- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

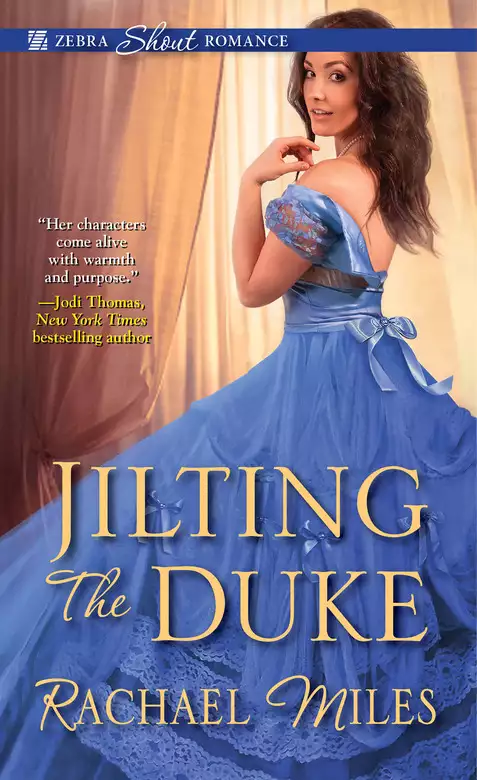

Synopsis

Aidan Somerville, Duke of Forster, is a rake, a spy, and a soldier, richer than sin and twice as handsome. Now he is also guardian to his deceased best friend’s young son. The choice makes perfect sense—except that the child’s mother is the lovely Sophia Gardiner, to whom Aidan was engaged before he went off to war.

When the news reached him that she had married another, his ship had not yet even left the dock. Sophia does not expect Aidan to understand or forgive her. But she cannot allow him to stay her enemy. She’s prepared for coldness, even vengeance—but not for the return of the heedless lust she and Aidan tumbled into ten years ago. She knows the risks of succumbing to this dangerous desire. Still, with Aidan so near, it’s impossible not to dream about a second chance.

Release date: February 1, 2016

Publisher: Zebra Books

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Jilting the Duke

Rachael Miles

Who murders a dying man?

Aidan Somerville, Duke of Forster, pulled loose the tight knot of his cravat. News of Tom Gardiner, Lord Wilmot’s death had arrived in London the preceding fall. But even after a year, Aidan had no answers, just suspicions. He only knew that he had failed his old friend—and continued to fail him—in not avenging his death.

The streets were dark, illuminated at intervals by the dim light of street lamps low on oil. It was reckless to walk London streets alone after midnight. But the walk was short—no more than half an hour if he took the path across the park—and it couldn’t be helped. He’d sent Fletcher and his coach home hours ago.

From the darkened alleyway ahead of him, Aidan heard muffled sounds of movement, and he stepped into the shadows. Waiting to see what trouble emerged, he wished—not for the first time—that he hadn’t gone to Lady Belmont’s salon. Her invitation included more than witty repartee, but he had felt nothing, not even male pride, when she’d let her hand linger too openly on his. And nothing later, when at dinner—during a rancorous debate on currency and the bank question—she had slipped a nimble foot up the inside of his thigh, then asked coyly whether he took pleasure in “the increased movement . . . of foreign markets.” Lady Belmont would have laughed if he had confessed that a dead man haunted his dreams. She would have turned it into a provocative game: “Ah, then, let us undress each other, my pet, and we will chase away the night until it is day.”

Listening, he moved his hand midway down his walking stick; the solid brass knob on the strong ebony made an elegant weapon. Another sound, closer. He would feel foolish to come up dead after living through the worst campaigns of the Peninsular War. But perhaps his grave would be quiet, quieter at least than Tom’s. Aidan tightened his grip. Another low sound, just beyond the entrance to the alley. He tensed, a seasoned soldier ready for battle.

