- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

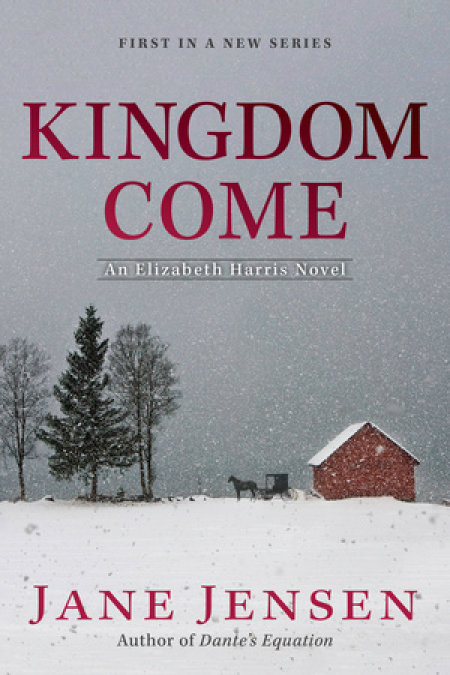

Synopsis

Amish country in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, has always been a place of quiet beauty—until a shocking murder shatters the peace, and leaves a troubled detective picking up the pieces…

After her husband is murdered, Detective Elizabeth Harris turns in her NYPD badge and moves back home, hoping that a quiet life in remote Pennsylvania Dutch country will help her overcome the dark memories of her ten years in New York. But when a beautiful, scantily clad “English” girl is found dead in the barn of a prominent Amish family, Elizabeth knows that she’s uncovered an evil that could shake the community to its core.

Elizabeth’s boss is convinced this was the work of an “English,” as outsiders are called in Lancaster County. But Elizabeth isn’t so sure. All she’s missing is an actual lead—until another body is found: this time, a missing Amish girl. Now Elizabeth must track down a killer with deep ties to a community that always protects its own—no matter how deadly the cost…

Release date: January 5, 2016

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Kingdom Come

Jane Jensen

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgments

CHAPTER 1: The Dead Girl

CHAPTER 2: Fistful of Seeds

CHAPTER 3: Bread and Milk

CHAPTER 4: The Naming

CHAPTER 5: A Lesson in Husbandry

CHAPTER 6: What She Hid

CHAPTER 7: The Girl in the River

CHAPTER 8: Pot of Gold

CHAPTER 9: Broken Fences

CHAPTER 10: Pulling Up Roots

CHAPTER 11: Germination

CHAPTER 12: In Custody

CHAPTER 13: Wheat from Chaff

CHAPTER 14: The Bloody Bower

CHAPTER 15: Drowning

CHAPTER 16: Snake in the Grass

EPILOGUE

Special Excerpt from In the Land of Milk and Honey

CHAPTER 1

The Dead Girl

“It’s . . . sensitive,” Grady had said on the phone, his voice tight.

Now I understood why. My car crawled down a rural road thick with new snow. It was still dark and way too damn early on a Wednesday morning. The address he’d given me was on Grimlace Lane. Turned out the place was an Amish farm in the middle of a whole lot of other Amish farms in the borough of Paradise, Pennsylvania.

Sensitive like a broken tooth. Murders didn’t happen here, not here. The last dregs of sleep and yet another nightmare in which I’d been holding my husband’s cold, dead hand in the rain evaporated under a surge of adrenaline. Oh yes, I was wide-awake now.

I spotted cars—Grady’s and two black-and-whites—in the driveway of a farm and pulled in. The CSI team and the coroner had not yet arrived. I didn’t live far from the murder site and I was glad for the head start and the quiet.

Even before I parked, my mind started generating theories and scenarios. Dead girl, Grady had said. If it’d been natural causes or an accident, like falling down the stairs, he wouldn’t have called me in. It had to be murder or at least a suspicious death. A father disciplining his daughter a little too hard? Doddering Grandma dipping into the rat poison rather than the flour?

I got out and stood quietly in the frigid air to get a sense of place. The interior of the barn glowed in the dark of a winter morning. I took in the classic white shape of a two-story bank barn, the snowy fields behind, and the glow of lanterns coming from the huge, barely open barn door. . . . It looked like one of those quaint paintings you see hanging in the local tourist shops, something with a title like Winter Dawn. I’d only moved back to Pennsylvania eight months ago after spending ten years in Manhattan. I still felt a pang at the quiet beauty of it.

