- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A SOLDIER WITHOUT A PAST A wounded knight awakens alone on a hillside. His only memory is that of a mighty battle - but there has not been a battle in this place for more than a hundred years. Tired, hungry and alone, the knight must rely on the help of others if he is to survive. Kindness takes him to the magnificent city of Zamerkand, but what lies inside the city gates will leave his life in more danger than ever. Safety can only be found in the ranks of the mercenary army known as the Red Pavilions. But joining up is only the beginning of an extraordinary quest for the man who calls himself Soldier - a quest for revenge, for truth and for his own identity.

Release date: September 12, 2013

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

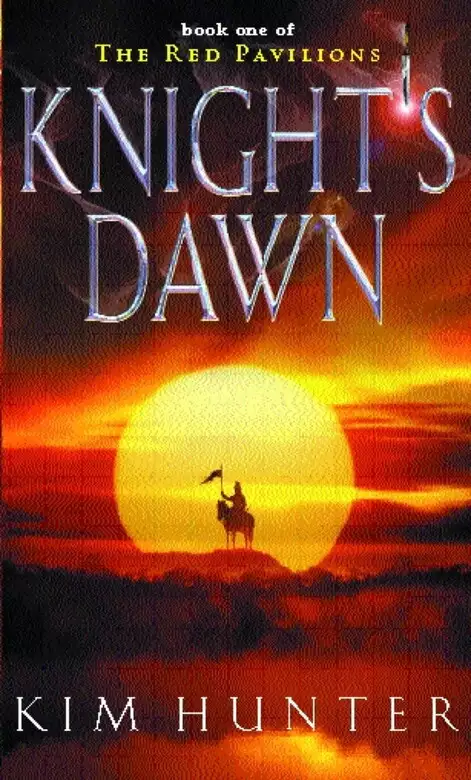

Knight's Dawn

Kim Hunter

The knight wearily opened his eyelids. There was a dead snake near his foot, with a bloody cudgel next to it. A raven hopped around the snake and stick, yelling at him.

The light hurt his eyes. A pale white sun glared down on the knight from the heavens. He was on a hillside, a slope, on which there had been a great battle. All his muscles ached from the fighting. He felt utterly fatigued. It was all very hazy to him now, blurred and warped. He tried to recall what he had been doing in this battle and who the armies were.

If he allowed his mind to look back he could see the battle in full bloody murder. Around him he beheld a great heaving mess of men, armies rolling one over the other, multitudes of men tumbling like waves of water into hordes of other men. They hacked with battleaxes, thrust with swords and spears, beat each other with maces. Weapon points entered flesh through seams and chinks in armour. Arrows thudded into the chests of knights, penetrating breastplates as if they were paper. Heads and torsos were split asunder. Skulls were battered and crushed by warhammers. There was fire and blood and the bright flashes of a hundred thousand blades, lance heads, pike tips.

‘There he is! Do you see him? Down by the tree line.’

The vision of the past washed away and the knight’s eyes were clear once again. He stared at the area indicated by the raven. There was a horseman down there, wrapped from head to foot, swathed in calico dyed with indigo, only his eyes exposed. The man was a obviously a lone hunter. He rode his piebald steed with his knees only, leaving his hands free. On his left wrist was a hawk wearing trailing scarlet jesses. There were golden bells on its ankles. In the hunter’s right hand was a small black crossbow, with a bolt in the breech.

‘I see him,’ said the knight, not considering why he was talking to a bird. There was too much other strangeness in the air to worry about things perhaps unthreatening. ‘I shall keep him in view.’

