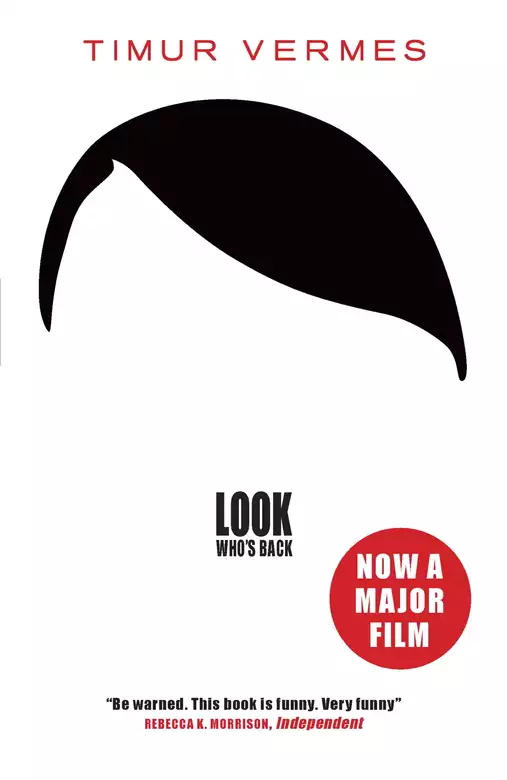

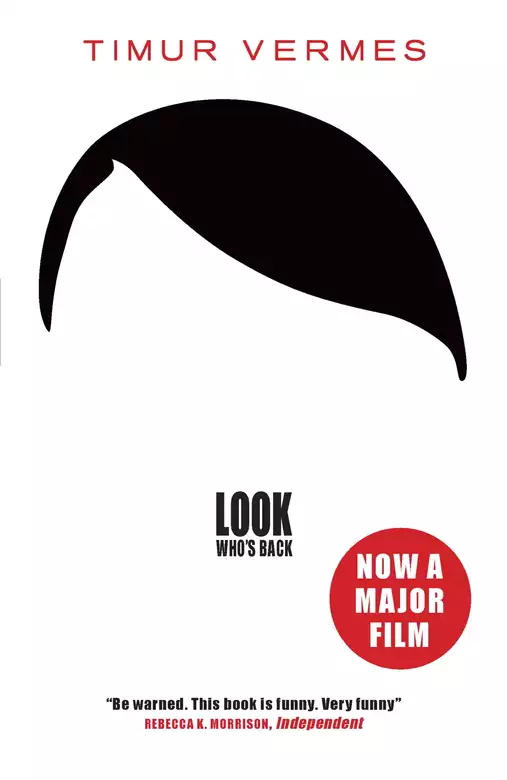

Look Who's Back

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Berlin, 2011. Adolf Hitler wakes up on the ground, alive and well. Everything has changed, Hitler barely recognises his beloved Fatherland. People recognise him though, as an excellent impersonator. The inevitable happens, and ranting Hitler becomes a YouTube star, gets his own TV show, becoming someone who people listen to. All while he's still trying to convince people that yes, it really is him, and yes, he really means it.

Release date: March 27, 2014

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Look Who's Back

Timur Vermes

To begin with, at any rate.

It could no longer be denied that the German Volk had ultimately proved itself inferior in the epic struggle against the English, against Bolshevism, against imperialism, thereby – and I will not mince my words – forfeiting its future existence, even at the most primitive level as hunter-gatherers. Accordingly, it lost its right to waterworks, bridges and roads. And door handles, too. This is the reason I issued my directive. It must be said that I also did it in part for the sake of thoroughness, for when I took the odd stroll outside the Reich Chancellery I had to concede that with their Flying Fortresses, the Americans and the English had already relieved us of a substantial volume of the work. Naturally, after the directive was issued, I did not monitor in every minute detail how it was executed. The reader will appreciate how much else I had to do: grappling with the Americans in the West, resisting the Russians in the East, planning the development of the world’s capital city, Germania. In my opinion the Wehrmacht should have been able to cope with any remaining door handles. And this Volk should no longer exist.

As I have now established, however, it is still here.

A fact I find rather difficult to comprehend.

On the other hand, I am here too, and I cannot understand that either.

I remember waking up; it must have been early afternoon. Opening my eyes I saw above me the sky, which was blue with the occasional cloud. It felt warm, and I sensed at once that it was too warm for April. One might almost call it hot. It was relatively quiet; I could not see any enemy aircraft flying overhead, or hear the thunder of artillery fire, there seemed to be no shelling nearby or explosions, no air-raid sirens. It also struck me that there was no Reich Chancellery and no Führerbunker. I turned my head and saw that I was lying on an area of undeveloped land, surrounded by terraces of houses. Here and there urchins had daubed the brick walls with paint, which aroused my ire, and I took the snap decision to summon Grand Admiral Dönitz. Still half asleep, I imagined that Dönitz must also be lying around here somewhere. But then discipline and logic triumphed, and in a flash I grasped the peculiarity of the situation in which I found myself. I do not usually camp out.

My first thought was, “What did I get up to last night?” Seeing as I do not drink, I could rule out any overindulgence in alcohol. The last thing I recalled was sitting on a sofa, a divan, with Eva. I also remembered that I was – or we were – feeling rather carefree; just for once I had decided to put the affairs of state to one side. We had no plans for the evening. Naturally there was no question of going out to a restaurant or to the pictures – entertainment in the capital was gratifyingly thin on the ground, largely as a result of my directive. How could I be sure that Stalin would not be arriving in the city in the coming days? At that point in the war such a turn of events could not be dismissed out of hand. What was absolutely certain was that he would be as unlikely to find a picture house here as he would in Stalingrad. I think Eva and I chatted for a while, and I showed her my old pistol, but when I awoke I was unable to recall any further details. Not least on account of the bad headache I was suffering from. No, my attempts to piece together the events of the previous evening were leading nowhere.

I thus decided to take matters into my own hands and get to grips with my situation. Over the course of my life I have learned to observe, to reflect, to pick up on even the smallest detail to which many learned people pay scant heed, or simply ignore. Thanks to years of iron discipline, I can say with a clear conscience that in a crisis I become more composed, more level-headed, my senses are sharpened. I work calmly, with precision, like a machine. Methodically, I synthesise the information at my disposal. I am lying on the ground. I look around. Litter is strewn beside me; I can see weeds and grass, the odd bush, a daisy, and a dandelion. I can hear voices shouting – they cannot be far away – the noise of a ball bouncing repeatedly on the ground. I look in the direction of these sounds, they are coming from a group of lads playing association football. Not little boys anymore, but probably too young for the Volkssturm. I expect they are in the Hitler Youth, although evidently not on duty. For the time being the enemy appears to have ceased its onslaught. A bird is hopping about in the boughs of a tree; it tweets, it sings. Most people will simply interpret such behaviour as a sign of happiness. But in this uncertain situation the expert on the natural world and the day-to-day battle for survival exploits every scrap of information, however small, and infers that no predators are present. Right beside my head is a puddle which appears to be shrinking; it must have rained, but some time ago now. At the edge of the puddle is my peaked cap. This is how my trained mind works; this is how it worked even then, in a moment of confusion.

I sat up without difficulty. I moved my legs, hands and fingers. I did not appear to be injured, my physical state was encouraging; but for the sore head I was in rude health. Even the shaking which usually afflicted my hand seemed to have subsided. Glancing down I saw myself dressed in full military uniform. My jacket had been soiled, but not excessively so, which ruled out the possibility of my having been buried alive. I could identify mud stains and what looked like bread or cake crumbs, or similar. The fabric reeked of fuel, petrol perhaps; Eva may have used too much solvent to clean my uniform. It smelled as if she had emptied a whole jerrycan of the stuff over me. Eva was not to be seen, nor did any of my staff appear to be in the immediate vicinity. As I was brushing the most conspicuous specks of dirt from the front of my coat and sleeves, I heard a voice:

“Hey guys, check this out!”

“Whooooa, major casualty!”

I seemed to have given the impression that I needed help, and this was admirably recognised by the three Hitler Youths. Even though they were off the mark with my rank. They stopped their game and approached me respectfully. Understandably so – to find oneself all of a sudden face to face with the Führer of the German Reich amongst daisies and dandelions on a patch of wasteland generally used for sport and physical training is an unusual turn of events in the daily routine of a young man yet to reach full maturity. Nonetheless the small troop hurried over like greyhounds, eager to help. The youth is the future!

The boys gathered around me, but kept a certain distance. After affording me a cursory inspection, the tallest of the youths, clearly the troop leader, said:

“You alright, boss?”

Despite my apprehension, I could not help noticing that the Nazi salute was missing altogether. I acknowledge that his casual form of address, mixing up “boss” and “Führer”, may have been a consequence of the surprise factor. In a less confusing situation it might have been unintentionally comic – after all, had not the most farcical events occurred in the unremitting storm of steel of the trenches? Even in unusual situations, however, the soldier must have certain automatic responses; this is the point of drill. If soldiers lack these automatic responses, then the army is worthless. I stood up, which was not easy as I must have been lying there for a while. But I straightened out my jacket and attempted a makeshift dusting of my trousers with a few gentle slaps. Then I cleared my throat and asked the troop leader, “Where’s Bormann?”

“Who?”

Unbelievable!

“Bormann! Martin!”

“Don’t know who you’re on about.”

“Never heard of him.”

“What’s he look like?”

“Like a Reichsleiter, for pity’s sake!”

Something was very amiss. I was obviously still in Berlin, but I appeared to have been deprived of the entire apparatus of government. I had to get back to the Führerbunker – urgently – and it was as clear as daylight that the youths around me were not going to be a great deal of help here. The first thing I needed to do was orient myself. The featureless piece of land where I now stood could have been anywhere in the city. I had to get to a street; in this protracted ceasefire surely there would be enough passers-by, workers and motor-cab drivers to point me in the right direction.

I expect my needs did not appear sufficiently pressing to the Hitler Youths, who looked as if they wanted to resume their game of association football. The tallest of the lads now turned to his friends, allowing me to read his name, which his mother had sewn onto a brightly coloured jersey.

“Hitler Youth Ronaldo! Which way to the street?”

The reaction was feeble; I am afraid to say that the youths practically ignored me, although as he shuffled past one of the two younger ones pointed limply to a corner of the wasteland. Peering more closely I could see that there was indeed a thoroughfare in that direction. I made a mental note to have Rust dismissed. The man had been Reich Minister for Education since 1934, and there is no place for such abysmal sloppiness in education. How is a young soldier supposed to find the victorious path to Moscow, to the very heart of Bolshevism, if he cannot even recognise his own supreme commander?

I bent down, picked up my cap and, putting it on, walked steadily and purposefully in the direction the boy had indicated. I went around a corner and made my way between high walls down a narrow alleyway towards the brightness of the street. A timid and bedraggled cat with a coat of many hues sloped past me along the wall. I took four or five more steps and then emerged into the street.

The violent onslaught of light and colour took my breath away.

The last time I had seen it I remembered the city being terribly dusty and a kind of field-grey, with heaps of rubble and widespread damage. What lay before me now was quite different. The rubble had vanished, or at least had been removed, the streets cleared. Instead there were numerous, nay innumerable brightly coloured vehicles on either side of the street. They may well have been automobiles, but were smaller, and yet they looked so technically advanced as to make one suspect that the Messerschmitt plant must have had a leading hand in their design. The houses were freshly painted, in a variety of colours, reminding me of the confectionery of my youth. I admit, I began to feel faintly dizzy. My eyes sought something familiar, and on the far side of the carriageway I spied a shabby park bench on a strip of grass. I ventured a few steps, and I am not ashamed to say that they may have seemed quite tentative. I heard the ring of a bell, the screeching of rubber on asphalt, and then somebody screamed at me:

“Oi! What’s your game? Are you blind or what?”

“I … I’m terribly sorry,” I heard myself say, both shaken and relieved. Beside me was a bicyclist, this at least was an image I was comparatively familiar with. Added to that, the man was wearing a protective helmet, which appeared to have sustained some serious damage given the number of holes in it. So we were still at war.

“What the hell do you think you’re doing, staggering around like that?”

“I … pardon me … I … need to sit down.”

“I suggest you take a lie down, pal. And make it a nice long one!”

I found sanctuary on the park bench; I expect I was somewhat pale when I slumped onto it. This young man did not seem to have recognised me, either. Again, there was no Nazi salute; from his reaction one would have thought he had almost collided with any old passer-by, a nobody. And this negligence seemed to be common practice. An elderly gentleman walked past me, shaking his head, followed by a hefty woman pushing a futuristic perambulator – likewise a familiar object, but it offered no help out of my desperate situation. I stood up and approached her with as much outward confidence as I could muster.

“Excuse me, now this may come as something of a surprise, but I … I urgently need to find my way to the Reich Chancellery.”

“Are you on the Stefan Raab Show?”

“I’m sorry?”

“Or Kerkeling? Harald Schmidt?”

It may have been nervousness which triggered my impatience; I grabbed her by the arm.

“Pull yourself together, woman! As a fellow German you have your duties and obligations! We are at war! What do you think the Russians would do to you if they got here? Do you honestly think a Russian would glance at your child and say, ‘Well, what a fine young German girl we have here, but for the child’s sake I will leave my baser urges in my trousers?’ At this very hour, on this very day, the future of the German Volk, the purity of German blood, indeed the survival of humanity itself is at stake. Do you wish to be responsible for the end of civilisation merely because, in your extraordinary stupidity, you are unwilling to show the Führer of the German Reich the way to his Reich Chancellery?”

The lack of a helpful response had almost ceased to be a surprise. This imbecilic woman shook her sleeve from my grasp, glared at me dumbfounded, and tapped the side of her head with her index finger: an unequivocal gesture of disapproval. I had to accept the truth of the matter; something here had spiralled completely out of control. I was no longer being treated like a commander-in-chief, like a Reichsführer. The footballers, the elderly gentleman, the bicyclist, the perambulator woman – this was no coincidence. My first instinct was to notify the security agencies, to restore order. But I curbed this instinct. I had insufficient knowledge of my circumstances. I needed more information.

With ice-cool composure my methodical brain, now functioning again, recapped the situation. I was in Germany, I was in Berlin, even though the city looked wholly unfamiliar to me. This Germany was different, but some of its aspects reminded me of the Reich I was familiar with. Bicyclists still existed, as did automobiles, so probably newspapers still existed too. I looked around. And under my bench I did find something resembling a newspaper, albeit printed far more lavishly. The paper was in colour, something new to me. It was called Media Market – for the life of me I could not recall having given my approval to such a publication, nor would I ever have approved it. The information it contained was totally incomprehensible. Anger swelled within me: how, at a time of paper shortage, could the German Volk’s valuable resources be squandered on such mindless rubbish? As soon as I got back to my desk, Funk was going to get a proper dressing-down. But at that moment I needed some reliable news, a Völkischer Beobachter, a Stürmer; Why, I’d have settled for the local Panzerbär, which had only been going for a few issues. I spotted a kiosk not too far away, and even from that distance I could make out an extraordinary array of papers. You could have been forgiven for thinking we were deep in the most indolent peacetime! I got up impatiently. Too much time had already been lost – now order must be restored as rapidly as possible. Surely my troops were awaiting orders; it was quite possible my presence was sorely needed elsewhere. I hurried to the kiosk.

Even a cursory look furnished me with some useful information. Myriad colourful papers hung on the outside wall – in Turkish. A large number of Turks must now be living in this area. I must have been unconscious for a significant period of time, during which waves of Turks had descended on Berlin. Remarkable! After all, the Turk, essentially a loyal ally of the German Volk, had persisted in remaining neutral; in spite of all our efforts, we had never been able to get him to enter the war on the side of the Axis powers. But now it seemed as if during my absence someone – Dönitz, I imagine – had convinced the Turk to lend us his support. Moreover, the comparatively peaceful atmosphere on the streets suggested that the deployment of Turkish forces had brought about a decisive turning-point in the war. Yes, I had always harboured respect for the Turk, but would never have imagined him capable of such an achievement. On the other hand, a lack of time had precluded my having followed the development of that country in any great detail. Kemal Atatürk’s reforms must have given the nation a sensational boost. This seemed to have been the miracle on which Goebbels had always pinned his hopes. Full of confidence, my heart was now pounding. My refusal to abandon faith in ultimate victory, even in the deepest, darkest hour of the Reich, had paid off. Four or five Turkish-language publications, all printed in bright colours, were unmistakable proof of a new, triumphant Berlin–Ankara axis. Now that my greatest concern, my concern for the welfare of the Reich, appeared to have been assuaged in such a surprising manner, I had to find out how much time I had spent in that strange twilight on the patch of waste ground. Unable to see a Völkischer Beobachter anywhere – obviously it had sold out – I cast about for the most familiar-looking paper, which went by the name Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. It was new to me, but unlike some of the others displayed there, I was heartened by the reassuring typeface of its title. I didn’t bother with any of the news reports; I was looking for the date.

It said 30 August.

2011.

I gaped at the number in amazement, in disbelief. I turned my attention to a different paper, the Berliner Zeitung, which also displayed an exemplary German typeface, and sought out the date.

2011.

I tore the newspaper from its bracket, opened it and turned a page, then another one.

2011.

The number began to dance before my eyes, as if mocking me. It moved slowly to the left, then back again more quickly, swaying like a group of revellers in a beer tent. My eyes tried to follow the number, then the paper slipped from my grasp. I felt myself sinking; in vain I tried to clutch at other newspapers on the rack. I slid to the ground.

Then everything went black.

When I regained consciousness I was still lying on the ground. Something damp was being pressed against my forehead.

“Are you O.K.?”

Bent over me was a man who may have been forty-five, or even over fifty. He was wearing a checked shirt and plain trousers – a typical worker’s outfit. This time I knew which question to ask first.

“What is today’s date?”

“Ermm … 29 August. No, wait, it’s the thirtieth.”

“Which year, man?” I croaked, sitting up.

He frowned at me.

“2011,” he said, staring at my coat. “What did you think? 1945?”

I tried to come up with a fitting riposte, but thought it more prudent to get to my feet.

“Maybe you should lie down a little longer,” the man said. “Or at least sit. I’ve got an armchair in the kiosk.”

My first instinct was to tell him that I had no time to rest, but I had to acknowledge that my legs were still shaking. So I followed him into the kiosk. He sat on a chair near the vending window and stared at me.

“Sip of water? How about some chocolate? Granola bar?”

I nodded in a daze. He stood up, fetched a bottle of soda water and poured me a glass. From a shelf he took a colourful bar of what I took to be some sort of iron ration, wrapped in foil. He opened the wrapping, exposing something that looked like industrially pressed grain, and put it in my hand. There must still be a bread shortage.

“You should have a bigger breakfast,” he said, before sitting down again. “Are you filming nearby?”

“Filming … ?”

“You know, a documentary. A film. They’re always filming around here.”

“Film … ?”

“Goodness me, you’re in a right state.” Pointing at me, he laughed. “Or do you always go around like this?”

I looked down at myself. I didn’t notice anything out of the ordinary apart from the dust and the odour of petrol.

“As a matter of fact, I do,” I said.

Perhaps I had suffered an injury to my face. “Do you have a mirror?” I asked.

“Sure,” he said, pointing to it. “Right next to you, just above Focus.”

I followed his finger. The mirror had an orange frame, on which was printed “The Mirror”, just for good measure, as if this were not obvious enough. The bottom third of it was wedged between some magazines. I gazed into it.

I was surprised by how immaculate my reflection appeared; my coat even looked as if it had been ironed – the light in the kiosk must be flattering.

“Because of the lead story?” the man asked. “They run those Hitler stories every three issues nowadays. I don’t reckon you need do any more research. You’re amazing.”

“Thank you,” I said absently.

“No, I really mean it,” he said. “I’ve seen Downfall. Twice. Bruno Ganz was superb, but he’s not a patch on you. Your whole demeanour … I mean, one would almost think you were the man himself.”

I glanced up. “Which man?”

“You know, the Führer,” he said, raising both his hands, crooking his index and middle fingers together, then twitching them up and down twice. I could hardly bring myself to accept that after sixty-six years this was all that remained of the once-rigid Nazi salute. It came as a devastating shock, but a sign nonetheless that my political influence had not vanished altogether in the intervening years.

I flipped up my arm in response to his salute: “I am the Führer!”

He laughed once more. “Incredible, you’re a natural.”

I could not comprehend his overpowering cheerfulness. Gradually I pieced together the facts of my situation. If this were no dream – it had lasted too long for that – then we were indeed in the year 2011. Which meant I was in a world totally new to me, and by the same token I had to accept that, for my part, I represented a new element in this world. If this world functioned according to even the most rudimentary logic, then it would expect me to be either one hundred and twenty two years old or, more probably, long dead.

“Do you act in other things, too?” he said. “Have I seen you before?”

“I do not act,” I said, rather brusquely.

“Of course not,” he said, putting on a curiously serious expression. Then he winked at me. “What are you in? Have you got your own programme?”

“Naturally,” I replied. “I’ve had one since 1920! As a fellow German you are surely aware of the twenty-five points.”

He nodded enthusiastically.

“But I still don’t recall seeing you anywhere. Have you got a card? Any flyers?”

“Don’t talk to me about the Luftwaffe,” I said sadly. “In the end they were a complete failure.”

I tried to work out what my next move should be. It seemed likely that a fifty-six-year-old Führer might meet with disbelief, even in the Reich Chancellery and Führerbunker; in fact he was certain to. I had to buy some time, weigh up my options. I needed to find somewhere to stay. Then I realised, all too painfully, that I had not a pfennig on me. For a moment unpleasant memories were stirred of my time in the men’s hostel in 1909. It had been a vital experience, I admit, allowing me an insight into life which no university in the world could have provided, and yet that period of austerity was not one I had enjoyed. Those dark months flashed through my mind: the disdain, the contempt, the uncertainty, the worry over securing the bare essentials, the dry bread. Brooding and distracted, I bit into the foil-wrapped grain.

It was surprisingly sweet. I inspected the product.

“I’m rather partial to them, too,” the newspaper vendor said. “Want another one?”

I shook my head. Larger problems faced me now. I needed a livelihood, however modest or basic. I needed somewhere to stay and a little money until I had a clearer perspective. Perhaps I needed to find a job, temporarily at least, until I knew whether and how I might be able to seize the reins of government again. Until then, a means of earning money was essential. Maybe I could work as a painter, or in an architect’s practice. And I was not above a bit of labouring, either – not at all. Of course, the knowledge I possessed would be more beneficial for the German Volk if it were put to use in a military campaign, but given my ignorance of the current situation this was an illusory scenario. After all, I did not even know which countries the German Reich now shared a border with. I had no idea who was hostile towards us, or against whom one could return fire. For now I had to content myself with what I could achieve with my manual skills – perhaps I could build a parade ground or a section of autobahn.

“Come on, be serious for a moment.” The voice of t. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...