From the alley, a large red fox trotted into the light. Aidan caught back a laugh. An old soldier alarmed by a fox. As the animal disappeared into the dark on the other side of the street, Aidan continued past the alley toward the park, his thoughts returning to Tom, a man so ill no one had expected him to live out the year. Others might think it a natural death, but Aidan knew it had been murder, just as surely as he knew who had done it.

Tom’s wife. Sophia.

The thought of her name twisted like steel in his chest. Even now, after the separation of a decade, her name still evoked desire and the memory of the supple warmth of her body taking him in. He felt her betrayal as a cold mass below his diaphragm, impeding his breath. If he could discover proof of Sophia’s treachery, he could avenge them both, himself and Tom. Yet despite Aidan’s inquiries, he knew no more than he had a year ago. He quickened his pace, as if exertion could exorcise his guilt, then crossed into the park.

The night was beautiful, cool, with a hint of the evening rain still in the air. But the scent of something else, something heavy and florid, drew him into a section of the park lit only by intermittent moonlight. He knew the path well, for he often walked it when sleep wouldn’t come. It undulated gently along the side of the park, curving against the open iron fence separating the park from the street in front of his house. Each bank of shrubs concealed the next section of the path, and he always liked the surprise of reaching the end of one bank to suddenly gain the vista of the next.

In the first section, banks of flowers, blooming white in the night, escaped their beds and crowded the path. Ipomoea. Without thinking, he remembered the flower’s proper name, and—without wanting to—Sophia’s hand warm in his, teaching him the names of the night-blooming flowers as they walked through her uncle’s gardens.

Name it right, and I’ll give you a kiss.

Will you not kiss me if I name it wrong?

You’ll have to name it and see. But I’ll tell you a secret: If you drink in the scent when it blooms, like now, you’ll have visions and dreams while you sleep. And they always come true.

I don’t need dreams. I already have you.

Then he had kissed her, naming all the flowers by their botanical names in a line from her lips, down her neck, and to her breasts, and back to her mouth, until her kisses, sweet against his lips, turned mad with longing. In his youth and inexperience, he’d mistaken her fervor for love.

He pushed the memory away. Had he taken her advice and slept, not in her arms but in the scent of the flowers, he might have known she would betray him. Instead, the wound she’d struck festered still, leaving him a future as bleak as his past.

The moonflower’s scent was delicate, familiar, but not the source of the heady hyacinth-like perfume that pulled him deeper into the garden. Along the next curve of the path, the moonlight fell on a bank of tall flowers covered with whorls of white and pink blossoms. Their scent was so rich that its sweetness echoed on his tongue. He did not know their name, and he found their anonymity comforting.

As he stood, he sensed the presence of someone, or something. At the opposite end of a long bed of flowers, a figure emerged out of the darkness into a pool of moonlight. The figure turned slowly toward him, revealing a woman in a long hooded cloak that fell almost to the ground.

Her face came fully into the moonlight. He would have known her—the shape of her face, the contours of her cheeks—even if it had been pure dark. When her eyes met his, he felt trapped, paralyzed, as the body does at the end of dreams when not fully awake. He didn’t attempt to speak. She wasn’t real. Instead, he stood, fists clenched, his heart beating fast, waiting for her to disappear.

She seemed unsurprised to see him, as if she had been waiting for his arrival. In one hand, she held a cutting of the plant, its white blooms still open. She lifted the other hand slightly, palm up. To welcome him or ask for forgiveness, he didn’t know. She paused, watching his face. Then she stepped back into the darkness.

He knew not to follow.

In the pool of light, a white blossom lay on the ground.

Sophia Gardiner, Lady Wilmot, kept to the darkest parts of the path, cursing. He hadn’t recognized her, she consoled herself. He couldn’t have. It had been too long, and she was much changed. Her face had lost the winsome fullness of youth, her lips had thinned with worry and determination, and her eyes carried the sadness of one who had long lived with death. But what if she were wrong?

