Chapter One

My shoes scratch against the uneven pavement, and I know right away that they’ve been scuffed real bad. I immediately think of my mom—I pretty much begged her to buy these shoes for me. “Take it out of my college fund or something,” I told her, like an idiot, and she laughed in that stiff way she does whenever we talk about money. If she sees them scuffed up so early, I’ll never hear the end of it. I’ll never hear the end of the shoes, the same way I’ll never hear the end of this—this bra thing. I gotta tell Kate.

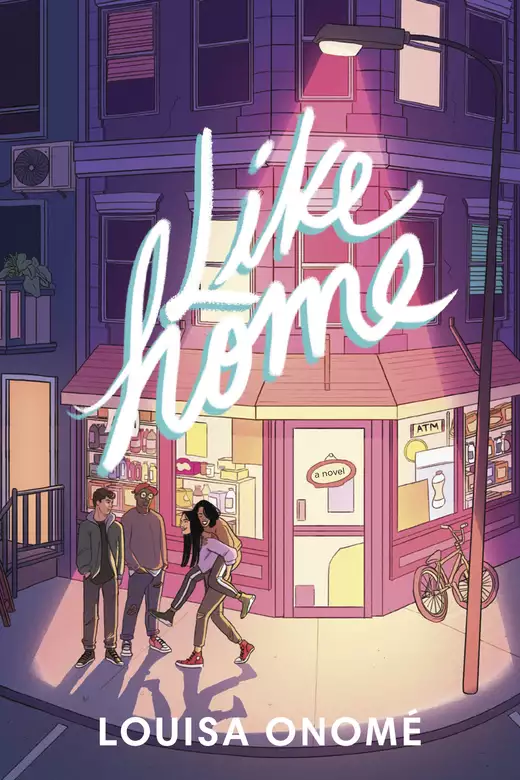

It is April, and Ginger East is quiet early in the morning, so my light footsteps sound like heavy boots as I run. The sun creeps over the top of the highest building on the main road, casting stale light on dusty storefronts and barely swept roads. A set of duplexes that used to be cash-and-carry outlets stares back at me as I reach the end of my street, Ginger Way. Mom used to buy fish and bedding from there. Two different departments, same store. They moved out a long time ago. Now it’s a coffee place open bright and early at seven a.m. Man, the only people up this early in Ginger East are us schoolkids who need to catch a bus, the few homeless people who live in that shed behind the liquor store, and the Trans—Kate and her family—because they run Ginger Store.

My feet slow as I round the corner approaching Ginger Store, and then stop as I pull open the door. It’s hard to get in with how the wind seems to be pushing at it. Mrs. Tran is at the register and immediately leans past the counter to see who it is.

She frantically waves at me and says, “Chinelo? Shut the door, please.”

I do as I’m told, and the fierce wind tunnel dies. My carefully straightened hair, which I tried so hard to smooth down this morning, is frizzing around my shoulders. “The back door is open,” she says, settling onto her stool behind the counter again. “Kate’s dad is mopping the storage room, and with all the doors open—whoosh,” she explains, waving her hands around to symbolize the movement of air.

“Why doesn’t he tell Jake to do it?” I ask. Jake is Kate’s useless older brother who’s gotten away with doing the absolute least because he’s a boy. He’ll straighten one shelf and complain for hours. He outgrew his cool-older-brother phase ages ago.

Mrs. Tran makes a face like she knows her son is useless and why would she even consider asking him? I laugh, a difficult feat after sprinting all the way here, and ask, “What about Kate?”

The sound of a freezer slamming in the back rings out, and then I notice Kate trudging up the middle aisle, her arms extended in front of her. Her lips are curled into a pout as she approaches, her stark dark hair gathered messily around her neck. “How many things do you want me to do in one morning? Like, damn.” She grunts, shaking her hands.

I look at her fingers, because I feel her eyes are urging me to. They just look dry. “What’s your problem?”

She ignores me and takes a slow step toward her mom at the counter. “Mom, my hands are fro-zen. Can’t I organize the ice cream after school? No one’s out here buying ice cream before noon.”

Her mom frowns all strict. Mrs. Tran is definitely the nicest Tran, so the small tic between her eyebrows really strikes fear into my scuffed-shoed feet. I loop my arm with Kate’s instantly, saying, “I’ll help you.”

“See?” Mrs. Tran cuts in with a wry smile. “Nelo is a good worker.”

Kate’s mouth drops open. “Worker? But you’re not even paying her, though. You’re not even paying me—”

“Ah, so I should pay you to live in my house?”

I snort. My mom and Mrs. Tran are pretty much the same person at this point. They probably share insults on some group chat called Neighborhood Moms. “Come on,” I say to Kate, tugging her down the aisle.

From where we disappear to, I can hear Mr. Tran sloshing a mop across the linoleum tile in the hallway. Even so, the smell of chocolate is strong back here. Ever since that hot-chocolate-machine explosion incident when we were nine, the store has smelled like chocolate—and old building and cardboard and musty floor wax.

Kate shimmies free of my grasp as soon as we’re hidden. She gives me a knowing look and says, “I got you,” before dipping into the freezer for a Vita ice cream bar. It’s seven a.m., but I don’t argue. I snatch it from her, peel off its wrapper, and stuff it into my mouth as if it was made for me. She tries not to cackle. “You’re so extra!”

“I love these,” I say through a cold mouthful. Vita ice cream is the best ice cream, my absolute favorite. Ginger Store is the only place around here that sells it, and every time I eat it, it reminds me of some of the best times I’ve ever had.

Usually, in the summer, my friends and I used to meet up here and buy ice cream. Sitting at the curb by the storefront, watching customers come and go amid the humidity and heat. We were all about the stickiness of sunrise-to-sundown adventures and the cool, calming wave brought on by tubs and tubs of ice cream. Nothing really has come close ever since.

Life split us up. I guess that’s normal, but it still sucks. Our friends moved to a nicer neighborhood closer to school. It’s only Kate and me who live on Ginger Way and who still talk about summers with too much ice cream. A small part of me feels it’s a matter of time before she leaves too, but I know the Trans, and they wouldn’t leave. Ginger Store is as much the neighborhood’s as it is theirs, so they’d never sell. So many businesses have come and gone around here, cash-and-carries turned into hair salons turned into loan offices, but Ginger Store is a staple. Ginger East would be nothing without it, but if I’m being honest, maybe I’d be nothing without it too.

Kate purses her lips, biting back another laugh. Then she points a stern finger at me and says, “Do not say anything to my mom. She’s doing inventory.”

“Uh, why would I?”

“You and my mom are obviously like this,” she says, crossing her fingers.

I snort, say “Shut up,” and punch her in the arm as lightly as I can. I barely feel her thick sweater on my knuckles, so I punch her again, but this time deeper. She gasps and returns the favor, except she misses my arm by an inch and her knuckles land square on my left tit.

Her face says it all. Her mouth makes a perfect O, and her brows arch so high, they almost meet her hairline. I instinctively bring a hand to shield my chest in case she does it again. And she does, but this time she leans forward, tipping the top of my animal-print sweater so she can see down my shirt. When I try to swat her away, she takes a step back and gapes even wider. She whispers, “Are you, like, padding your bra now?”

My face is burning up under the store lights and her growing shock. Her eyes—she’s watching me so hard! “No! Why would I?”

“Then what . . . ?” she asks, letting her eyes drop to my heavily sweatered chest.

I take a second and cast a quick look over my shoulder through the store. Everything is undisturbed. The aisles of food, scissors, telephones—you know, corner-shop stuff. Mrs. Tran’s shelf of used books stares back at me from the wall. The lotion that’s mad scented when you apply it but then dies after an hour is untouched on the counter. It’s quiet and safe enough for me to turn back around and whisper to Kate: “Okay, so this morning my mom comes to me, right, and peeks down my shirt, and was like, ‘Chi-chi—’ ”

“Who’s that?”

“Me.”

Kate screws up her face with disbelief. “Since when?” Exactly! Even she knows that no one has ever called me that.

“I don’t know. Mom just started calling me that one day, maybe literally the day Dad left to go to Calgary for work. She’d never call me that if he was here.” There’s a Chi-chi in every Nigerian Igbo family, and I don’t know why my mom is trying to turn me into Chi-chi when I already have a cousin who claimed the name.

“It doesn’t suit you.”

“That’s what I’m saying! And she was like, ‘Chi-chi, we need to think about getting you a bigger bra.’ If you heard how she enunciated ‘bra.’ And I was like, I mean, I didn’t even say nothing. Just ran. How awkward is that?”

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved