The light looks yellow and sickly as the day fades. Shadows reach across the scrubby, open ground and the wind across the common is sharp on my face. The rain falls quietly, as it has all day.

I pick my way around the puddles and the soft wet mud in the ruts. I’ve been out in the open all afternoon, doing my bit, helping with the search. The toes of my boots are stained with dark, watery half-moons. My nose runs in the cold and I reach in my pocket for a tissue.

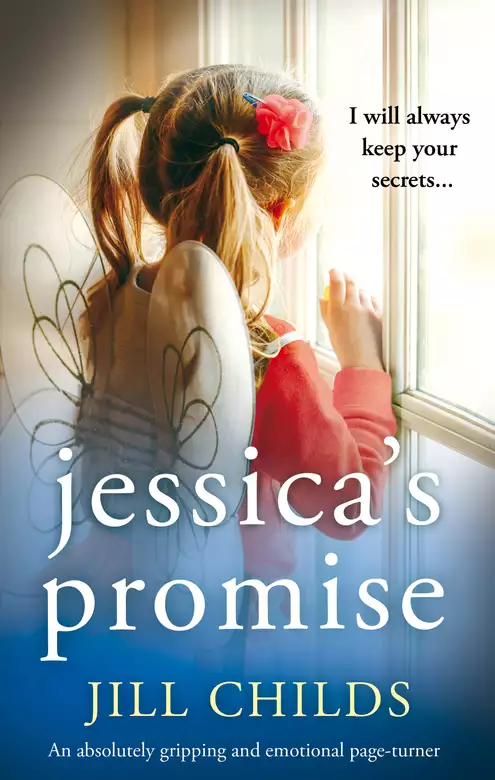

My hood makes a warm cave for my head and the fabric down the sides rustles against my ears. Everyone keeps talking about her, about little Jessica. Sharing memories, shyly, trying to stay positive as the police told us, but anxious, too. I can almost hear her giggling. If she were really here, she’d have her wellies on, the bright pink ones, and she’d run ahead, then back, a fireball of energy, nosing out puddles and runnels and patches of standing water where she could jump up and down, flat-footed, laughing, sending dirty arrows of wetness flying in all directions. And despite the waterproof trousers, the wellies, she’d have sodden socks in a heartbeat.

I stop and stare across the wiry grass and bushes, fingered now by wispy fog. The noise in my ears recedes until all I can hear is the thump of my own blood. A heartbeat.

A car passes on the top road, slowing as the driver looks at the fluttering tape stretched between stubby poles. The sharp sound of a whistle breaks through the stillness. An instruction. Someone may have found something. A possible lead.

I twist back to look at the ragged line of volunteers, some cheery and determined, others silent and sombre. They’re distant now. Police officers, marked out by their hi-vis vests, are peppered between the locals as they all process slowly forward. They stir the grass with metal rods, endlessly searching.

I pull my coat closer around my body, stick my hands deep in my pockets and set off again, taking the path down towards the river. I quicken my pace. I need a break from it all. I need to get away, to walk off some tension. I’m jittery and I’m frightened of behaving oddly, of letting something slip. Of being noticed. They treat me carefully and with kindness. They think it’s grief, warping me. But it isn’t. It’s guilt.

I never thought this would happen. Never in my life. All I wanted was to teach her a lesson. She deserved it. It just went too far, that’s all. I just started something I couldn’t stop.

August has been a scorcher. I’m teaching Harry how to fold up the paddling pool, taking turns to lie on the plastic and roll back and forth, trying to make ourselves broad and heavy to squeeze out the last gasps of air, Harry’s small feet bare and muddy from the churn of spilled water, when the new patio doors on the other side of the fence squeak open and voices tumble out into the garden there.

‘Look, Jessica. Isn’t it lovely?’ A woman’s voice, gushing and rather too quick. ‘See? Our own garden.’

Harry and I look at each other. Since Mrs Matthews died, no one’s lived next-door. Just months of builders, banging and drilling and throwing up dust. We’d made a game of imagining who might move in. Trolls or witches, or maybe a hero with superpowers.