Until I opened the door and stepped inside.

It wasn’t what I expected. It was like some bizarre and horrific game of mixed-up pictures. The warmth of the rough barn wood was lit by a half dozen oil lanterns. Add in the scattered straw, two Jersey cows, and twice as many horses, all watching the proceedings with bland interest from various stalls, and it felt like a cozy step back in time. That vibe did not compute with the dead girl on the floor. She was most definitely not Amish, which was the first surprise. She was young and beautiful, like something out of a ’50s pulp magazine. She had long, honey-blonde hair and a face that still had the blush of life thanks to the heavy makeup she wore. She had on a candy-pink sweater that molded over taut breasts and a short gray wool skirt that was pushed up to her hips. She still wore pink underwear, though it looked roughly twisted. Her nails were the same shade as her sweater. Her bare feet, thighs, and hands were blue-white with death, and her neck too, at the line below her jaw where the makeup stopped.

The whole scene felt unreal, like some pretentious performance art, the kind in those Soho galleries Terry had dragged me to. But then, death always looked unreal.

“Coat? Shoes?” I asked, already taking inventory. Maybe knee-high boots, I thought, reconstructing it in my mind. And thick tights to go with that wool skirt. I’d been a teenage girl living in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. I knew what it meant to care more about looks than the weather. But even at the height of my girlish vanity, I wouldn’t have gone bare-legged in January.

“They’re not here. We looked.” Grady’s voice was tense. I finally spared him a glance. His face was drawn in a way I’d never seen before, like he was digesting a meal of ground glass.

In that instant, I saw the media attention this could get, the politics of it. I remembered that Amish school shooting a few years back. I hadn’t lived here then, but I’d seen the press. Who hadn’t?

“You sure you want me on this?” I asked him quietly.

“You’re the most experienced homicide detective I’ve got,” Grady said. “I need you, Harris. And I need this wrapped up quickly.”

“Yeah.” I wasn’t agreeing that it could be. My gut said this wasn’t going to be an open-and-shut case, but I agreed it would be nice. “Who found her? Do we know who she is?”

“Jacob Miller, eleven years old. He’s the son of the Amish farmer who lives here. Poor kid. Came out to milk the cows this morning and found her just like that. The family says they’ve got no idea who she is or how she got here.”

“How many people live on the property?”

“Amos Miller, his wife, and their six children. The oldest, a boy, is fifteen. The youngest is three.”

More vehicles pulled up outside. The forensics team, no doubt. I was gratified that Grady had called me in first. It was good to see the scene before it turned into a lab.

“Can you hold them outside for five minutes?” I asked Grady.

He nodded and went out.

I pulled on some latex gloves, then looked at the body, bending down to get as close to it as I could without touching it. The left side of her head, toward the back, was matted with blood and had the look of a compromised skull. The death blow? I tried to imagine what had happened. The killer—he or she—had probably come up behind the victim, struck her with something heavy. The autopsy would tell us more. I didn’t think it had happened here. There were no signs of a disturbance or the blood you’d expect from a head wound. I carefully pulled up her leg a bit and looked at the underside of her thigh. Very minor lividity. She hadn’t been in this position long. And I noticed something else—her clothes were wet. I rubbed a bit of her wool skirt and sweater between my fingers to be sure—and came away with dampness on the latex. She wasn’t soaked now, and her skin was dry, so she’d been here long enough to dry out, but she’d been very wet at some point. I could see now that her hair wasn’t just styled in a casual damp-dry curl, it had been recently wet, probably postmortem along with her clothes.

I straightened, frowning. It was odd. We’d had two inches of snow the previous afternoon, but it was too cold for rain. If the body had been left outside in the snow, would it have gotten this wet? Maybe the ME could tell me.

Since I was sure she hadn’t been killed in the barn, I checked the floor for drag marks. The floor was of wooden planks kept so clean that there was no straw or dirt in which drag marks would show, but there were traces of wet prints. Then again, the boy who’d found the body had been in the barn and so had Grady and the uniforms, and me too. I carefully examined the girl’s bare feet. There was no broken skin, no sign her feet had been dragged through the snow or across rough boards.