At the end of the park, her hands struggled against the latch of the iron gate, tearing the skin at her knuckles. She ignored the pain, looking over her shoulder into the darkness. Only darkness. The gate pulled free, but she forced herself to close it quietly behind her, lest the sound betray her escape.

Past the gate, she needed only to reach the corner, then a turn would protect her from sight. His sight.

She’d risked the night to see the Nottingham Catchfly—Silene nutans, she could hear her father correcting. They only flowered for three nights. That afternoon, her son Ian had brought her a spent white flower, asking her to name it. And she had been unable to resist the pull to smell its richness once more. The last time, she had been seven, her mother still alive. On each night of its blossoming, she, her mother, and her father had walked through the fields, until they reached the spot where the scent overwhelmed their senses. Afterward, they celebrated with savory biscuits flavored with rosemary and candied lemon peel.

She turned the corner and leaned back against the cold wall, listening for the sound of his pursuit. But she heard only the hard beat of her heart.

She had planned to propagate the cutting in her hothouse, then show Ian how the burgeoning buds heralded which nights the plant would bloom. She’d hoped the pleasure of the flowers blooming white and sweet might dispel some of the lingering sadness in Ian’s serious blue eyes.

Had she imagined Aidan would find her in the park, at that hour, she would have stayed home for another year, or twelve. It wasn’t solely for mourning that she hadn’t ventured out; no, she’d stayed home to avoid the risk of seeing him again. Now her efforts had gone for naught, and at what cost? What would he do now that he knew she was back in London? She pulled away from the wall and walked swiftly to the alley that led to the mews behind her home. Before she turned in, she looked back. The street was empty.

When she had seen him standing at the end of the row, she’d known immediately who he was. She felt the pull of his presence, tight in the depths of her stomach. How could she not know him? Memories of his lips, warm on her neck and shoulders, had never left her. Even on her wedding day, her thoughts had turned to him.

She wiped unbidden tears with the back of her hand, then cursed herself for crying. But he’d been so beautiful, even with his face in the half-light, the shadows forming smooth planes below his cheekbones.

He hadn’t spoken, only looked at her as if he saw through her. She wondered what he had seen in that long gaze: her guilt? her fears? her desire? But as he’d watched her, she’d known—if she hadn’t known before—that she would never be free of loving him.

She would never risk visiting the night-blooming flowers again. Even though she’d promised Tom, she wasn’t yet ready to share her secrets with Aidan.

Perkins dug in his shovel, loosening the dirt of the garden beds. “M’lady, which plants were ye wanting as a border for this bed? There’s plenty of boxwood.”

Sophia looked from her plans to the plants from her country estate. “I want box as a border for the outer beds, but for these inner beds, I want a different texture. Lavender, perhaps?”

Perkins wiped his brow with the back of his hat, leaving a smudge of dirt on one temple. “We’ve enough for this bed, and there’s more at the manor house.” At the wagon, he chose similarly sized lavenders to form an even border.

Turning her attention back to her plans, Sophia saw the torn skin at her knuckles. She bent her fingers, the dull ache a reminder of her recklessness. There would be no consequences, she promised herself for the twentieth time. Aidan had not followed. He had not known her.

For more than a year, she’d been plagued by a sense of foreboding. She had left London a bride not yet twenty and returned a widow not yet thirty. Buffeted by the salt wind as the ship approached the white cliffs of Dover, she’d knelt beside her watchful young son, drawing his shoulders into her side and whispering comfortingly, “This is England, Ian. This is home.” But she knew it wasn’t true. After the deaths of her parents, she’d never had a true home in England, only the unstable generosity of her father’s relatives. And the loss of Tom’s protective presence left her feeling hollow along her spine.

But if England were not her home, she could make it a home for Ian, and home for both of them meant a garden. Each night after she kissed her dark-haired boy good night, she sat at her easel, drawing and redrawing the garden beds, then watercoloring each one to see how the plants would complement one another. Her estate manager, Seth Somerville, had sent so many plants from the estate that she wondered if he had been pleased to see her setting aside her mourning.

Perkins, a laughing Cotswold plantsman with a gift for “growin things,” returned from the wagon and began setting the lavender in the bed.

Sophia watched him work. She loved the planting. Seeing the flat paper of her watercolor designs transform into the depth and height of the plants gave her a sense of purpose. For too long she had felt like a tree struck by lightning, not dead, but never putting out new growth. She was afraid of disturbing that precarious stability, but perhaps—despite her encounter with Aidan in the park—she would find a way to take root and thrive here.

“What goes inside the lavender, m’lady?” Perkins interrupted her reverie, his wheelbarrow empty. He stood, tucking the spade into the side of his belt.

“My son asked for forget-me-nots, petunias, and marigolds . . . all in a jumble together.” She tucked a lock of walnut-brown hair back under the confines of her bonnet. “They were my husband’s favorites, and tomorrow is the anniversary of his death. I’d like to have this bed ready as a remembrance.”

“Happy plants, those are. I will have the bed planted this afternoon.” Perkins pushed his wheelbarrow back to the wagon.

As she watched Perkins move the marigolds, already blooming, into the wheelbarrow, Sophia recalled a long-forgotten memory. Ian, holding out marigolds in both hands, toddled toward her, with Tom, ever watchful, walking closely behind. Tom’s eyes had met hers, and they had both smiled. Struck by the sweetness and the sorrow of the memory, she felt her throat tighten.

Perkins returned from the wagon, then looked past her toward the house. “Mr. Dodsley needs your attention, my lady.”

Sophia turned to find her butler, all smooth propriety, approaching with a small silver tray. “M’lady, a note from Mr. Aldine. His messenger is waiting for your reply.”

She recognized the plain, concise hand of her solicitor as she took the note, a single sheet folded to make its own envelope.

“Also,” Dodsley continued, “Mr. Murray has sent another packet. I took the liberty of placing it on your desk in the library.”

“Thank you, Dodsley. I’ll write my reply in my dressing room and ring when I am finished.” Sophia took her leave from Perkins, who was setting Ian’s garden into an orderly chaos. As she walked back to the house, she broke the seal and unfolded the note.

In the warm sunlight of the garden, Sophia felt the chill of foreboding return.

Sophia stood in front of her wardrobe, trying to choose a dress for her afternoon meeting with her solicitor. She had already removed her garden frock and apron, and washed her arms, chest, hands, and face in the basin. Now she stood in her chemise, staring at her choices. It should be easy: one black mourning dress looks much like another. What, she wondered, did one wear to accompany a sense of impending disaster?

In a way, the problem of the dresses was rather funny. There were only three, and, by now, the ever-observant Aldine had probably catalogued her entire afternoon wardrobe in one of his precisely ruled notebooks. The only thing he had never seen her in was her chemise. There, that’s a decision: wear your undergarments downstairs and see if Aldine blinks or just takes out his notebook and makes another entry.

With a sigh, she chose the unassuming black silk that buttoned from the bodice to the floor. The practical choice, she thought. It required no help from her maid, allowing Sally to remain in the nursery with Ian. As Sophia pulled the dress on, she felt the wear on its covered buttons. It was no longer a dress even a widow in mourning would wear, but the thought of venturing out, of buying new clothes, overwhelmed her.

To calm her nerves, she stood at the open doors of her balcony. Below her, the pale green grass darkened into deep shadows below the oaks, yews, and alders, and past her yard, several houses over, a statue of Flora, goddess of flowers, stood on top of a conservatory of iron and glass. Hers had become a circumscribed life, and one Tom would not praise. The house, the garden, the park with Ian, the vista from her window, they had become the whole of her world. It was a stark contrast to their life in Italy, filled with laughter and sparkling conversation. But Tom’s death had stolen her ability to talk brightly about nothings with near strangers. She had no idea how to broaden her circles, or even if she wished to. Just as with the dress, she was caught in limbo. She didn’t know how to change, or even if she could.

She touched the small key worn on a ribbon around her neck, a reminder of her unfulfilled promises to Tom that weighed increasingly heavy on her heart. Breathing in slowly, she turned and left her room.

As she walked down the back staircase to the library, she tried to imagine the reason for Aldine’s visit. The newspapers were filled with parliamentary debates on the stability of the Bank of England and its monetary policies, alongside stories of how vast family fortunes had been lost in a single day to volatile investments.

What if their money were gone?

The idea knocked the breath from her chest. She pressed her hand against the cool plaster wall. Would she lose the house and the estate? The London house was her refuge, Tom’s gift, allowing her to live in town rather than on his country estate, with her uncle and his prim wife for neighbors. But if it were a choice, she’d keep the estate. It was Ian’s future.

But both? What if there were nothing left? To be reliant on the narrow kindness of relatives was something she’d sworn she would never do again. But for Ian, she would reconcile with the Devil . . . or her brother Phineas. She preferred the Devil.

The image of Aidan standing in moonlight rose before her. She shook it off. She would do what she had to do. She always had.

If the problem weren’t their finances, then had someone learned their secret? But why take the information to Aldine, and not to her? To know, they would have to have the papers....

She had to know. She entered the library and pulled the key from beneath her chemise. Kneeling behind the partner desk she had shared with Tom, she pressed a latch hidden in the elaborately carved paneling. A panel moved to the side, revealing the door to a hidden compartment. She unlocked the door, holding her breath. The papers—and the hair she had placed over them—appeared untouched.

Suddenly tired to her bones, Sophia spoke to Tom’s portrait, hanging above the fireplace, “You promised me all would be well. But after last night . . . after seeing him . . . I don’t know how it can be.”

When her solicitor arrived, he handed her a letter in Tom’s hand, and she found that she had been completely wrong about how bad the possibilities could be. The truth was much, much worse.

Aidan stepped from his bath and rubbed a towel over his chest and upper arms.

“You’d enjoy rake’s hours more if you spent them on the town, your grace.” Barlow smiled at Aidan’s scowl. “I’m sure Cook would be delighted to concoct another sleeping posset. She says she knows what went wrong last time. Her newest recipe, she promises, will have you sleeping like a condemned man.”

“If I risk Cook’s remedies, I will be a condemned man. I prefer to lie awake until morning, then sleep until noon. I find it less damaging to my bowels than Cook’s remedies.”

“I think, your grace, you have simply lost your nerve.” Barlow chuckled.

Aidan threw the towel at the back of Barlow’s head. But his old sergeant turned and caught it. “You won’t be catching me out,” Barlow said. “I’ve been wise to your ways since you convinced me that the adjutant general’s daughter fancied me.”

“I thought your midnight serenade at her window quite affecting.” Aidan laughed. “I only wish the musicians had shown more talent.”

“As I remember, your grace, you hired the musicians. Promised me they were the best in town.” Barlow folded the towel in two brisk motions.

“But I didn’t say which town. The madam of the brothel assured me she hired only the highest caliber of musician.” Aidan smiled. “But I think you more than repaid me with the frog in my pack.”

“I still feel for that frog. I never expected you to carry him croaking for five miles,” Barlow said as he selected clothes from the wardrobe.

“It would hardly have been fair to leave him to find his own way to a good pond.” Aidan watched Barlow’s choices. “Am I entertaining visitors?”

“A Mr. H. W. Aldine.” Stout and sturdy, Barlow had the face and the manner of a man other men trusted. Given fifteen minutes, Barlow could take any recruit’s full measure, knowing his hopes, dreams, fears, and most important, whether he cheated at cards. When Aidan left the regiment, he had taken Barlow with him, and on their missions, Barlow’s instincts had more than once saved their lives.

“How does he look?”

“Like a solicitor.”

“Not another creditor trying to recover my brother Aaron’s debts?” Aidan asked as he pulled on his trousers, shrugged into the suspenders, and buttoned the fall front on each side.

“No, your grace. Too careful with words. And he carries a portfolio of papers.... I placed his card on your desk.” Barlow helped Aidan into his shirt.

“So if he is a creditor, he has the good sense to pretend to be something else.” Aidan allowed Barlow to tie his cravat. “Well, show the solicitor into my study. I’ll be down presently.”

Aidan walked into his study five minutes later, having run a comb through his wet, unruly hair. His dress was casual enough to signal a lack of concern, even contempt for the business at hand. Creditors were like wolves. Any sign of weakness translated into deep losses for the ducal estate. Five minutes of polite attention could lead to months of negotiation. No, Aidan had learned quickly after his eldest brother’s and then his father’s deaths: a dismissive nonchalance produced the best resolutions.

A stolid man, Aldine stood behind one of the more comfortable chairs, his worn leather portfolio open in the seat before him. Aidan sized up the solicitor as he had a row of army recruits or his contacts in the more perilous world of intelligence gathering. Barlow was right: this man was no creditor. Inked at the fingers, but meticulous in his clothing, Aldine held himself with a grace that belied his sturdy frame. A man to have beside you in a fight, Aidan realized. He reconsidered Aldine’s fingers: a man who wished to be underestimated. How, he wondered, would Aldine respond to a frog in his portfolio?

“Well, Mr. Aldine, what business is so urgent that you must come without warning?” Aidan used the brisk tone he found most effective at limiting unwanted interactions.

The solicitor looked from Aidan to his study. Aidan watched with interested satisfaction, knowing the room revealed little. The furniture was well-appointed, the objets d’art fine, but not extravagant. The pieces revealed no particular preference as to period or style: an ancient Grecian urn on a carved mahogany pedestal stood before a contemporary painting by a little-known artist. Aidan wondered whether Aldine saw a rake, unkempt from a night of carousing, or the former officer known for his ruthless detachment. The men’s eyes met, both having taken the other’s measure.

The solicitor folded his hands behind his back. “I come on behalf of Thomas Gardiner, the late Lord Wilmot. I’m to deliver a letter his lordship wrote you shortly before his death. If you agree to the proposition he outlines, I have brought papers for your signature.”

At Tom’s name, Aidan stiffened with complicated emotions: fondness, regret, anger, betrayal. “Wilmot has been dead a year, yet the delivery of these papers is urgent?”

“Lord Wilmot was very specific. Your letter—and one to his widow—were to be delivered within a day of the first anniversary of his death.”

“Then it is convenient I am in town.” Aidan leaned against the edge of his desk.

Aldine held out a letter, its seal unbroken. “His lordship instructed I am to remain while you read.”

Aidan nodded acquiescence, and Aldine began laying out papers on the desk.

Tom’s handwriting, though still legible, had grown less controlled.

Had Aidan been alone, he would have cursed out loud. Tom’s letter was unwelcome, as unwelcome as Aidan’s father’s summons five years ago to return from the wars to care for the ducal estates.

Aidan turned to the guardianship papers, noting several contradictions between them and Tom’s letter. “Let me make sure that I understand. Wilmot’s son is to live with me part of the year?”

“If you wish. My firm disperses funds for the boy’s maintenance, supported by the approval of both guardians, or one guardian and our firm.”

Aidan raised one eyebrow. “What is the rationale there?”

“If one guardian is unavailable or if you and Lady Wilmot cannot agree, the firm adjudicates on the child’s behalf.” Aldine offered a long pause. “It is a right we prefer not to exercise.”

“Ah, money is tied up in this arrangement.” Aidan leaned forward toward Aldine. “Did Wilmot believe his wife would run through the funds?”

“No. His lordship valued his wife’s judgment. She’s an able manager.”

“He valued her judgment, but removed the boy’s estate from her control?” Aidan let his voice convey disbelief.

