- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

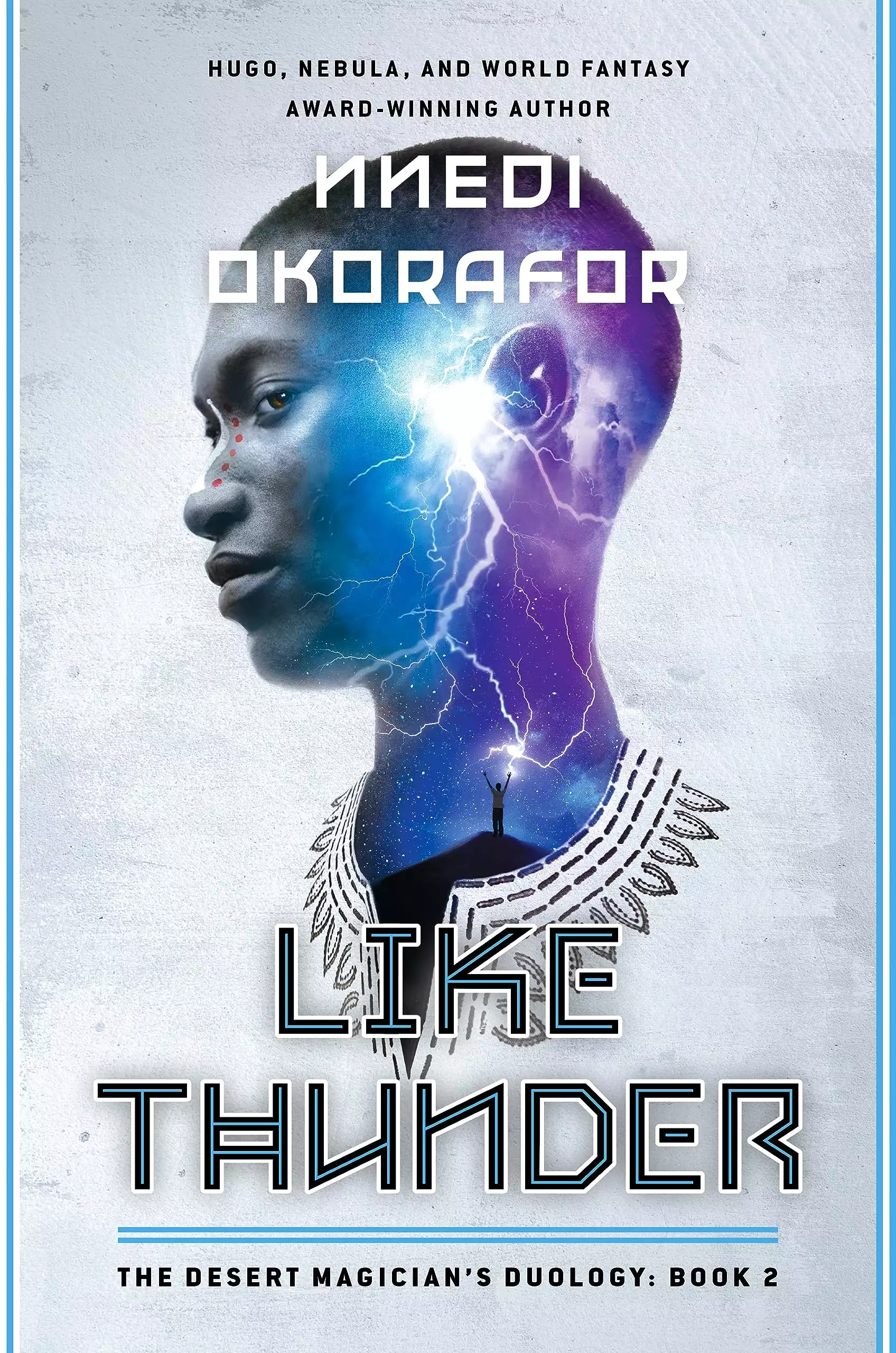

Synopsis

"An epic collision of new tech and elemental magic—suspenseful, immersive, and chillingly relevant. Another stunning feat of imagination from Nnedi Okorafor." —Leigh Bardugo, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Ninth House

Niger, West Africa, 2077

Welcome back. This second volume is a breathtaking story that sweeps across the sands of the Sahara, flies up to the peaks of the Aïr Mountains, cartwheels into a wild megacity—you get the idea.

I am the Desert Magician; I bring water where there is none.

This book begins with Dikéogu Obidimkpa slowly losing his mind. Yes, that boy who can bring rain just by thinking about it is having some…issues. Years ago, Dikéogu went on an epic journey to save Earth with the shadow speaker girl, Ejii Ubaid, who became his best friend. When it was all over, they went their separate ways, but now he’s learned their quest never really ended at all.

So Dikéogu, more powerful than ever, reunites with Ejii. He records this story as an audiofile, hoping it will help him keep his sanity or at least give him something to leave behind. Smart kid, but it won’t work—or will it?

I can tell you this: it won’t be like before. Our rainmaker and shadow speaker have changed. And after this, nothing will ever be the same again.

As they say, ‘Onye amaro ebe nmili si bido mabaya ama ama onye nyelu ya akwa oji welu ficha aru.’

Or, ‘If you do not remember where the rain started to beat you, you will not remember who gave you the towel with which to dry your body.’

Release date: November 28, 2023

Publisher: DAW

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Like Thunder

Nnedi Okorafor

CHAPTER 1

Better Told Than Written

I’ve seen so much.

I want you to imagine it.

So, as I said, I’m recording my words as an audio file on this damn near indestructible e-legba, a piece of portable tech so strong it outlasted the apocalypse. Sure, it looks pretty beaten up. That’s because it’s taken quite a beating. But no other personal device could do all that this one does, trust me. Recording something doesn’t even raise its processor-usage level, not even by a fraction. And it’s both solar and lunar. This recording will last.

Some things are better told than written. Maybe the old Africans had it right in initially making their traditions oral. Plus I’m more of a talker than a writer. I don’t have the patience to spend hours tapping on keys. Plus out here in the middle of the desert, I kind of like the sound of my voice.

And I’m an honest guy, not some mumu guy. Of all people, I don’t believe in gossip. Gossip is what got me in this mess in the first place. You can trust me. It’s okay to let your guard down. I’ll tell you no lies. No exaggerations. Fear no ego. No need for suspension of disbelief. This all happened and God help me now.

My friend Ejii liked to laugh about how I barely trusted anyone. She liked to exist in the naïve-nice-person-land where all humans, deep down, are good. I wonder what she thinks now, after so many have proven themselves to be cowards, liars, cheats, murderers, and lackadaisical pacifists who are happy to sit and watch innocent people die terrible deaths. Yeah, I said it. Someone has to. I know what I’ve seen. I know what I’ve had to do. And yeah, this thing is recording.

The Great Change was this weird combination of a nuclear apocalypse and the explosion of powerful juju called “Peace Bombs.” This messed up many of Earth’s laws of physics and brought down the wall between worlds. Then there was a pact of peace. It was written by noble genius baboons with black hands and soft brown fur that smelled like mint and grass. They wrote the pact in a magical language called nsibidi. This pact forced a truce between the evil inflated Chief Ette of Ginen’s Ooni Kingdom and the insanely heroic Jaa the Red One of the Sahara Desert. It stopped a war of the worlds, especially between Earth and the jungle planet Ginen. I’m damn proud to say that I was there and a part of why the pact was successful. So was Ejii, of course. She was a big deal that day.

That pact was some serious, deep, old mysticism. Even after all I’ve seen, I still find it amazing. That it happened at all is unbelievable. That it lasted for so long was nothing short of a miracle. For a few months

it kept the monster of war still, and for three years it held it at bay. But the pact eventually disintegrated, as it had to. But so did a lot of other things.

How do I explain all that happened? I’ll make it simple: eventually, all hell broke loose . . .

CHAPTER 2

Chocolate Factory

Right after the historic pact was made, I had important business to take care of. One problem solved (temporarily, at least), so on to the next one. I was focused, as was my owl Kola. And so was my mentor Gambo.

We all had reasons for going on this mission. For Gambo and me, it was because we’d both actually experienced slavery firsthand. Buji, Gambo’s co-husband, was just a guy who revered justice. When he saw injustice, he had to do something about it. The Nigérien Bureau of Investigation, a.k.a. the N.B.I., came with us because they were trying to cover their asses and not look like asses. As if they could prevent that. All these years and they knew nothing about what was happening in the northern part of what used to be Niger? Camelshit. They knew. And now they knew that if they didn’t do something they’d suffer hard-core sanctions and boycotts.

Gambo, Buji, Kola, and I had just left Ejii and Jaa in Kwàmfà. I was so excited to be going north with these people. After all that had happened. Toward this specific place. A place I hated.

Assamakka.

This place used to be a small innocent desert city with mazes of mud-brick homes, camels, goats, desert birds, scurrying lizards, women pounding millet, and men kneeling in prayer. But after the Great Change, when nuclear and Peace bombs fell and huge swaths of land here shifted from dead sand to lively sand and soil, opportunists made it the central headquarters of the cocoa industry. Most of the world’s cocoa used to make chocolate came from Assamakka and the farming towns around it. And all these places used cheap labor. Really cheap labor. Cheap young labor. Child slaves.

There is definitely a reason I hate chocolate. I’ll always hate it. I’d rather die than eat it. Chocolate was mixed with blood, sweat, and tears of children. It was a haunted confection. Way way back in 2003, Niger passed a law making slavery illegal. And even before that there were laws against child labor. These did nothing to stop it, though.

Even with all the spontaneous forests and new worlds and people and creatures dying and changing all over the place . . . you could still get chocolate. Anytime, anywhere. Common brown blocks of smooth delicious pleasure. Melted or solid. But no one wondered where it came from. How surprised you all would have been, o.

• • •

All I have to say about the land along the way is that it was dry, cracked, and full of nasty aggressive red beetles that tried to burrow into our tents at night. And they stained whatever you crushed them on. That didn’t stop me, though. I had garments stained with red dots to prove it.

This was just before we met up with the N.B.I. We didn’t see any spontaneous

forests and the weather was acceptable—meaning it was harsh and hot during the day but cool at night. Gambo and I wouldn’t have meddled with the weather regardless, even if we came across a severe storm. Even before we’d set out for Assamakka, he’d made sure to teach me that one should alter the weather sparingly or work with the will of nature.

“It’s irresponsible to do otherwise,” he said in his usual low rumbly voice. “A rainmaker who thinks he owns the sky is a rainmaker soon painfully killed by rain, snow, lightning, hail, or all of the above.”

About two days later, we stopped at a market for supplies—a second capture station for water, some new tents (those vile red beetles had eaten through two of ours), green tea, dried meat (a group of desert foxes had stolen much of ours), salt for the camels, a bag of millet to make tuagella (those thick crêpes that you eat with butter or sauce).

I remember all this because this turned out to be the last time we were in civilization for months. It was also where I bought this e-legba that I’m using to record my voice. Ejii had one that she liked to use to check the weather, play games, read books, and listen to music. I believe she lost it on the way to Ginen, though.

I used to have an expensive one back in my old life, before my parents sold me out. This new one that I got at the market wasn’t nearly as pricey, but I wasn’t complaining. It did what it needed to do. Of course, the e-legba I bought was nothing like the souped-up device it is now. Not yet.

We continued on our way, and what would happen next would shape everything that led me to where I am today.

• • •

About a day after leaving the market, we met up with a man named Ali Mamami. He was the head of the Nigérien Bureau of Investigation. He was a pretty intense guy. Ali liked to wear flowing garments that were so voluminous that you couldn’t tell if he was skinny or fat. He never smiled. He didn’t add sugar to his mint tea or use salt with his meals. He didn’t listen to music. The man was like petrified wood. You wonder what someone like that has seen to make him

that way. But I didn’t think he was so impressive. He’d missed what was going on in the north, for Christ’s sake. Still, I kept out of his way.

With him came twenty N.B.I. agents—men and women specially trained for this kind of thing. Before the Great Change, they’d have all carried big guns. These people, however, carried machetes, Tuareg-style swords called takoba, and high-tech bows and arrows, and were trained in hand-to-hand combat and wore weather gel–treated uniforms and army boots (you did not want to be near any of their feet when they took those boots off). Two women even had a pair of those Ginen weapons called seed shooters.

My friend Ejii had told me about these, but I’d never seen one until one of these women showed me. They look like hand-sized greenish brown disks with a notch on the side for your fingers. And they were very light. The woman, her name was Nusrat, clasped it in her hand as she faced the desert, the end of her brown veil over her head fluttering in the breeze. The other woman, Hira, wore a veil over her head, too. I assume they were both Muslim. Or maybe they just liked the attire; you never know.

Nusrat grinned, obviously enjoying demonstrating.

“It feels hard but it’s alive, a plant,” she said. Her voice was kind of low. If it weren’t for the enormous size of her chest (you couldn’t miss it, even with the uniform) and her face (okay, she was quite attractive), I’d have speculated that she might have been a man. She had an intensity that reminded me of Gambo, and there’s nothing remotely feminine about Gambo.

Nusrat took my hand and held it to the seed shooter. As soon as my hand touched it, it changed from greenish brown to dark brown as if it were some sort of plant chameleon. “It responds to touch,” she said, laughing. “It doesn’t like you. For some reason, seed shooters prefer women. The accuracy is always better when they are used by them. Be very afraid if you come across a man with one, especially if you’re not his target.”

I frowned, thinking of those giant flightless birds Ejii had ridden in Ginen. They supposedly didn’t let boys or men ride on them, either. Maybe things from Ginen preferred female humans to male ones.

“You stroke the side and it hums,” Nusrat said, rubbing the seed shooter. It made this

sound that was oddly like the purr of a cat. You could feel it, too. Like it was more animal than plant. I’d have thrown the thing away, but I wanted to know what it felt like when it shot. “When you squeeze it,” she said, “your four fingers have to be touching this smooth patch on the front.”

She pointed the seed shooter at the ground, aiming a few yards away, and squeezed my hand. I barely felt or heard a thing. Just a soft phht as something reddish orange blasted into the sand. Then there was a sort of oatmeally smell. POW! There was a small explosion in the sand as the seed popped like a large popcorn kernel. Some big green beetles emerged from the sand nearby and frantically scrambled away. Imagine what that seed would have done if the seed were embedded in someone’s chest, leg, arm, or . . . head.

She strapped the thing against the bare skin of her side, pulling her uniform over it. Seed shooters produce more seeds by feeding on body heat. Needless to say, those two women were probably the most lethal N.B.I. agents in the Sahara because of their skill and those weapons.

I smiled. Lethal was what I wanted.

• • •

Long ago, people used to talk about Blood Oil and Blood Diamonds. They should have been talking about Blood Chocolate, too. All those children. All branded with those tattoos their first day there. Applied by some hairy motherless man who reeked of alcohol and chocolate, with his cruel relentless dirty needle.

A blue line from the center of the forehead, down the bridge of the nose. All the way to the nose tip. Blue dots on the side of the line, like some weird railroad track. Imagine it. You’re ten years old or nine or fourteen or sixteen. And this is happening to you. On your face! To always be the first thing people see. And no one will come to stop it. No one cares.

I was one of those cocoa farm slaves. I have the facial tattoos to prove it.

We were all friends because we had to be. When you’re in a bad situation, you stick together. Well, at least until it is time to get the hell out. I’d still be there if I hadn’t thought like this. The only person who would

have come with me was dead.

When I returned to those farms with Buji, Gambo, and the N.B.I., it had been a year since my escape. Just seeing the place made my stomach growl with hunger and my heart clench with rage.

• • •

When I was a slave, I knew all the children around me. Asibi was about thirteen years old, like me. We used to bicker a lot because she never wanted to ever cross the masters, and I did . . . well, my close friend Adam did and his ideas were contagious to me. Asibi just wanted to survive. This always annoyed the hell out of me. One doesn’t survive by just surviving.

When Asibi was ten, she was walking home one day when a man approached her. He was all smiles and compliments, as those kinds of guys always are to those kinds of girls. He promised her that if she worked on the farms for a week, he’d pay her nine hundred dollars and give her a bicycle. She told me that that would have fed her family for three years and the bicycle would have allowed her to start her own business.

Asibi dreamed of selling dried butterflies. You know, those large yellow and red ones that cure colds when ground into a tea? That man didn’t tell her that she’d have to travel ten hours north in a sweltering empty old oil tanker infested with biting flies to get to the farm. Nor did her tell her that she’d almost die from heat stroke and dehydration on the way. And, naturally, he didn’t tell her that he was lying and that she’d never be going home.

Now, Tunde, Yemi, and Abiola were what we call “area boys.” They were about fifteen years old. They came all the way from Lagos, Nigeria. They’d sold drugs, stolen e-legbas, pacemakers, and hundreds of other electronic devices, extorted money from passersby, dabbled in the illegal trade of human organs, you get the picture. They were trouble and their stupid parents knew it. So, instead of being good parents and taking responsibility for Tunde, Yemi, and Abiola,

their parents sold them to slave buyers.

Halima, she was sold by her father for less than fifty dollars. Fiddausi was kidnapped, snatched right off the side of the road as she sold boiled eggs. Bako, Dauda, and Dogonyaro were the children of one of the slave masters! And the three of them worked as hard as anyone else and lived as hard, too! You can see how twisted the minds of the slave masters were. Hell, they made their own children slaves! It’s a cultural disease and it runs deep.

As we traveled back to the slave plantation, I remembered so many names. I remembered backs with wet festering sores and ugly scabs from whippings. Bent from heavy sacks of cocoa beans taller than them. Cracked lips. Bleeding fingers. Blank emotionless faces. My own story was a little more complicated. Actually, it wasn’t . . . like so many others, my parents sold me, too. They couldn’t deal with a son who kept getting struck by lightning and having the nerve to keep living through it. I embarrassed and humiliated them. Imagine that.

Oddly, I think I was the only Changed One there. The buyers stupidly didn’t notice my abilities. My uncle Segun who brought me there obviously kept that little fact quiet. He wanted his money, I guess.

Normally, the farm owners were smart to avoid buying and taking Changed children. Think of the trouble a windseeker, metalworker, sidewinder, sorter, or a shadow speaker could cause. Especially one who manifests strongly at a young age. Of course, one didn’t have to be Changed to shake things up. Look at my friend Adam. They feared him so much that they killed him.

Many of the slave children had never even tasted chocolate. There was a busybody girl named Zuumi. She was about nine years old. Really really smart but mischievous. We called her Zoom because she liked to keep a close eye on the masters. She could tell what they were up to even from far away. One day she saw one of the masters drop a candy bar in the sand. Those sick bastards enjoyed eating them in front of us. With their chocolaty breath, sticky hands, and violent tempers. I won’t call them what they really were.

They never saw Zoom creep up and snatch up the candy bar. We usually ate burned bananas and thin rice porridge and beans riddled with black beetles. That night in the shed that they always locked us in, she shared the melted chocolate bar. Everyone who wanted one got a fingertip

full. Fifty children had their first taste of chocolate that night. For this reason, the shed was noisier than usual. Those who’d tasted it whispered, snickered, giggled, and chatted for hours. I couldn’t care less. I’d tasted chocolate plenty of times. Heck, I was well versed in the taste of far more exquisite cuisine. But I was happy for the others. They deserved to taste what they were suffering to make.

Unfortunately, some kid leaked information about the chocolate bar to the masters. The next day, Zoom was dragged out and beaten unconscious. The Masters were so afraid we’d develop a taste for the stuff; that the chocolate would spark ideas of rebellion and freedom in our mouths that would travel to our souls. They had nothing to worry about. We were a broken bunch.

Except for Adam. And me, I guess. They killed Adam by letting him die when he got sick. I escaped. By the skin of my teeth.

• • •

The place had changed since my time there.

Earth’s lands rarely stay the same for long. It’s so alive and twisted. Desert can become ocean overnight. Mountain can become flatland. Jungle tends to just get bigger and wilder; rarely does it become desert. But desert certainly becomes jungle. And there is more of everything. More land. More worlds. The Great Merge made sure of that.

The miles of desert that once surrounded the farms, the deserts that had nearly killed me when I escaped, were now grassy savanna. It was populated with bony long-eared hares and small edible yams. Between the small pools of water, the hares, and the yams, a resourceful kid could easily survive an escape from the farms . . . well, if it weren’t for one thing. Something lived out there, in the dark. It tried to attack us that night. Some roaring, sniveling thing that no light could catch.

The ground shook as it moved. That’s what woke us all up. There was a lot of scrambling, as it was the dead of night. No moon. The stars blocked by thin clouds. I don’t sleep in tents, so I merely had to stand up. Kola, my owl, flew onto my shoulder.

The air was calm. Dead. And the night air was suddenly very very warm and dry. Night in the desert has never been warm in places like this. You could

hear the clang of takoba swords, bows and arrows, machetes, as people snatched for them. I heard Agent Ali bark out orders in his unsmiling voice. But I was looking into the night, past our camp. Like any rainmaker, I could feel it more than see it. About a half mile away, the air wasn’t right. It wasn’t right at all.

“A man at that market told us about this,” Gambo said, stepping up beside me. He smelled of sandalwood and his white garments were swirling around him. “I didn’t believe him.”

“I did,” Buji said, calmly.

I think both Gambo and Buji were smiling. But it was dark and so were they, so I couldn’t be sure. Those two always had a thirst for a good fight. Not me, though. No warrior blood in my veins.

“Told you about what?” I whispered. The ground shook again.

“Follow my lead,” was all Gambo said. “The others can’t do anything about this. Just you and me, Dikéogu.” God, sometimes he could be so cryptic.

He quickly moved forward. Instinct told me to run backward. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...