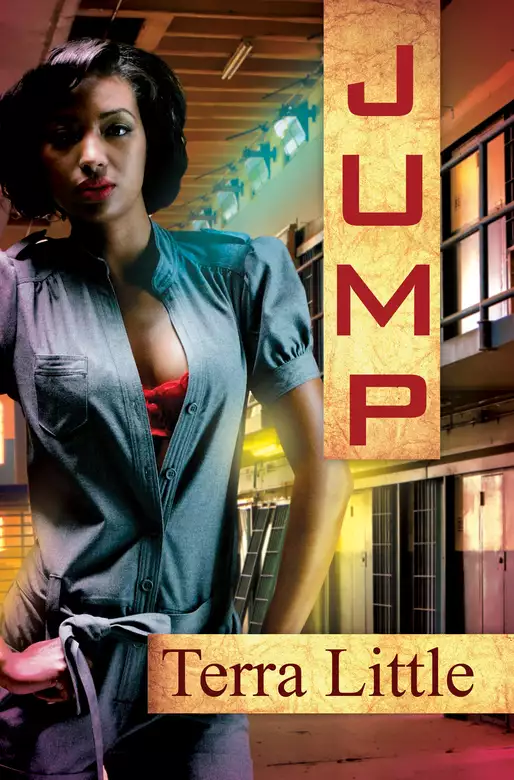

Jump

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Killing her grandmother was a choice Helena Hunter made all by herself, but she wasn’t thinking about the consequences of her actions when she pulled the trigger. Back home after eight years in prison, she finds that the little girl she left behind is now a teenage stranger who thinks her mother might be a monster. The family members who labeled her the black sheep want her to forget the fact that they all played a part in her downfall. And the wonder of being free again is overshadowed by the fear of a future filled with uncertainty.

Shaking the stigma of incarceration proves to be more than Lena bargained for. Before her life went to hell, she was a middle-class computer geek and a proud parent. Now that she’s been labeled a menace to society, she is a walking, talking poster child for what can happen to victims who take the law into their own hands.

Experience is the best teacher, though, and whatever lessons Lena hasn’t learned, she soon will—from the most unlikely sources. Complete freedom is possible, but only when the truth is finally revealed and the ghosts from her past are exorcised.

Those brave enough to step into Lena’s world will be left asking themselves one burning question: “What would I have done?”

Release date: June 8, 2011

Publisher: Urban Books

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Jump

Terra Little

I don’t really remember putting the gun in my purse before I left my apartment. I don’t remember consciously digging it out in the heat of the moment, aiming it and pulling the trigger. All I know is that I did.

I do remember watching her body fall to the floor and take its last breath. I remember those eyes, focused on my face in a way they never had before, silently accusing me of losing my mind. And maybe I did lose it for a moment. At least that’s what my public defender told the jury. That I had been temporarily unstable, incapable of making rational decisions at the time of the murder. He came up with that brilliant defense after I told him I had been tripping out on Ecstasy and tripping bad. It was ultimately what kept me from earning myself a murder one charge, and for that I guess I should consider myself grateful.

One after another, people who thought they knew me took the stand and testified that I had not been a drug user before—not to discredit me, though the prosecutor worked that angle, but to help me prove that I was a neophyte, ill-equipped to handle the side effects of a sneaky drug like Ecstasy. Supposedly, I didn’t know what I was getting into when I took the pill and I didn’t know what I was really doing when I pulled the trigger. It was my first time experimenting with drugs, and now I was a poster child for just saying no.

But the thing is this: I knew.

Is there a drug in existence, in the entire world, that can numb the mind and the heart so much that you don’t realize you’re aiming the barrel of a pistol at your grandmother’s heart?

I don’t think so, and the jury didn’t either.

A female voice accepts the collect call that I tell the operator to put through to Vicky’s residence. I wait as the phone rings and then I catch my breath when I hear a voice on the other end. It’s not my sister’s and I know whose it is, but I say nothing about who I am. I ask for my sister and wait for her to come on the line, listening to the sounds of her house in the background and wondering what it’s like where she lives. I used to know, but I don’t anymore.

There is a loud television blaring in the background as she puts the receiver to her ear. “Bey, turn that thing down, okay? I can hear it all the way in the basement,” Vicky takes a moment to call out. Then, “Hello?”

“Vicky, it’s me, ” I say.

Her voice sounds strange to me, like I’ve forgotten the way she talks, the way she ends every sentence on a high note and sounds like she is asking a question instead of making a statement.

“Oh.” She sucks in air through her mouth and I can almost see her bottom lip dragging the floor. She is surprised I’m calling. I know because the air she releases hits my eardrum like a hundred stomping feet in a hurry to reach their destination. “Lena. Hi.”

“The parole office called you, right? You know I’m getting out tomorrow?” I’m curled around the pay phone, trying to talk low so my conversation is semi-private because completely private is out of the question. You hear everything, one way or another, in prison. Behind me, another inmate pushes up close to me and slips her arms around my waist, and I know semi-private is out of the question too. She presses a soft kiss to the side of my neck and then her lips drift behind my ear. She wants my attention, and I do my best to ignore her.

“She said to tell you that you have to report to her first thing. Soon as you get here,” Vicky informs me, talking just as low. “She came by here a while ago and left her card.”

I listed Vicky’s address as the place where I will live after my release. I didn’t think she’d actually agree to have me living in her house, but it was worth a shot. Now that I know that’s where I’ll be going, I don’t know how I feel about actually living there. “You told the parole officer it was okay,” I remind her because she isn’t sounding too sure and now is not the time for her to pull some bullshit. If she changes her mind, I’m going to a halfway house, which is just like being in prison—which kind of defeats the purpose of getting out.

“Yes. I did tell her that.”

I push at the arms gripping my waist, shoot an irritated look over my shoulder and feel them loosen slightly. I was curled around the phone like a parenthesis a few minutes ago, but now I’m looking more like an interrobang, a question mark and exclamation point combination. “Did you change your mind?”

“No, Lena, I didn’t change my mind. What time will you be released?”

She wants to cry. I can hear it in her voice and I hate the sound of it. I haven’t had much use for tears in a long, long time. “Ten o’clock,” I tell her, harsher than I really mean to be, so she’ll know to swallow the lump in her throat. “More like eleven by the time I get myself together. The bus doesn’t get there until sometime after five though.”

“They’ll put you on a bus?”

“Roadway Bus Lines.” I pause as an automated voice tells her that the call originates from the Dwyer Correctional Facility for Women. “Should be there by five-thirty. I can take a cab from the bus station.”

“No!” Vicky damn near shouts in my ear.

“No, don’t take a cab or no, don’t come?”

“Don’t take the bus. Don’t let them put you on a bus, Lena. I . . . we . . . we want to come and get you. Do they allow that?”

“I’m three hours away.” I haven’t had a visitor, live and in the flesh, in over five years.

After the novelty wore off, they stopped coming. And I haven’t seen my daughter, Beige, in over eight years. She is the we Vicky mentions, and the we knocks me in my face and sends me back a step.

“We can leave early in the morning and be there by ten.”

“We can save some gas and pick me up at the bus station.”

“You act like you don’t want to see us.”

I start to tell her that she has a lot of nerve saying that to me, but I don’t. I catch myself just before I remind her that she hasn’t visited me once in all the years I’ve been here. Not once. I guess she had her reasons for not coming, just like I have mine for not wanting her to come now. “I don’t,” I admit softly. “Not like this. Not . . . Look, if you have to come, don’t bring her. She doesn’t need to see this place and me in it. This is no place for a kid, so leave her, okay?”

“It’s not like she doesn’t know where you are. Plus, she’s fourteen, Lena. Almost fifteen.”

Like I don’t know. “She’s a kid and kids don’t belong here.” Vicky doesn’t know what I know and she never will. If she brings my daughter to this place, the stink of it will seep into her skin and leak out of her pores for the rest of her life. No soap in the world can wash it off. “If you come, don’t bring her.”

“I’m coming, Lena. I just—”

“Don’t bring her,” I cut her off. “Eleven o’clock.”

Then I hang up.

Family portrait:

Lou is over six feet tall and solid as a rock. She has skin the color of tree bark and none of us is exactly sure how old she is. She has told us all different ages on purpose, to keep us guessing and in our places. Children don’t question their parents about things that are none of their business, so be seen and not heard, Lou likes to say. With my eyes wide open and clearly focused on her round face, I still manage to see with my heart. I don’t see what is obviously a woman. I see Lou, who is the head of our family. Our father.

Denny is mama. Denny, with her gentle hands and long, silky hair. There is a wide streak of gray that snakes through it, like the bride of Frankenstein, and it is that streak that mesmerizes me when I am fortunate enough to have the pleasure of taking a comb to her scalp and scratching it for her. Unlike Lou, the years she has spent in captivity are etched on her caramel-brown face. Twenty-six so far and still so many to go. She pretends to be happy that I’m leaving, but in her eyes I see what she won’t allow her lips to say. Denny’s children were still babies when she did what she did to bring herself here, and they are all grown now. They don’t come to visit and only one of them takes the time to write. In her mind, she is losing another child.

There are three of us children who belong to Lou and Denny; I am the youngest, though not in age. I was the last to join the circle, like a change of life baby, and after me, Lou and Denny decided they are done having kids. They had probably decided this before I came along, but after Lou found me in the shower room, abandoned with a symbolic note pinned to my ass and no one to claim me, she brought me home anyway.

On my last night here, I divide the few things I have accumulated in eight years’ time between the women who are like my sisters. I give them the books that have kept me sane through the years, read cover to cover so many times that tape keeps the covers attached, and the few luxuries I have allowed myself. A small boom box and cassette tapes that I’m not supposed to have in my possession. I give one of them a sweater that she always coveted, and I spend hours braiding the other one’s hair. She wants it this way and that way, parted here and there. I listen carefully and style it exactly the way she tells me to because I will miss her the most.

We cry. Even though Lou is dad and Denny has been through enough that her tears should have long been exhausted, we cry. Here in this place where none of us are really considered women, we cry like women. We are numbers with two-letter suffixes, and we are called animals and treated as such because we have done things to bring that label on ourselves, but we still cry. We sit up late into the night, passing a bottle of whiskey around, sipping slowly, passing our memories around even more slowly, and continue soaking each other in—for the last time. I am the one who is leaving the fold, so I cry the hardest.

I have to, because in the morning things will be different. They will have shut me out. I know it and I accept it, and I don’t admit to myself just yet that I welcome it. It’s hard to be happy about leaving my family behind.

The guards see what they want to see and pretend not to see what they don’t. They don’t see that none of us is where we are supposed to be after lights out. They don’t see the contraband we pass around and they don’t hear the sound of our voices as we talk and laugh and cry.

They don’t see me in the middle of the night, holding still another woman as she cries as if the world is coming to an end. There are two others who belong to Lou and Denny, and both of them I will miss, but there is another woman I will miss too. As I hold her, we don’t talk, and I don’t let myself think about what I will miss the most. I wonder who she will love after I am gone and who will love her. I wait for jealousy and possessiveness to come, but they don’t, and I know I am slowly wrapping myself around the idea of freedom.

Though we roam around the quads like unrestrained animals in a petting zoo much of the time, there are protocols to follow and rules to obey, when the people who matter are watching. The guards who pretend to be blind suddenly have sight. They remember that we are just numbers and that they have families of their own, families who count on their steady paychecks. Those of us who have learned this lesson early on know what is what and when is when.

As the sun comes up, I fall back into the role of inmate number 1250TN. I keep my eyes on the floor, I take the manila envelope containing the property I don’t remember owning when I came here like I am grateful to have it, and I let myself be led meekly to the last stop. Jackie, a night shift guard, doesn’t wish me luck, even though I kick her ass in Gin Rummy regularly and she has shown me pictures of her kids. I tell myself that I’m not offended by the fact that Tony, a swing shift guard, doesn’t meet my eyes, even though I have stayed awake more than a few nights reading passages from what he hopes will become a best-selling novel. It’s like they don’t know me, like they don’t give a damn that I’m leaving, and it hurts.

I want them to tell me they will miss me, that I have meant something to them, but they don’t. I wait for them to impart last words of encouragement before the door, separating me from freedom, is opened and I am shoved out of it, but no words come. It’s like I have never existed, like they want to forget they knew me.

I am so lost in my feelings of rejection that Tony’s hand on my back doesn’t register until he uses it to push me forward. I trip over my own feet, grab a chair in the waiting area to steady myself, and look back at him with fifty questions in my eyes.

Then I see it. A hint of a smile and traces of humanity in his eyes. He tells me, “And stay out,” and then I get it. They don’t want to remember that they knew me. They don’t want me to miss them so much that I want to visit them here again. They don’t want me to come back.

Something tickles my memory and I feel like giggling. Me and Vicky are kids again, partners in crime like only sisters can be, and we have devised the perfect plan. Mama is working and we are stuck in the house waiting for time to pass. For us, summertime doesn’t officially begin until Mama comes home from work and we can escape to the outdoors with all the other kids. Mama leaves us by ourselves in the daytime, which is illegal, so we have to stay indoors until she comes home. We don’t touch the stove, we don’t answer the phone, and we don’t open the door, no matter who it is.

I think the sun rises and sets on Vicky. She is the oldest and, therefore, smarter than I can ever hope to be. She convinces me that we can go outside to play with our friends and then come back inside long before Mama comes home from work. She’ll never know we were outside, Vicky says, and I believe her. She pushes the house key deep in her pocket, takes me by my hand and off we go. I don’t stop to remind her that she doesn’t use the key to lock the door behind us. I see my best friend farther down the street and I am anxious to be down there with her. She has a Farrah Fawcett hairstyling head that I love to play with, and that is all I can think about at the moment.

Vicky is seven and I am five when Mama comes home and finds out that we no longer have a television or a hi-fi. Some of her clothes are stolen too, and she curses for hours about that. She says words I have never heard before when she sees that her record albums are gone. She beats the shit out of me and Vicky for leaving the house in the first place. She cries the longest over her photo albums, and finally drags herself off to bed, mumbling under her breath about our baby pictures being gone. “Who would steal pictures of my babies?” she wants to know.

The police aren’t called, and I know it’s because Mama would have to explain why we were left alone in the house to begin with. Someone might start asking questions that she can’t answer, and she is too angry and disappointed to think up plausible lies.

We did it to ourselves. If we had just waited a few more hours, until Mama came home, she wouldn’t have had to pick up the phone and call my grandmother on the scene. We go from the comfort of our own home to my grandmother’s house, which smells like old lady and something else that I can’t quite name. We get dropped off every morning and picked up every evening, and I hate it like I hate the homemade caramel and brownies my grandmother always bakes and makes us eat.

It doesn’t take me long to realize that Vicky isn’t as smart as I think she is, and it takes me even less time to come to the conclusion that we have made a big mistake. I don’t think Mama ever really forgave us for being so stupid, and I don’t even have to think about forgiving Vicky to know that I haven’t. Like a lamb to slaughter she led me, and she was supposed to know better.

Vicky’s arms surround me now and I smell her scent. It takes me back in time to a place I don’t want to go. It takes me back to the claustrophobic little house my grandmother lived in, to the depths of her bedroom, where she kept an endless supply of White Shoulders perfume on her dressing table. It was her signature scent, and now it is Vicky’s.

I catch myself before I open my mouth to tell her that her shoulders aren’t white and the scent makes me want to puke. Instead, I hug her back and say, “Hey.”

She pulls back and looks at me, sees that I don’t have a relaxer anymore, that I have lost weight and gained muscle mass, and bursts out crying. I lift my locks from my shoulders and feel air on the back of my neck, watch her and wait. I won’t hold her as she cries, won’t offer her even a little bit of comfort, because I don’t have it in me. She hasn’t come to visit me in eight years and I don’t know why. What I do know is that she wouldn’t be so shocked by the sight of me if she had.

“Eight years is such a damn long time,” she says when she can talk.

