- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

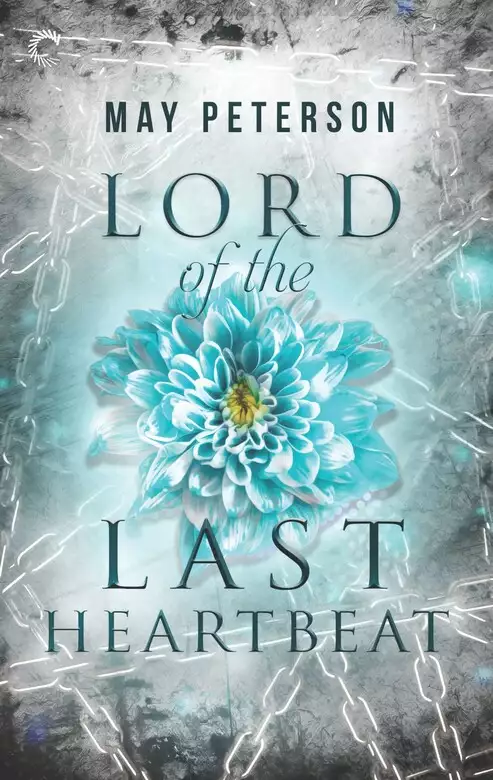

Synopsis

Stop me. Please.

Three words scrawled in blood red wine. A note furtively passed into the hand of a handsome stranger. Only death can free Mio from his mother’s political schemes. He’s put his trust in the enigmatic Rhodry—an immortal moon soul with the power of the bear spirit—to put an end to it all.

But Rhodry cannot bring himself to kill Mio, whose spellbinding voice has the power to expose secrets from the darkest recesses of the heart and mind. Nor can he deny his attraction to the fair young sorcerer. So he spirits Mio away to his home, the only place he can keep him safe—if the curse that besieges the estate doesn’t destroy them both first.

In a world teeming with mages, ghosts and dark secrets, love blooms between the unlikely pair. But if they are to be strong enough to overcome the evil that draws ever nearer, Mio and Rhodry must first accept a happiness neither ever expected to find.

One-click with confidence. This title is part of the Carina Press Romance Promise: all the romance you’re looking for with an HEA/HFN. It’s a promise!

This book is approximately 94,000 words

Release date: September 2, 2019

Publisher: Carina Press

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Lord of the Last Heartbeat

May Peterson

Chapter One

MIO

When I was nine, Mamma took me to the bay and showed me how to crack oysters.

She spotted the oysters as magically as she spotted secrets, her red witch’s eye a gleaming carbuncle in the sun. I only found two by myself. Her hair covered her face like a surgical veil as she slid her knife between the glistening halves.

I was such a little speck of a thing—and Mamma so convincing in her role of carefree Portian maiden—that no one thought much of us there, shin deep in the brine, laughing and splashing for oysters. Even in that postwar haze when families still foraged under the docks for food, a woman playing in the sand with her son wasn’t anything to worry about.

She showed me the muscle that held the shells together, and how the oysters would fight to keep from being opened, violated, their hearts taken out. She explained with a silken calm how it was simply a matter of breaking their resistance.

“Every heart, everything that moves,” she said, “will resist. Feel where the resistance is strongest and—” Snap, the shell opened. “Be precise about it.”

With knife in hand, I trembled to open my little shell. Oyster meat was tastier and softer than almost any other kind, but I couldn’t do it. I wiped a tear away so she wouldn’t see.

But she did see, and took my hand. “Never fear.” With a little shove, she guided my fingers, and cut the muscle.

I gasped. Inside the shell rolled a pearl. A spot of sea shine—it looked like it would pop if I touched it.

Mamma opened my palm and dropped the pearl onto it. “Now you understand why they resist.”

I wanted to ask if the oysters could feel pain, but her face was so wise and sad that I dared not.

She made me hide the pearl in my mouth, under my tongue. Anything else we found in the bay we could keep, though the best finds had to be paid for, but pearls went to the Pescatores, all pockets and hands checked when one l eft the sand. This theft was one more way Mamma showed her lack of fear of the other families. The Pescatores meant nothing to Casa Gianbellicci.

Pescatore’s eldest daughter leaned at the boardwalk exit, beaming at us. “Find anything good?” A toll master’s inquiry, wrapped in warm curiosity.

“Just more oysters than I could eat by myself. Not a better lunch under heaven.” Mamma winked her scarlet

The girl nodded, slowly, and cast her gaze around. Checking for bulges, Mamma would explain later, suspicious lines under clothing. She put her wide hand on my head and ruffled my hair. I shuddered. “What a cute little girl you have! What’s her name?”

I had been a girl before, for some of Mamma’s ruses, young and small enough to slip into the role. Yet with her touch on me, feeling the role close around me, my whole body went as stiff as the muscles of that oyster.

“Aw, thank you. It’s Mia.”

Mia. Mio. Mine.

The pearl felt huge and heavy under my tongue, like a mound of sand. My tongue convulsed by reflex.

And I swallowed the pearl.

Once we’d passed the girl, on the street, Mamma asked to see the pearl. Mustering my courage, I told her what had happened to it.

She looked so shocked I was sure she was going to scold me. But then her face lit up and she smiled more broadly than I could remember, as though I had surprised her in a way she hadn’t thought possible.

“Ah, well.” She shrugged. On the way home, she stole me a lemon gelato.

Looking back, I was never sure if I’d failed or succeeded. I imagined this to all be some arcane witch’s lesson. But it was far simpler. That day at the bay had just been practical education. A master training her new pupil.

On the night of the first new moon of my twenty-first year, she said it was time to go pearl hunting.

There was no way I would pass for a footman.

I matched the real servants drifting in flotillas with their trays down to their minute nacre buttons and oiled hair. I had even spent ten minutes training to stand like them while Tibario held a finger in front of my eyes. But their hands didn’t shiver, nor their glasses spill as they walked. And I was the only one hiding by the shrubs.

Not that it was a very good hiding place. I stepped back under the arms of the trees, woven with calla lilies stained red to the roots. Delicate reflective coins were strung from the trees, setting the branches sparkling. I could almost hear the tinkle of the golden curse chains, binding the ghosts of monks who still decorated this courtyard for festival nights. The watercolor glow yielded no shadow for cover.

The noise of the crowd made me want to disappear, leaving nothing behind but the tulip-colored velour. Tibario had gone off, hunting the priest whose heart was our oyster; I preferred to hunt in spirit.

Fidgeting with my collar, I stepped back onto the grass. But a man’s grunt told me that I’d stepped on a foot.

The man snarled and I squeaked in perfect unison. Before I could apologize, a hot hand grasped my free wrist, roughly turning me.

“Ho, there, trying to trample me?”

His breath was so thick with drink it made me gasp. The man who held me seemed broader than the trees but not nearly as decorated.

“I—I beg your pardon, signor,” I stammered. My shaking set the glasses a-tinkle. “I did not see you.”

He let go abruptly, and I almost fell back. I kept hold of the tray while managing a bow. The man laughed hoarsely, then coughed. Perhaps he’d been vomiting his festivities up into the fountain. Nice surprise for the monks in the morning.

“You see me now.” His grin was nauseating. “How about keeping me company?”

“Can I get you a drink? Maybe a glass of—” I glanced at my tray. The gentleman looked like he couldn’t take another drop of either the grape or the grain. “Squash? Fresh cherries.”

“I do like cherries.” His fingers ran up my other arm, clasping at the elbow supporting the tray. Not with anger, but an entirely different intention. Oh, dear.

“Mmm.” He leaned from close to very close, pawing my neck and stroking my hair. I couldn’t suppress a shiver. “Never seen such a short-haired girl. So pretty.”

The glasses were practically chiming a melody now. It wasn’t that I was disgusted at being mistaken for a girl. It was that—well, some might think that gentlemen would be nicer if they thought one were a pretty girl. But really—they weren’t.

I scanned the crowd, saw no help coming. Tibario would find me. One twinge of trouble and surely he’d swoop in with brotherly valor.

“Come here.” The man yanked my arm, sending wine spattering down the tray onto his cuffs. I should have screamed—I should have used my tray as a weapon. But for some reason, it seemed in that moment crucially important not to drop the tray. I had practiced and practiced keeping it flat against my palm, holding the posture so I wouldn’t get tired. It made me sore, but I’d proved I could do it. Dropping it now would just be too much—

The man jumped, slapping at his face. I flinched. Bright embers fell from him, leaving black ash lines on his skin as a cigarillo butt plopped at my feet.

A voice rose from the shadows. “Do you truly not have staff at home you can do this to?”

Someone had thrown a cigarillo at him.

The flare of a match illuminated the speaker. A man, sitting by the fountain, even larger than my unwanted guest. He stood, grand in his darkness, the cigar flash of the next puff not revealing his face. Only his eyes caught the light, magnifying it and painting it silver.

I backed by instinct against the trees as my unwelcome suitor bellowed and threw a swing at the newcomer. It was a clean boxer’s blow, but the shadowed fellow snared it like he was catching a stone, yanked the man off his feet by his cravat, and dunked him, face first, into the fountain.

I winced at the sound of gargling.

The

drunkard came up heaving; the dark gentleman daintily lifted his cigarillo and breathed a cloud of smoke into the fellow’s face. “Well. Now that your evening is quite shot to hell, why don’t you do the noble thing and fuck right off? There’s a lad.”

He let the fellow down on feet so unsteady the man nearly hit the fountain again. The jarring motions must have put the last straw on a drunken camel’s back. He covered his mouth, dashing out of the courtyard to retch out of view.

I realized, then, how close I was to tears. Gratitude made my knees weak, but I couldn’t relax yet. After all, I didn’t know my savior any more than the first man. His shape was vast, and so shifting and black he could have been an avatar of the night. He appeared to smirk from his crown of shadows and took another puff.

He was looking at me. I tried to turn away, but found I couldn’t. The animal clarity of his gaze was transfixing, stubbornly luminous as if to spite the dimness.

He inclined his head as if to acknowledge me. “I suppose you get this sort of thing all the time, because of your voice.”

“I suppose I do.” I couldn’t gauge his sobriety, but he was certainly quicker than the average drunk. “It’s not much expected anymore.” I hoped he let it end there. Castrating boys had been made illegal before the revolution, and I was no true castrato. Not by a knife, anyway. No doubt to these gentlemen I was as much a sparkling anomaly as any operatic diversion, but I was tired of explaining how I worked.

“I also suppose I’ll stay here for a moment, until the coast has cleared, as it were.” Casually, a gesture of nothing made. Exactly what I wanted.

“Yes.” I breathed, deeply. “Thank you, signor. I am grateful.” I should have shown him some greater favor, or dropped all and run. But there was another cause for joy: I had not spilled another drop of wine. Somehow that felt positively heroic.

A stone column stood nearby, so I lowered my tray onto it. My arm protested the sudden movement, and the tray tipped. The gentleman appeared at my side and caught it with such grace it could have been magic. “Allow me. Seems you should have a drink yourself.”

I smiled but declined. The last thing I needed was to lose self-control. I was calmer now that the crisis had passed, and I took my first clear view of him.

Tall as a temple statue, and as striking. A smooth face under hair as dark as an ink swipe. And though it was subtle at first, a strong accent curled through his voice, lacing each word with trills and rough edges.

“Then look the other way as I partake.” He took a glass of sherry. The flute looked hilariously small between his fingers as he sipped. A ruby-colored bead escaped from the corner of his lip, leaving a trail down his chin that he wiped with one hand. “Mm. You know what I ought to have done? Gotten red-mouthed with drink, then threatened to eat him whole for his transgressions. Baring my teeth for effect.”

By way of example, he sloshed sherry in his mouth and flexed his jaw with a theatrical snarl. The garnet gleam of the liquid lent him a dramatic air, but most striking were his teeth.

Or rather, fangs. Two long canines, all but glittering like knifepoints.

Two realizations pierced me, like the ends of those fangs. One swam out of the debris of the night—the man’s strange atmosphere, his lingering in the shadows. His uncanny strength. The reflective sheen of his eyes. From it all emerged a word: moon-soul.

Women and men who’d been called back from death, the spirits of noble beasts beating within their human hearts. They were made new, and immortal, by the strange virtue of the moon. My understanding was that the noble spirits never resurrected mages like Mamma or myself out of fear of magic, but moon-souls had mysterious powers of their own. Packs and flocks of shape-changing elite had once ruled this country. Now, the chances of coming across one of his kind should have been small.

The second realization was softer but deeper—I was still laughing at his joke, unshaken by what he’d revealed. The reverence or fear that so many still felt for moon-souls had never marked my life. Not like it had Tibario’s, or even Mamma’s. I knew the polite thing to do: kneel before him. Speak the name of his soul’s animal, if I knew it. Lord Lupo, Lord Orso, or whatever it happened to be. Avoid his gaze in obeisance.

Yet...he was laughing with me, making no demands. His unexpected aid and easy manner were kindnesses that I had desperately needed tonight. Perhaps if my first impression of him had been less picturesque, I wouldn’t have felt so moved to see him in such a soft light. It was difficult not to warm to someone who’d defended me so effortlessly, and who’d asked nothing for it. I could not forget the sheer drama of him throwing a cigarillo in the other man’s face.

Tibario and Mamma would likely distrust him, with his cool supernatural air and subtle audacity. But something deep and wordless stirred with him as I heard his laughter, as if a dark place in me was responding to his shadowy grandeur.

He might be moved to offer one more kindness, if I dared ask.

His grin widened. “Too far? Sherry doesn’t look enough like blood to give a proper illusion. Maybe I could taste a nip from your veins, eh?” He waggled an eyebrow. I’d read that moon-souls sometimes drank blood, though usually not human blood. And there was simply no way to read a real threat in it.

I chuckled gently. “Would have lent your performance credence, anyway.” But my humor was dying. If I wanted to act, it had to be soon. “Signor, I—”

“While we’re on that.” He winked and shook the last drop from his glass. “It’s not ‘signor.’ It’s ‘my lord.’”

I glanced around us, at the golden cloud of lies that both suffocated and shielded me. I hadn’t expected a chance to escape my fate, but this might be an open window. If his curious gentleness was not merely the fantasy of my flustered misery, and if it would move him to heed my plea. In my pocket was a fold of papers. Shaking, I pulled it out, dipped my fingertip into the reddest of my wines.

A flash of blue in the crowd—Tibario, with hell bright on his face. His swagger told me the target had been found and he needed only to collect me.

I painted my message on the paper. The gentleman raised an eyebrow as I folded it up and hid it against my wrist.

I knelt before him. My bowed head scarcely rose above his knees. Before he could react, I took his fingers and clasped them in my hands.

“Then, my lord,” I said, “I pray you will forgive how irreverently I spoke to you this evening. You have my thanks.”

I kissed his fingertips. He scoffed, but as I drew my lips away, I slid the paper into his hand.

“Pardon me, may I borrow you for a moment?” Tibario was upon us, bearing the authority of his priestly disguise.

I met the lord’s eyes—and did not dare stand until his fist closed around my message. I looked up at Tibario, firmly in character. “How can I help you, Your Grace?”

“A few hands inside the Duomodoro for a private party, if you please? His Grace would like some drink. Excuse my interruption, signor.”

The strange gentleman—lord, rather—frowned. He was covertly peeking at my note. I restrained myself from pleading with my eyes.

Tibario had a hold of my arm, clutching too tightly. “Good evening.” He pulled me along with concealed urgency.

Hurrying to keep up, I glanced back at the lord. He watched us go, all the warmth stripped from his eyes. If he understood, he made no move to act. Perhaps he could not.

I breathed deeply, steeling myself. And raised my message in prayer.

Stop me.

Please.

Tibario loosened his grasp once we were inside the Duomodoro. No one else was in the hall. Ivory linings lent the cathedral a mausoleum-like air.

Sniffing scornfully, Tibario seized my tray and dumped it behind a pillar. Those poor glasses. If he’d known how I’d fought for them. He tossed the silver disc aside with a clang then dusted his hands. “All right. What in hell were you doing with him in the corner? I told you to stay in sight where it was safe.”

Tibario and I didn’t look greatly like brothers; we both had Mamma’s delicate nose and fair eyes, but he was burnished as an olive, hair equally rich. And he, not having my condition, looked unmistakably male. Proper muscles and all.

“I wasn’t trying to—”

“Dammit, Mio, do you know how much danger you could have been in? That man looked like he wanted to eat you with minuet sauce.”

“

He—” I was going to say that he’d saved me. But then I would have to say from what he’d saved me. And if he recognized the lord as a moon-soul, he’d probably lecture me on the bad influence of superhumanly strong immortals. “He kept me company.”

“Never mind.” Tibario sighed, and wrapped one arm affectionately around my narrow shoulders. “I’m here now.”

“Thank you, brother.” I allowed myself to lean into him.

“Mamma has him in the meeting room.” Tibario retrieved the silver tray and used its reflection to adjust the swirl of his pompadour. “Warm up your voice. It’s just about time.”

The tension in my chest would bow to no warm-up. I nodded anyway. “I’m ready.”

He kept his arm around me protectively during the approach. The false acolyte and the witch’s serving boy, holding on to each other. The two of us and Mamma, cornering a man of the cloth to break his will for the cause. Like a family.

Well. Like our family.

Papa would have joined in the bonding himself, but he was overseeing his soldiers. No worry. Failure was never acceptable, but with Mamma at the helm? It wasn’t even possible.

I began to hum a little tune, more to comfort myself than for practice. The only melody I could think of was a dirge.

We were admitted into a habit-blue room spotted with festival lights. Tibario closed the door behind us, and at once I lost sense of how I had gotten there. The room was like the enclosure of a dream, marking out a world of its own against the celebrations outside. A priest, garbed in azure, sat by the stained glass window. There, the room’s dreamlike aura thickened, but not around him. It was around the woman seated across from him, who charged the air with possibilities.

Queen of the illicit phylactery trade in Vermagna, witch nonpareil, and mistress of the power of occhiorosso. My mother, Serafina Gianbellicci.

She smiled at me, the ruby glint of her left eye a dagger’s point. Her magic and mine touched and mingled like two instruments finding harmony.

His Grace—Pater Donatello—was a reedy man who would have looked heartbreakingly ordinary if not for his blue chasuble, and the knowledge that he might soon be one of our country’s leaders. This was going to be hard. “Signora Gianbellicci and I have been having the most fascinating discussion. Do fetch some wine for the good signora,” he told me.

“Oh, no, really, thank you, Your Grace. I abstain.”

Of course she abstained, like almost all mages. Unlike most mages, she never wore any periapts, jeweled mediums that armored the fragile magical organs. She forbade me to wear them either; to her, they were signs of shame. When I became a witch like her—a mage capable of working one’s natural magic into spells—she’d said I’d have to control unassisted the magic that pulsed through my body like blood.

Mine was awakening from my humming. Every mage had a part of their body in which their magic dwelled. Mamma’s was in her left eye, but mine was in my throat. Music opened a new plane of my senses. Emotion, thought, intention, my heart picked up all these vibrations

like a tuning fork. Through that magic link flowed the purr of the priest’s discomfort, and Tibario’s eager tension. A heavy beat thrummed under it all—Mamma’s elation with her caught prey.

“Pater, I’d like to introduce my son Mio.” She indicated me. I felt a strange urge to do something exhibitory, like dance for him, but resisted. I was already going to sing.

“Ah, how do you do? How novel to have a child in service. But war has changed much for us all.” He shook my hand.

“His Grace was just telling me what he planned for laws of magic when he’s elected consul.” Mamma directed this at me, as if sharing a small gift. This is my magic son. He does tricks.

“If I am elected consul, signora.” He chuckled. “I hope to see a future with more freedom for your kind. The church feels no qualm against mages or witches so long as they do not stray into sorcery—after all, magic which manipulates the wills of others must be anathema to any sane being.”

The subject made me queasy. My childhood had been rife with tales of other countries in which mages were institutionalized, subdued with drugs that slowed the mind and numbed the body. Our once-feudal country had never had quite the same traditions, and the teetering new government had no power to enforce such a thing. But magical arts were either treated as commodities, or harshly policed by officials. His promises didn’t exactly kindle my optimism.

“Sorcery truly is a repugnant practice. Don’t you agree, my son?” She tilted her head.

I stared.

“Quite.” Donatello nodded primly. “The mind is a sacred boundary. I believe laws should focus on fighting sorcerers and not inhibiting theurgy that benefits society.”

“You see, Your Grace? You have secured my confidence.” She blinked so quickly that for a moment she appeared lidless. “And the number of votes I can assure you.”

He shook his head with a sufficiently abashed laugh. “I appreciate the public support, signora. But my understanding was that neither you nor your husband possessed a seat on the electorate.”

But the tune of his apprehension rang clear to me beneath his politesse. At first, I’d hoped she would try to bargain with him, her influence for his obedience. She already controlled puppets in both houses of the government. He could simply volunteer to be one—and I would be the last resort if he refused.

But I should have known better. She played much simpler, more ambitious games. Of course she wouldn’t give him a choice.

“Indeed. I do not possess a seat on the electorate.” She smiled, an acid-and-honey streak across her face. “I possess several.”

His thoughts were chimes against my senses. Like me with my strange lord, the signs were coalescing into a pattern for Donatello. The fact that she’d asked him here in secret, at such an

unusual time and place. Her hypnotically cryptic remarks. And a thousand chilling rumors of a witch with a red eye.

She was toying with him, showing him her hand. Proving that it was far too late to fold. I’d wondered how many people actually knew that Mamma had exerted dominion over members of the governing seats. But the taste was in the air, the city’s stones reeking of sorcery—magic that controlled the mind. Donatello was no doubt beginning to recognize that taste.

His rapidly uncoiling fear sent a chill through me, made me wish to close the link. But the inner music continued its soft flooding of my skin. I felt the vibrations so delicately now that I might have been able to tell apart every particle of my flesh; each note was capable of changing me on a physical level. Often after singing, I found that scratches and bruises on my body had spontaneously healed.

I wouldn’t be healing anything tonight.

“Signora... I’m afraid I have no means to unravel such riddles.”

Mamma’s resonance trilled sharply. She stood and gazed out the window. Festival lights mottled her face as if numbering her countless sins. Our countless sins. She swung the gold chain up against the glass. “Do you know the most valuable currency in our fair city, Your Grace?”

Nerves made him speak quickly. “The economy struggles, true, but I intend—”

“Loyalty. No coin weighs more than loyalty. Money itself is but a symbol of loyalty, a trust in the value of a nation. That loyalty can be bought is no failing, but a need. Elsewise new trusts might not be forged.”

I wondered what kind of secret Pater Donatello would have. I hoped his was mortifying, filthy. A child killer. A rapist. A slaver or a brutalizer. If he was rotten to his core, perhaps I would come away feeling I had helped Mamma cleave a path for justice.

“That may be true, signora, but I assure you my loyalty is not for sale.”

He was taking a stand. The feeling of his resolution firming made me nauseous.

Please, please let him just be terrible.

“Oh, Your Grace! I am not asking to buy your loyalty.” Mamma laughed, turning to face him. With one slow movement, she pressed the gem against the glass and dragged a scraping cut down its length. “I intend for you to pay for mine.”

Donatello surged to his feet, intent on the door. Tibario barred his path.

“Apologies, Your Grace.” Tibario produced a pistol from his belt, then locked the door with a snap. “I’m afraid I’ll have to ask you to take your seat.”

The priest obeyed with hands poised on his knees. He was still holding on to his strength inside, assuring himself that if she wanted him dead, she’d have him killed in a way that could not implicate her or her son.

I hated this, too. I hated how I could hear their internal struggle every single time.

“What do you wish for me to do, then, signora? I have no power that would satisfy you. And even as consul, I would not command the entire country.” His voice, admirably, did not shake.

Mamma gestured me forth. Her occhiorosso was already glowing. It looked hungry for secrets, for purchase into his mind. I came to stand before him. “All I want you to do,” she said, very slowly, as if explaining something to a child, “is listen to my son sing.”

Confusion rattled through him. Before he could ask, she took me by the chin and kissed me lightly on the nose. “Now, Mio.”

I looked at Donatello. His heartbeat marked my time, set a rhythm I could spin a ballad out of with ease. And I knew by that cadence that whatever shadows he had in him, none of them were as terrible and ugly as I hoped. I couldn’t do this again.

“It’s all right, my boy,” she breathed in my ear. “Never fear.”

Never fear.

I began to sing.

It felt morbid to pick out a piece for each victim. If I chose a threnody, it would only compound the horror of the violation in their memory. A mattinata, and the cheer of such music would be polluted forever in their ears. For him, I had selected an aria. Lifting my voice to its height, I composed the theme to Pater Donatello’s undoing.

I strung the beats into place, slipping gently into a contralto, and as my tempo mounted the song rose like floodwater around him. The vibration of my heart rushed out with it, ...

eye.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...