“No, the estate remains under her ladyship’s control until the boy’s majority. This guardianship administers a trust for the boy’s maintenance. Wilmot wished to provide the boy with a male mentor, but you can refuse the guardianship.” Aldine pulled another document from his portfolio. “Your signature on this makes Lady Wilmot sole guardian.”

“So it’s me or no male guardian.” Suddenly, Aidan remembered Tom as a boy, playing King Arthur and his knights with Aidan and his brothers. He cursed inwardly: Tom had known honor would not allow Aidan to refuse. “Then I will accept.”

Aldine returned the refusal to his portfolio. “My clerk can witness your signature, unless you prefer someone of your household.”

Aidan rang the bell. “I always prefer someone of my household.”

Aldine moved Aidan’s copy of the legal papers to the side and produced the official contract, a large piece of vellum, carefully lettered, with six signatures and seals already in place. Three signatures dated from shortly after Wilmot’s marriage: Wilmot’s own, large, flourished, and confident, and those of two witnesses. Wilmot’s seal—a dragon’s head—drew Aidan’s attention. Something tugged at his memory, but wouldn’t come clear. Lady Wilmot’s hand was firm, but restrained; her witness, an Italian with a neat Continental script. Aidan read over the official document to ensure it was consistent with his copy.

When Barlow arrived, Aidan signed in his best, most official hand, adding flourishes to the tail of the S in Somerville, the curve of the D in Duke, and the F in Forster to mirror those in the ducal seal. An expansive signature to suggest full and willing consent. Barlow signed in a competent school hand, then slipped from the room.

“While the ink dries, have you any questions?” Aldine offered.

“I would like a sense of Wilmot’s intentions beyond this.” Aidan waved his hand over the documents. “I leave London in three weeks. May I take the boy with me to my estate?”

“The guardianship papers stipulate you may, but it might be wise to delay exercising that provision. Though his lordship established the guardianship a decade ago, her ladyship appeared surprised it had been called into effect.”

“What you do mean?” Aidan knew Tom never kept secrets without a reason.

“Lord Wilmot sent the instructions related to the guardianship in three letters, to me, to you, and to her ladyship. All were folded together in a cover addressed to my firm, signed and sealed by Lord Wilmot and carried to England by her ladyship.” Aldine tested the edge of the ink for dryness. “It seemed rather like the scene in Hamlet where Rosencrantz and Guildenstern act as couriers of the papers that lead to their executions.”

“An interest in drama, Aldine?” Aidan quizzed.

“A student of human nature, your grace.” Aldine folded the contract until it formed a tall narrow book with a title already carefully lettered on its spine.

“Why do you think her ladyship was unaware of the guardianship?” Aidan asked, interested in Aldine’s observations.

“Her ladyship rarely shows emotion. But her shoulders stiffened when she read the letter.”

“Then her ladyship is unhappy with this ‘partnership’?” Aidan replied, pleased at the news.

The solicitor returned the documents to his portfolio. “I simply report her response to the letter.” Aldine withdrew a slip of paper and held it out. “Lord Wilmot purchased a house for her ladyship quite close to your own. If you do not wish to meet at her ladyship’s, my office is also available.”

Aidan looked at the address—Queen Anne Street, just around the corner. Near the park. The implications settled slowly. Aidan could likely look out his bedroom window and see her yard. “No, I will call on her.”

“Those copies are yours.” Aldine indicated the papers remaining on Aidan’s desk.

Aidan extended his hand in parting. The solicitor’s handshake was firm and confident.

Aidan waited until the solicitor reached the door. “Wilmot’s letter claims that her ladyship is devoted to the boy. Is that correct? Women in the ton often find children merely an obligation to be fulfilled.”

Aldine paused. “Then her ladyship is unusual. Observe the mother and the son together to determine the depth of her ladyship’s affection for her child.”

“Why do you say that?”

“You will charge me once more with a fondness for drama.” Aldine placed his hand on the doorknob.

“I’ll refr. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...