In a flash Harry is on his feet. He runs to climb up onto the edge of the rockery wall and stick his head up over the fence to look.

‘Hello.’ A man’s voice. ‘What’s your name?’

Harry ducks down, startled. He’s young enough to think he can stare at someone without being seen.

I force myself to climb up beside him. ‘Hello. Sorry. We heard voices.’

There are three of them in the garden. The man is about forty, strong shoulders and neatly pressed clothes that look expensive. He smiles but his eyes are cool as they look me over.

The woman beside him is a little younger, mid-thirties perhaps, but also carefully dressed in tailored slacks and a crisp blouse, unbuttoned low enough to show cleavage. She’s attractive, with a sharp haircut, but she’d be prettier, to my mind, with less make-up. Her mouth is bright red and her eyebrows plucked almost to extinction. A cardigan hangs around her shoulders, the sleeves loosely tied at her neck. She wears sandals, and even through the roughly cut grass her toenails shine the same bright red as her mouth. No better than she ought to be, as my mum would say.

They don’t respond at first. They seem to be deciding what to make of me and I feel embarrassed, as they hesitate, about my mop of curly hair which needs a cut, and my face, bare of make-up and lined by so many years in the open air. The truth is, I’m a bit awkward with people. Not with kiddies – just grown-ups.

The man collects himself and steps forward, reaches up to the top of the fence and tries to shake my hand over the top panel.

‘Craig,’ he says. ‘Craig Fox.’ He nods to the woman. ‘And this is Teresa.’

‘Angela Dodd.’ The words sound odd in my mouth. I’ve never been one for formalities. ‘But everyone calls me Angie.’

The third person in the garden, who’s been running circuits through most of this, exploring the pocket-handkerchief garden with its mud patch waiting to be planted, and poorly tended square of lawn, finally stops and looks up.

‘And that’s Jessica,’ says the woman.

Jessica’s a sweetheart, I see that at once. Dark brown hair, cut in a bob, big brown eyes and a solemn, thoughtful expression. Just like my Susie at that age. Bright as a button and gorgeous with it.

Harry, who’s popped up next to me again, jiggling around on our bit of shared wall, says: ‘I’m Harry. I’m four and a half. I’m going to start big school. How old are you?’

Jessica considers him in silence.

‘You’re three, aren’t you, Jess?’ The woman steps closer to the child and messes her hair until she ducks away from her hand. I don’t blame her. Children hate that, they’re not dogs. The woman must catch something in my expression. She looks embarrassed and turns away, back towards the house. ‘And that’s Fran.’

I follow her gaze. They’ve built out, adding an extension with smart wall-to-ceiling glass doors and fancy lights. I can’t see far inside – the closed panels reflect the sunny garden back to itself – but what I can glimpse is bright and modern. Very different from Mrs Matthews’ dingy old kitchen and peeling back door.

Something low stirs and catches my eye and I look more closely. There’s a seated, slightly hunched mound of person there in the open doorway. She’s in dark, baggy clothes with outsized headphones covering her ears. Her expression is dreamy, as if she’s far away in a world of her own music.

The woman’s voice is shiny with tension. ‘She’ll be starting at really big school soon, won’t you, Fran?’

No response. Harry, bored, jumps down and goes back to the collapsed paddling pool.

‘Big job.’ I nod towards the house.

The woman looks away. She strikes me as a bit stuck up.

He smiles and says: ‘Bigger than we thought. But it always is, isn’t it, once the builders get going?’

I bet. That house hadn’t been touched since the ark. I went round there with my mother when I was a girl. The Matthews boys never bothered with me – they were that bit older – but Mrs Matthews and my mum liked a chat and she’d always give me a biscuit.

But that was a long time ago. And in recent years, after Mrs Matthews had the stroke, it became a real health hazard. I had to get a man out last year about the rats. Revolting. I used to hear them at night, gnawing and scuttling about in the dark cavities under the roof, hidden from sight on her side of the dividing wall. He found a few droppings in the attic and put down poison. But without getting at her side, there wasn’t much more he could do. She’d stopped answering the door by then.

