- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

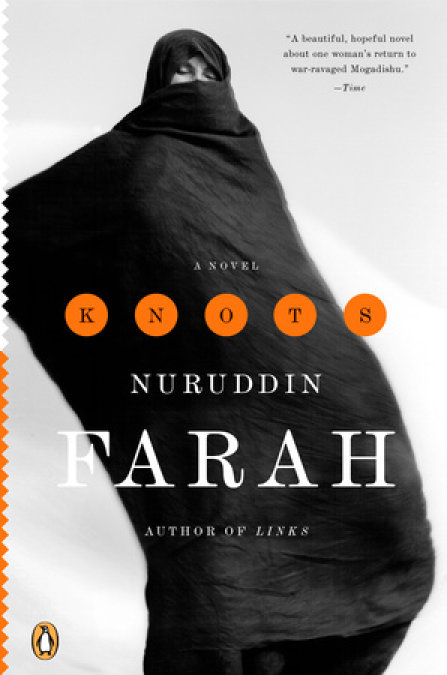

From the internationally acclaimed author of North of Dawn comes "a beautiful, hopeful novel about one woman's return to war-ravaged Mogadishu" (Time)

Called "one of the most sophisticated voices in modern fiction" (The New York Review of Books), Nuruddin Farah is widely recognized as a literary genius. He proves it yet again with Knots, the story of a woman who returns to her roots and discovers much more than herself. Born in Somalia but raised in North America, Cambara flees a failed marriage by traveling to Mogadishu. And there, amid the devastation and brutality, she finds that her most unlikely ambitions begin to seem possible. Conjuring the unforgettable extremes of a fractured Muslim culture and the wayward Somali state through the eyes of a strong, compelling heroine, Knots is another Farah masterwork.

Release date: February 1, 2007

Publisher: Riverhead Books

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Knots

Nuruddin Farah

Feeling like a different person with a brand-new selfhood, so to speak, Cambara comes out of Zaak's house the following morning, dressed in a head-to-foot veil in the all-occluding shape of a body tent. To top it off, she has worn a strip of muslin cloth, which she holds between her teeth, like a horse with a bit, to keep it firmly in place, covering her entire face. She is donning the all-hiding garment for the first and only time in her life in the hope of disguising her identity. She walks with the consciously cautious tread of an astronaut taking his very first steps in outer space. Her forward motion plodding, her every gait a pained shuffle, her pace is as slow moving as that of a camel with its feet tied together. From a distance, she looks like a miniature Somali nomad's aqal on wheels.

Cambara is on her way to her family's expropriated property, discreetly consulting a map she has drawn from memory; Zaak, along with the driver, took her to within a block of the house late yesterday afternoon. She is finding it cumbersome to do so or to look around, hampered by the all-obstructing veil. Her feet feel trapped, her chest choked and her motion hindered. She is hot; she is boiling under the collar like a traveler hauling heavy bags she does not know what to do with. She is angry with herself for not returning to Zaak and then changing into an easy-to-wear garment and supplementing this with a niqab, a mere face veil.

She slogs with the slowness of a van with terrible shock absorbers, leaning this way and then that in complete disharmony; she is in a great deal of discomfort, perspiring heavily inside her bothersome veil and hitching up her cotton drawers as though expecting that she might sense some air passing through. Notwithstanding all this, she lumbers on, convinced that she will tower above potential aggressors in the likeness of armed youths if they attack her from close range, thanks to her hidden weapon of choice, a knife tucked away in her pocket. Cambara has always seen herself as a potential member of a cloak-and-dagger sorority, and she thinks that a knife is handy when one is surprising an armed foe who is expecting one to be unarmed.

She walks tall and well built; she is very imposing, very impressive; she fearlessly hobbles along. She draws her eyebrows close together in concentration, her mind busily sorting out the thoughts coming at her in waves. She is thinking about the number of codes that she has broken both before coming here and since then. Even though she is officially married to Wardi, she is living alone in a house with Zaak, who is not her spouse. She has done this before under a different, albeit deceptive context. Of course, this is not Saudi Arabia. There, to enter a house, you use one of two entrances; a small, almost secret side door for the women and a bigger, more prominent one for the men. It amuses her to remember the number of times many a Somali living in those parts has committed a faux pas. Some of them have received fifty lashes for presenting themselves at the wrong door and scandalizing the household, with the women looking through the peephole, giggling, and then reporting to the harridan who chaperones the female brood. Harum-scarum and in terrific haste, the hag might ring the principal male householder, who might in turn phone the police to deal with the menace.

Only now does she wonder if she needs to go to the property in a disguise of sorts, considering that Gudcur, the warlord, has no idea who she is and does not know her genuine self. No doubt he or his family may suspect the motives of her visit, which is why, in spite of camouflage, Cambara has to think of plausible grounds that will enable her to gain entry between now and when she is ready to risk asking to be admitted. By then, she will have crossed and recrossed numerous boundaries and will have come upon the moment with which she will mark the action that will define her success or failure. She hopes that she will survive the perilous course on which she is moving, unafraid.

She has had warnings about the dangers that await any man or woman visiting or living in Mogadiscio, a city rampant with the ghosts of its innocent dead.

Her eyes are red like worry beads. She turns her thoughts away from herself for a moment and focuses her attention on the houses on either side of the road where she is walking. Nothing pretty to hold her interest; the streets have the destroyed countenance of a bombed tunnel that has fallen in on itself, and the houses boast the damaged look of a tin, now empty, crushed and lying abandoned by the roadside. She strides forth, sensing that she is separate from her surroundings not only because she is veiled but also because she is wary of running into youths who have more vigor than eunuchs do and who may try to force themselves on her, being presumably alone and unprotected.

Gray as her self-doubts, her sangfroid refuses to acquiesce to her fear; she taps her inner strength for wise guidance. Despite her ambivalence about wearing veils, she wishes someone had taken a photograph of her in the body tent. She assumes that she looks a perfect marvel, a whirl of wonder wrapped in the mysteriousness of a voluminous veil, as surefooted in the sharpness of her bodily responses to the dangers that may be posed as she is relaxed in her knowledge that she can defend herself. She pauses in her stride to observe two women wearing less elaborate veils passing. Farther up the road, coming her way, there is yet a third in a class of her own—she thinks of a dervish spinning a holy trail of dust raised in the act of Sufi worship-in-dance.

She resumes moving, commensurately conscious of the yet undetectable dangers lurking in every corner, up the road, down the drive, and in the alleys. Why? Of course, she is frightened. However, she works hard not to show her fear, her strides shortening like a fat-bellied mosquito climbing out of a deep crevice in the darkness of dawn, mindful not to allow doubts to overwhelm her. Neither does she want her worries to ride the cusp of her self-recrimination. On top of her fears, she is enraged when she thinks about Wardi's treachery, which led to Dalmar's death.

The weight of the knife in the pocket of the loose-fitting caftan she has on underneath the body tent reminds her of where she is and why. Then she remembers buying the veil in its soiled state from an outfit in Dearborn, Michigan, where there is a large and well-established Yemeni community that came to this part of the United States in the thirties. The shop specializes in every imaginable outlandish wearable originating in an Islamic country. She drove over the border to Detroit and then to Dearborn. There is no better camouflage than a body tent, not merely because it looks so theatrical but because it allows a woman to walk with a strut and get away with it. Possibly, everyone will assume that the unevenness of the ground is affecting her gait adversely. She views the world from her vantage of knowing that so far, luck has taken a bit of a shine to her: Zaak meeting her at the airport and driving her home. That he has been wicked to her is all to the good too, as it has prompted her into quick action without relying on him. Then there is the boy soldier, SilkHair.

A rush of anxiety overpowers her as the other veil-wearer whom she saw earlier from a distance comes into view. Cambara is afraid that the other might work out that she is falsely hiding her identity; she knows that she does not belong to the same order as the women she passes by, women covered in a swathe of hand-me-downs, very unlike her own, which is of top drawer, devised in Afghanistan, as the Dearborn salesman explained, for the wife of a top Taliban dignitary to don on special ocaasions. Will it be obvious not only that she is from elsewhere but that she is not a local woman on an errand to a corner shop to buy a pound of sugar and a soda?

Here, at the junction, traffic is on the increase, the odd car rolling along, ramshackle metal rattling and issuing white smoke. Twice she senses the women's piercing stare, making her believe they see through her deceit, and she shudders in panic. She does not want to contemplate what will happen to her if someone discovers her disloyalty. She is so distraught at the thought of being found out that when three women stop and stare at her, one of them commenting that, judging from her gait, she is most likely “a foreigner” unaccustomed to wearing a veil, her knees weaken and she falters in her dodder. There is one advantage to putting on the veil though: No man focuses his predatory lust on a woman so dressed.

Cambara guesses that she is half a kilometer away from her destination, which has felt longer, because of her chameleonlike shuffle. The problem is that Zaak did not show her where the family house is in relation to his house. Vowing not to have anything to do with her madness, he distracted her from concentrating on mapping out a workable, time-saving way of getting here. He kept harping on the fact that one must buy Gudcur's goodwill with a handsome payment, up front, in cash. Cambara does not want to hear of buying back her own house. She says, “I won't pay these murderers a cent. No way. My parents worked hard to own these properties.”

For years, her father worked as a journalist until the tough going got tougher and it became difficult for him to practice his profession honorably. Then he set up a printing press, with Arda running the business part of it. The press specialized in printing visiting and wedding cards, and employed a staff of ten, excluding the cleaners, the menial workers, and several hangers-on who were the family's distant poor relations. He worked diligently, leaving very early in the morning to open up for business and coming home late, bone tired. However, even though he was good at making money, he had a huge failing: He was the proverbial spendthrift and knew not how to save or how to invest wisely. It fell to Arda to do what was necessary. Astute, she was adept at making people and money do what she wanted them to—propagate phenomenally as do plans and animals when the conditions are right. She managed the money side just as she managed the hearts of people, who gave their all to her and a lot more too. Before long, several embassies were signing lucrative contracts to print their invitation cards locally; some, like the Canadian Liaison Office, even requesting that she act as their local agent to deliver the cards by hand on its behalf.

Cambara's family owned two properties and, thanks to Arda's foresight and keen profit-making acumen, invested the surplus funds overseas, in Canada, when it was not fashionable among Mogadiscians to do so. The family—her parents, herself, and Zaak—lived in the modest one, a bungalow with six rooms, two bathrooms, and a small outbuilding with its own toilet facilities, in which the family accommodated long-term guests. However, the property that she intends to repossess is the larger one, bought by her father on her mother's advice and described, in estate-agent terms, as a worthy investment. An upmarket property, it had pride of place with direct access to its own beach, not to speak of an immense garden, built to accommodate a large function. She remembers how—when she was young in Mogadiscio, when Somalis were then at peace with their own ideas about themselves and proud of their uniqueness as a nation—her parents raised a huge monthly income from renting the upmarket property to the Canadians, who used it as a guesthouse for their Kenya-based embassy officials during their brief visits to Somalia.

Her father's printing business helped settle almost all the family expenses, including Cambara's private schooling and Zaak's boarding school fees. The rent money from the property paid for the occasional trips abroad, and, to her mother's everlasting credit and management skill, the family put away the savings, which paid for Cambara's college education in Canada until she got a scholarship and then later helped buy an apartment for her to live in in Toronto. Sadly, Cambara did not return home in time before the collapse. However, her parents got out, flying first to Nairobi and then joining her in Toronto for a while as her guests. Half a year later, they relocated to Ottawa and bought their own place, a good-sized apartment in a housing complex in the eastern suburbs of Ottawa, close to Arda's Canadian friends in the diplomatic corps, with whom she had frequently dealt when they visited Somalia and whom she invited often to dinner whenever they were in Mogadiscio on some diplomatic business.

Nothing gave the newly relocated couple as much pleasure as seeing their daughter in her debut as an actor on the stage. There were rave notices in almost all the major papers, one of them singling her out as the best new talent to be revealed in Canada in years. These reviews—and the fact that her parents enjoyed the show—helped stir Cambara's blood so much that she believed she had an excellent chance of becoming a full-time actor. To supplement her income, she trained as a makeup artist, investing in it as a business, while she waited for a breakthrough.

Now she slows down considerably, almost coming to a halt, as the family house rears into view. Her heart racing, her brain on the boil working overtime, she has hardly decided what to do next when, nearing the gate to the property, she discovers it ajar, a large stone keeping it from closing. She sees evidence of life in the gate remaining half open, but there is no way she can determine who has left it that way and why. It was common enough for people to leave their doors open night and day when she lived in Mogadiscio and you could take peace for granted. Later, with kickbacks and other forms of corruption creating overnight millionaires, the city became flooded with the unemployed, the poor, and the migrants from the starving hinterland, and fences went up faster than you could tally the changing death and birth statistics. Sometime later, residents upgraded the fences, putting broken glass, razor blades, and electric wire on top to deter robbers. Imagine: an open gate. What can it mean?

As she waits, anxiety throws Cambara into an agitated state, with the up-and-down convulsions of her chest resembling the suddenness of an asthmatic attack invading at short notice, and she breaks out in heavy perspiration. Then the actor in her takes over, and she calms herself down, wipes away the sweat from her forehead, and decides to act the part, improvising, inventing. After all, she knows what she wants, but the woman at the gate who is small and in advanced pregnancy has no idea who Cambara is. It will be her ill fortune if Gudcur is at home asleep, recovering from a long night of qaat-chewing orgy. She hopes that there are more rewards in what she is doing than there are risks.

She takes one long, last look at the half-open gate, the sight of which, fear and suspicion aside, makes sobering imagining. Cambara nods as though agreeing with the rightness of the decision, and plucks sufficient courage to move speedily toward the woman at the gate before questioning her own sanity.

Cambara leans against a wall, hidden from view, her heart pounding terribly, the circulation of her blood going anxiously faster than is good for her. The whole area, when she has had a moment to survey it, strikes her as being more ruinous than she has expected: a run-down rampart built to defend a soon-to-fall city. Tied up in knots churning inside her guts, she takes her time looking around for anything or anyone that might pique her interest.

She is thinking long and not without despondency when, by a singular stroke of good fortune, the woman heavy with child waddles wearily out, carrying out a bucket. The woman, in virtual rags, empties the filthy contents of the bucket into an open sewer twenty or so meters to the left of the gate. Whatever words Cambara has meant to use, words that she has rehearsed in her head endless times and with which she might explain her business of being here, catch at her throat, threatening to choke her and refusing to let go. Only after the actor in her reemerges and takes over, and she is able to breathe a little more freely, does she push aside the strip of muslin that has served as a face veil, the better to inhale or exhale normally. It is then that the woman becomes aware of Cambara's towering presence. Startled, the woman drops the bucket, cradling her head protectively with her hands and bracing herself for a blow, noisily breathing in and out, clearly in fright.

Cambara, her skin crawling with embarrassment, enunciates her speech. She says the one word “Water,” likening it to the magical properties of a mirage and investing in the word everything paradisial that everlasting life has in store for one. The woman rubs her eyes with the heel of her soiled hands, then wipes her cheeks dry with the edge of her robe, exposing her advanced pregnancy and a larger-than-usual belly button.

When she is certain that she has the woman's full attention, Cambara speaks tentatively in her attempt to assure the woman that she has lost her way to the shopping complex and desperately needs some water to drink. She feigns a dry throat, and shortness of breath, from her thirst, and says “Water” repeatedly until the woman nods a couple of times, indicating that she has heard.

Cambara adds, “My hosts have told me that there is a small shopping complex in this neighborhood where I can get some bottled water. But I must have missed the right turn, have I?”

The woman looks up, her eyes filling with a fresh sense of welcome relief. “You've missed the turn. It is a couple of streets down this way,” and she points, the ends of her fingernails charcoal-black with residual dirt, “then you turn left, and the small shopping block is there, you can't miss it,” replies the woman.

“There is a general store?”

“There is a general store for foodstuffs, and a few stalls where you can get fresh vegetable produce, but you can't get meat there,” the woman informs her. “But your hosts ought not to send you out on your own. It is not safe for a woman to be on her own in these parts of the city.”

The woman retrieves the bucket before beckoning her to follow her and waddling ahead of Cambara into the house. A smile adorns the woman's lips. She keeps the pedestrian gate open, half curtsying, and lets Cambara go past her. Cambara walks in warily and turns around a little awkwardly, waiting for the woman to close the gate behind them. Then she winces at the thought of harming this woman or her child on impulse, in self-defense or in her desire to recover her family's property at a future point. She hopes to be on this woman's good side, at least until she knows more about her relationship with the minor warlord. She resolves to shut out every moldering rot in the image she has constructed in her head in order to take the woman into her trust.

“Let me get you some water,” the woman says.

The woman gone, Cambara stands in the forecourt of the house, with the carport, empty of vehicles, to her left and the large gate now secured with a chain. She takes things in at a startling speed. She calculates the enormity of the ruin all around her and at a guess assumes that it will require a great deal of funds to repair the damage done to the property. She reckons that to make it rentable or habitable, nothing short of destroying everything and rebuilding it from scratch will do. She sees irredeemable wreck everywhere she looks: the walls scaling in large segments; the wood in the ceiling decomposing; the toilet facing her with its door gaping open emitting rank evidence of misuse; the windows emptied of glass panes; the carpets rolled up and stood against the outside wall, in a corner. Cambara retches at the sight of so much callousness; she places her hand in front of her mouth, as if needing to vomit into it.

Cambara looks to her right and finds the woman extending a glass to her, the color of the water mud-brown. She receives the proffered glass, noticing smudges on the outside of it—maybe the result of the woman's moist fingers—and murmurs a feeble thank-you. To earn the woman's trust, Cambara puts the glass to her lips, and takes a lip-wetting sip.

The woman asks, “Would you like to sit down?”

“Yes, I would,” says Cambara.

“Let me get you a decent chair, then.”

The woman moves into the house with renewed enthusiasm, then up a staircase, heaving forward ploddingly, like a dung beetle shifting its ration up a steep gradient. Cambara now entertains herself with an outrageously daring thought, on which she acts forthwith, no hesitation at all. Having seen the ruinous state of the outside of the house, she wants to find out what the rooms are like, inside. Who lives in them? What manner of furniture is there? But before taking her first step, she covers her face with the face veil, nervously biting the strip of muslin and sucking it in to the point of wetting it. Aware that nothing in her intuition or in her sense of general desperation can have prepared her for this derring-do, she enters the room facing her. Through the half-open door, she can see confirmation of the presence of children from the clothes that are strewn around the mattresses and the bunk bed. Cambara presumes that the children are not this woman's, so whose are they? How many families are sharing the house?

Yet she does not pause or draw back, as though answering to a stronger pull, for she has known the house inside and outside, played in it when it was under construction, and came to it when her mother, Arda, was showing it to the estate agent who would rent the property. Of course, she is well aware that embarking on such a dangerous mission is foolish, to say the least. All the same, she lunges forward at the same time as she reminds herself that she might not have abandoned herself to such a sudden impulse or behaved in this carefree way were it not for the fact that the property had been hers and she intended to repossess it. Could it be that her son's death, the fierce falling out with Wardi, and her beating him up have made her reckless, unafraid, indifferent to danger? What the hell, she thinks and pushes the door open, goes in, and then shuts it behind her.

With the curtains drawn, the room is very dim, until she removes her face veil. In addition, there is an oppressive odd mix of odors, principally of unwashed bodies. Her refusal to display fear helps her give the room an unhurried good scour until she sees the vague human forms, sleeping figures on the mats on the floor. Then she puzzles out the shapes of a couple of Kalashnikovs within reach of two of the men and a submachine gun close to one man, who is an island unto himself. The man, bare-chested and young, sits up in a startle, his sleep-squinted eyes finally focusing on Cambara. Befuddled, the man's dreamy look dwells on the tall, all-dark, motionless figure, and he is unclear in his head if he is conjuring her up or if she is there as real as he is staring at her. He is unable to decide what to make of her veiled presence; he shakes his head in disbelief, then listens to one of his mate's snoring rumpus and returns to his interrupted sleep. Cambara waits long enough for his breathing to even up, her hand always on the Swiss knife. Eventually she slips out of the room, closing the door gently.

Once out of the room, Cambara is face to face with the woman, whose unfriendly bearing and bothered expression almost prompt Cambara to violent action. The woman asks, “What were you doing in the room?”

“I needed a toilet,” Cambara says meekly.

“You should have waited for me,” the woman says.

Cambara says, “I had no idea.”

The woman's irritation lends her voice a harder edge. She says, “What do you really want?”

“A toilet, please,” Cambara repeats.

“First water, then a toilet. What next?”

“It's urgent,” Cambara says. “The toilet.”

“Follow me, then, and stay with me, you hear.”

The damp, rank odor hits her with a vengeance, and she cannot bring herself to close the toilet door, so penetrating the ferocity of its accumulated essences that Cambara almost brings out the vinegary intimations of her salad of a couple of days ago. She struggles to open the window, even if slightly, only it won't budge, no matter how hard she leans against it, pushing with all her might.

Cambara comes out of the toilet sick, like a cat unsure whether it is retching or coughing. From the look on the woman's face, Cambara concludes that she can guess what monstrosities she has seen: the accumulated brownielike concentrates floating in the toilet bowl to the top, almost welling out. On coming out, she takes in a fair dose of fresh air and then lights upon the woman's smile.

Her back to Cambara, the woman says, “They are worse than animals.”

Cambara does not bother to ask the woman to elaborate. She thinks she knows whom the woman means. The upshot of it is that the woman's statement helps to break the ice.

Besides, exhaustion is ultimately having its toll on the woman, as evidenced by the many unfinished tasks still waiting for her: adult clothes soaking and in need of washing; children's school uniforms that have been washed, which need to be neatly folded, the creases ironed out; lunch to be cooked; the floor to be swept. How can a woman in her advanced pregnancy hope to finish these all on her own? Cambara thinks how, since her arrival, her own life has been taking a basic design in which she steps in to put other people's lives in some order. If there is anything positive about this, it is that she has less time to brood on her loss, to mourn, or to grieve and eat her heart out.

Cambara considers completely removing her face veil. After some hesitation, she takes off the body tent altogether, and with the exposure to the air, she feels lighter in her blood and bones. As she methodically folds the body tent into some shape easy to get into later, she gives the clothes she is now standing in a moment's scrutiny, no doubt wondering if it is wise to do away with her disguise, her guile. She shrugs her shoulders, what the hell, rolls up the sleeves of her caftan— only then becoming conscious of the weight of the knife in her pocket—and offers the woman a break. The woman is so worn out she is in no position to refuse. Scarcely has Cambara done a stroke of domestic work than she takes the measure of the woman's exhaustion.

She says, giving herself a false name, “My name is Xulbo. What's yours?”

The woman is silent for quite a while. She struggles to sit, now rubbing her back, now her hips, staring ahead of herself, her eyes rolling in amazement at what is happening here: a help at hand, what kindness! The woman is rigid in her appearance, preoccupied, busy worrying a blackhead, picking at it. Maybe she is deciding whether to accept Cambara's offer to help with the house chores; maybe the idea of telling her name to a total stranger does not sit easily with her or with the men sleeping off a night's qaat-chewing.

Finally she says, “My name is Jiijo.”

Cambara knows that this is the short form of Khadija, a name common among the woman's Xamari community, the cosmopolitan residents of Mogadiscio, believed to have descended from Persians, Arabs, and Somali.

Cambara, the adored daughter of her parents, who never lifted a finger in this house in all the years that the family had owned it, now gets down to the serious business of washing the dishes and the clothes, and mopping the floor. It surprises her how much pleasure she is deriving from performing manual labor and how a few minutes' work has so far opened doors that might otherwise have remained closed to her. When she thinks she has done enough, she asks, “How many months?”

“Eight and a half.” “Your first baby?” The woman nods feebly. Cambara works her fingers to the bone, intent on completing as much of the job as possible before the return of the young children. She has seen evidence of clothes, boys' broken plastic toys, girls' dolls— when she surreptitiously entered the room with mattresses on the floor.

Cambara does the best she can under the rushed circumstances. She does not take leave of the woman or of the house before she gets a couch for Jiijo to lie on. In fact, she tiptoes out only after Jiijo has started to embark on an exhausted woman's snore.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...