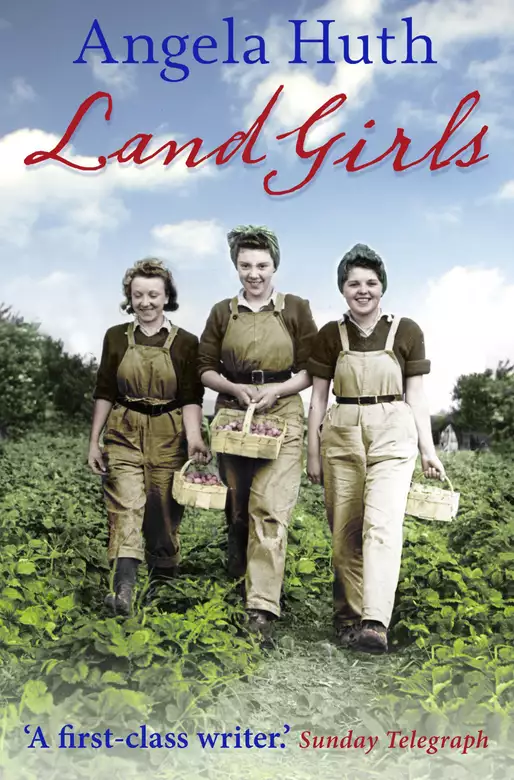

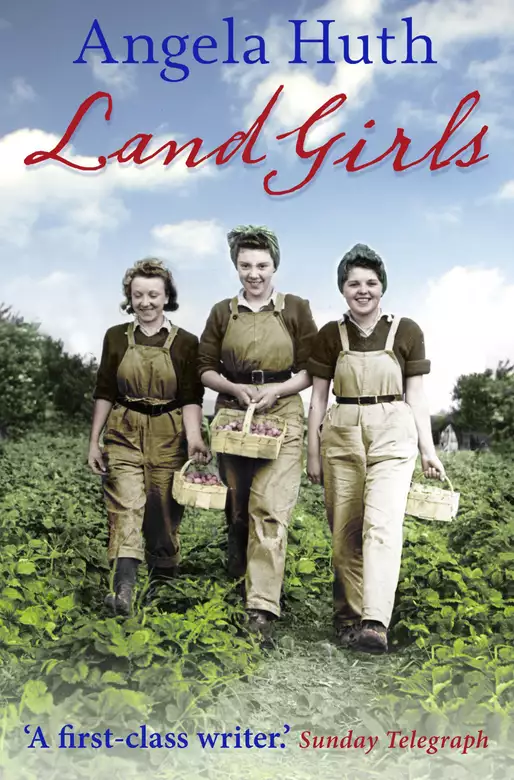

Land Girls

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

With the country's men at war, it falls to the land girls to pitch in and do their bit... Stella arrives at Hallows Farm in her Rayon stockings, having just waved goodbye to the love of life - naval officer Philip. Agatha has just graduated from Cambridge; life on the Farm is certainly going to offer her a different kind of education. Prue, a hairdresser from Manchester, is used to painting the town red, not manual labour. Joe dreams of leaving the family farm and becoming a fighter pilot. But with the arrival of these three beautiful young women, there's enough to keep him busy on the farm for the time being... Work is hard and the effects of war start to take their toll on the three women. But as the bonds of friendship start to form and excitement builds as the RAF dance looms, maybe life in the countryside isn't so bad after all?

Release date: February 2, 2012

Publisher: Constable

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Land Girls

Angela Huth

Agatha saw Prue pause, flutter, not daring to look down. Her left foot wavered, suddenly unsure where to land. The toes panicked. She was nearly at the end, where a ladder waited. But she could not make it.

Agatha saw Prue fall into the darkness, heard her scream. No one in the house could have heard, because at that moment a siren began to wail. Its mournful voice and the ragged shriek coiled into a terrible sound that, even now, some fifty years later, Agatha still heard.

With an effort she withdrew from the picture of that night, and returned to her place at a prim restaurant table in a London hotel.

Agatha was the first to arrive, as always. Stella could never be on time. Prue was unpredictable.

She pulled off a slither of black kid glove and let her finger run over the whiteness of tablecloth that radiated before her. She hoped the nearby waiter, officiously observant, would not present her with the enormous menu poised in his hand nor make enquiries as to her desire for a drink. She did not want anything, except a few moments to gather herself before the others arrived. It had been a long journey from Tiverton, and her grandson Joshua had driven through the London traffic too fast for her liking. She felt a little ungrounded. Cities always filled her with unease. She was glad she had refused her daughter’s invitation to stay the night, and had decided to return on the five o’clock train. Her husband would be at the station to drive her home. He would have lit the fire and put the pie in the oven as instructed. In old age, she relished the safety of their quiet evenings together. There were few occasions for which she would sacrifice one of them for a night in London. She came up rarely, now, though nothing but real disaster would keep her from the annual meetings with her oldest friends.

When she looked up she saw that the waiter had turned his back. He had probably decided an old lady, peacefully waiting, was not worth approaching. Quite right. Agatha knew the usefulness of her stern look, and she was glad she had employed it. The professor had married her, he always said, because she was so alarming. He had wanted to know whether, over the years, he would grow less alarmed by her. Had he? She didn’t know. It was not a question she could ever ask.

Outside the window, the trees of Hyde Park were more thickly gold than the trees in Devon. Their own beech had only just begun to turn. She remembered that frivolous park trees were always far ahead in their maturing. This she had observed so many times while waiting for the others. It was a wonder the amazement remained. And the trees, of course, were the reason they had chosen this place originally. As ex-land girls, all of them, they wanted to be able to see the sky while they were eating. They had had their first reunion lunch in this very dining-room just after the war, a few months before Prue’s wedding. Terrible food – corned beef and boiled potatoes – but none of them had minded. Some years later they had experienced their first avocado together – a table in the corner, if Agatha remembered rightly. It had been exciting, that first slipping of silver spoons into the creamy green flesh of an unknown fruit. That was the year, Agatha recalled, when the lunch had started more easily than usual – all laughing over their reactions to the avocado. They had felt none of the initial awkwardness that overcame them on re-meeting after a gap of a year or more. They lived so far apart, their lives had taken such different directions – it was difficult, sometimes, to know where to begin.

Agatha’s fingers, calmer now, slid up the thin silver flute of the flower vase. It held a single pallid rose and a wisp of fern. She tried to work out how many times the three of them had contemplated each other’s metamorphosis over similar, scant little flower arrangements. But what did it matter, how many times? It was a tradition that would go on till one of them died. Then, would the remaining two …? When one of them died, would the remaining two consider it loyal or disloyal to continue the lunches?

Agatha looked up. She saw Prue in double image – young and high on the beam but, more sharply, a tiny figure dwarfed by the great door of the dining-room, alert little head pecking round the tables in search of her friend. Agatha waved her glove. Prue smiled, pursed her bow lips. She hurried over with such speed that waiters, poised to offer their assistance, saw any help would be redundant and stepped back with secret smiles. They were used, Agatha supposed, to eccentric old ladies.

When Prue reached the table, Agatha stood up. They bent towards each other, making a triangle over the rose. They kissed. Prue smelt of the exotic, musky scent she had always worn: Stella and Agatha had never been able to approve. She was dressed in green, as usual, to match her eyes. A velvet beret slumped fashionably over one side of her forehead, half hiding the white fringe. In the past the fringe had been very long – a cause of constant complaint – and blonde. From under it she would flutter those down-turned eyes at any man who came into the farmyard, in imitation of the glamorous film stars whose lives she found so fascinating. The eyes were still an extraordinary green. It was hard to imagine that Prue, the youngest of them, must be nearly seventy. Whereas she, Ag …

‘You look just the same, Ag. How are you?’

‘In pretty good spirits.’

They sat down, both fiddled with their stiff napkins, veered their eyes from each other lest further scrutiny reveal changes they had no wish to see.

‘Sorry I’ve kept you waiting. Manchester train’s not usually late. Still, I’ve beaten Stella.’

‘I had a postcard from her only last week saying she’d be catching the eight fifteen from York.’

‘So did I.’

‘Did she mention her health?’

‘Only to say there’d been another attack of bronchitis.’

‘She wrote the same to both of us, then.’

‘She always does.’

‘She always had such an innate sense of fairness, dear Stella.’

‘So fair, yes.’

‘That time – that harvest time.’

‘That harvest! I often think of that.’

They paused. Agatha was fingering the damask cloth again, while Prue ran a pink nail up the stem of her wine-glass. A nearby waiter, seeing his chance, was upon them in a trice.

‘And would the ladies care for an aperitif?’

Agatha put on her fiercest face. She didn’t care for the way waiters addressed people these days.

‘You’ll be having your usual White Lady, Prue?’

‘Why not?’ Prue twinkled.

‘And I’ll have a Kir Royale.’ Then, in a voice so low the waiter was denied the private information, she added: ‘Something Joshua introduced me to last Christmas.’

‘Joshua!’ Prue, who had no grandchildren, clapped her hands. Agatha had always admired her enthusiastic interest in other people’s relations. ‘He must be thirty?’

‘Almost,’ said Agatha.

But she was not thinking about Joshua. She was thinking about her husband: at this moment he would be sitting with his cheese sandwich by the Aga, preoccupied by the future of his Friesians. Alone, without her there to deflect his thoughts, he would be worrying once more about whether they would have to sell up the farm. Agatha dreaded his decision. They did not want to move, after forty years.

‘So?’ said Prue, when the waiter had gone off with the order.

‘So,’ said Agatha.

The very thought of having to distil her news made her curiously tired. The friends had not met for eighteen months, though they had kept in touch with occasional letters and cards. In that time nothing exciting had happened to Agatha: probably nothing very much exciting had happened to the other two, either. But having made the effort to travel so far to see one another, each felt it incumbent upon her to do her best to entertain. What usually happened was that they found themselves racing through contemporary news with perfunctory speed. However much they intended to convey to the others the nature of their present lives, what really fired them was their past. To reminisce was so much easier – the jokes that never dulled, the intriguing speculation about what might have happened, the realization of what the hard years of the war had taught them. Prue and Stella and Agatha never ceased to marvel at the powerful warmth that still emanated from a shared experience of so many years ago. They would leave their meetings reinvigorated: newly grateful that something that had bound them in the past could remain so benevolently alive, untouched by the vicissitudes of the intervening years.

Agatha and Prue glanced at each other with a feathery shyness that would soon be dissipated by their cocktails. They had a mutual need of their friend to enliven this reunion. Stella, who was always the best one at breaking the ice. Stella, who used to say she could not imagine living without being in love – it would be a wasted day, a day not loving someone, she used to say. Stella, who, as Agatha had recognized the moment she met her, was blessed with the kind of exuberance for daily life that could accommodate other people’s awkwardness. Agatha had learned so much from Stella.

‘She’ll be here any minute, I expect,’ she said, a little desperate, longing for her drink, and longing even more for the train journey home when she could dwell on all that was about to be said.

‘Of course she will. Dear Stella,’ said Prue, also a little desperate, and flashing her green eyes in what Agatha recognized as a familiar, hopeful fashion towards the door.

On an evening in early October, 1941, John Lawrence drove the three land girls home from the station.

It was unusually cold for the time of year. There had been a hard frost that morning which had not melted all day. Frozen puddles spat at the wheels of his cumbersome old Wolseley. He could hear the angry hiss and crackle as the ice splintered. The noise reminded him of those small fireworks that he had waved round in his hand, on bonfire night, to please Joe when he was a child. He kept his eyes on the road.

There were two girls in the back, one by his side. Faith had told him their names several times, but he remembered none of them. At the station, he hadn’t liked to ask. He had shaken hands, introduced himself, and picked up their suitcases before they could protest. They looked a nice enough lot, far as he could tell. The district commissioner had guaranteed she would send some good ones.

But good or not, Mr Lawrence was unhappy about the arrangement. He knew nothing about girls, didn’t much like what he’d heard. He and Faith had married at eighteen, two months before the 1914 war was declared. Faith had managed on her own, somehow, for the four years he was away. She had never complained, in her wonderful letters, about the cold and meagre cottage, the poverty, the giving birth to Joe alone by a small fire. When Mr Lawrence came back alive, unwounded, she said they must never part again. They never had: they never would. She was the only woman in his life. He could not imagine another one. He was glad they had no daughters.

It had taken him some time to be persuaded about this land girl business. But his two farmhands had been called up within weeks of the outbreak of the new war, and it was clear he and Joe could not physically cope with the farm on their own. They worked a sixteen-hour day and still things were left undone. Why not try this Land Army plan, Faith had said, as one who read every word of the newspaper on the days someone brought one to the house, and knew all about the scheme. If it didn’t work, she said, they could think again. With an acute shortage of men in the whole neighbourhood, Mr Lawrence was forced to agree there was no alternative. He had conceded with reluctance.

Now, here they were, the three of them, in his car. Very quiet, not a word between them. Mr Lawrence sniffed. The pungent smell of wet collie, which had eaten its way into the fabric of the car years ago, was pierced by a new, high-pitched feminine smell, the kind of thing Faith would call exotic. Disgusting, in his opinion. Already an invasion into his car, where he liked to be alone with his dogs and their rightful smell. He rubbed his nose in protest. The girl beside him stiffened. He could see from the corner of his eye that she had turned her head to look out of the side window. Slowing down, he took this opportunity to glance at other parts of her: prim little gloved hands folded on her lap, skirt made of a pinkish fuzzy stuff. Her legs were crossed, just one knee visible. The small, square plane of knee bone strained against the bronzish fibre of a stocking. As Mr Lawrence looked, fascinated, a streak of light broke through the grey cloud, flared through the windscreen. For an infinitesimal moment the knee bone dazzled like a jewel. Mr Lawrence withdrew his eyes. Rayon stockings! That was it. Faith only had one pair, for church. Well, this young lady would soon learn there was little time or place for rayon stockings on the farm. Already he could not like her. She’d be all over the house with her blessed stockings, hanging them up in the bathroom to dry if he wasn’t careful – he could see it all. Total invasion.

‘And what’s your name?’ he asked.

‘Stella.’

Stella! Christ. He might have known she’d have a fancy name. He determined not to ask the others. The names would come to him in time. If he gave them time, that was.

He adjusted the mirror, glanced at the passengers in the back seat. Two blurred little faces, spotted and clouded by the imperfections of the glass. One of them had a long pale fringe that covered most of her strange-looking cat’s eyes, greenish as far as Mr Lawrence could tell. She wore more lipstick than Clara Bow. Obviously saw herself as a film star: he’d enjoy seeing her scrape the shit off a cow’s backside, he would. The thought made him smile. The other one struck him as more schoolmistressy, prim. Dark bobbed hair, pale skin, nothing on her lips. What a trio, he thought. With them in the house … still, he’d give them a chance. He was a fair man. He could be wrong.

‘Just half a mile to go, now,’ he said. He felt a general shifting in the car. ‘This is where my land starts, on the left. You’ll be working the fields up here.’

A turning of heads. A swing of blonde curls reflected in the freckled mirror. Curious widening of green eyes. He wondered how they saw his neatly trimmed hedges – a master hedger himself, they would never believe how many man hours the job took him, and what satisfaction it gave him. He wondered how they saw his nicely harvested fields, the yellowing woods on the rising distant land. Did it seem wild to them? Alarming? Faith had said none of them was a country girl. Somewhere as remote as Hallows Farm would seem very strange.

He swung the huge steering wheel. The Wolseley lurched through an open gate, throwing the dark girl up against the fair one. Slight nervous giggles. Apologies. He slowed down through the farmyard, came to a halt near the house. When he had switched off the engine, he returned his hands to the steering wheel. It crossed his mind that he should attempt a smile and say, Well, here we are, girls, in a voice of welcome. But he decided against it. He was not a man accustomed to stating the obvious, and lack of histrionic talent meant he could not disguise the foreboding he felt. On the other hand, he had no wish to be unfriendly, and the girls must be puzzled by his long silence.

‘This is it,’ he said at last. ‘I’ll hand you over to my wife, Faith.’

God, how he longed to hand them over.

The girls clambered out of the car. Mr Lawrence saw them scanning the ground, each one silently planning her route through seams of mud that had spilt through the frost. While he unloaded their cases from the boot, he watched them skitter from patch to patch of hard, silvered gravel, protecting their fine little shoes from the spewing mud. The tallest one, the dark one, seemed to be the most skilful on her feet. The pink skirt was hesitant, delicate; the film star teetered and giggled and almost fell. They looked like an unrehearsed chorus line, Mr Lawrence thought: bright banners of colour – pink, green, pale blue, so odd against the dour stone façade of the house. They reminded him of flowers.

One of Faith’s neurotic birds came squawking round the corner.

‘Look! Have you ever seen such a small chicken?’ squealed the film star in a broad northern accent.

The tall dark girl bent down over the bird, as if to stroke its frantic head. ‘I think you’ll find it’s a bantam,’ she said.

Faith appeared in the doorway of the porch. Her eyes met her husband’s, then sped from pink to green to blue, uncritical.

‘I’m so glad you’re here,’ she said. ‘You must be ravenous and tired. Come in, come in.’

Mr Lawrence watched the coloured banners march through the dark doorway to begin their invasion.

The girls followed Mrs Lawrence into the kitchen. Prue was last in the line, silently smarting at the snub by the snooty dark girl. How was she supposed to know a bloody bantam from a hen? There had been no instruction on the subject of poultry at the training course, and the only birds she saw in Manchester were hanging upside down and naked at the butcher’s.

The kitchen was large, dim, steamy, billowing with a warm mushy smell of cooking, a smell Prue could not quite place. The pale flagstone floor was worn into dimples in front of the enamel sink. On the huge spaces of the dun-coloured walls, scarred with flaking paint, the only decoration was a calendar, dated 1914. Its faded picture was of a young soldier kissing a girl in front of a pretty cottage. Farewell was the caption, in copperplate of ghostly sepia. Prue felt her eyes scorch with tears. She longed for the small box of a kitchen at home, the shining white walls and smell of Jeyes Fluid, and the shelf of brightly coloured biscuit tins her mother had collected from seaside towns. This place was so horribly old-fashioned, gloomy, dingy. And the two collies lying on a rag rug in front of the stove looked dangerous. Prue hated dogs. She turned to look out of the window so that the others should not see her tears. But the view was smeared with condensation. All she could see was the indistinct hulk of a barn or outbuilding, and the slash of darkening sky.

The characteristics of a hard-working farm kitchen that so distressed Prue left Stella unmoved. In her dreamy state, having left Philip only twenty-four hours ago (Philip whom she loved with her whole being, Philip for whom she trembled and sighed and longed with a pain like hot wire that strangled her gizzards – the simile had come to her in the train), she was indifferent to all external things. She knew that in automatic response to her disciplined childhood, and the four weeks’ training course she had enjoyed, a sense of duty would ensure she worked efficiently. She would not let her mother down, and would willingly do whatever was required. On the other hand, she would not be there. Her soul would be with Philip as he boarded ship at Plymouth, so meltingly beautiful in his uniform that the very thought of that stiff collar cutting into his neck filled her with glorious weakness. And in the impatient weeks waiting for his first letter her mind would feed on the memories she had of him, rerunning the pictures over and over again. She would never tire of them. The best, of course, was Philip at her birthday party, removing his jacket, despite her father’s disapproving look. It was too hot to waltz in comfort, he had said. That waltz! Their skill at dancing had been hampered by their mutual need to be joined at the hip bones. Exactly the same height, they had found the need increased – breast bones, chins, a scraping of cheeks, a clash of racing hearts becoming clamped together. By the time the music had slowed they weren’t dancing at all, merely rocking gently, oblivious to everything but their extraordinary desire.

‘Jellies are now served in the dining-room,’ her mother had shrieked, ‘and there’s plenty more fruit cup.’

Stella and Philip had not wanted jellies: they’d wanted each other. They’d slid from the room and raced upstairs towards the old nursery. It housed a large and comfortable sofa, useful to Stella on several passionate occasions in the past. She had shut the door behind them. Blackout was nailed to the window frames, the darkness unchipped by any glimmer of light. Stella had taken Philip’s hand and guided him past the rocking horse, giving it a wide berth: one of her suitors had bruised his leg so badly that kisses had been interrupted by howls of passion-quelling pain. They reached the sofa. Blindness added to the excitement. She had felt him sit next to her and wondered impatiently why he was fiddling with his sleeve.

‘What are you doing?’

‘Taking out my cufflinks.’

‘Why are you taking out your cufflinks?’

‘I want to roll up my sleeves.’

‘Why do you want to roll up your sleeves?’

‘I always roll up my sleeves, that’s why.’

‘Rather as if you were getting down to gardening, or something?’ Stella giggled.

‘That sort of thing.’ It didn’t sound as if he was smiling.

Philip had pushed her back on to the sofa. As his mouth splodged down on to hers (in the blackness she suddenly forgot what it looked like, but tasted sausage roll and beer) she felt him expertly flick up the skirt of the sophisticated dress that old Mrs Martin had made from a Vogue pattern. As Philip’s finger had run up the back of her leg, following the line of her stocking seam till he reached the stocking top, Stella realized Mrs Martin was the only person she actually knew who had been killed by a bomb. The finger continued its journey over the small bumps of suspender – not to object to a man’s acquaintance with her suspenders was surely a sign of real love, she thought – and by the time he had reached the leg of her knickers, all sympathy for Mrs Martin had fled. Stella had heard herself moaning, and felt herself squirming in a way which could have been embarrassing had she been visible, but in such utter darkness anything seemed permissible. Then, as Philip employed a second efficient finger to part the way, the warning siren had wailed through the room. They disentangled themselves, made their way back through the blackness, whispers lost in the siren’s moan. The music had stopped. Shouts of instruction came from downstairs. Stella remembered feeling very cold.

If it hadn’t been for the siren, what might they have done?

Crowded into the wine cellar with the other guests, Stella had watched Philip roll down his shirtsleeves and put back his cufflinks. He’d whispered to her that it had been a damn shame, the interruption.

‘But my first shore leave, I promise …’

‘Promise what?’

‘You know what. We must be patient.’

Stella had felt the tremor of his impatient sigh. They’d held hot hands.

‘How can we be patient?’

‘We can’t. But I love you. What a place to have to tell a girl.’ He looked terribly sad. Stella took his other hand.

‘Say it again and again and again so I believe it.’

‘I love you.’

‘Well, I love you too. Listen: that’s the all clear.’

‘That was quick. Thank God no bombs.’

The guests had shuffled back upstairs, but the party was clearly over. Philip had kissed Stella goodbye at the front door. Then he’d left her in such a deliquescent state of love that today’s journey had brushed past her like ribbons. She’d had the sensation of not moving, though finding herself in trains, in cars, landscape flowing by her.

But she was standing still at last. Things had stopped rocking and swaying. Reality imposed itself more sharply. She could focus again, focus on the large expanse of scratched but clean blue oilcloth that covered the kitchen table, the four white mugs fit for a giant’s kitchen, a mahogany-coloured teapot big enough to house several Mad Hatters, the matching jug filled with creamy milk that frothed like cow parsley.

Stella raised her eyes to her new employer’s wife and wondered if Mrs Lawrence could see the state of her tangible love. Mrs Lawrence gave the slightest nod, and bent to wipe the immaculate oilcloth with a clump of grey rag. This small acknowledgement was enough for Stella. She was instantly drawn to the gaunt, bony woman with her cross-over apron, sinewy forearms, ugly hands, and grey hair rolled so high round the back of her neck the vulnerable hollows between the tendons were cruelly revealed. Stella liked her flint-head face, its slightly protruding jaw, sharp nose, wrinkled lids over dark brown eyes. She admired the beige flesh scored by years of hard physical labour. She looked down at her own unsullied hands, nails buffed to a luminescence that was apparent even in the dusk-grained light of the room. She felt a sense of guilt at her own easy life.

Mrs Lawrence was pouring thick noisy tea into the first mug.

‘I must get you straight,’ she was saying. ‘Which of you is …?’ She glanced at Stella, who felt the honour of being chosen first to reveal herself.

‘I’m Stella Sherwood.’ The breathiness of her voice was a private message to Mrs Lawrence.

‘And you?’

‘Prue Lumley.’

‘Prue. So you must be Agatha?’

‘Yes, but please call me Ag. Everybody does. Nobody calls me Agatha.’

‘I wouldn’t think they would, would they?’ said Prue, still smarting from the incident of the bantam.

Mrs Lawrence handed the girls the mugs of dark tea, told them to help themselves to bread and butter: she had arranged thick slices on a plate. Prue, suffering withdrawal symptoms on her first day for years without a chocolate biscuit, scanned the dresser. All she could see was a rusty old bread bin. She thought Mrs Lawrence was pretty odd, not offering them biscuits after their long journeys.

‘When we eat this evening my husband will explain the plan of duties,’ Mrs Lawrence said. ‘We eat at six thirty. I’ll take you upstairs, let you unpack, settle in.’ She paused, gathered herself to break difficult news. ‘I hope you don’t mind all sharing a room. We only have two small spare rooms, so one of you would have had to board in the village. I thought you’d rather be together … so I set to work on our attic, a lot of unused space. It’s nothing very luxurious, but it’s clean and comfortable. In the evening you’re at liberty to sit in the front room with us, of course. We have the wireless on, and the wood fire. It can get quite snug in there.’ She paused again, braced herself for another difficult announcement. ‘All I would ask is that you don’t try to engage my husband in conversation in the evening. He’s exhausted after his day. He likes to listen to the news with his eyes shut … You could always bring down your darning, the light’s better than in the attic.’

Darning? Stella and Ag looked from Prue’s appalled face to one another.

Their mugs of tea finished – in Stella’s case only half finished – the girls followed Mrs Lawrence. The stairs were covered in antique linoleum, and led to a single passage with walls of stained wood. Its old floorboards, spongy beneath their feet, hollowed as if they had been carved, were covered by a strip of carpet worn to its ribs of fibre. The passage led to a bathroom similar to Prue’s in Manchester only in its small size. As she gazed at cracked tiles, the tail of rust from taps to plug in the bath, the scant mat on the linoleum floor, Prue was overwhelmed by the memory of fluffy pink bath towels and the crocheted hat which covered the lavatory paper at home. She felt tears rising again.

‘We all have to share this,’ said Mrs Lawrence, ‘but it can be done. Two baths a week, evening if you don’t mind, and easy on the water. Three inches, my husband says. Four if you cut it down to one a week. And please remember to clean the bath before you leave, and keep your towels upstairs. We’ll be through by four forty-five, so you can fight to wash your faces after that.’

Four forty-five a.m.? In her astonishment, the comforting thought of the pinks of home faded from Prue’s mind. Mrs Lawrence, sinewy arms folded under a flat chest, led them up a steeper, narrower staircase to the low door of the attic room.

It stretched the length of the house, a sloping roof on one side, with three dormer windows. The exposed beams had recently been limewashed: there were spots of white on the scrubbed floorboards and the few old rugs. Ag, with her observing eye, immediately appreciated how hard Mrs Lawrence must have worked to achieve such sparkling cleanness. As one who had spent five years in spartan boarding schools, it was all wonderfully familiar to her: the narrow iron bedsteads with their concave mattresses and cotton bed-spreads – these, Ag guessed, must have begun their days as dustsheets. She took in the marble-topped washstand with its severe white china bowl and jug, the two battered chests of drawers, the lights with their pleated paper s

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...