Anyway, all through June and July, the builders filled and re-filled their skip outside. The skin and bones of that house, of her long life there, were torn out piece by piece and sent to the tip. Faded old carpets, stained plasterboard, rolls of lino from that old kitchen and the smashed-up units where she’d stashed her tins and packets, most of them rusted and out of date. Sad, but it needed sorting. And now, finally, the new people are here.

‘Well, good luck getting settled.’ I’d love to find out more, even have a nosy inside and see what they’ve done with the place, but now’s not the time. ‘Bye for now.’ I nod at the man, then add to little Jessica: ‘Come over and play sometime if your mummy doesn’t mind. I’ve lots of toys.’

She puts her head on one side like a bird and watches me as I climb down and disappear from sight.

The following two weeks are my last with Harry and we stay out a lot, having adventures while we can.

In the evenings, I sit at the back door, feet bare and tingling, feeling the final warmth of summer on my face and drinking white wine. I keep a permanent stock of those big boxes of white. It’s good enough quality, not too dear and the supermarket delivers.

Next door, they clatter and bang until late and I imagine the work unpacking all those crates and boxes and getting straight in their shiny new house.

They keep the windows open, getting rid of the smell of new paint, I expect, and I hear more than I ought to. Craig’s voice, booming and jolly, calling them to meals or rounding them up to play some game, or get ready to go out.

Her voice is sharper. When she gets cross, her tone becomes hysterical, a martyring wail, as if the children are torturing her with their naughtiness. Most of it is aimed at the little one.

‘Why, Jessica? Why? What’s the matter with you? Just stop it. Why can’t you listen?’

No way to speak to little ones.

Once in a while, little Jessica screams back. Childish stuff, calling her mum stupid, saying she hates her, she won’t do whatever it is she’s asked. They all have tantrums at that age but, even so, it makes me sad, hearing them at it.

My head slackens and grows fuzzy as I sit there, drinking and listening and drinking a bit more and instead of feeling peaceful, I end up quite melancholy, thinking about families and all the shouting that goes on behind closed doors, all the children who grow up feeling they’re nothing more than a nuisance.

September comes and the weather turns colder and Harry moves on, starting school, and I put the heating on and that’s the end of sitting at the back door. Next door’s noises become muffled by closed windows and the walls between us, reduced to the echo of a banging door once in a while. I keep an eye out during the day but there isn’t much to watch.

Craig leaves early and comes home late. He has a silver car, a posh hatchback. Sometimes I glimpse Fran, hunched in a duffel coat, earphones on, heading off to her new school and, on occasion during the day, Jessica, buttoned up in a pretty red coat tripping along at her mummy’s side, holding her hand. I assume they’ve put the little mite in nursery. Shame. I’m looking for work, now Harry’s gone, and I had thought she might be just the ticket.

It’s about nine thirty, and I’m pottering in the kitchen doing the breakfast dishes, when the doorbell rings. I think it might be the postman although I’m not expecting anything. I open the door in my slippers.

Her perfume hits me first. Spicy. Then her smile, all teeth. Teresa looks glossy, even more so than usual.

‘I’m so sorry. Am I intruding?’

I think: Why did you ring on the doorbell if you don’t want to intrude? But I manage to shake my head, waiting to see what comes next. She’s all made up, her hair glamorous, wearing a skirt and a neat raincoat, one of those short Audrey Hepburn ones, belted around a thin waist. She has style, if you like that sort of thing. Her own front door, on the other side of the low railing that marks the boundary between the two sides of the path, stands open.

‘I know it’s a lot to ask’ – she hesitates, eyes on my face, reading me, as if she expects me to respond before I know what she’s on about – ‘but is there any chance you could mind Jessica for a bit? They’ve just rescheduled my meeting, you see, and I can’t say no, but Craig can’t get back in time.’

‘OK.’ I wonder what sort of meetings she has. I didn’t know she worked. ‘Now?’

Her face sags with relief. ‘Would you? I’d be so grateful.’ She looks past me into the hall. ‘Harry won’t mind?’

‘Harry’s at school. I’m not his mum. I’m a childminder. Yes, send Jessica over. No problem.’

She looks so pleased she might have hugged me if she were the type. Instead she just beams, nods, calls back across the path and, a moment later, Jessica appears. She’s clearly been hovering in the hall, already buttoned into her coat, a lumpy, stuffed bunny under her arm. She hesitates on the threshold, even as her mother tries to urge her forward towards me. Her eyes are wary.

‘Hello, Jessica.’ I crouch down to her level and smile. ‘I’m Angie. Who’s this?’

‘Rabbit.’

‘Well, Rabbit, I wonder if you’d like to come and play? And you can bring Jessica, too, if you like. Do you like biscuits?’

Teresa gives her a quick peck on the top of the head. ‘See you later, Jessica. Be a good girl.’

She disappears in a click of heels down the path, leaving Jessica looking mournfully after her. I wonder if she’s used to being dumped on strangers. I’d never have done that with my Susie, never. You wouldn’t hand your wallet to someone you hardly know, would you? Or your house keys? So why your little girl, the most precious thing you have?

I reach out a finger and stroke Rabbit’s head, gently, between her ears. The fur is worn.

‘I think we’re going to be friends,’ I tell Rabbit. Its glassy eyes are as sad as hers. ‘Come on in.’

I lead her through to the sitting room and open up the big toy cupboard. I’ve never yet met a child who can resist it. All my own toys are in here and a lot more besides, picked up over the years in jumble sales and charity shops. Bright colours and lots of variety. Plastic boxes of trains and cars. A small doll’s house. Stuffed toys. Crayons and stamps. Boxes of games. Tubs full of building bricks. Her eyes widen.

‘Now then, what sort of thing does he like?’

She hugs Rabbit closer. ‘She’s a girl.’

‘Of course she is.’ I smile to myself. ‘How about building her a house, then?’ I pull out some multi-coloured bricks. ‘Shall we have a go?’

I sit down on the floor beside her and we start to build. Within a few minutes, we’re at peace together, working quietly, side by side. No grown-up questions. No demands. Just leave them alone to be themselves, that’s my way of doing it. Keep it calm and friendly and a bit of respect and the world would be a happier place. What’s the rush anyway? She’ll take off her coat when she feels like it. Breakfast dishes can wait.

When Teresa comes back a few hours later, her mood is transformed. Perhaps it’s the sight of the two of us, snuggled up together on my battered old settee, reading stories. Or perhaps it’s just relief that her meeting went well. I make her a cup of tea and bring a tray through with a beaker of water for Jessica and a plate of plain biscuits.

‘I can’t thank you enough. Really.’

Teresa perches on the edge of a chair, her raincoat unbuttoned but still on.

I don’t know what to say so I just pour the tea and wait.

Finally, she asks: ‘How’s she been?’

‘Great.’ It’s true, Jessica’s no trouble – we understood each other from the start. Anyway, even if she were a handful, I never tell on a naughty child. That’s not how it works. ‘We’ve had fun, haven’t we, Jessica?’

Jessica takes a biscuit and goes back to the toys strewn across the floor.

Teresa prompts: ‘What do you say? Jessica? Thank you!’

We sit on for a minute or two. The clock on the mantelpiece has a loud tick and an old-fashioned mechanical purr when it hits half past – it was my mum’s, she always said it would see her out – and it whirrs now and makes Teresa jump. Her nerves are terrible.

‘I’m so grateful.’ Her words come out in a tumble. ‘I couldn’t think who to ask.’

I shrug. ‘It was good timing. Another half an hour and you might have missed me.’

Her eyes move from the clock along the mantelpiece to the photos framed there.

‘Is that your little girl?’

I nod. ‘Susie. Not so little now.’

There are two pictures. My very favourites. One when she was two and a half, coming down a slide, hair flying, eyes shining. Full of joy. The other was taken on her fifth birthday. We had a proper do. A party in the church hall and an entertainer. She’s dressed up in a sparkly dress with broad, stiff skirts. Usually my mum made Susie’s dresses but I got that one at a department store and it cost a fortune. I just couldn’t resist it and I’m glad I didn’t. Her hair was long in those days and tied up in ribbons. Pretty as a picture.

‘She’s a gynaecologist. Out in Australia.’

‘You must miss her.’

Stupid question. Of course I miss her, every hour of every day. I just shrug. ‘That’s what it’s all about, isn’t it? Love ’em and let ’em go.’

‘Have you been out there?’

‘Australia?’ I smile. ‘She keeps on at me to go but I’m not one for travelling. It’s too far.’ And too expensive.

‘Does she have children?’

‘Not yet.’ I pause, trying to imagine being a grandma. A little girl like Jessica. Even better, two or three. ‘Career comes first with Susie. You know how it is.’

She isn’t really listening, I can tell. She’s just making conversation while she checks out the room. Her eyes are sharp, prying, moving over the chaos of toys on the floor, the brick house built round Rabbit, the train track.

‘You’re certainly well set up.’

‘It’s my job. Looking after little ones.’ All I ever wanted to do, since I left school.

I know what she’s thinking; well, I can guess. It’s a shabby sitting room in an old house. A dodgy gas-fire in the hearth. Stained carpet. I’m not blind. It isn’t modern and shiny as hers must be now. But it’s comfy. It’s lived in. That’s what kiddies like. No need to be afraid here if you knock over your juice or get chocolate on the carpet. Never mind, it’ll wipe.

‘So difficult.’ She sighs to herself. ‘Isn’t it? Juggling work and children.’

I sense where she’s going and don’t answer. I don’t want to mess up.

‘I don’t suppose…’ She looks down at Jessica, who’s absorbed in catching the wooden fish in the fishing game, dangling the magnet to see how many can stick. The best reference for any minder is the sight of a happy child. ‘I mean, are you free at the moment? Would you be interested at all?’ She nods at Jessica.

I try to act nonchalant, as if I need to think it over. ‘Full-time?’

‘Well, yes. Ideally. I’m taking on a salon, you see. I’m in beauty. That’s what the meeting was about. And, well, it’s all moving rather quickly. They want me to start on Monday. The salon’s been without a manager for more than a month. You can imagine what a state it’s in. It’ll be a lot of hours. And the odd evening, too.’

I look down at Jessica, thinking. ‘What about your other daughter?’

‘Fran? Oh, she’s not mine.’ She speaks abruptly, then seems to realise how it sounds and flushes. ‘She’s Craig’s daughter. I am Jessica’s mum, you see, but Craig’s not her dad – he’s Fran’s. And I’m Fran’s step-mother. The wicked step-mother.’ She laughs and looks embarrassed. ‘It’s complicated.’

I just nod. ‘How old is she? Eleven?’

‘She’s just starting at secondary. She can walk there and back herself, it’s not far.’ She considers. ‘There might be after-school clubs. But I can’t see myself being back until at least six thirty. Later, some days.’

I narrow my eyes, getting the measure of her. ‘I’m a good cook. I’d do lunch for Jessica and tea for both of them. Healthy plain food. Cottage pie, Bolognese, that sort of thing.’ I look down at my hands, twisting the wedding ring. It looks too small. My fingers aren’t as slim as they used to be. ‘I like to keep things simple. You know, cash in hand.’ I pause, waiting to see how she reacts.

‘Of course.’ She gets it at once. No tax, no fuss, keep it between ourselves. ‘What sort of rate would you be looking for?’

‘Well, for two of them. And there’s the food.’ I hesitate. ‘Say, ten pounds an hour, all in?’

I can see the cogs turning as she does the calculations. She’s no fool. But she won’t find cheaper, not for two of them, sole charge. And she needs flexibility. What nursery will keep a little girl until seven o’clock at night? And literally next door.

She nods. ‘Let me have a chat to Craig, OK?’ Already she’s buttoning her coat, rearranging her legs to leave. She’s got what she came for. ‘Come on, Jessica. Home time.’

For a moment, after they’ve left and the house falls silent again, I feel a pang of regret. She agreed too easily. Maybe I could have pushed it to ten-fifty. Even eleven.

But then I walk back into the sitting room and see the floor alive with toys, the broken brick house so recently abandoned by Rabbit and the trains scattered across the rug and the fishing game too. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved