything to do with the scheme, but almost everyone else did, and before long we waved Epaphroditus off on his long winter journey from Philippi to Rome.

‘I couldn’t help thinking,’ Artemis said, ‘as I waved him off, that if he’d gone when Timothy had first visited, he would have been leaving in June and could have gone by ship in half the time. The delays and endless arguments meant that by the time Epaphroditus was finally ready to leave it was January and far too dangerous to navigate the seas. So he trudged off to Rome down the Via Egnatia, the money bound to his body. In April, we received a letter telling us that he’d safely arrived. After a couple of months, we got another letter. Then just before you got here I got a note from Timothy telling me that Epaphroditus was seriously ill and might not survive. And since then,’ Artemis’ voice wavered, ‘nothing. Day after day I have waited for news, and day after day there is nothing. It’s the waiting . . . it’s never ending. He might already be dead. I tell myself I’d know if he died, but he’s so far away, maybe I wouldn’t.’ She tailed off, her heartache written clearly all over her face.

Lydia reached for words, but found none that would fit. She wanted to tell Artemis that everything would be all right, but had to admit she had no idea whether it would be. She wanted to reassure her that Epaphroditus was alive and well, but didn’t know if he was. She wanted to comfort Artemis with the knowledge that whatever happened she would get through this, but had to admit she had no idea if that were true. In the end she gave up reaching for words and sat quietly next to Artemis, grasping Artemis’ hand in her own. She felt useless, frustrated by her own inarticulacy. After a long period, Artemis heaved a shaky sigh and turned to Lydia to thank her.

‘But I did nothing,’ Lydia protested.

‘You did everything,’ said Artemis. ‘I needed to know I was not alone. Now I do.’

She patted Lydia’s hand and got up to return to the kitchen, looking visibly lighter in spirit. Lydia shook her head in bemusement, glad to have helped, but unable to work out what she had done. A moment later, Ruth burst into the atrium, her eyes sparkling. Lydia’s gaze flicked instinctively towards the front of the house where the two shops were located – if she and Ruth were here, who was in the shop?

Ruth catching and correctly interpreting her eye movement said, ‘Don’t worry, the boys are in there. Rufus is telling a Roman gentleman the story of Hercules’ dog and the discovery of purple.’

Lydia was only mildly reassured. Rufus’s love of storytelling, combined with his equal fascination for gore, loved to turn the gentle story about the hero Hercules, who was strolling along the beach near Tyre one day with his dog, which ate a murex shellfish, turning its saliva purple, into a horror story of the dog foaming at the mouth with red drool before dropping down nearly dead at Hercules’ feet. Lydia acknowledged, however, that the shops were in safe hands, and that she could wait long enough to discover what had made Ruth’s eyes sparkle so brightly before rescuing the Roman gentleman in question.

‘Tell me a story,’ she said, slipping into the well-worn question from Ruth’s childhood. Ruth had started it when they had first arrived back in Thyatira and had often been left at home while Lydia went to see old friends and business acquaintances. Thirsty for knowledge of Lydia’s life she would ask her what she had been doing and when she answered in a simple sentence would object. ‘No, a story,’ she would say, demanding that Lydia take time to give shape and texture to her tale, to describe the people she had met and the interactions she had had. It didn’t come naturally to Lydia, but over time she grew to appreciate Ruth’s insistence. She would pay more attention to her surroundings and store up the treasure of a small detail here or turn of phrase there that would entrance Ruth later in the telling.

She was, therefore, doubly astounded when Ruth said simply, ‘I’ve been chatting to Caius.’ It took her a moment to form her words, and even then all she could squeeze out was ‘No, a story’.

Ruth leant over and grasped her hand. ‘It’s all right, Dee-dee, you don’t need to worry, he’s all right, I’m all right.’ But then she relented and started at the beginning. Lydia, happily absorbed in her work in the shops, and feeling awkward about her relationship with Clement, had not noticed that Caius had begun working in Clement’s shop next door. He was, Ruth reported, a natural. His love of performance and of fancy things meant he could find exactly the right brooch or hairpin for the fastidious Roman ladies who dropped in on the way out of Lydia’s shop. He had become quite a draw, and no one, other than Clement, Lydia and Ruth, appeared to have connected him with the Caius who had left the city in shame so many years before. Lydia hadn’t noticed his regular appearances in the shop, but Ruth had. Her sharp eyes had observed his arrival day after day, until one day she had decided to go and see him.

‘Why didn’t you say anything?’ Lydia exclaimed. ‘I would have come too.’

‘That wouldn’t have worked. You would have glowered at him and he would have got defensive and I would have said nothing.’

Lydia had to acknowledge that this was probably true. One of the passages from the Scripture that she’d always loved was the prophet Hosea talking about God being like a mother bear robbed of her cubs. It summed up perfectly her emotions towards Ruth. Whenever she thought of the thoughtless, selfish way that Caius and Julius had used and discarded Ruth, she could easily imagine rearing up on her hind legs, a clawed hand ready to rip them to shreds.

‘But I was always safe. You’ve taught me above all to look after myself and be safe.’

Lydia smiled, despite herself. After what had happened to Ruth as a child, she worried that she would become prey for other unscrupulous men looking to take advantage of a young girl, so she had spent hours schooling her in what to look out for, how to be safe in a savage and uncaring world.

‘First I talked it over with Alexandra, then with Clement, and today, when the time was right, I talked to Caius. Alexandra and Clement never left me alone with him, I was always safe. Dee-dee, I’m so glad I did.’ Ruth turned to her, her eyes sparkling again. ‘I told him how he’d made me feel. I told him the effect his behaviour had had on me. I don’t think he’d ever thought about it. He and Julius had been so caught up in the money and the excitement, they’d forgotten that I was a person, not a “thing”. We talked for hours. I think he understands. He asked me to forgive him. I don’t know if I can. I told him that I’d try. So I will . . . I will try. It might take some time though.’ Ruth paused and looked thoughtful, then reached over and took Lydia’s hand in hers. ‘I’d like you to try too.’

Lydia opened and shut her mouth a few times. This was not something she had been expecting, and she had no idea how to respond. She’d never thought of Caius as someone to forgive. He was the person responsible for driving both her and Ruth from Philippi all those years ago. He was someone from whom she needed to protect Ruth. He was selfish and arrogant. He was thoughtless and careless. He was not someone she had ever thought of as a person worthy of forgiveness.

‘Will you try?’ Ruth asked.

Lydia nodded reluctantly. It was all she was able to do.

Ruth jumped up and ran next door before Lydia had time to express any of the doubts that were already flooding her mind. She followed her to the street door, her mind a tangle of uncertainty and fear.

Chapter 11

As Lydia stood at the door waiting for Ruth’s return, her attention was caught by the man in the shop, who was still talking to Rufus, Marcus and Tertius. She looked over, wondering whether their tale of Hercules and his dog was proving interminable. It was not. In fact, he was regaling them with a story, and on each of their faces was a look of pure delight. It was the look they always had when a story, well told, was unfolded expertly before them.

The man had a rugged, sun-beaten face. Lydia thought he might be around sixty, but he could have been younger. His bearing indicated that he was a veteran of the Roman army. There were so many in Philippi, Lydia had learnt to identify them at a single glance. In her experience, years marching in the sun combined with what they had seen and done as soldiers often meant that they looked considerably older than they were. Not only that, but their years in the army made them tough and argumentative. As a rule, Lydia feared their presence in her shop. All too often, frightened by their aggressive confidence, she would end up selling them what they wanted for less than it was worth.

This veteran seemed different. Rather than driving a hard bargain and leaving swiftly, he was sitting down, apparently enjoying the boys’ company, his face alight as he was describing something to them. Their faces mirrored his every expression. Even the naturally reticent Tertius seemed to be joining in. They turned as they became aware of Lydia’s presence in the doorway to the shop. The veteran rose politely to his feet and came forward to greet her. His name, he said, was Manius, and he had heard in the city that she might be able to tell him more about a ‘Jesus of Nazareth’. Lydia started in alarm. Romans – especially ex-soldiers such as this man – were often hostile to followers of the Way. People like her were labelled ‘un-Roman’. It suddenly dawned. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...