In his mind’s ear he now heard the shrieks of wounded and dying men on the hillside around him. Some cried for a physician, some for their mothers, some for their comrades. The cries were pitiful to hear. There was the yell of a decapitated head, as it continued its shout of terror even after leaving the shoulders of its owner. There was the clashing of steel on steel, thousandfold, ringing through the surrounding hills. Screams, groans, death rattles. It was a cacophony which filled the knight’s head. The bullroarers and the trumpets. The animal-skin drums and the log-drums. The whistles and bladderpipes and ox-horns. To the ears of the animals in the woodlands and valleys, this deafening discord must have sounded like the end of the world. Especially when their own kind were being slaughtered: the noise of screaming horses as they are disembowelled by the lances of knights, or limb-lopped by foot-soldiers, is something no creature ever forgets.

‘See,’ said the raven, ‘the hunter views his quarry.’

A purple heron flew overhead and the hunter released his hawk. The raptor shot skyward, after the heron which had now swerved in flight. There were few signs of panic in the fleeing prey. Only the leisurely flapping of the great wings and the harpoon head stretched a little further forward.

At that moment, while all eyes were on the hawk and the heron, a black boar broke cover. It rushed at the hunter’s steed from the flank. The horse’s eyes rolled and it whinnied in fright, rearing to the right. The hunter steadied his mount with his knees and took careful aim with the crossbow. There was a thwunk and the bolt struck the boar in the brain. The beast’s legs folded under it and it rolled, crashing into a thicket, dead as a rock. The hunter then looked up to see the heron plummeting from the sky, the hawk having stooped and struck.

‘We should go and speak with this man,’ said the raven. For the first time the knight turned his attention to the talking bird.

‘Who are you? What are you? Did you come to feed upon the dead?’

‘Dead? What dead?’ asked the bird.

The knight looked about him quickly and then remembered. It had all taken place in his mind. Yet he knew there had been a battle. Looking down at himself he saw that he was wounded in a number of places. They were not serious cuts or abrasions, but they were fresh. His uniform was filthy and in tatters and he wore the remnants of bloodstained armour. He was caked in sweat and dust. His throat was parched: choked with the same dust that decorated his clothes. From his belt hung an empty black-and-silver scabbard, twisted and bent. Stitched on the leather of the scabbard in silver-wire thread were the words, Kutrama and Sintra. The knight was suddenly bewildered. Who was he? What was his name? Why was he lying on this hot hillside, talking to a raven who was looking at him as if he were a corpse?

‘Why do you stare at me like that?’

The bird said, ‘A crow can look at a king.’

‘Well, I don’t like it. If you want to end up on a gibbet, just keep on doing it.’

‘Irritable beggar, aren’t we? No need to get annoyed. I was just looking at your eyes. They’re blue. I’ve never seen eyes that colour before. Everyone around here has brown eyes.’

The knight, who had been unaware of the colour of his eyes, touched his eyelids.

They turned away from each other to stare at the hunter, who was now gathering up the carcass of the boar and strapping it to the rump of his mount. His hawk was enjoying the brains of the heron, where the hunter had cracked its skull with a rock. This was the raptor’s reward for a clean kill. The hunter then sat on a rock and began plucking the heron, purple feathers flying over his shoulders. As the knight descended, the raven hopping on behind, the hunter had finished cleaning and gutting the heron and was preparing a wood fire on which to roast it.

There was a beck nearby. The knight went straight to this and began scooping up the water to drink: clear water, but not sparkling. It was midday, the sun horizontally overhead, but the warmth from it was weak.

The knight was then aware that the hunter was speaking to him.

‘Are you in need of assistance?’

The hunter’s voice was confident, firm, but not very deep. He looked and sounded like a slimly-built youth and his delicate movements offended the knight’s masculinity. Dark-brown eyes stared at him from a band of flesh beneath the swathes of blue calico. There was enquiry there, if not concern.

‘Where am I?’ asked the knight. ‘Has there been a battle here?’

The hunter said, ‘Your eyes – they’re blue.’

‘Does that matter?’

The hunter shrugged and delivered answers which were crisp and to the point. ‘You are just south of the Ancient Forest, near the petrified pools of Yan. To my knowledge there has been no battle hereabouts for over a century.’

‘But, that can’t be true. Look at me!’ He opened his arms and invited inspection. ‘I am wounded. My uniform is in shreds.’

‘I cannot account for your condition. There has been no battle here. What is your name? From what country are you? This is not a time to be wandering Guthrum alone. There are brigands and bandits abroad, and the queen’s soldiers are suspicious of lone travellers. They have licence to execute strangers found roaming the countryside. If you do not end up with a broken skull, you might be hanged from gallows such as those you see on that hill.’

The knight looked up. In the distance, beyond the stream, was a triple-gallows, with several corpses hanging from it. As the soldier stared at this place of execution, seemingly miles from any village, town or city, he noticed that few of the hanged figures had hands on the ends of their arms.

‘Guthrum,’ murmured the knight, grasping at the word and inspecting it closely. ‘That name should probably mean something to me, but it doesn’t. And as for my own name, I can’t remember it. Do I even have a name? I feel I am in some kind of dream, or nightmare. I know nothing about myself.’

‘Perhaps you are mad?’ suggested the hunter, matter-of-factly.

‘No, no. I do not feel mad.’

‘Madmen never do. To whom were you speaking, as you were coming down the hill? To yourself?’

‘Why, no,’ the knight turned and pointed to the raven, hopping on some stones in the stream. ‘To that bird. It speaks as well as you or me. Raven, say something to the hunter.’

The raven simply sipped at the running water with its beak. It looked like any of the other birds in the area. There was no comprehension in its demeanour or its eyes.

The hunter nodded slowly. ‘I think you are mad.’ He pointed to the roasted heron carcass, part of which he had already eaten. ‘You may have some of that if you’re hungry. Then I must be on my way.’

‘Wait!’ said the knight, quickly. ‘Where are you going?’

‘Why, back to Zamerkand of course. I would rather return home before nightfall. If this countryside is dangerous during the day, it is ten times worse at night. There are bears and wolves to contend with, not to mention—’

‘Take me with you,’ pleaded the knight. ‘I have no weapon with which to defend myself and I don’t know the way. I can assist you if you are attacked. Forgive me, but you do not look strong enough to defend yourself against enemies on the road.’

The eyes hardened. ‘Did you see me kill the boar?’

‘Hunting is a different matter. It takes more than a sharp eye to kill a human. You need the strength of will.’

‘Strength of will? A moment ago it was my physique that was important – now it’s whether I have the stomach for killing. You really should make up your mind what it is about me that you find lacking.’ The hunter stared hard for a few moments, then nodded. ‘You may follow my horse. I can’t take you up behind me because, as you see, I am carrying a wild boar.’

The knight felt inclined to argue that his life was more precious than a boar’s carcass, but the hunter had already swung himself back into his saddle. The hawk had taken to the air again, but the hunter whirled a silver lure around his head, on a long piece of cord, and the hawk came down to his wrist. Then the hunter set off at a leisurely pace, his palfrey high-stepping through the woods, the ground being spongy with thick moss. The knight, weary though he was, trotted on behind chewing on a drumstick. At one point the raven flew down from a branch and landed on his shoulder, to whisper in his ear, ‘You’re mad, you are. Fancy talking to a black bird.’

The bird then flew away, leaving the knight bemused and angry, wondering whether indeed the raven was right.

During the journey the hunter stopped once to treat the knight’s wounds with herbs and healing plants. The cuts were fairly superficial, but there was still a danger of infection. Deep inside him was a bitterness, a hatred for something he could not explain to himself. These feelings were like dark shadows in his soul, but he did not know what was casting them.

In the forest, great spiders’ webs joined high oak branches with the ground. The soldier inadvertently ran through these, getting his face and hands gummed with the sticky threads. When they left the woods and began crossing boggy ground, there were clusters and knots of snakes in every peat hag: far too many to be natural. Every so often they came across another gallows, with hanged people dangling from the bar. In most cases the hands were missing, though some fresh corpses were intact. The knight wanted to ask the hunter about this, but could not catch his breath enough to be able to hold a conversation.

After three hours of travelling, when the clouds were pink islands in the evening sky, the two men crested a ridge. The knight found himself looking down on an immense walled city with turrets and towers rising as thick as spears from an army of closely-packed warriors. Zamerkand.

There were flags and banners fluttering from every pinnacle. Dark, triangular windows peppered these spires and the wind blew through them and played melodies as if they were holes in a flute. Domes and cupolas crowned every other one of the tall columns, upon which the weak evening sunlight glittered with malevolent sheen.

The knight’s aerial view revealed that within this massive fortification of tall spiky buildings were several palaces, parks, gardens and courtyards. Fountains showered expansive lawns, around which were myrtle hedges, shrubberies and spinneys of conifers and deciduous trees. There were bright lakes and moats that flashed in the evening light. Moreover, a whole town existed within the city walls, with houses, cobbled streets, stalls and cattle pens.

Around the city were at least a hundred large tents – sandstone-red in colour.

An arched stone tunnel ran from one side of the city, across the open wooded countryside, its terminus out of sight beyond the hilly downs and woodland sweeps. The hunter explained that beneath this fortified tunnel lay a canal, straight as a silver arrow, which connected the city with the sea. Along this canal went trading barges, protected from attack by six-foot-thick walls, to meet with ships coming and going from a natural harbour on the Cerulean Sea. Trade with countries like Uan Muhuggiag, across the blue water, was brisk and profitable. It kept the citizens of Zamerkand reasonably wealthy, even during times of siege, when the countryside was ravaged by fighting.

‘What a wonderful place,’ said the knight, pausing to drink in this magnificent scene. He looked around him, at the silhouettes of several gallows on the neighbouring ridges, and down before the city gates at what appeared at a distance to be severed heads stuck on sharpened stakes. ‘Unlike the countryside in which it resides.’

‘Ah, as to that,’ said the hunter, having alighted, ‘you must understand that HoulluoH is dying. His grip on the world has slipped, and people are fearful. But all will be well soon. Things will right themselves once the new King Magus is in command.’

‘King Magus?’ queried the knight.

The hunter placed a slim hand on the knight’s shoulder, which made the tall, dark stranger to this land feel uneasy.

‘You really are a newcomer, aren’t you? Guthrum, my friend, is a region of many wizards, the greatest of which is the King Magus. It is he who ensures that those who have the power of magic do not abuse it. He maintains a balance in the land, between good and evil, nature and supernature, magicians and ordinary folk.’

‘Do the wizards have blue eyes?’ asked the knight, hopefully, wondering if he had special powers.

‘My dear friend, no one in Guthrum has blue eyes.’

The knight shrugged off the over-friendly hand from his shoulder.

‘I am not your dear friend and would prefer it,’ he said, ‘if you did not touch me in that manner.’

There was a twinkling in the eyes of the other, who appeared to be smiling beneath the mask of blue calico. The knight knew he was being mocked, but could not do anything since he was in debt to this person.

‘As you wish, soldier, but you may be in need of a friend in these troubled times, here in Guthrum.’

Soldier? That was as good a name as any. He had no other. Until his memory returned and he knew his identity he would call himself Soldier. It was a manly name, if nothing else.

‘I can take care of myself,’ he said. ‘Don’t you worry about me.’

Soldier stared down at the castle again. In the ruddy light of the dying sun, blood-scarlet in contrast to the whiteness of its midday face, he could see the red pavilions surrounding the city. He estimated that each pavilion would probably accommodate eighty to a hundred men and there were around a hundred pavilions. Ten thousand men. Each one of the pavilions had a pennon flying from the tip of the centre pole. These pennons bore a symbol but the distance was too great to identify them. When he asked the hunter he was told they were animal symbols – boars, eagles, falcons, cats, dogs – which denoted a company of men. Each pavilion was an entity unto itself and loyal in the first place to its commander. In battle it was the honour of the pavilion which was foremost in the minds of the soldiers. Men lived, fought and died for the pavilion and nothing was permitted to smirch its honour.

‘Who are in the pavilions?’ he asked. ‘Do they guard some visiting royal or noble?’

‘Mercenary soldiers,’ replied the hunter. ‘Troops from the land of Carthaga. Queen Vanda uses them to supplement her own army, when she is forced to wage war. Actually the Carthagans do the brunt of the fighting, while the Guthrumites usually end up supporting them. They have special qualities. They are brilliant warriors – brave, selfless, disciplined, dedicated to their duty – they’ve been in the pay of Guthrum for centuries now and are intensely loyal to us. Each soldier serves twenty years then returns to Carthaga. He can keep his whole extended family on his pay while he is a serving soldier and he receives a huge bonus for completing his time.’

‘Why are they outside the city walls?’

The hunter shrugged. ‘It’s the way it has always been. They never enter the city. Perhaps at one time they were not wholly trustworthy? It has become tradition now. The Guthrumite imperial guards are responsible for policing inside the city and for protecting the royal family. Carthagans protect the city from attack by outside hostile forces. If a larger army is required, then the citizens are armed and put in the field.’

Soldier and the hunter then descended from the ridge, with the raven somewhere around in the gathering gloom. As they approached the city Soldier could see that the Carthagans were a squat, broad-shouldered people. They were swarthy, with flat faces and square frames. He and the hunter were not stopped or accosted while they passed through the red pavilions. Soldier assumed this was because they were only two and hardly a threat to an army of ten thousand tough, battle-hardened warriors.

Soldier decided it would be a different story when they reached the gates of the city, decorated with an avenue of heads on stakes.

They walked through this ghastly gauntlet. Matted hair hung over eye-sockets picked clean by the birds. Tongues, also attacked by birds and insects, hung from between swollen lips. Noses and cheeks were pitted by the weather and other agents of destruction.

‘Help me,’ whispered one particularly gruesome skull as Soldier passed it by. ‘Help me, please!’

Soldier turned and stared at the head, startled by the voice, only to see the stalking raven squatting inside, staring out through one of the empty eyesockets.

‘Fooled you,’ murmured the raven, in a satisfied tone. ‘Fancy a bit of dinner? Plenty here.’

With that the black bird left the back of the skull and began pecking at the rotting flesh.

‘You’re disgusting,’ said Soldier, curling his bottom lip.

The hunter said, ‘Were you speaking to me?’

‘No, no,’ replied Soldier, wearily, ‘just to the raven. You know? My madness? I am a lunatic after all.’

‘Just so,’ said the hunter. ‘Come, we must enter the city before the gates are locked for the night. Otherwise we might have to share the hospitality of one of these pavilions. Good fighting men the Carthagans might be, but they are also among the legions of the sweaty and unwashed. Their favourite fare is wild-oat porridge dried in the sun, cut into slabs and fried in goat’s lard. If you want to sleep with the stink of axle grease in your nostrils and breakfast on oats fried in animal fat, that’s fine, but I rather look forward to a supper of fish and almonds, followed by a night in clean sheets bearing the fragrance of sandalwood.’

‘You would,’ muttered Soldier, under his breath, ‘but I doubt I’ll see better fare than fried porridge.’

There was a good deal of traffic going through and milling around the outer gate at this time of the evening. It was the hour of the day when those whose work took them beyond the city’s walls came back inside for protection during the night hours. There were coaches and horsemen, peasants with ox-carts, dog-carts and hand-carts, and lone men and women on foot, some carrying the implements of their trade: scythes, axes, saws, hammers. Many of the vehicles were piled high with faggots and wood. Others with animal fodder or vegetables. The way through the gate was ankle-deep in dung and though Soldier attempted to tread carefully, his leggings were soiled almost to the knee shortly after joining the queue. The whole area stank and the flies were large and bothersome.

Soldier assumed that they would be stopped by the outer guards on the gate and questioned, but they hardly even glanced at the hunter and himself. Once inside the outer ward however, it was an entirely different matter. They were almost pounced upon by four burly men in uniform and led to a gatehouse tower. The hunter was taken inside, while Soldier was made to wait. It was growing dark now and the lamplighters were abroad. There were brands in iron cages on the walls round about and these were being torched. Soldier felt it must be a wealthy place to have street lighting and was duly impressed by all the activity.

The hunter’s mount stood tethered to a post nearby, looking mournfully at the door through which her master had vanished. On its back was the boar the hunter had shot with his crossbow earlier in the day. Soldier was now extremely hungry and the thought of the boar roasting on a spit played havoc with his imagination. He wondered if the hunter would invite him to a meal, now that they were inside the city.

‘All right,’ said a guard, coming out and beckoning to Soldier, ‘in you go.’

Soldier stepped inside the tower to find himself immediately in a room where a scrivener in a grey robe sat at a desk. The man was elderly, with a wall eye and a rather sour look on his face. He was also quite ugly, being bloated and puffy-looking, with a poor complexion and some kind of rash on his neck.

‘Name?’ said the man in a bored voice, his quill pen poised above a great leather-bound book.

Soldier looked about him, bewildered. There did not seem to be another door in the room, yet the hunter was nowhere to be seen.

‘Where did the hunter go?’ he asked.

The scrivener looked up with his one good eye, impatiently.

‘Stranger,’ he said, in a quiet patronising tone, ‘I would like to get this over with as quickly as possible, so that I can get back to my soup, which is cooling on the table by the window. Soup is not my favourite fare, but it is one of the only meals I can digest in comfort these days, since all my teeth are gone and my gums are somewhat diseased. If you do not reply within three seconds, I shall have you thrown outside the city walls where you will spend the night – or not – depending on how soon the wolves get to you, most of whom, I am jealous to be so informed, still retain a full set of fangs.’

‘Soldier,’ said Soldier, quickly.

‘What?’

‘My name – my name is Soldier.’

The scrivener scratched away in his book, his left eyebrow raised and his tongue-tip sticking out of the corner of his mouth.

‘Soldier,’ he repeated. ‘Nothing more? Not “Soldier from Kandun” or “Soldier of Tyern”? Usually when one’s name is one’s trade, a town or a city follows. “Smith of Blandaine,” for example …’

‘Just Soldier.’

‘Then my next question is, where are you from, Soldier?’

‘From – from the Ancient Forest.’

The scrivener looked up from beneath his brows, his wall eye disconcerting Soldier. ‘The Ancient Forest? That region is uninhabited. What is more, you do not look like a local, like one of us, so to speak. You seem to be a foreigner and a very strange one at that. Blue eyes? I never heard of such a thing, not even amongst the beast-people beyond the water margin. You’ll have to do better than that, Soldier.’

‘Look,’ he blurted, ‘the truth is I don’t know who I am or where I’m from. I woke today on a hillside just beyond the Ancient Forest. I feel as if I’ve been in a great battle – I’m sure I have. But the hunter who brought me here said there had been no battle in that region for years. I don’t understand what’s happened to me, but I mean no harm to anyone in Guthrum. I simply need a safe place to sleep until my memory returns and I can put my life in order.’

‘Ah, yes, the hunter. You have money?’

‘Money?’ the soldier felt in his tattered pockets, around his belt for a purse, and came up empty. ‘No, no money.’

The scrivener put down his pen and smiled. It was a horrible expression, even worse than his scowl.

‘Then how do you expect to live?’

‘I thought – that is, I hadn’t really thought. But I’m willing to work. I’ll eat scraps for the time being. I’ll fight with the dogs for bones under the table. It doesn’t matter. What I need is time – time to recover my wits.’

The scrivener suddenly and surprisingly shrugged. ‘As you will. I understand you clutched the hem of the hunter’s garment and craved hospitality? In which case we can’t refuse you shelter, that person being a citizen of this state. You may have to sleep in the street, but that’s up to you and your fortunes.’ The scrivener pointed the goose-feather quill at Soldier as if it were a weapon. ‘But stay out of trouble. You’re lucky you were not caught and hung in the countryside. Am I understood?’

‘Perfectly. I will be the model citizen.’

‘You will not be a citizen at all, since you are an outlander. But you will be good or you will be dead.’

‘Yes, yes, you have my word.’

With that the scrivener called the guard. Alarmingly, Soldier was marched away towards a half-lit shack standing not far from the tower. He had thought he would be released immediately, but it seemed there were other procedures to go through. The shack turned out to be a blacksmith’s forge, with a great furnace making the place unbearably hot. There a tall, skinny man, whose skin was pitted with black scars from flying red hot iron filings, fitted an iron collar around Soldier’s throat and sealed it with a rivet.

Soldier yelled, as the pain of the hot rivet bit into his neck.

The smith grunted.

Still wincing, Soldier asked, ‘Are you from Blandaine?’

The smith stared. ‘Yes, how do you know?’

‘Because I have heard that people from that town are unfeeling bastards.’

The smith’s eyes hardened. ‘You be careful, stranger. When the time comes, it’ll be me who takes that collar from your neck. My mother was a gentle woman, but I have inherited all my character from my father, who was one of the queen’s torturers. The best at his trade, so I’m told.’

The guard laughed, and said, ‘Come on, stranger. On your way now. If I were you I’d make my way down to the canal district, where you’ll find the rest of the riff-raff.’

‘How long do I have to wear this thing?’

‘A month at the most.’

Once the iron collar was in place Soldier was allowed to go. He realised he had been given the collar so that he could easily be identified. People would know he was a stranger and be wary of him. He would be under observation, by the local residents, during all hours. If he turned out to be a thief, or worse, he would be banished from the city. These precautions seemed very reasonable to Soldier, even if he did feel a little bitter at being subjected to them. In dark times people protected themselves against infiltrators from the wildernesses.

His new iron torc was uncomfortable at first. It chafed his neck. But he knew he would soon get used to it.

Soldier made his way through the dimly-lit cobbled streets, not really knowing where he was going. Eventually he came across a canal, which he followed to a network of moored barges. The canals were fed from the water in the moat, which in turn received an inflow of water from the natural system of rivers and lakes beyond the city walls. He was now in the centre of the city. He went towards a quay. There he saw a sight that shocked him to the core.

The bloated body of a woman was floating in the water, caught up in the mooring rope of a small barge. Just as Soldier spotted her, someone came up from below decks and saw her too.

‘Bloody corpses!’ Soldier heard the bargee’s words quite clearly. ‘They stink in this weather …’

The bargee took a boat-hook and prised the cadaver away from his mooring line with as much passion as if it were the carcass of some animal. The white limbs and naked torso of the victim of some horrible violence – her head was split down through her nose and upper jaw – then went floating off on the current of the canal. The bargee grunted in satisfaction, before going below again. There had been no compassion in the bargee, only irritation that a lump of flesh had snagged on his boat. Soldier was appalled by the lack of sympathy shown by the bargee and the horrible nature of the woman’s wounds.

‘What is this place I have come to?’ he asked himself.

Sitting on the edge of a quay and contemplating his shadow on the water below, Soldier thought about his life. It amounted to only twelve hours. He had been born at noon, so far as his memory told him, and it was now around midnight. He knew nothing about himself. In his mind he clung onto those aspects of his short life which meant something to him. The hunter, for example. That they should have met on the edge of the fore

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...