The killer was strong, then. He’d carried her in here and laid her down. Which meant he’d arranged her like this—pulled up her skirt, splayed her thighs. He’d wanted it to look sexual. Why?

The doors opened. Grady and the forensics team stood in the doorway.

“Blacklight this whole area,” I requested. “And this floor—see if you can get any prints or traffic patterns off it. Don’t let anyone in until that’s done. I’m going to check outside.” I looked at Grady. “The coroner?”

“Should be here any minute.”

“Good. Make sure she’s tested for any signs of penetration, consensual or otherwise.”

“Right.”

Grady barked orders. The crime-scene technicians pulled on blue coveralls and booties just outside the door. This was only the sixth homicide needing real investigation I’d been on since moving back to Lancaster. I was still impressed that the department had decent tools and protocol, even though I knew that was just big-city arrogance talking.

I left them to it and went out to find my killer’s tracks in the snow.

—

This winter had been harsh. In fact, it was shaping up to be the worst in decades. We’d had a white Christmas and then it never really left. The fresh two inches we’d gotten the day before had covered up an older foot or two of dirty snow and ice. Thanks to a low in the twenties, the fresh snow had a dry, powdery surface that showed no signs of melting. It still wasn’t fun to walk on, due to the underlying grunge. It said a lot about the killer if he’d carried her body over any distance.

There was a neatly shoveled path from the house to the barn. The snow in the central open area in the driveway had been stomped down. But it didn’t take me long to spot a deep set of prints heading off across an open field that was otherwise pristine. The line of prints came and went. They showed a sole like that of a work boot and they were large. They came from, and returned to, a distant copse of trees. I bent over to examine one of the prints close to the barn. It had definitely been made since the last snowfall.

A few minutes later, I got my first look at Amos Miller, the Amish farmer who owned the property. Grady called him out and showed him the tracks. Miller looked to be in his mid-forties with dark brown hair and a long, unkempt beard. His face was round and solemn. I said nothing for now, just observed.

They say the first forty-eight hours are critical on a homicide case, and that’s true, but, frankly, a lot of murders can be solved in the first eight. Sometimes it’s obvious—the boyfriend standing there with a guilty look and blood under his nails rambling about a “masked robber.” Sometimes the neighbors can tell you they heard a knock-down, drag-out fight. And sometimes . . . there are tracks in the snow.

“Nah. I didn’t make them prints and ain’t no reason for my boys to be out there,” Amos told Grady. He said “there” as dah, his German accent as broad as his face. “But lemme ask ’em just to be sure.”

He started to stomp away. I called after him. “Bring the boys out here, please.”

Amos Miller shot me a confused look, like he hadn’t expected me to be giving orders. I arched an eyebrow at him—Well?—and he nodded once. I was used to dealing with men who didn’t take a female cop very seriously. And I wanted to see the boys—wanted to see their faces as they looked at those tracks.

My first impression of Amos Miller? He looked worried. Then again, he was an Amish farmer with two boys in their teens. A beautiful young English girl—the Amish called everyone who was not Amish “English”—was dead and spread-eagled in his barn. I’d be worried too.

He came back with three boys. The youngest was small and still a child. That was probably Jacob, the eleven-year-old who’d found the body. His face was blank, like he was in shock. The next oldest looked to be around thirteen, just starting puberty. He was thin with a rather awkward nose and oversized hands he still hadn’t grown into. His father introduced him as Ham. The oldest, Wayne, had to be the fifteen-year-old that Grady mentioned, the oldest child. All three were decent-looking boys in that wholesome, bowl-cut way of Amish youth. The older two looked excited but not guilty. I suppose it was quite an event, having a dead body found on your farm. I wondered if the older boys had gone into the barn to get a good long look at the girl since their little brother’s discovery. Knowing how large families worked, I couldn’t imagine they hadn’t.

Each of the boys glanced at the tracks in the snow and shook his head. “Nah,” the oldest added for good measure. “Ain’t from me.”

“Any of you recognize that print?” I asked. “Does it look like boots you’ve seen before?”

They all craned forward to look. Amos stroked his beard. “Just look like boots, maybe. You can check all ours if you like. We’ve nothin’ to hide.”

I lifted my chin at Grady. We’d definitely want the crime team to inventory every pair of shoes and boots in the house.

“Would you all mind stepping over here for me, please?” I led them over to the other side of the ice-and-gravel drive, where there was some untouched snow. “Youngest to oldest, one at a time.”

The youngest stepped forward into the snow with both feet, then back. The others mimicked his actions obediently, including Amos Miller.

“Thank you. That’s all for now. We’ll want to speak to you a bit later, so please stay home.”

They went back inside and Grady and I compared the tracks. All three of the boys had smaller feet than the tracks in the snow. Amos’s prints were large enough but didn’t have the same sole pattern. Besides, I was sure Grady wasn’t missing the fact that the prints came and went from the trees, since the prints heading that direction overlaid the ones approaching the barn.

“I think Ronks Road is over there beyond those woods.” Grady sounded hopeful as he pointed across the field. “Can it be that easy?”

“Don’t!”

Grady cocked an eyebrow at me.

“You’ll jinx it. Never say the word ‘easy.’ That’s inviting Murphy, his six ex-wives, and their lawyers.”

Grady smirked. “Well, if the killer dumped her here, he had to come from somewhere.”

I hummed. I knew what Grady was thinking. I was thinking it too. A car full of rowdy youths, or maybe just a guy and his hot date, out joyriding in the country. A girl ends up dead and someone gets the bright idea to dump her on an Amish farm. They drive out here, park, cross a snowy cornfield, and leave her in a random barn.

It sounded like a stupid teenage prank, only it was murder and possibly an attempt to frame someone else. That was a lot of prison years of serious. A story like that—it would make the press happy and Grady fucking ecstatic, especially if we could nab the guy who wore those boots by tonight.

“Get a photographer and a recorder and let’s go,” I said, feeling only a moment’s silent regret over my good black leather boots. I should have worn my wellies.

—

It wasn’t that easy.

The tracks crossed the field and went into the trees. They continued about ten feet before they ended—at a creek. It hadn’t been visible from the barn, but there was running water here, a good twelve feet across. The land dipped down to it, as if carved out over time. The snow grew muddy and trampled at the creek bank. The boot prints entered the water. They didn’t reemerge on the opposite side.

“Cattle use this creek?” I asked Grady, looking at the mess of mud and snow and hoofprints along the bank.

Grady sighed. “Hell. It’s not legal, but a lot of the farmers do it, especially the Amish. It’s hard to explain to a man whose family has farmed the same land for generations why politicians in Baltimore don’t want his animals to have access to the free and plentiful water on his own land.”

I really didn’t give a toss about the pollution of Chesapeake Bay at the moment. But our possible killer’s footprints, so clean in the snow, had vanished into a churned-up creek bed that had been literally ridden herd over. I walked up and down the bank as carefully as I could, trying not to step anywhere there might be evidence. There was chicken wire strung up across the creek to the north, and a matching wire wall glinted to the south. Presumably, this kept the farm’s animals from escaping the property.

The freaky thing was, there were no signs of tracks on the other side of the creek anywhere between those two makeshift fences. I rubbed my forehead, a sense of frustration starting in my stomach.

“Damn it!” Grady cursed, apparently reaching the same conclusion.

“How far is the road?” I asked.

As if to answer my question, an SUV lumbered past, visible through the trees on the far side. There was a road maybe thirty feet beyond the other side of the creek.

In a righteous world, the boot prints would have climbed out the opposite bank and led right to that road. In a righteous world, there’d be tire tracks off the side of the road over there, tire tracks we could attempt to trace.

No one had to tell me it wasn’t a righteous world.

I looked at the creek again, then went back to look at the boot prints. The prints with the toes facing the creek definitely overlaid the prints with the toes facing away. Unless the killer had walked backward in both directions—one way carrying a dead body—he hadn’t come from the farm.

Grady stood there shaking his head. I decided, Screw it, and shucked my boots and rolled up my pant legs. At least this suit was a trendy wash-and-wear and didn’t require dry cleaning.

“You don’t have to do that.” Grady sounded uneasy.

I ignored him. If there was one thing I knew for sure about being a woman on the police force, it was that you didn’t turn up your nose at getting physical or messy. You didn’t wait for some guy to do it. If you wanted respect, you had to be willing to jump into the shit headfirst.

But, goddamn, this sucked. I waded into the ice water masquerading as a creek and followed the bank to the chicken-wire obstruction.

“Anything?” Grady called to me as I ran my hand along the chicken wire and stepped deeper into the creek.

When I reached the middle, the frigid water was streaming painfully around my upper thighs.

“Damn,” I muttered as I felt along the fence.

A few inches below the surface of the water the wire ended. To be sure, I sent one leg forward on a foray. It swept through nothing but water. No wonder our Jane Doe had gotten wet. The killer had pushed her under these barriers and then likely followed by ducking under himself.

“Bastard walked through the creek,” I said, my voice shaking with cold and not a little disgust. “He came in and out under one of these fences, but he had to leave the water somewhere. We need to search the banks upstream and down from here. We’ll find his tracks.”

I sounded confident. And I did believe what I was saying. We were talking about a man, after all, not a superhuman, not a ghost.

I was wrong.

CHAPTER 2

Fistful of Seeds

I sat at my desk and stared at the situation board I’d set up right behind me. The mug in my hands was warm, but its heat ended where porcelain met skin. Nothing could penetrate the chill I lived with. It was psychological, or so my therapist had said, the one they made me see after what went down in New York. That didn’t make it any damn less unpleasant.

Always so cold, deep down inside. Moving back here to a simpler life was supposed to change that.

The property survey map in front of me had been marked up with permanent pens and Post-it notes. It’d been only twenty-five hours since I’d pulled up to that barn yesterday in the predawn hours to get my first look at Jane Doe. By now I knew this case wasn’t going to be one of the quick ones.

The teams had crawled all over the countryside yesterday. Grady even called in reinforcements from Harrisburg. We’d carefully gone up and down that creek bed for several miles in either direction. The killer’s tracks never emerged from it.

Which led me to one inescapable conclusion, and I’d marked it on the map.

As for our Jane Doe, we hadn’t found her coat and shoes. The coroner was almost certain her death was caused by asphyxiation. The autopsy would reveal more. The time of death was a bit of a surprise—between ten the previous morning and four in the afternoon, depending on how long she’d been in the cold water. And we knew she’d been moved to the barn most likely between midnight and two A.M., giving her clothes and hair a chance to mostly dry before Jacob found her at five.

It was still dark outside, but there were rousing sounds of life in the sparkling new facility that was the Lancaster City Bureau of Police. I saw Grady in my peripheral vision. Like me, he’d gone home after midnight and was back before dawn. He wheeled over a roller chair and planted himself next to me, a mug of joe in his hands. He yawned hugely, making no attempt to cover it up. I smiled to myself. I appreciated the fact that Grady treated me like one of the guys. And I liked his wife, Sharon. The wife of the last partner I’d had in New York had hated me at first glance and was always going into jealous rants on the phone when we had to work late. But Sharon was a petite, redheaded spitfire whose passion was the LGBT youth center in Lancaster. She and Grady had three boys and they were solid. They’d had me over for dinner a few times. Sharon didn’t find me a threat.

Detective Lieutenant Mike Grady wasn’t my type anyway, even if I’d been into home wrecking—which I wasn’t—even if I’d had any interest in sex at all since Terry died—which I didn’t. Grady ran the Violent Crimes Department for the Lancaster City Bureau of Police. He was in his late thirties and, like many Pennsylvania men, he was big—six foot two and at least two hundred fifty pounds. He’d probably played football or wrestled in high school. He had short, curly brown hair, beefy hands and shoulders, and a reddish complexion. A lot of years behind the desk and serious home cooking had given him a belly and bulky heft all over. Grady was a nice guy. Then again, most people who lived here were.

I was from here originally too, but my “nice” had been hammered down by ten years of being a police officer for the NYPD. I had to be tough because a) I was a woman and b) I had a tall but somewhat fragile build and a pretty face to overcome. Everyone thought I was crazy when I decided to join the police academy. I’d never been a natural jock. But I liked that—liked the fact that it was something that really challenged me, that I was going against type. I loved being sweaty and tough. I’d worked my ass off, trained hard then—and still did. No perp was going to take advantage of me, and no fellow police officer either. I wore my dark hair pulled back in a bun and little makeup to work. That didn’t keep men from being, well, male, but most of them knew better than to treat me like a dumping ground for their hormones. At least they did after the first time they tried it.

“No matches in missing persons,” Grady said by way of greeting. “Today I’m sending Hernandez and Smith out to talk to all the high school principals in the area, show them her picture. And we’ll send out a missing persons bulletin to all the Mid-Atlantic precincts. If we don’t get an ID on her today, I’ll have to do a press alert.”

I hummed. I knew a press alert was the last thing we needed. I was surprised the story had been kept quiet so far. We’d been lucky that the area where the farm was located was well off the beaten track.

“I want to interview everyone at those farms today,” I said, nodding at the map.

Grady sighed. He was silent for a good while as we both regarded the layout. “Talk to me, Harris,” he said in a tone that acknowledged that he wouldn’t like what I had to say. “What are you thinking?”

I stood up and drew my finger down six lines I’d drawn with a brown pencil. Each one ran from the creek—which we’d since learned was called Rockvale Creek—to the farms. The lines were on the Millers’ property and five of their neighbors’.

“The killer used one of these animal trails to get in and out of the creek. Had to. We didn’t find his prints leaving the creek because they were trod over at some point after he left her body at the Millers’, covered up by hoofprints.”

I looked at Grady. He was frowning, but he didn’t say anything.

“We saw dairy cows out in a couple of these fields yesterday.” I tapped two Post-it notes I’d put up with cow stick figures. My attempt at high art. “So for sure he could have used either of these trails. As for the others, all these farms have at least a horse or two for the buggies. We’ll have to interview the farmers to know if their animals were out between midnight and when we were looking, I’d say as late as ten A.M. yesterday.”

“He could have kept to the creek. Could’ve walked miles,” Grady countered.

“Even in the water, it wouldn’t have been easy to manage a dead body, and it was damned freezing. Plus, we looked up and down both banks of the creek and didn’t find fresh prints coming out of it for at least a mile. And there aren’t any more animal tracks along it for a good ways either.” I tapped the paper. “He used one of these trails, Grady. Which means he knows this place. He knew where those trails were and when the animals moved. He came from one of these farms.”

It was the first time I’d said it out loud, but I’d started thinking it yesterday afternoon. I knew Grady didn’t want to hear it. Then again, I didn’t want a lot of the shit that had happened to me. Life sucked that way.

Grady rubbed at his jaw. He looked around as if worried about being overheard. But most of the detectives didn’t get in until after seven. He still lowered his voice.

“Okay, I agree that he knows the area. That doesn’t mean he’s Amish. He could be someone who works with the Amish—a driver, someone who picks up dairy or produce. Hell, a mailman. Or a customer.”

He grabbed my Post-it pad and began scribbling. He tore off the top page and slapped it over one of the properties marked Fisher. “Eggs and dairy,” he said, repeating what he’d written on the note. He scribbled another one and put it on the map. “Chicken coops.” Another. “Baked goods.” Another. “Mules.” He waved his hand. “All these farmers sell goods directly off their farms, which means they have customers driving in and out all the time. Any of those customers could have thought, Gee whiz, where should I dump this body? How ’bout where I buy my eggs? No one would ever guess because I’m such a clever bastard.”

“Just because you stop in someone’s driveway to buy eggs doesn’t mean you can see the creek or the animal trails leading to it. The creek’s in a gully.”

“Maybe they wandered around a bit one fine spring day. Maybe their dog took off across a field and they chased it. Maybe they chatted with the farmer and he mentioned it. Could have been months ago, even years, and only now they had a reason to use that information. Hell, it could have been a fisherman or hunter who wandered up and down that creek in his youth. These farms have had cows and horses living there for a hundred years, which means those trails have been there forever.”

He had a point. Maybe I was getting ahead of myself. “Right. We should get started on customer lists, and lists of anyone who visits these farms regularly. But . . . I’m gonna say this, Grady, at least once.”

I waited until he looked at me.

“I’m not ruling out anything, not yet. These farmers and their families have to be considered suspects, at least until we can cross them off officially.”

I made it sound logical, but it was more than that to me. It was a gut feeling, a feeling that said the killer knew this area like he knew his own skin.

Grady’s frown deepened. “Look, Harris, I hired you because you’ve got the best homicide training from one of the biggest cities in the world. So I’m glad I have you available for something like this.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...