I catch her eyes and smile. “You know better than me. I owe you, what, about a million dollars and some change?” She put money on my books faithfully, kept me from having to beg, borrow or steal to survive.

We stare at each other. If I have changed, she hasn’t. She still wears her hair long and straight, relaxed to death and hanging down her back. Still plucks the hell out of her eyebrows and lines her lips with a dark pencil before filling them in with bright lipgloss. She still looks like a deer trapped in the glare of highbeams, poised to run for her life at the slightest provocation. I wonder if she is poised to run from me and everything I represent.

“You look good, Vicky,” I offer.

“You look . . .” She raises her hands, shakes her head and lets them drop. “Different. Damn, Lena. What do you press, a thousand pounds?”

She reaches out and squeezes my bicep lightly, looking awed. She is exaggerating, but I let it roll. I don’t look anything like those tennis star sisters and she knows it. Smooth and tight, maybe, but nowhere near as buff. I’m working on it though.

“Just a couple hundred,” I say. “Give or take. Can we get the hell out of here?”

My question catches her off guard, snaps her out of her thoughts and reminds her of where we are. “Oh! Um . . . yeah.” She looks at the envelope I’m holding. “Is this all your stuff?”

“Everything else belongs to the state.”

My eyes go everywhere at once as I follow her out to her car. She is driving a shiny red machine, something sporty and compact, and I like the look of it. I give the leather seats and complicated-looking dashboard cursory glances, and then I take my eyes back to the sky, where they really want to be.

I like the look of the sun even better, love the feel of fresh air on my skin. I can’t get over how much brighter the sun seems and how much lighter the air is on the outside. As we drive off and pick up speed on the interstate, I push a button to lower my window. I stick my head out and let the wind snatch my breath, stick my tongue out and taste freedom. Vicky is right; eight years is a long time.

She catches me darting glances around her house and answers my question before I ask.

“She won’t be home until later,” Vicky says, referring to the person I most want to see and then again don’t really want to see at all. “Around seven or eight, I think she said.”

“She sets her own schedule?” I look around the room she shows me, in the rear of the basement, not far from the washer and dryer. Just outside the door is a carpeted sitting area, a big screen television and a treadmill. I look past her to the door, and see that it has a lock on it. I meet her eyes after it occurs to me that she hasn’t answered my question.

“She decided to hang out with a friend. Maybe stay for dinner.”

Vicky can’t look at me. She does things to make herself busy. She straightens the covers on the bed, smoothes a hand over a pillow, and then adjusts the rug on the floor with the toe of her shoe. I wait for her to break out in a song and dance routine to kill even more time, wondering if she really thinks she’s being subtle.

She is my daughter. The only child I have and the only one I will probably ever have. The one I spent seven hours of my life bringing into the world, and the one I haven’t seen in eight hellacious years. The one who doesn’t care that I am home. She doesn’t want to see me, or maybe she isn’t ready to see me. Either way, she isn’t here, and Vicky being unable to look me in my face tells me more than I want to hear. I am hurt, and the feeling comes at me from out of nowhere, surprises me because hurt is something that I haven’t felt in a long time. But I don’t let my face bear witness.

“I guess she has to eat,” I say.

“She wants to see you, Lena.”

“I know.”

“She just needs some time to adjust to you being home. It’s been—”

“Eight years. I know that too.” I point to the small closet across the room. The door is open, and inside I see boxes stacked against one wall. Three of them. My handwriting crisscrosses the cardboard like a crossword puzzle I designed when I was drunk. Letters are jumbled together, scratched out and connected by thick dashes, making it impossible to guess what’s inside. Might’ve been pots and pans at one time, and towels and sheets another time. Could be anything now.

“You saved my old moving boxes?”

“I saved your clothes,” she says, moving past me to drag a box from the closet to the middle of the floor. “I found the boxes in a closet in your apartment . . . after you were already gone.” She reaches inside and hands me a neatly folded nightgown that I immediately press to my nose, searching for a familiar scent. I find it and inhale deeply; my eyes close. “There’s another box somewhere with shoes in it. I’ll have to look for it.” A smile touches her lips. “I wore some of them.”

“The black slingbacks you always wanted?”

“Wore them.” We laugh.

“The red stilettos . . .”

“Wore the hell out of those too.”

“I think they were yours anyway.” I sit on the bed and slide the box closer, dig in and sigh as I find several pairs of panties and matching bras. I was prepared to wash the ones I have on every night and recycle them, until I can get my hands on the money to buy more. It doesn’t even matter that the ones I find in the box are a size too big or that my breasts could fit in the cups of the bras twice and still have room to breathe. “Thanks for saving this stuff. I need it like you wouldn’t believe.”

Vicky looks lost in thought for a moment. “All of your other stuff . . . we didn’t know what to do with it. I wanted to save it too, but—”

“Didn’t have much anyway,” I say, letting her off the hook on which she hangs herself. Another day I will ask her for specifics. Who got what and what happened to this or that thing, but today I can only handle so much. For now I’ll live with the lie.

I had furniture and household gadgets. A toaster and a blender that overheated and filled my apartment with the smell of burning rubber. I had a color television that I paid for over time and a VCR, which was high-tech back then. I had a stereo system with speakers almost as tall as I am, albums and cassette tapes, movies on VHS and a wicker basket where I kept spools of thread and needles for when I needed to replace a button or hem pants. I had books that I always swore I would die trying to save if a fire broke out. I had a top-of-the-line computer system that was like a second child to me.

I had a life and now I have nothing. Not even a daughter who cares enough to welcome me home.

Vicky asks me if I need anything else and I tell her that I don’t. I watch her back out of what is now my room and pull the door closed behind her. After she is gone, I unpack the boxes and take stacks of clothes over to the armoire. I pull out drawers and spend endless minutes trying to decide what goes where. I used to have a system; now I can’t remember what that system was. Underwear and socks in the top drawers or the bottom ones? Shirts and sweaters mixed together in the same drawer or separately? Night clothes on the left or the right?

The dilemma stumps me, sweeps my mind clear of any and all thought. I can’t understand what my problem is, why my mind won’t cooperate and make things easy for me. I am not a dumb person, I remind myself. I have a degree in information technology, though I have no idea where it is at the moment, and this isn’t advanced calculus. Something this simple shouldn’t require this much thought. So what is my problem?

Disgusted with myself, I leave the clothes sitting on top of the armoire and push boxes out of my way with my feet. I drop to the floor and lay on my back with my arms crossed over my chest like I’m in a casket. Inside, I was number 1250TN and here on the outside, I am still number 1250TN. My mind has no problem remembering that.

I start to do crunches, a hundred and twenty-five in sixty seconds. I flip over to my stomach and do just as many push-ups, wishing there was a bar bolted to the wall or free weights sitting around for me to use. I can lift a hundred pounds in one hand like it’s nothing, and before I got out, I was trying for a hundred and twenty-five.

When I feel beads of sweat popping out on my forehead, I sit up and lean back against the bed, and stare across the room at the clothes I don’t know what to do with. Then it comes to me slowly but surely. I realize I have encountered my first obstacle.

I have to learn how to make decisions for myself all over again.

They put me in a cell with a deranged-looking woman named Yolanda. She tells me to call her Yo-Yo, if I have to call her anything at all. She likes silence, she says, so could I please keep my mouth shut as much as possible? I look at the elaborately designed braids wrapped around her skull, the scar that stretches from her ear to the corner of her mouth, and wonder what she did to make someone do that to her. Then I decide I don’t care one way or the other as she trains deep-set brown eyes on me and stares like a heathen. There are dark circles around her eyes and they are slightly misaligned. I come to the conclusion that she is more than a little touched in the head, and the confines of our cell suddenly seem smaller.

“Yo’ ass got the top bunk.” She leans against the wall with her arms crossed over her chest, taking me in from head to toe. Matching purple prison scrubs and thin-soled cloth sneakers make us twins, but that’s where the similarities end. “That’s all you got in here, too. Squatter’s rights, girl. Don’t shit in here belong to you but that space up there.” She points at my bunk and then she uses the nail attached to the finger to pick her teeth. “Everything else in here belongs to me.”

I climb up to my bu. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...