1

CHAGRIN FALLS, OHIO

The white envelope that drops through our mail slot is the size and heft of a magazine. Or a music book of piano sonatas, which have often found their way through that same slot. But I know it’s not either this time. I swoop down on it as the metal flap slaps shut. A bass drum has replaced my chest, pounding out my heartbeats to a metronome on overdrive.

“Mom! It’s here!” I yell.

At this weight, it can’t be a rejection letter, can it? No. No, it can’t. But months of anticipating, dreading its arrival . . . and I can’t muster the courage to open the package just yet. I run my thumb over the gold embossed monogram that stands for Apollo Summer Youth Symphony.

Old-fashioned, elegant. You can practically smell the generations of excellence—centuries of tradition—wafting off the heavy paper stock.

Okay, go time. “Please, please, please, please, please!” I whisper a fervent prayer—and rip it open.

Mom hurries into the foyer from the kitchen, drying her hands on her blue-apple-print apron.

“Dear Ms. Wong, we are delighted—Oh my God! I’m in!” I fling my arms around Mom’s frail neck, almost knocking her over—and sending her bifocals clattering to the floor. “I got in! I got in!”

I recover her glasses, which she returns to the tip of her nose. She reads, “We are delighted to admit you to this year’s class. Oh, honey. You worked so hard for this!” Her brown eyes shine as she wraps her arms around me, then pulls back to look me in the eyes. “You deserve this, Pearl. I’m so proud of you.”

I can barely believe it. Two months ago, nine judges listened to me play my heart out on a Steinway piano in the Hunter College auditorium, and at least six of them decided my music was good enough to make the cut. At least six of them were pleased.

“They only take a hundred kids from the entire country.” I scan the roster of names that form a pair of elegant columns on their own page. With a thrill, I recognize a few heavy hitters from performances I’ve played in over the years.

“I’m the only pianist, which means . . .” I page through to my repertoire, the songs I’m assigned to play for the concert series at the summer’s end. “I’m playing the Mozart Concerto in D Minor!” His darker concerto, written later in his tragically short life. It’s incredible—the contrast of light, sweet notes with the darker raging ones, bound together into three movements, thirty minutes in length. And I’ll play it accompanied by the full symphonic orchestra, before an auditorium of 2,738 seats at Lincoln Center in New York!

My head is fogging over. Pink clouds of happiness obscure any rational thought. There are too many words on the pages I’m gripping. Big ones that in this moment I’m too ecstatic to comprehend. I shove the papers into Mom’s hands.

“Read the rest,” I beg. “Tell me if this is real.”

She scans the pages while I storm up and down the living room. I can’t focus on anything. Calm down. Take notice of the things around you. Breathe.

I inhale, then a loooong exhale. Okay. Blue curtains, blue couches, blue carpet. God, everything is blue. How did I not notice that before? I pause before Mom’s collection of brass miniatures—a piano, a grandfather clock, an iron. I pick up a tiny park bench, with three words engraved on its backrest: thankful grateful blessed.

Yes. I squeeze it in my hand. Yes.

“I peeled you a grapefruit!” Mom says, her eyes still on the papers. “Eat some.”

Food always comes first in our family. Feeding me semi-nonstop is her equivalent of love you, kiddo. I set down the miniature and head for the kitchen, where Mom’s big blue bowl of citrus sits on the counter. But I can’t eat. A concerto. Most piano pieces are

written for solo performance, which is one of the reasons it can be such a lonely instrument to dedicate your life to. But a concerto. It’s a piano solo with the entire symphonic orchestra in a semicircle behind you, playing along—a hundred strings, woodwinds, brass, and percussion. It’s the opportunity of a lifetime! One my dad helped me work toward and cheered me on to so faithfully, until he passed away two years ago.

Mom is opening a small box left on our doorstep as I return. She removes a glass globe on a velvet stand. Inside it floats a tiny grand piano and golden words Apollo Summer Youth Symphony. I weigh it in my hands.

“It’s beautiful,” I breathe. “And, oh my gosh, I’ll be in New York! I’ll get to spend time with Ever!” My older sister, who works as a choreographer for the New York City Ballet. She’s twenty-four to my seventeen. We’re super close, but since she left home for college, we haven’t had nearly as much time together as I wish we did. And now, we’ll have the whole summer!

Mom waves the papers. “Everyone is performing three times during the festival week in August. You’re playing a solo, a piano-violin duo, and . . .” She starts to sob uncontrollably.

“Mom, what’s wrong?” I grip her arm and hand her a tissue from the box. “You’re not doing that thing where you get over-invested and my successes become yours, are you?” I tease her gently.

She dashes her hand over her eyes. “Your dad would be so proud of you.”

My throat aches. Yes. He was the one who discovered Apollo online a few years ago: What a fantastic program. If you can get in, Pearl. It will change your life! I wish he were here to celebrate with us, pushing his thick glasses closer to his face and squeezing my hand in his worn ones. We’ve had happy moments since we lost him, but the happy is always constricted by the vacuum he left behind.

Mom sniffs noisily. “I was remembering, just this morning, that time we were detained at the Canadian border trying to come back home here. You were only a baby. The way they looked at us. So suspicious. I remember your father and I saying then, ‘My God, this country will never accept us.’” She clasps the Apollo papers to her heart. “And now, I know we were wrong. They have accepted us. Thanks to you, and your sister, and all your hard work. I just wish he knew.”

“Oh, Mom.” I hug her tight, tucking her graying head under my chin. She and Dad moved to the United States over twenty-five years ago. All these years later, I didn’t know she felt this way about my music performances. Maybe Dad did, too. In this moment, I feel the same, looking at the official gold emblem on the page. Apollo Summer Youth Symphony. This is legitimacy.

After so many years of standing on the outside, gazing longingly in, I’ve been invited to the club.

“Congratulations, Pearl,” my manager, Julie Winslow, says on FaceTime later that day. Her dark-blond hair is twisted into her usual chignon, and her ice-blue eyes, framed by long mascaraed lashes, crinkle with her broad smile. “You earned this. I’m so proud of

you.”

“Thank you,” I say. Julie signed me a few years ago and walks on water; praise from her is hard-won. “I have one solo song to decide on. I thought, maybe—”

I chew on my bottom lip, unsure whether to continue. I recently ran into a beautiful and complex modern piece on YouTube by a composer no one’s ever heard of. Chaotic but organized rhythms that didn’t restrict themselves to the eighty-eight keys but also came from drumming on the piano cover and even plucking the strings inside. But would Julie go for it?

“Play the Rachmaninoff,” Julie says. “Incredibly technically difficult. It shows off your abilities to the fullest. The reviewers will take note. I’ll arrange for the accompanying pianist.”

I exhale. It’s the composer’s hardest piece, going from a trickle of notes to a finger-twisting torrent that plumbs the depths of human emotion. One of Dad’s favorites, and I do love it, too. I push down the whisper of disappointment—drumming on a piano would be gimmicky anyway. I’m grateful for her guidance in a world I’m learning to navigate.

“Sounds perfect, Julie.” I set Apollo’s glass globe on my piano where I can see it as I play. “I’ll get to work.”

I’ve been hooked on music since I was four and Dad played me Leonard Bernstein’s recording of Peter and the Wolf by Prokofiev, with all the ways animals could be imitated by strings and woodwinds. Then there was Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute; the very idea was delicious. Songs are how I experience the world: they lure me into secret gardens and stormy rivers. Piano was also my bonding time with Dad, who sat with me, first to help me with my dyslexia, which made it hard to read the music, and later, to keep me company. He was always positive, even when my fingers wouldn’t cooperate with my ears. Even now, every time I sit down at the piano, I still imagine his gentle, encouraging presence beside me. You can do this, Pearl. Piano doubles as my way of staying close to him, and I’m so thankful I have it.

Mom and I make the half-hour trip to Cleveland to splurge on an updated headshot with a professional photographer. We’re used to spending hours in the car together driving to my music events. Probably why she and I have a closer relationship than she and Ever do.

Ever had it rough—she was the one who broke the mold. She paved the way for me by choosing dance as a profession. At the time, my parents thought the only viable career path was medical school, until she showed them the trail she was blazing for herself.

And after Dad passed away, for better or worse, Mom lost a lot of her will to fight us.

Pierre, our photographer, has a head full of wild brown curls and a studio bursting with Renaissance paintings. I feel the Apollo aura shining on me as he positions me standing and seated. He tugs my purple beret over my left brow for a dramatic effect and smooths

my long black hair down my back.

“Magnifique!” he says. “Vous êtes très belle. Very beautiful.”

“Take one of my mom,” I say, tugging at her arm.

“Oh no.” Mom blushes, something I’ve never seen her do, and runs a hand through the graying leaves of her hair. “I’m too old for photos.”

“No you’re not.” I guide her to the backdrop. “The red background is perfect with your skin tone. And it’s just for us anyway.”

She protests, but when Pierre lifts his camera, she smiles.

Afterward, we sip sparkling water and pore over our glossy images on his screen. “You look so pretty,” I say to Mom.

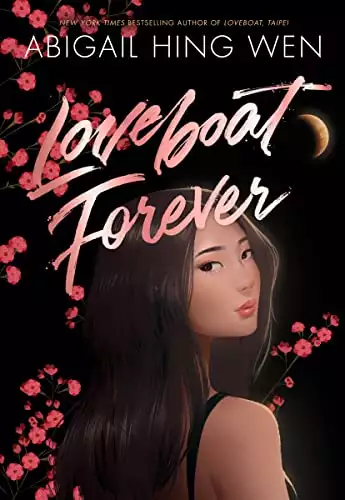

“It turned out okay, didn’t it?” she says, embarrassed but obviously pleased. She flips to the next image of me: gazing over my shoulder and backdropped by plum blossoms at night. “I like your smile.”

My beret is like a cloud floating over my head. I fell in love with berets in middle school French class, and they’ve sort of become my signature piece on social media. Beneath its soft fabric, my black hair tumbles down my shoulders, framing glowing cheeks and mysterious dark eyes. My body, which has always been heavier than I’d like, looks surprisingly good in my black concert dress.

“I look like a movie star,” I say, dazed.

“Maybe you will be one someday. A star!” Mom says, and I just laugh.

A few days later, I email my glammed-up photo to Maude Tanner, the Apollo administrator, who I envision as a grandmotherly white-haired woman.

“Thank you, Pearl!” she responds immediately. “We look forward to seeing you soon.”

I feel a thrill deep inside me.

Mom contacts the World Journal, the largest Chinese language newspaper in North America. They profiled my debut at Carnegie Hall when I was thirteen, all of which sounds more impressive than it actually is these days. They tell Mom they’re interested in doing a piece on me attending Apollo, so she arranges for an interview the day before I leave.

Two weeks before the program kicks off, Apollo sends me an update: their website for the summer program is live.

“Mom, it’s up!” I rush into the living room, and Mom joins me on the couch. We scroll through on my laptop: The daily rehearsal schedule is packed but exciting. The final performances, including solos and ensembles in smaller halls, are all day Saturday, August 11. Mom will fly in from Ohio, and it will be a chance for her to see Ever, which is always at the forefront of her thoughts.

Last but not least, we scroll through the musicians, savoring them. It’s a virtual hall of fame, with classes from the 1980s to present day: eighty musicians between the ages of fifteen and eighteen, hailing from Hawaii to Maine and Seattle to Boston. Marie Smit

draws her bow across her violin strings. Geoff Pavloski plays a marimba, two mallets gripped in each hand.

At the end of the alphabet, I come to my airbrushed headshot: Pearl Wong, concert pianist.

“I’m not dreaming,” I say. I scan the bio. Words leap out at me. Beautiful ones: “Known for her effortlessly expressive playing, Pearl Wong has a command of the piano well beyond her youthful years. She plays with her entire body and soul, bringing audiences with her. Um, wow. Are they talking about me?”

“He’s very nice-looking. Good hair.” Mom points to a Korean American flutist. “There are only three Asians,” she notes.

“I’m Asian American,” I correct her. “They might be, too.” But she’s right about the numbers. Besides the cute flutist, there’s an Indian American cellist . . . and me. I click on my name and arrive at a page with my repertoire:

|

L. van Beethoven

1770–1827

|

Piano and Violin Sonata no. 9, op. 14, no. 1

|

|

W. A. Mozart

1756–1791

|

Piano Concerto no. 20 in D Minor, K. 466 (with orchestra)

|

|

S. Rachmaninoff

1873–1943

|

Piano Concerto no. 3 in D Minor, op. 30 (with piano orchestral reduction)

|

I close my laptop. It’s real. Dad, I’m really in. My throat swells. I can barely choke out the big truth in all of this: “I’m so lucky they took me.”

I learn everyone’s names, faces, and instruments by heart. Not because Julie is constantly telling me it’s important to network, but because they’re about to be my new friends. The rest of the time, I practice. All our individual prep is to be completed before we arrive, so our days can be spent practicing together for our performances.

For hours at my piano, I run my fingers over the ivory keys, mastering the concerto page by page. Ever once asked me if I’d rather have an exquisite, emotive painting with a scratch down its middle or a flawless painting that meant nothing to me. The answer was clear: focus on the beauty of the sound instead of on perfection. Of course, I still do have to get the notes right. I execute the cascading runs, pushing the tempo but also the emotion. Again. Again. Again, again, again until I’ve brought my hands in line with what my ear tells me the music should sound like.

Most professional musicians play eight-plus hours a day, but I usually cap out at six. It’s not as impossible to fit the time in as it sounds: I wake up with the sun and play two hours before breakfast. After

school, I get a snack, then sit down for another two hours before dinner with Mom. I dash off my homework, then play another couple of hours before bedtime.

I know it’s not a normal teenager’s life. It doesn’t leave much time for friends and definitely not romantic relationships. Friday nights are for practicing. Saturday’s are at the Cleveland Institute of Music: private piano lessons, theory classes, and choir, which teaches me to be a part of an ensemble and overall musicality. I travel six times a year for performances—most recently, Philadelphia, Atlanta, Denver, Chicago, San Jose, and London.

Sometimes, when the kids at school are talking about weekend plans—movie theater, road trip, shopping, dates—a part of me wishes I could join them. But the music demands to be what it deserves to be. And so my fingers keep tackling the keys. I imagine Dad’s encouragements. “That phrase! I felt it right here,” he’d say, closing his eyes and touching his fingertips to his heart. I wish he could hear my debut concerto performance in Manhattan. I wish I could see his gently lined face light up with pride.

Thank you for keeping faith, Dad. I miss you. So much.

My phone chimes with a text from Julie, a blue bubble with white type: How’s your Apollo TikTok coming?

I groan and slip off my piano bench. Julie has me post twice a week to “keep the algorithms fresh,” all part of the overall plan to build my profile as a public artist and be relevant to my generation. Julie’s biggest clients have huge followings on TikTok, and I know I’m lucky to have her advising me.

But there’s nothing more discouraging than spending hours making one of those short silly videos, only to have it viewed by, like, five people. Still, I’ve posted faithfully for the past year, and my posts have steadily climbed to about two thousand to ten thousand views, depending on the whims of some secret programming I haven’t cracked yet.

Now, fortunately, I’ve got something good to post about.

Haven’t made it yet, I confess. But it’s coming.

Post a selfie of you at the piano. You’re excited to be joining the crew. Your classmates are already posting.

Nudge, nudge. That’s Julie.

You can see their samples online.

I’m on it, I promise.

The cool thing about the TikTok icon is it’s actually an eighth note. Endearing. I open my app and search for posts tagging @Apollo: a violinist from Los Angeles with her hair in a long blond ponytail. An oboe player from upstate New York.

I get up to change my clothes for a selfie, and an envelope falls from the overstuffed storage compartment of my piano bench. It’s labeled with the Chien Tan logo—an invitation to a six-week summer program in Taipei to learn language and culture. I get one every year, offering an all-expenses paid scholarship. They like me for my musical accomplishments, and of course, my sister attended six years ago, when she was a year older than I am now. She was popular there, despite the early gray hair some of her (ahem) adventures gave Mom and Dad.

I touch the logo. The scholarship is flattering, and I’ve always secretly wanted to go. Not for the cultural part—but the transformation. Chien Tan has a secret identity: Loveboat. That’s what the students call it. Parents don’t know it’s a huge party with hookups galore.

Ever came back with the incomparable Rick Woo as a boyfriend and a boatload of courage. That’s when she dropped out of her premed program to pursue dancing and changed our whole family. Without Ever—without Loveboat—who knows what kind of path my parents might have pushed me toward. A business degree? A career in law? Nothing wrong with either—they’re just not for me. I’d much rather fly—the clear, crisp notes swirling around me, and my hands soaring over the keys.

“What’s that?” Mom asks. She’s come in with a broom and black trash bag to clean out the hallway closet for the first time in ten years.

“Mom, Ever’s not going to look in there.” I smile. Ever’s coming home from New York tonight for a weekend visit, and Mom’s gone into extreme nesting mode. I show her the creased letter, dated a few months ago. “It’s a Chien Tan invitation. All expenses paid, plane ticket and everything.”

Just as I expected, she frowns. “Again? Every year they hound you. Don’t they know by now the answer is no? I should call them and tell them to stop sending you those ridiculous invitations.”

I smile. “They’re not so bad, Mom.”

Mom just harumphs and opens the closet door.

In my bedroom, I pull on my slim brown dress with the cowl neckline. I prefer bright colors, but Julie is adamant that my outfit should never draw attention, only my music. But she’s okay with me wearing my berets for social media, so I adjust my orange one over my black hair.

When I return to the living room, Mom is tossing old winter coats from the closet to the floor. I adjust the Apollo glass globe on the piano, then sit on the bench at an angle that lets my face catch sunlight from the window. I pop my iPhone into the phone stand Julie had me invest in for just this purpose and snap photos of me looking down at my keys, and a few looking straight into the camera.

“Almost done!” Mom says triumphantly. She dashes her arm over her sweaty hairline and plops a wide, conical straw hat onto the coffee table, beside a pile of gloves and scarves I haven’t worn since middle school.

“Where did we get this?” I ask, picking up the hat. I’ve seen it on the closet shelf for years. It looks Chinese, old school, with a cool woven pattern that makes me think of the rhythms of a song. It’s lightweight, with a circumference like a very large plate. Perfect for keeping off the rain.

“I don’t remember,” she says, tugging at a stubborn scarf.

“It’s cute.” I don’t usually wear anything ethnic, not since I was a little girl taking Chinese dance classes. But this one’s fun. I swap my beret out for it and snap a few more selfies, seated and standing. I like the way it frames my face, and its roundness

complements the rectangular piano background.

“Mom, what do you think?” I show her the best four photos, though I’m not sure she knows what TikTok is, or how multiple photos can be turned into a video collage.

She laughs. “So cute. East meets West.”

I assemble the photos for a video collage that makes me pop up in different poses around my piano, ending with my hands coyly tilting the hat’s brim over my face. Pierre would approve. I text the finished video to Julie, who reviews all my posts before they go live. She usually has comments—make it more personal, show more of me instead of inanimate objects. Things like that. I draft a sample caption: Can’t wait to join the cohort @Apollo in just a few weeks.

Add “of amazing musicians” after “cohort,” Julie writes back. Thanks for getting this done.

I upload the video onto TikTok, add a pop song, then shut off my phone and head back to my piano.

Morning sunlight pierces my eyes. Mozart’s Magic Flute fades with a blurred dream, punctuated by a rap on my door.

“Come in?” I mumble.

Ever pops in, holding her phone out toward me. Her sleek black hair frames that oval face tapering gently to her chin. That face I know better than my own, that makes everything here feel complete.

“Pearl—”

“You’re home!” I fly at her and squeeze her in a hug, swinging sideways with a rush of lightheadedness. She flew in last night after I was already asleep, and now she’s in her old high school pajamas with fluffy blue bunnies hopping everywhere. Just like old times.

But she looks terrible, with dark circles under her eyes and a distressed expression.

“Is everything okay?” I ask. “Is it Rick? I know the breakup’s been hard. Do you want to—”

“It’s not that. It’s your TikTok. It’s blowing up.”

“Well, that’s great! I’m really bad at getting any engagement there. It’s so tricky, and I—”

“Pearl! Listen to me!” Ever’s delicate brows furrow over her eyes. Her voice is clipped and urgent, and she thrusts my phone into my hand. “This is bad. You need to delete your post right now.” ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved